Photographers on Photographers: Alice Fall in Conversation with Laura Steele

I met Laura Steele while studying photography at Bard College. Her steadiness, intelligence, wit, and engagement with the world is grounding and immediately magnetic. Laura’s constant reminder to me, both inside and out of school, has been to trust my vision and intuition. I’m thankful for her for bringing me back to myself, again and again. We’ve had many conversations hovering over a table stacked with prints, pulling at threads, listening to each other, and pushing each other. This relationship has been such a valuable intersection of friendship, mentorship, and collaboration. Here’s a transcription of one of our conversations from early June 2023. We took a walk and dove into the tensions of boxing in your practice, the balance of collaboration, and the importance of nourishing an artistic practice that prioritizes active listening.

Laura Steele

b. 1975.

Fractured & Whole.

she/they.

Artist.

Educator.

Mother.

Partner.

Friend.

Follow Laura Steele on Instagram: @steele_photoworks

Alice Fall: I’ve spent the past few days looking at some of your older work, and have always wanted to hear you speak about the images in your projects Cementon, Skin, and Surface Tension. Can you talk a bit about how you first entered into these bodies of work, the through lines you draw between them, and how they’ve informed where you are today?

Laura Steele: Oh god– they’re so old.

AF: Come on.

LS: I’m so embarrassed. I haven’t touched them in so long.

(laughing)

I would of course be more than happy to look back at that work with you. I do think it’s interesting though, that my initial response to that question was one of embarrassment, even though it is work I am immensely proud of. I hope we can circle back and unpack this a bit later. The inclination to feel shame or embarrassment about particular bodies of work, often our earliest creations, points to a deeply problematic way in which we have been taught to think about and assign value to ourselves and our achievements. Before we unpack that issue though, let me actually answer your question.

LS: There are three main bodies of work I made during my time as a student studying photography, which were essential to the development of my voice as an artist. It is work I find equally important today as it was then, if not more so.

