Samantha Box: “Caribbean Dreams: Constructions”

Samantha Box’s project Caribbean Dreams encompasses oneiric tableaus and lusciously illuminated still-lifes in which the notion of borders emerges as a profound and open-ended question. What are the boundaries within ourselves and the world we inhabit? And how does the transformative psychic power of crossing them shape the understanding of ourselves and others? Criptic and captivating, Box’s photographs brim with cues that lead us towards an enigmatic place that is undeniably real, yet impossible to define or capture definitively. What is the Caribbean? For Samantha there isn’t a straightforward answer to this question: “It doesn’t have a shape or form. It exists everywhere, appears everywhere.”

In this interview for Lenscratch, Samantha Box speaks to Vicente Isaías about her ongoing photographic journey exploring her diasporic identity and the multifaceted essence of the Caribbean.

Samantha Box is a Jamaican-born, Bronx-based photographer. She holds an MFA in Advanced Photographic Studies from the ICP-Bard College and a certificate in Photojournalism and Documentary Studies from the International Center of Photography. Her work has been exhibited, most notably, at the Houston Center of Photography, the DePaul Art Museum, Light Work, the Open Society Foundation and the ICP Museum, and is in the collection of the Museum of Fine Art Houston. Box has been an artist-in-residence at the Center of Photography at Woodstock, the Visual Studies Workshop and Light Work, and was a Bronx Museum AIM fellow. She has been awarded a NYFA/NYSCA Fellowship in Photography twice: in 2010 and in 2022, an En Foco Fellowship, and a Silver Eye Fellowship. She has been shortlisted for the Aperture Portfolio Prize, the Louis Roederer Discovery Award, and the Prix De La Photo Madame Figaro.

Follow Samantha Box on Instagram: @samantha.box

An interview with the artist follows.

Caribbean Dreams

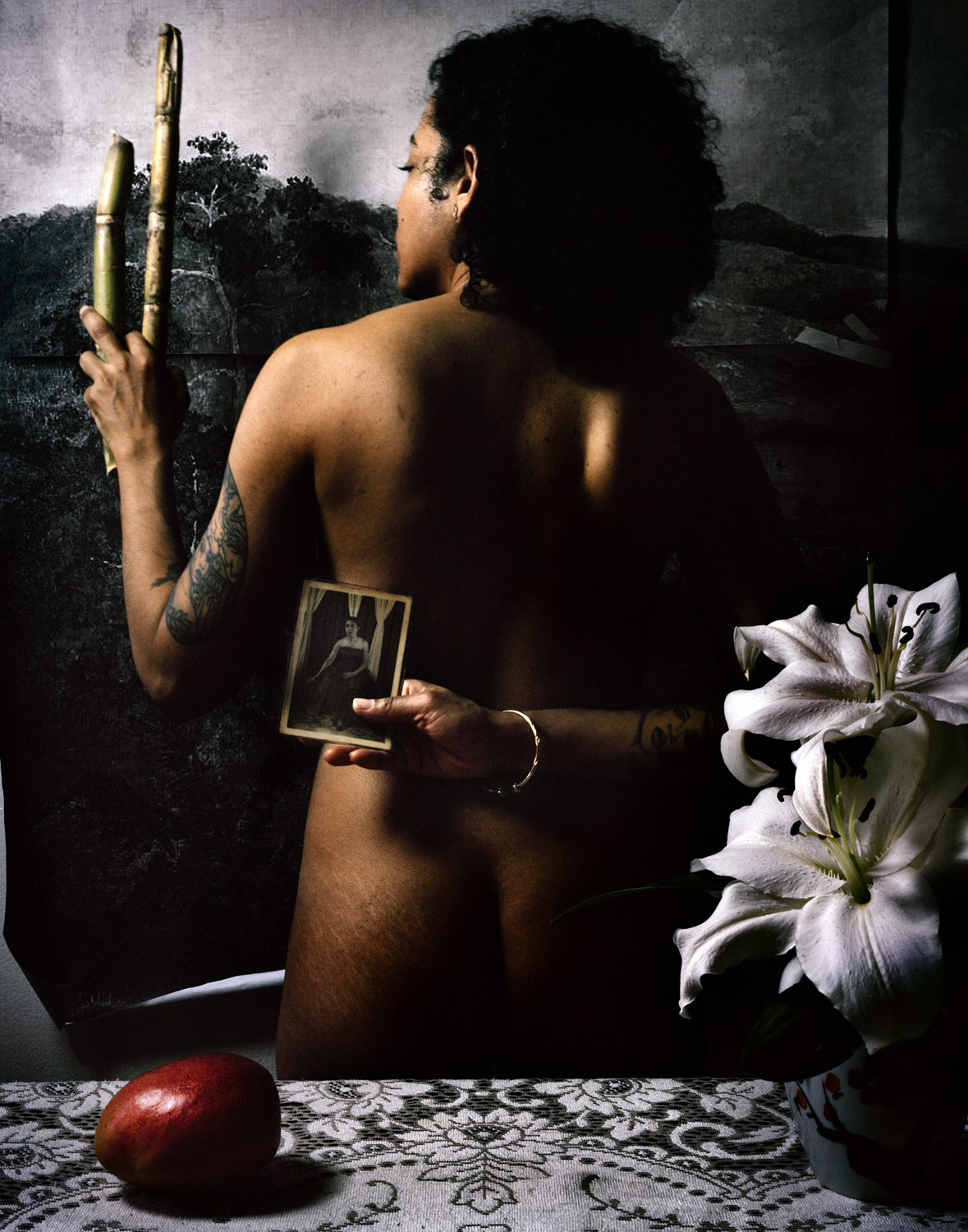

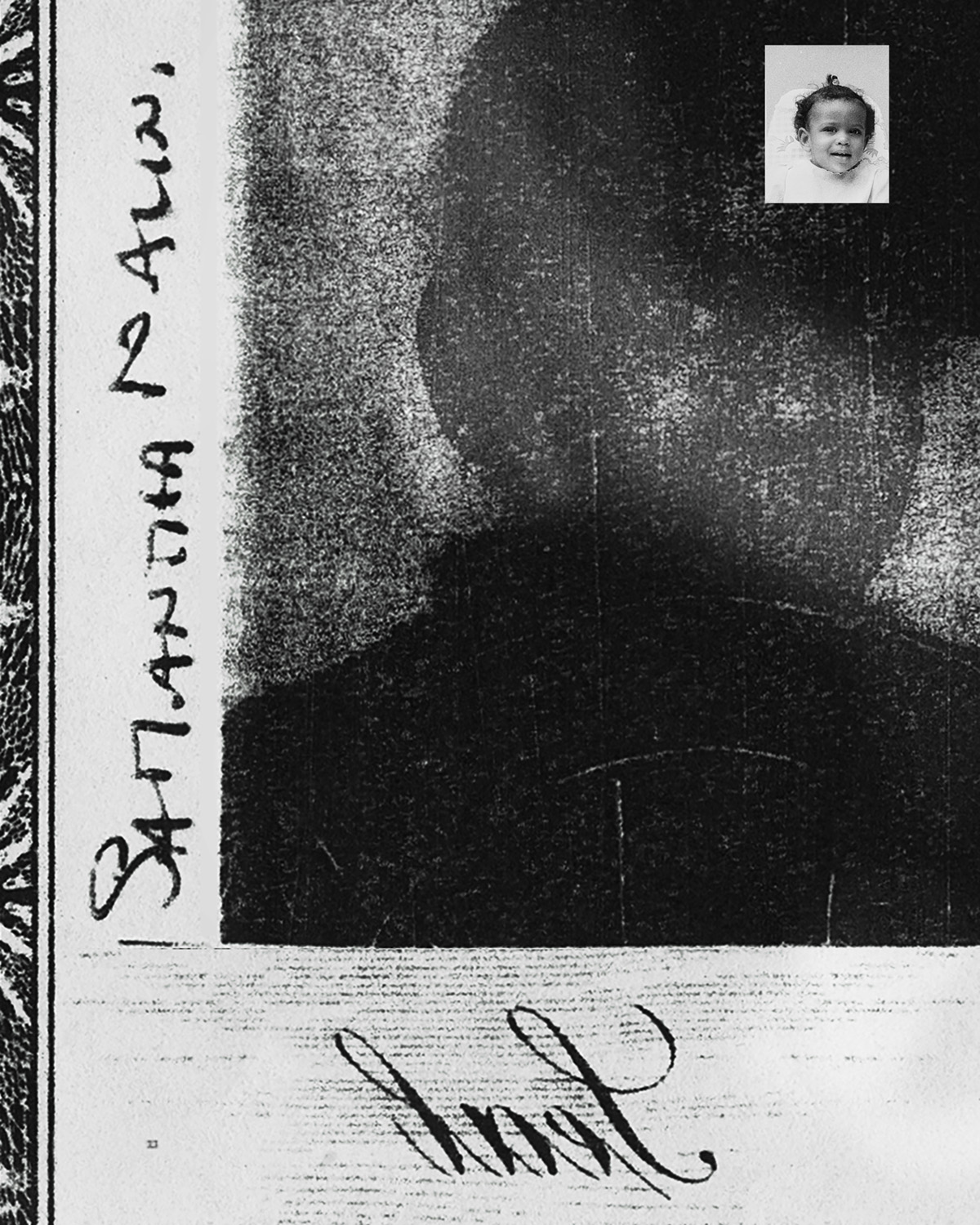

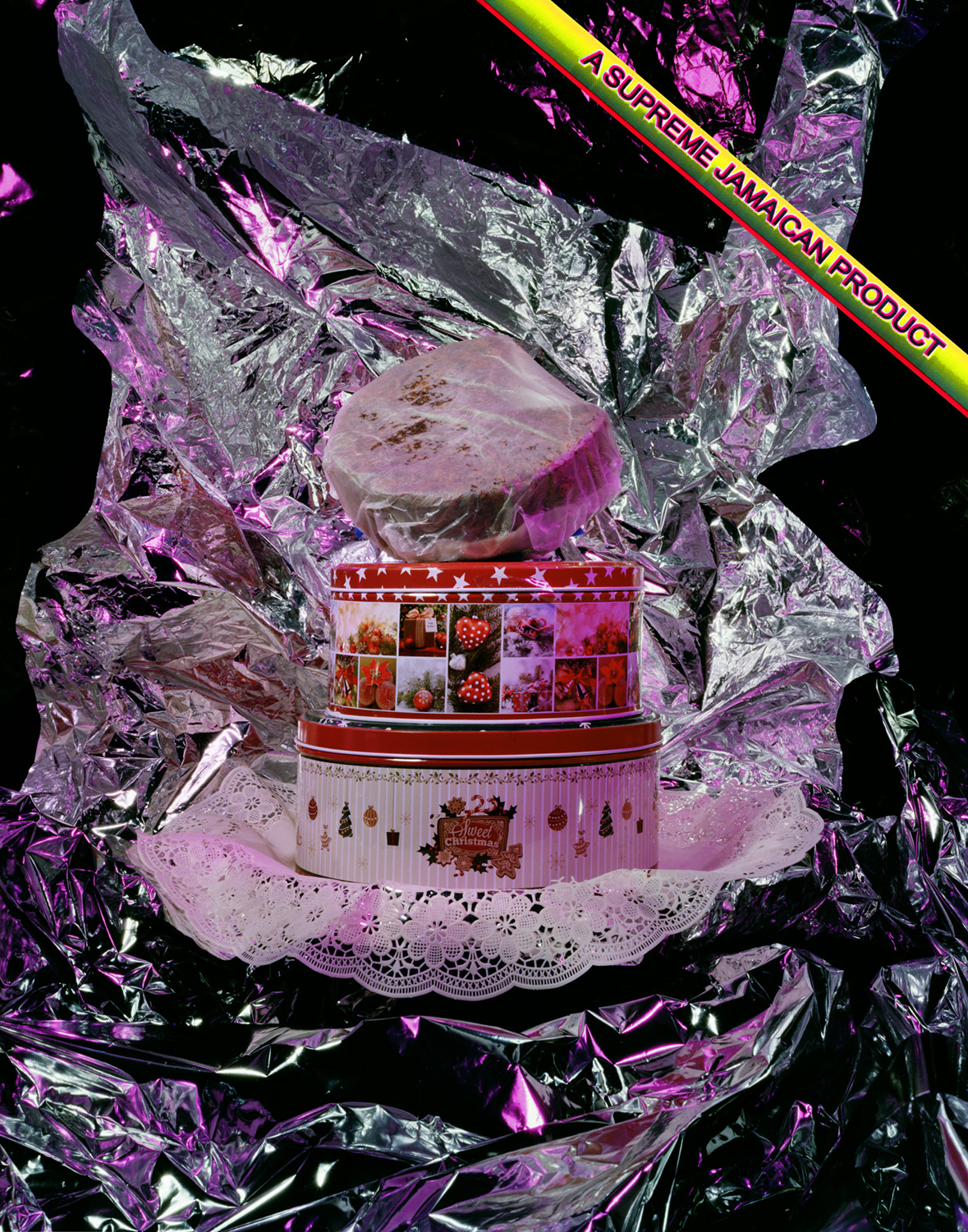

Caribbean Dreams is a montage: a place of slippage. Prompted by Caribbean cultural and political studies; familial and regional histories; and folklore and memory, Caribbean Dreams is an on-going series of complex studio tableaux and still-lifes of personal, familial and regionally referent objects, heirlooms, fruits, vegetables and plants, onto which family and vernacular images, fruit stickers, packaging and receipts are collaged. The constructed, experimental, and unpredictable compositions of Caribbean Dreams examine structures of exodus and diaspora, enclosing my – African and Indian, Jamaican and Trinidadian – histories and identities, proposing a notion of a self that resides within the multiplicity of Diaspora.

Throughout Constructions, forms restlessly reappear and transform – bodies multiply; fruit becomes seedlings, tablecloths become veils – in intricate, tense compositions. Formal portraits of seedlings, made under disorienting