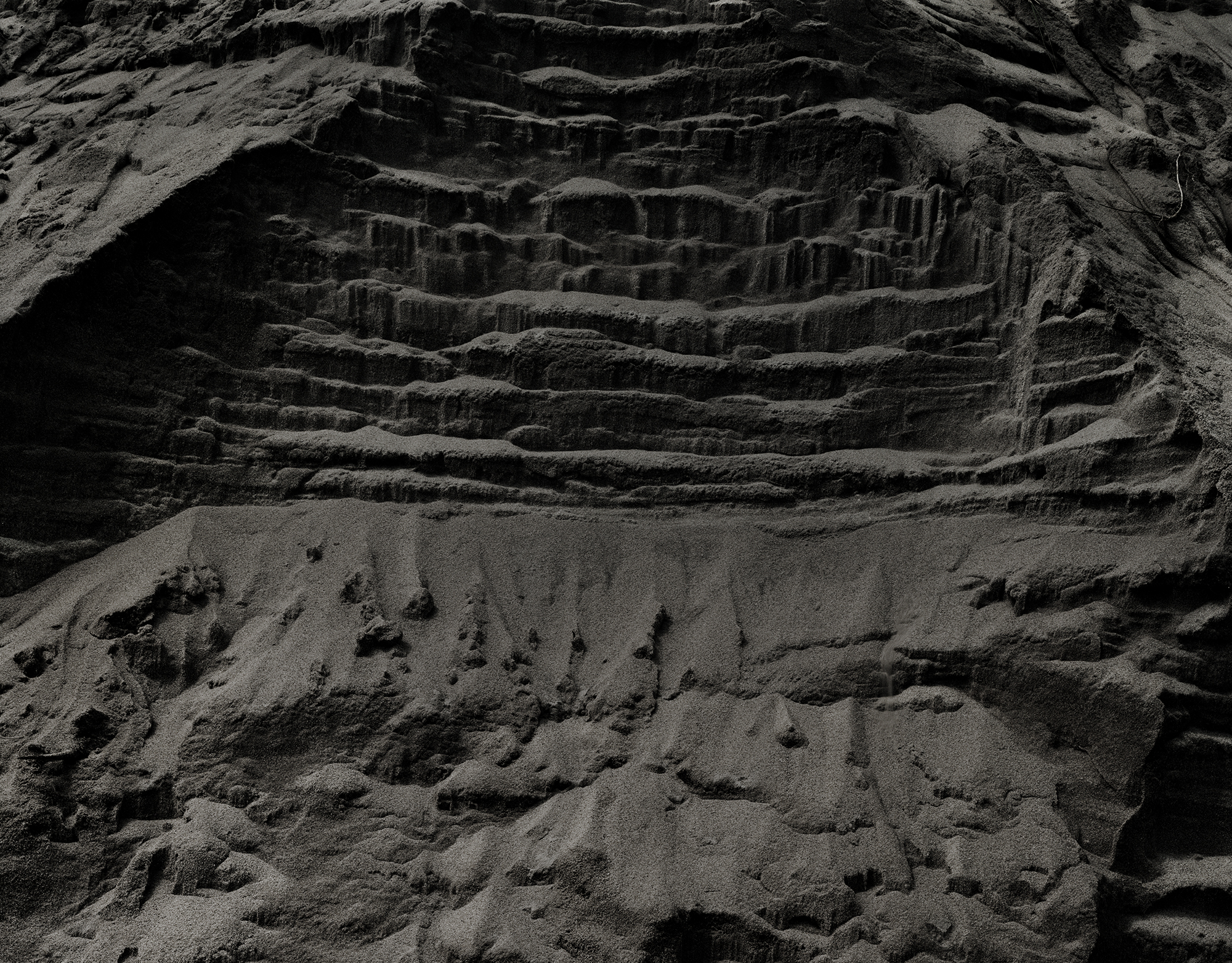

All three projects (Cementon, Skin, Surface Tension) are investigations of body and agency, and the intersection of those things with identity. It is about the social/cultural expectations of and on a body… a female body in particular. I can’t say I would have described the work in this way at the time I made it. At that time I was simply responding to an internal thrust to make work that was in dialogue with myself. Up until that point, I had kind of been invisible to myself. The work became a way for me to give form to that ghost that was being held by this body. I needed to bind it up and strip it down… to objectify it. I engaged various tools to do this, using language defined by the male gaze and in Cementon and applying a methodical scientific approach in Skin, where the body is presented as fragmented evidence of an elusive whole. Many of these elements were present in Surface Tension as well, but I also began using the photographic process to document acts of rupture on the skin itself. A surface that is expected to hold and contain the violence implicit in those social expectations which default to the objectification of female bodies.

The acts/performances described in these series were also meant to investigate the body as a site of pervasive and incessant self inflicted violence. Sometimes the references are direct and other times they are implied. Self objectification, and the self inflicted violence that can come from it, is of course a direct consequence of a social/cultural framework built on reductive and binary gender roles that describe no one and only cause self loathing when searching for alignment in its reflection.

AF: Understanding the spaces, both mental and physical, that you were working from provides so much clarity to the images. I’m interested in what you said about being invisible to oneself, and thinking about the excavation from invisibility that happens (throughout one’s life) but especially in school and as youth. When I came to Bard, I began working and learning from and collaborating with people I never would have had the chance to meet before. This influx of new information was heavily influential in the development of my voice– the beginning of this excavation. The relationships I’ve been able to form with artists and mentors have been pivotal in the development of my practice, especially when it comes to looking ahead and imagining possible functions and futures for my work. What role did mentorship and guidance play in shaping your artistic practice and the way you perceive yourself and your work? I’ve been thinking a lot about how the people we surround ourselves with infuse our work and ideas with their own– whether this happens consciously or subconsciously.

LS: I love your use of the word “collaboration” to describe the way in which our experiences and relationships become an essential part of our artistic development and voice! I couldn’t agree more. I have been lucky to have many mentors and guiding voices throughout my life. When I was young and making that early work, I did not have the words or the clarity to really give voice to what I was doing. (The expectation of the art world for artists to know immediately and comprehensively what their work is about as they make it is deeply problematic and corrosive in my view. Don’t get me wrong, digesting ones work through writing and conversation is an essential part of the artistic process. But there is a desperate need to reframe how we think about that self analysis, not as something to be definitive and immutable, but as something innately variable and fluid. A more holistic understanding of a work is to accept that our understanding of it is limited and fractured and constantly changing.) But, there were people around me who were using different language to point in the same direction, and others who saw my work and gave voice to it in a way I could not.

Barbara Ess was a friend and mentor, and her work, her words and her guidance deeply impacted my practice. Her book I Am Not This Body (Aperture, 2001), modeled an artistic, spiritual and political practice that deeply resonated with me. Her voice and her work functioned not only as inspiration but perhaps equally importantly as a kind of permission to make meaningful photographic work that reflected the inner rather than the outer world. This was especially impactful in a time when a straight photographic language and practice was valued above all else.

The poet Robert Kelly was another person who had a profound impact on me. He reached out to me during an exhibition of the Surface Tension work. He saw the project and gave voice to it with a clarity and eloquence that shook me to my core. It still does. He’s a poet so his words are like arrows into the heart. I don’t know many people like that. Have you ever been in dialogue with someone like that about your work? Someone whose art form is language, someone who has dedicated their life to studying that medium, and can wield words with that kind of finesse, exactitude and power?

AF: I am reminded of that relationship every time I sit down to read — every time I encounter a vantage that reveals a shared experience, a shared way of seeing. No matter who I talk to, listen to, read, whether they are an artist or not, I feel like they bring something valuable and palpable to the table that my experience alone would never lead me to. The specificity of language in those conversations are foundational to how I think about my work and its place in the world. I want to circle back to this idea of collaboration later.

You’ve been speaking about the entry points and ideas that are foundational to these three bodies of work, and I’m wondering if you can begin drawing ties between your practice then and now? How has your perspective on the intersection of body, agency, and identity evolved since those initial projects? Have there been any significant shifts in your understanding or exploration of these themes, and if so, how have they manifested in your recent work?

LS: The short answer is that all of an artist’s work is connected, with the artist themselves being the throughline. But I know that is probably not the answer you are looking for. Certainly themes of identity are a throughline in all of my photographs, though it is not as overt as it was in my earlier work. I am interested in the constantly shifting and fluid understanding of self and body and identity as a reflection of the world and of the culture and society around us… as a reflection of the relationships we choose and those we reject.

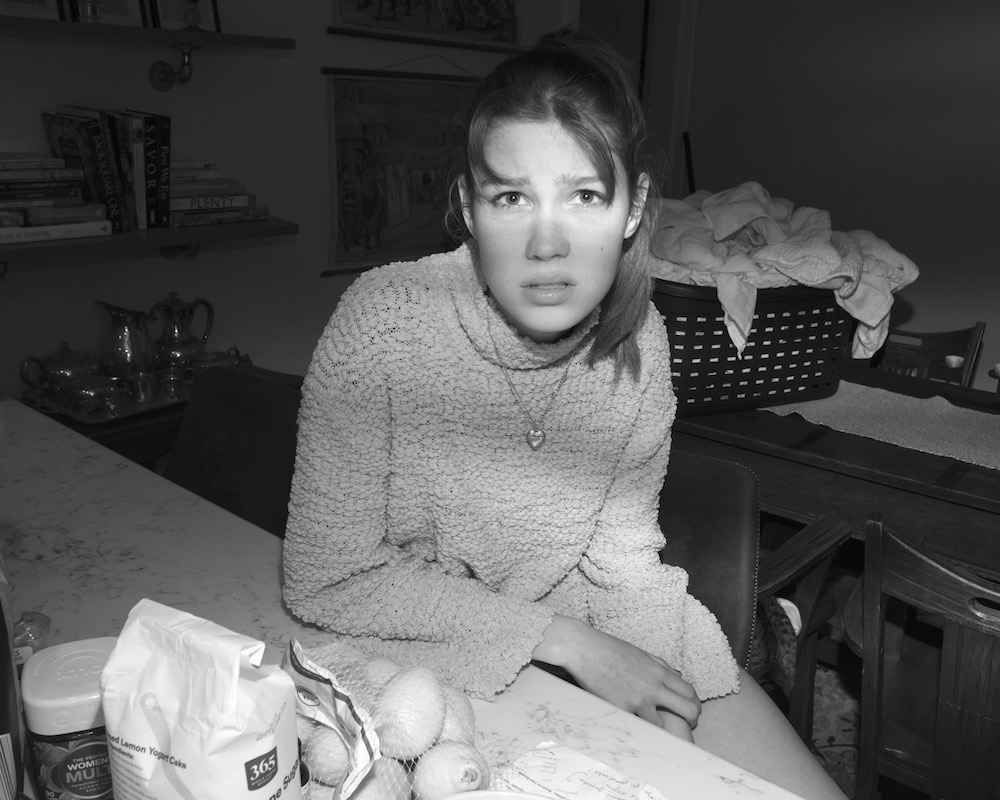

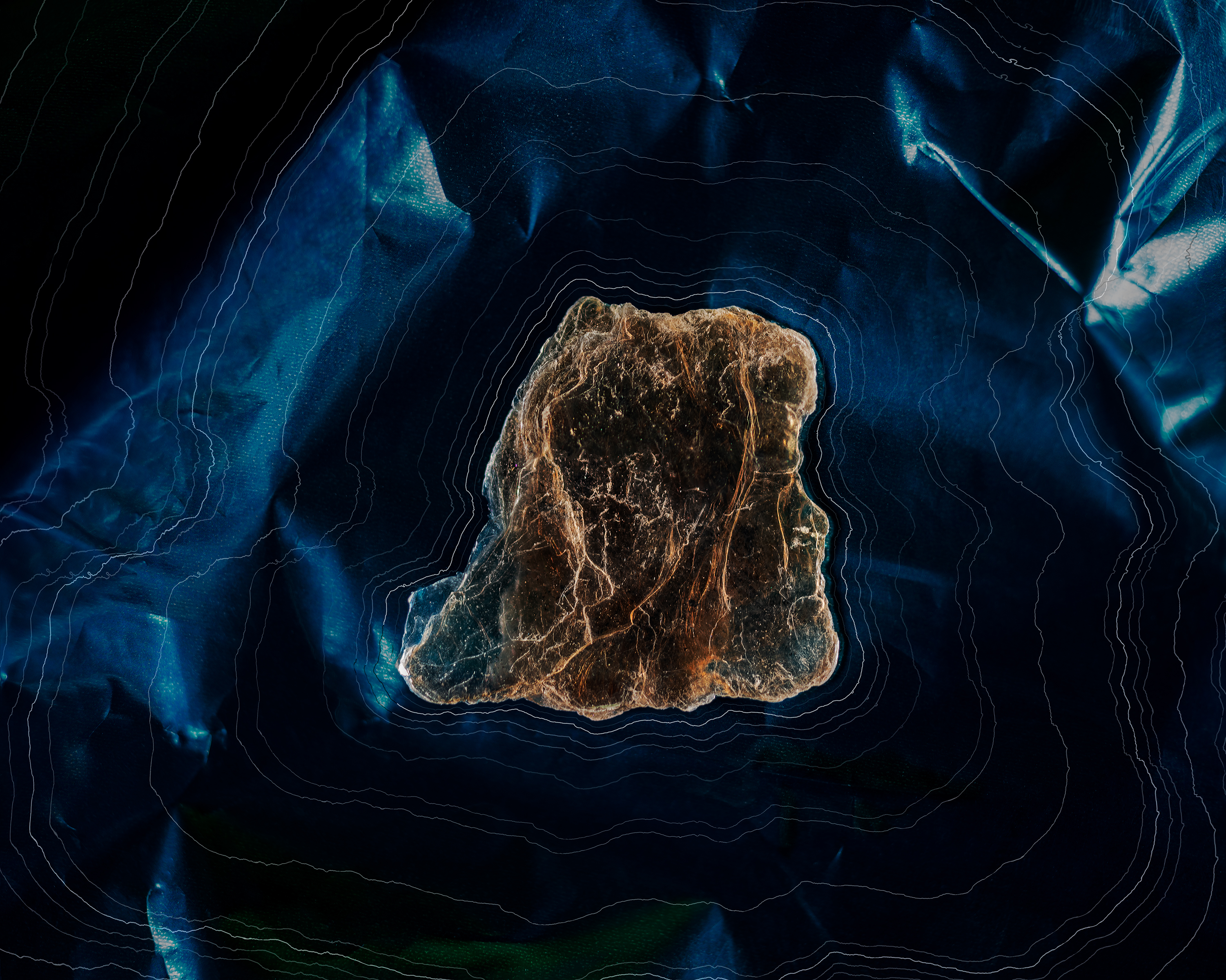

Recently, I have been interested in intersecting with spaces that push up against our expectations, where what is reflected back at you is momentarily something both familiar yet completely surprising and sublime. I was hinting at this in my earlier work, but was looking inward for those moments… using the camera as a scalpel, turning toward my body to investigate and dissect. Now I find myself pointing the camera outward, looking to find/create those transcendent spaces in the smallest of pebbles, in the exasperated expression on my daughter’s face, in the vastness of a pine forest. But really, all of these are threads that I am intensely drawn to as an artist.

LS: Not surprisingly, the works of art I am most drawn to are ones that grapple with many of these same themes. I recognize some of these ideas in your own photographs. I am always intensely moved by the way you are able to describe so many complex and often diametric ideas and emotions in one singular moment.

Two photographs in particular come to mind. In one photo, a person is sitting precariously on the end of an arched tree, not quite a sapling, but large enough to hold their weight. The tension is palpable and yet there is a sturdy lightness, as though they are floating. The weight of a body emerging, more adult than child, still levitates even while burdened by the looming ground beneath their feet.

The second is a photograph of your sister who sits at a kitchen counter staring confrontationally at the camera, the light pulling her forward out of the shadows. The viewer is met with such a dynamic and conflicting range of emotions. Her gaze is a kind of challenge for us to address everything that exists in that beautiful complexity. I am curious to hear your thoughts about what it is like for you, weaving so many threads together and with such delicacy and finesse and care. What does that process look like?