grow-light, prompt consideration of methods of survival of the transplanted, while produce stickers and packaging highlight global currents of commodification of culture, food and people. Exposure of the contours of the studio reveals its artifice, underscoring its use in creating the myth of a Caribbean paradise; within this break, the obscured body seizes autonomy. Contemporary family photographs disrupt the surface of a colonial image, proposing alternate narratives that refute calcified visual histories. A glitched baby picture rejects nostalgia for the “homeland,” while also declaring the arbitrariness of national identity, and of nation-state borders. Secondary narratives – in the form of receipts, produce stickers, and family photographs – disrupt the surface of the image, modulating and complicating the meaning of the base photograph. These constructed works are printed at size – up to 40×50 inches – immersing the viewer in the world-building happening in each image.

The unstable surfaces of these photographs present a series of questions: how does identity, culture and knowledge shift across borders? How can a photograph become more than a document, a definition? Each image works in synergy with each other, physically creating a diasporic space, akin to a portal towards complexity: of history, self, identity and narrative.

Vicente Cayuela: Samantha, thank you for joining me. Before talking in more detail about your series Caribbean Dreams, I’d like to know more about your background. You were born in Jamaica. What’s your fondest memory there?

Samantha Box: Hi Vicente, thank you for having me! For me, fond memories imply nostalgia for a thing, a place, or a person. I don’t really subscribe to nostalgia, and since I left when I was relatively young, 5 years old, I didn’t really have time to form “fond memories.” I don’t really have memories of what the experience of migrating from Jamaica was like, either. What I do have are intense sensory moments: flashes of color after my father moved a rock under which a family of snakes was hiding, the smell of burning things, the sharp light on a puddle of water after my classmates and I threw stones into it.

VC: I can feel that same sensory quality in your photographs: the color of the sunset on an analog light leak, the scents of fruit and sugar cane on your tabletops, all of which so strongly evoke a sense of place… Putting nostalgia aside and focusing instead on your experiences as a citizen of the Caribbean diaspora, what can you tell me about yourself and your art?

SB: My work on the whole is rooted in the “and/also” and rejects the “and/or.” I’ve never had, or subscribed to, the idea of the immigrant as “being caught between two worlds.” Places like NYC/Central NJ are diasporic spaces, where it is possible to create lives that transcend easy definitions of self, across identities. Living in the TriState area, growing up in Central NJ, and spending my adulthood in NYC, perhaps made it inevitable that my work would address the formation of identity in the flux of movement, across borders, or in the liminal spaces of society, among many other things. I’ve never not lived in places marked by movement, whether forced or chosen, within and into the boundaries of regions or nations, i.e. “The United States,” of people and cultures, and the afterlives of those moments.

VC: The liminal quality of your work and how your photographs challenge these “easy definitions” of self and place that you just mentioned is what captivated me about your pictures in the first place. White-sand beaches, sunset mimosas… The Caribbean often exists in the public imagination as a purified space devoid of its violent history as the initial point of colonization in the Americas.

SB: This is an ongoing question that I’m trying to work through in my practice. I am also trying to figure out how to address the aftermath of that initial point—of colonization, enslavement, and indenture, of the creation of the “modern world.” I hope that my use of artifice, and also the mashing—at times violently—of multiple cultural, historical, and political narratives into my images are working to address this. This is one of the key questions that drive my practice.

VC: Considering that romanticized representations of the Caribbean in mass media, art, and literature have also shaped how these places exist in the collective imagination, could you expand on how you use artifice in your sets to draw (or blur) the line between fiction and fact?

SB: The use of artifice started almost from the beginning of this work: the black and white backdrop that appears in multiple images is actually a very crappy blowup of a low-res photograph of a painting of colonial-era Trinidad. Showing that the background was made of overlapping and disjointed sections—and in later photos, held together by tape—was key in establishing that I was making work that was not about nostalgia or “returning home” or about a “retelling” of my experience.

Artifice pops up often on the edges of my work. It also pops up in the use of materials: sometimes that landscape is not made of “land” at all. It’s important that my work is understood to take place in a constructed zone of my personal experience, but also of the studio, and to show the boundaries/edges of that zone in order to call into question received visual ideas of the Caribbean, specifically of the British Caribbean, specifically of Black Jamaica and of South Asian/Indian Trinidad.

VC: I love how you’ve used that backdrop throughout the series. I notice that you also point to the fabrication of identity narratives by superimposing receipts, food stickers, and portraits of people. It is a very interesting way to ask: “What are the stories behind these people?”

SB: Exactly! Who are these people? Who alluded to the form of the fruits, stickers, the seedlings in Transplant Family Portrait? Who is “Cashier 1?” What are the stories of those whose bodies were/are brought here as commodities to work, to create wealth, modernity, our “Modern World”?

VC: Your photographs ask these questions in such a creative way, not only through still life but also self-portraiture. I’d like to know what role your body plays in these ideas of construction. Where do the limits of performance fall within your practice?

SB: When I make self-portraits, I sometimes need to step out of myself to get back into myself, if that makes sense. I think very carefully about how my body is positioned in the composition, the gaze, etc. That part can feel choreographed, as I need my body to match what’s in my mind, for the image.

Pulling back, my body, which stands at the intersection of multiple diasporas—within the Caribbean, of Black and South Asian diasporas, overlaid with an additional diasporic layer of “U.S. immigrant” that itself is loaded with the history of the Caribbean, its relationship to the US, and to the modern world. I do not perform that, it is apparent on my skin, in my hair, and on my body.

VC: Mirror #1 is one of my favorite self-portraits I have seen in a long time. Can you tell me more about it it?