AF: My first thoughts are about the tensions within and between these threads. When I’m drawn to an image, I can often pin that response to the palpability of the range of emotion that’s at play. In this one of my sister, trust meets skepticism, theatricality bleeds into authenticity. A compromise takes place between what is and what is not– both vying for your attention. I’m trying to pull everything up, but some things beg to stay beneath the surface, cowering and cracking when they’re brought forth into the light. Photographs are so momentary, made of time. In an instant, everything is boiled down into a singular thing. How can they not be fractured, fragmented, incomplete? I’ve started thinking that each picture reveals parts of the whole, and the larger whole is something that spans many projects and many years.

AF: Sometimes I feel like the structure, polish, and presentation of these images is at odds with these themes we’re talking about. You’ve mentioned grappling with this before; how you’ve felt conflicted when the content of your work becomes at odds with its presentation. Can you talk a bit more about this?

LS: Yes! This idea of fracture is something I have been thinking a lot about recently, both with regard to content and presentation! This train of thought began when I started the process of rebuilding my website. I have always struggled with online formats of presenting artwork. It’s always felt so reductive of the work itself, and as a result a diminishment of the artist and their practice.

The formats of presentation are built on monetizing artists and their work (this is of course inevitable when living in a society and a culture obsessed with material consumption). The standard format for presenting one’s work online is to categorize and compartmentalize everything into separate boxes, or “galleries,” as though they are not deeply connected and intertwined. Most artists’ websites are organized chronologically: Here is my work from when I was a student, then here is my work 2 years later, etc.

AF: Which inherently suggests that whatever you are working on currently, the most recent thing, is more valuable, more powerful, more legitimate than everything that came before it.

LS: Right! And if you have had some success with any of your work, everything else you make is now in competition with that success. And all of this introduces unnecessary anxiety into the creative process. An anxiety that compromises and impairs the creative process. Of course this isn’t a problem for narcissists who believe everything they make is brilliant (laughing).