SB: Mirror #1 was the first image that I made where I intentionally addressed where my work was taking place, that it was happening not in some mythical reconstruction of the Caribbean, but in my apartment in the Bronx. I wanted to address the self—me—existing in this other space, the space of diaspora; I wanted to show that shelf existing in space that was filled with “layers and layers.”

VC: I am really curious to know where you source the materials for your sets and if these places play a special role in your practice.

SB: All of the fruits and vegetables, with the exception of one photo, come from a green market that’s a block or two from where I live in the Bronx. This market is really important to me, but not in the sense of “acquiring things.” That to me would reflect the colonial acquisitiveness that permeates the history of colonized countries and our understanding of the cultures and biology of these places.

My question instead was, “As a diaspora citizen, what can I get my hands on where I live?” That became a kind of rule for the photographic experiment. It was crucial for me to source these materials from a single place because it’s a neighborhood that is in a constant state of flux.

A lot of the things I buy at the green market in the Bronx that I recognize as the Caribbean are not actually grown in the Caribbean. They may come from Mexico or other parts of the Americas. Many of these items that look like “beautiful things from the Caribbean” to the uninitiated are actually markers of empire, and can function much like the way that Turkish rugs, the tulips, or Chinese porcelain function in Dutch still life. These objects become symbols of empire and capitalism.

VC: This act of “re-definition” touches on such an important component of your work. The re-contextualization of these objects and people, of diasporic citizens, from one place to another, across borders, and then back to a place of artifice: the artist’s studio where another layer of complexity and dislocation is added.

SB: Right, these fruits and vegetables come into an American space and are encountered by me, a diaspora citizen, in this other space, and then I bring it into another space in my photography studio. Diasporic citizens are often asked to collapse their identities into more legible spaces. So the studio becomes a symbolic or conceptual space: a place where I can redefine myself, my landscapes, and everything else freely.

I am very interested in these shifting spaces of identity and demarcation of knowledge and culture. What I am really asking is, “How do identity, knowledge, bodies, and culture change when you cross a border?” And “How does this very arbitrary idea of a border change one’s perception of a place and also one’s own perception of oneself as a diaspora citizen?”

I often ask myself: What is it like to sit at the borders of many things? Why am I making this work? And I think to myself, if I do not do this work, then I will not know the answers to my own fundamental questions.

VC: That is fascinating! Circling back to this idea of constant flux, I noticed that before you became a photographer, you had a degree in biology. Where did this interest come from and what made you turn to photography?

SB: I went to Cornell for biology, but finished my degree at City College of NY, where I could also do photography classes. In the context of an immigrant family of scientists, the choice was, “you have to be a scientist. Or a doctor.” My parents are organic chemists who met at the University of the West Indies, in Jamaica when the country was destabilized by U.S. interference in the 1980s, mostly around anti-communism, as they were doing all throughout the World. Eventually, my father was sponsored by a pharmaceutical company based in NJ, and that’s how we came to the United States.

There are several reasons I turned to photography.For most of my life, I was interested in photography. But there were so many different reasons why I was discouraged from doing it. I would imagine that an artist who grew up in a family of artists and wanted to become a scientist would encounter the same kind of push-back. For a long time, my plan was to become a doctor. Then I asked myself what I wanted my life to look like and told myself that I wanted to spend my life doing something that interested me.

I took a photography class at the City College of New York with Shawn Walker. Immediately it was clear to me, “This is it, I am not going back.” I learned really quickly that you have to work hard to be a photographer. (laughs) But it was hard work that I wanted to do. With photography, I was constantly frustrated but I wanted to work through that frustration.

VC: Frustration can be a very powerful driving force. Not only can working on a set be frustrating at times, but it is also time-consuming and labor-intensive. How long does it take you to work on your photos?

SB: Oh my! (exhales) That is something I am only now really understanding. . . . It takes a lot longer to get work done now than it used to, when I was making documentary work with a digital camera. I am down to a cycle of one to two weeks where I set up first, start shooting, redo the set, and then continue shooting. I often think to myself, “Does this image need another layer?” I try to find a balance, you know? It’s entirely possible to say, “I’d like to tweak that little thing in the corner.” . . . It also took me a long time to figure out what a productive week even meant. When things get too out of control and I can not see where the picture is going, it becomes a weight around my neck more than an actual generative space. And if I am making a set and I break something down a couple of times and I am still not where it’s supposed to be, I definitely put it on the back burner until I can get back to it.

VC: It is so important to let the work breathe. In the end, I think all this frustration just speaks very highly of how intentional you are about everything that goes into making your tableaux.

SB: I totally agree, although I’ve been trying to give myself more time while also being mindful of that spiral that can happen where you get stuck. I’ve noticed that usually right when I get to the end of a box and just push it a little bit more, that’s when things start to happen.

VC: I can relate to that very well. The setup is not only where most of the physical labor occurs. It’s also where we spend most of our time mentally troubleshooting and finding solutions to the problems that arise when building something specifically for the camera. Don’t you think that each set brings its own challenges even if you have developed a system?

SB: Oh, totally! Tape is one of my favorite and the most crucial studio tools. I have tape in my bag with me at all times. (laughs) I am always asking questions. “I want this to happen. I want this thing to be here. But how do I get it to happen?” I’m constantly looking at things and I’ll just say: “Okay, I’m going to tape it.” Other times things are really just being held up by a pen. But sometimes, you are handling things that are precious to you. In my sets, there are things that I don’t want to break, things that were passed down to me. Ultimately, my practice—and all photography—really comes down to process, right? I teach in the same way. Practices are so fundamental.

VC: It all boils down to it, for sure, even if people roll their eyes at the word “process.” Samantha, thank you so much for this interview. It’s been a pleasure talking with you. However, I have a couple of last questions before we part ways. What do often you dream about?

SB: Thank you for having me, Vicente. I haven’t had a decent night’s sleep in a long time, but when I do sleep, many of my dreams take place in a defined place that does not exist outside of the dream—with defined landscapes and boundaries. When I started grad school, the place shifted, and I’m still figuring out where the hell I am.

VC: Utopian dreams, dystopian realities. In an anti-utopian era, how can we protect and keep intact our ability to dream, that is, to envision a better future?

SB: Well, the first step is to believe—to always believe—that there is another way/way of being besides the one that’s offered to us now, and the act of figuring out what that is, is what keeps the future alive. We don’t have to accept that how things are is the end of the story at all.

VC: If the Caribbean is a dream for many, what does it look like in your dreams?

SB: There isn’t a straightforward answer to this question. It doesn’t have a shape or form. It exists everywhere, appears everywhere.

Vicente Cayuela is a multimedia artist working at the intersection of staged photography, sculpture, and installation. His handcrafted photo-based artworks create colorful scenes of graphic overload and tongue-in-cheek cultural commentary inspired by juvenile aesthetics and material culture. His work has been exhibited in New England at the St. Botolph Club, the Griffin Museum of Photography, Abigail Ogilvy Gallery, and PhotoPlace Gallery, and published nationally and internationally. In 2022, he was awarded the Emerging Artist Award in Visual Arts from the St. Botolph Club Foundation, in Boston, MA, and was one of the seven winners of the 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize. Cayuela holds a BA in Studio Arts from Brandeis University, where he received the Susan Mae Green Award for Creativity in Photography and the Deborah Josepha Cohen ‘62 Memorial Award in Fine Arts. He has received numerous scholarships including a Wien International Scholarship from Brandeis University. More recently, he was among the six recipients of Atlanta Loves Photography’s 2023 Portfolio Review Equity Scholarships for lens-based BIPOC and/or LGBTQIA+ artists.

Follow Vicente on Instagram: @vicente.cayuela.art

Website: www.vicentecayuela.com

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025

-

KELIY ANDERSON-STALEY: Wilderness No longer at the Edge of ThingsNovember 19th, 2025

-

Jackie Mulder: Thought TrailsNovember 18th, 2025