AF: I guess I’m wondering how you can balance the evolution of your practice with the recognition of the relevance and importance of your earlier work?

LS: This is the challenge, right? In addition to introducing unnecessary anxiety into the equation, the hierarchical framework robs us of the opportunity to understand our work in a more cohesive, dynamic, fluid and multidimensional way. I came to realize that the reason I had been so averse to updating or maintaining my website for 10+ years was because I hated the idea of forcing my work into these isolated boxes. But I have finally given in, understanding that visibility equates to legitimacy in the art and educational industry. So, I have attempted to find a way to engage with the medium in a way that would not undermine my work.

I realized that it was essential to find some small way to resist the standard format which relies on a form of stratified compartmentalization. A form I had been taught and continue to see reflected on the world around me. I was looking for a form that allowed the earlier work to be seen and understood in conversation with everything else that came after and will continue to come after. The answer I came up with seemed simple, just lay all “the shards in the dirt.” Say little and let the fractured whole speak for itself.

Ocean Vuong speaks eloquently about these ideas in his conversation with Amy Rose Spiegel in 2022 for The Creative Independent. He is speaking specifically about the concept of writing “the ghost of a novel”:

I was thinking about art, and restoration. I have this uneasy relationship with how we have this desire to restore other cultures; artifacts; art. Looking at the violences that we’ve done to one another as a species, I get anxious about restoration, because, in some cases, we are also erasing acts of violence. If it’s broken, we rebuild it; we lose the traces of what made those breaks in the first place.

What if I wrote a novel that is so fractured—so in pieces—that it becomes the epicenter of the break itself? As if to say, “I’m going to refuse to create a whole finished product, but [make] the phantom of a product—the shards in the dirt. Art exists there, too.” Even though a life is broken, it’s still worthy and capable of a complete story if we look at it in the ground zero, to the point where we can not even imagine what it looked like before the fracture.

I would like to turn this idea inwards and take it one step further by suggesting that all human beings are fractured, perhaps even more so today than at any other time. The work we create as artists are the shards and fragments of a shattered yet transcendent coherence. When we insist on compartmentalizing our work, our voice, we hinder a deeper and more meaningful understanding of ourselves, our practice and of the world at large.

There are other artists exploring these ideas of fracture. I recently had the opportunity to experience the work of Sarah Sze at the Guggenheim in New York City. Do you know her work?

AF: It’s phenomenal. Martha Schwendener spoke of her work in the New York Times as “the sense of art in the process of becoming, rather than finished and abandoned.”

LS: Exactly! I haven’t read that review, but I had a similar experience. Sarah Sze’s sculptures reflect a world and a consciousness that is deeply fragmented and chaotic. And yet even in its confusion and precariousness, I was confronted with an overwhelming and sublime beauty. The work felt both complete, and transitional. The sculptures seemed alive, as though they were evolving, and if I were to return a day later, something new and equally transformative would have taken their place. It took my breath away and was a profound and spiritual experience. I longed to experience the work away from the crowds. I think I could have stayed there for hours.

Looking at Sarah’s work made me confront how fractured we are as a society. The promise of technology and social media was that it would bring us together. In some ways that might be true, but perhaps in the most essential ways it has isolated us more than ever. By boxing ourselves in, we are simultaneously shutting out the very voices that might challenge and broaden our understanding of these things, including ourselves.

Many of the most meaningful and transformative experiences I have had as an artist have happened in my collaborations with other artists. I use the word collaboration broadly, as you did earlier, to include interactions and brief or ongoing conversations, whether or not they are part of a specific art project. I also think of my photographic work as collaborative. There is an inherent alliance, a partnership with whatever I am photographing, but especially when I am working with portraiture.

Portraiture seems to be an important part of your practice. Every depiction seems to reflect an incredible intimacy and ease with the people you are photographing. I am thinking about the photograph of you and your mother, sitting together, shaded by the luminous branches of the willow tree. Do you see that work as collaborative? Is there something about your approach, your process, your relationship with the people you are working with that elicits these potent and tender moments?

AF: Our relationship is deeply collaborative, rooted in friendship. There’s always an underlying understanding between us, where explanations are rarely needed. We see and understand each other, even in moments of unspoken emotions. We reflect aspects of ourselves in each other. When I attempt to capture others with the same intimacy as I do with my family or close friends, I find it really challenging, at times insurmountable.

AF: Can you talk to me a bit about your collaboration with your daughter Lyra?

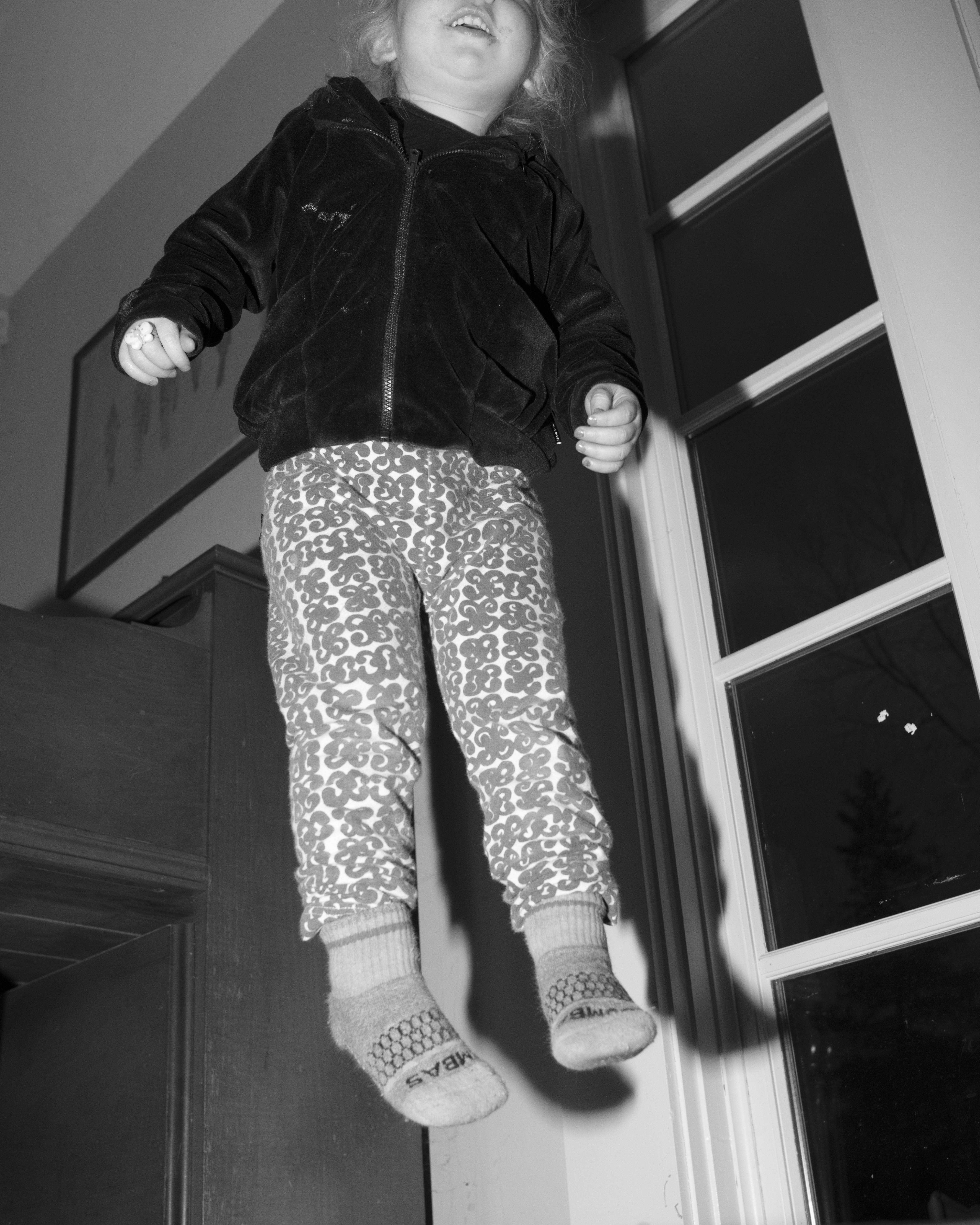

LS: Collaborating with Lyra has been incredibly powerful and challenging. She is 9 now, but when Lyra was between the ages of 2 and 5 years old, we collaborated on large 3×5 foot drawings/paintings. We taped watercolor sheets to the floor and worked on it slowly over a period of months. It was fluid and always evolving and a deeply beautiful process. By 4 or 5 years old though she began to lose interest and would get agitated with me at any interactions or engagement I had with the process. She didn’t want me involved, but then seemed less interested in working that way by herself. As she has gotten older, we have attempted collaborations with photography, writing, sewing, and even painting again, but it often ends in frustration for her. And what is always intended, equally and sincerely by both of us, to be a collaboration, ends up feeling more like a competition for her.

LS: I believe this reflects a deeply innate and complicated relationship humans have with the tensions between collaboration and competition which goes back to our childhood. I see my own daughter contending with these issues. I see myself struggling to find balance, to know how to implement a framework of support that fosters and models the incredible power and joy that can come from a collaborative experience. But I am fully aware that I am trying to do this in the face of a society that values and emphasizes competition above all else. It is an overwhelming force to contend with as a parent.

At the same time, I recognize and deeply appreciate the reality that growing up demands a child find their own voice, unique and independent from their parents. We are born, like it or not, contained and defined by the identities of our parents. Growing up, by necessity, involves a life long journey of rejecting that identity foisted upon us, rejecting our parents input, in order to make space to cultivate our own identities. Hopefully it is something we outgrow as we enter adulthood, but even there, even when parents are absent or have passed, it is hard to see ourselves without their reflection looking back at us, for better or for worse, whether we can find a way to embrace and incorporate that reflection meaningfully into our lives or not.

I guess I see my life as a collaboration. Lyra is as much a part of the work I make as I am. All of my creative decisions are deeply influenced by her. If my work is an extension of me, and my experiences and my relationships with the world and the people around me, then how can she not be a significant influence on my process. Equally, my partner John is a collaborator, my students, and colleagues are as well.

Relationships with people that are sincere, meaningful and foster an equitable exchange of ideas that challenge our understanding of ourselves, will always lead to deeply meaningful experiences. Any experience you open yourself up to in a deep and meaningful way will significantly impact the work you make as an artist. This may not seem like a collaboration to most, but at what point does something go from being influential to collaborative? I don’t know the answer exactly, but maybe I prefer the term collaboration because it elevates the importance of those who were integral to the creative process and hence the resulting artwork.

LS: I am not sure how we separate those things, or why. I suspect it has to do with a capitalistic mindset. That presenting works of art as collaborations would completely undermine the profit structure, where the singular “genius” artist, presented as a kind of godlike figure, (unexplainable, somewhat mystical, with superior mental or spiritual abilities to translate the world for the rest of us) is a deeply relied upon industry brand. The designation is more of a mythology than a truth, a bit of semantic manipulation which ensures investors that the value of the artwork purchased is justified. It is a designation that is simultaneously ubiquitous and strangely elusive with regards to the criteria for who gets bestowed with this designation. Strip away the godlike concept of the genius artist, and we are left to contend with a more complicated (and far less romantic) understanding of what social and economic infrastructures need to remain in place in order to make the great artist as historically defined by western culture.

If I look back at creative collaborations I have done over the years (using the more narrow and traditional understanding of that word) I would say that collaboration is not a singular experience. Some have been deeply meaningful and transformative, others quite toxic, painful and damaging. All have been valuable. Ultimately, it’s a relationship like any other, and requires all the energy and attention that a familial or romantic relationship requires in order for it to be healthy, productive and worthwhile. All people involved have to be committed to maintaining a space of generosity, honesty, and equity through thoughtful and respectful communication and most importantly need to actively participate.

Unfortunately this is not a space that is well modeled in our society or our educational systems which are built on competitive principles. We are taught that success is measured by an individual’s financial worth and that competition is not only healthy but necessary to achieve such “success.” The result is a combative hierarchical mentality that values the individual over the group, and that leaves little room for true and balanced collaborations. As a consequence, when collaborations are attempted, there are few role models to show us how to navigate the difficult terrain of generous and thoughtful communication, fair and equitable decision making, fluid rather than rigid thinking. Instead, the tendency is to prioritize ego and self-image over process. The ego centers itself as being of primary importance, rather than the work/task at hand. For artists the work at hand IS the creative process.

AF: It’s almost as if when you’re prioritizing the process of collaboration, the process is being in conversation with the work itself. The work becomes an equal partner. I feel like so much of your process happens after the initial shutter release. There’s so much unfolding that happens after that.

LS: Being in conversation with the work beyond the split second that the photograph is made is as exciting to me as the making of the photograph itself. This, of course, could mean so many different things. For me, even the process of retouching a negative, has so much value. You’re zoomed in to a photograph in a really intimate way, and for me, it feels like I’m in conversation with that one piece of artwork in a way that is deeply essential to the process. Whether I’m spotting it, or making a selection in an area, I have to really get close in a way that allows me to interact with it at a kind of DNA level. I start to notice little details that would be impossible to see otherwise. In that way, I feel like this process allows the photograph to really tell me about itself, to direct me and guide me. The more you’re engaged in those decisions and in that conversation, the more intimate your connection with that image is. For some files, that process can take many weeks. I’m allowing myself to be obsessive. After hours working on a file, sometimes I realize that what I’m doing isn’t working. And I have to delete it all and begin again.

AF: When I was creating the image of the snakes entwining and overlapping, I was able to see the structure unfold in front of me as I was working. The amount of time spent with that image completely altered my relationship to it. You begin to understand it so thoroughly, so intimately. Details of the image get under your skin like lines of poetry.

AF: In much of your recent work, you’re shifting from working in large format to your iphone, from a slow and meticulous tool to one which is far more forgiving and mobile. Can you talk a bit about how you’re feeling about this way of working? What are you learning about process and the ways in which bodies of work can come together in less formulaic and traditional ways?

LS: For me, neither the process, nor the format, is, or should be, singular or prescribed. The process is informed by what I am trying to communicate. The tools I use are going to be an essential element by which the work is described. But, as someone who has been working with and in this medium for 25+ years, the tools are secondary to the intentions of the work and the circumstances surrounding its creation.

If the work is shot with an iphone, or a 4×5, if it is in color or black and white, is all in service of a larger concept. This can feel uncomfortable and confusing, for sure. But I do it anyway. I guess I feel like it should be uncomfortable. If it’s not uncomfortable it is not challenging. If it’s not challenging, it just feels boring and predictable. When I’m boxing the work into a category, or a singular approach, it feels too easy, too reductive.

Recently, I was putting a lot of my work together in one space, older work with newer work, black and white with color, film with digital. It started feeling much more holistic and more representative of my voice than if I had categorized the work as so many artists do (color work made with a 4×5 camera over here, cell phone photos over here, black and white work down there, etc.)

AF: I haven’t shot any color in over a year. I am so used to seeing in black and white right now. To introduce color to that equation feels like blowing it all wide open. It feels unpredictable and out of control. I know how my voice works in black and white and I don’t know how my voice works in color, but color works subtly in a way that blurs the lines, lending itself to ideas I have been working through about oppositional states and intersections that brings about something entirely new. I think it brings movement and fluidity and allows me to not categorize my work (or myself) in one defined way. Allowing myself to use black and white and color simultaneously speaks to contradictions and focuses on the tension between spaces, between people, and allows me to assume the identity of being both an outsider and insider trying to look deeper into my own world.

LS: I’ve always been curious about that but I’ve been hesitant to bring it up. I have always thought your color work was incredibly strong and I am excited to see how it might play a role in your future work. But that feeling of discomfort you express seems important and something to pay attention to.

Naturally, when you know your language, when you can communicate in a particular way, there’s a fluidity and a flow that you can get into that is transformative. This can be a deeply meaningful way to work. It’s when you begin making rules that you begin boxing yourself in. But sometimes it is hard to know when you are still in a creative flow with the tool you are using and when you are leaning back on what you know and what is comfortable. It can be really hard to know where that line is. You shift over that line when it’s more uncomfortable to remain doing what you’re doing than it is to do the new thing. Even then, it can be scary. It’s cliche, but whenever I have found myself at that juncture, it really does feel like I am jumping into a kind of void, like I am choosing chaos over order.

But I am sneaking up on 50, and I have had a lot of transitional moments in my life and in my creative practice over those many years. Those shifts happen slowly and then all at once. They are specific to the individual and their circumstance.

You indicated that you don’t know how your voice works in color. I would love to hear you talk more about the relationship between your creative voice and the tools you use to articulate that voice. Can you expand on that a bit?

AF: I can’t remember the last time I pushed myself over a line like that.

I feel like it’s challenging to know how to speak clearly and in my own voice when I’m working in a way that is unfamiliar. The discomfort comes in when I think about the color diluting or altering the black and white– that vision and that way of working.

It’s not that I’m unfamiliar with color as a concept or technique, but rather that I haven’t fully explored it as a means of articulating my creative voice. There is an inherent risk in translating what I have developed in black and white into a new palette. It’s almost like starting from scratch and finding a new way to express myself.

LS: Yes! I definitely know that feeling. I think the confusion is also part of what I am trying to explore in my own work. But I hear you. How can we visually communicate an idea in a way that is comprehensible and meaningful? Sometimes making work within specific parameters can help to clarify an idea! And sometimes, the more you try to control it the more confusing it gets. It’s this in-between space of meeting the work where it is, and allowing it to meet you. For me it doesn’t always feel like stable solid ground.

AF: It also feels like making my content line up with my mode of working. Making something that already feels unstable even more confusing. I’m already making work about these things, so it’s important to ask how I can create in a way that mirrors what I’m trying to say.

LS: I don’t know about you, but I also struggle with that space between the making of the work, and making sense of it. Self doubt and judgment can creep in too easily, especially when the work is deeply personal. It is such a delicate balance between trusting your intuition and asking deep and hard questions of the work. It’s hard to get perspective when you are in the middle of it. And if we wait to get feedback, we’ll never move forward and progress.

AF: The other end of the spectrum, something I deal with often, is stopping yourself before you even begin.

LS: Yes… There are so many pitfalls to navigate! I would say it gets easier but I don’t know if it actually does. It feels like standing on a ship in stormy waters. Occasionally the boat climbs to the top of a swell and you get a peek at where you’re going. Sometimes it’s just a glimpse and other times you are there long enough to study the landscape beyond. If you are lucky, there are one or two people there with you to deconstruct the significance of what you are seeing. Flat and still waters can be maddening, but can also be transformative. It can be a moment to stop and be attentive to the voices that are otherwise drowned out by the storm. But if the waters remain flat and calm for too long, you can get stuck. The rupture of a storm or the release from still water; both are transformative, and what comes after is always clearer.

Alice Fall (b. 2000) is an artist living and working between Oklahoma City, Oklahoma and Hudson, New York. In 2022, she received her B.A. in Photography at Bard College. The second place recipient of the 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize for her most recent body of work I Went Back to Sit in the Sun, Fall’s images inhabit a world that is alive and full of movement, fixed in the frame but still unfolding, growing from within. While engaging in ongoing collaborative photographic conversations such as A New Nothing and From Here on Out, Fall opens up spaces of unreality through an exploration of intimacy, tenderness, and vulnerability, and the fragility, perpetual tension, and transformation of these forces.

Follow Alice Fall on Instagram: @aliceflanneryfall

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photographers on Photographers: Jessica Hays in Conversation with Dana FritzSeptember 2nd, 2023

-

Photographers on Photographers: Idalia Vasquez in Conversation with Ana Casas BrodaSeptember 1st, 2023

-

Photographers on Photographers: André Ramos-Woodard in Conversation with Prince Varughese ThomasAugust 31st, 2023

-

Photographers on Photographers: Evan Baden, Aaron Canipe and Sara J. WinstonAugust 30th, 2023

-

Photographers on Photographers: Ian White in Conversation with Curran HatlebergAugust 29th, 2023