Photographers on Photographers: Brian Garbrecht in Conversation with Eli Craven

Since I first saw Eli Craven’s work back in 2019. I was drawn to the craftsmanship and dimensionality of it. There is this way his work can draw you in to examine it from all angles. Mirrors or polished metal provide the effect of lending to an image rather than simply reflecting on what has already been seen. Like it is their way of giving back to the image that their presence hides. Craven’s creations often obscure an image, but provide evidence of his influence. What is underneath may be hidden from view, but both what we see and what we don’t make the finished work what it is. In this, it is both Craven’s and yours as his work invites you to look, and look some more, maybe while it is looking right back at you.

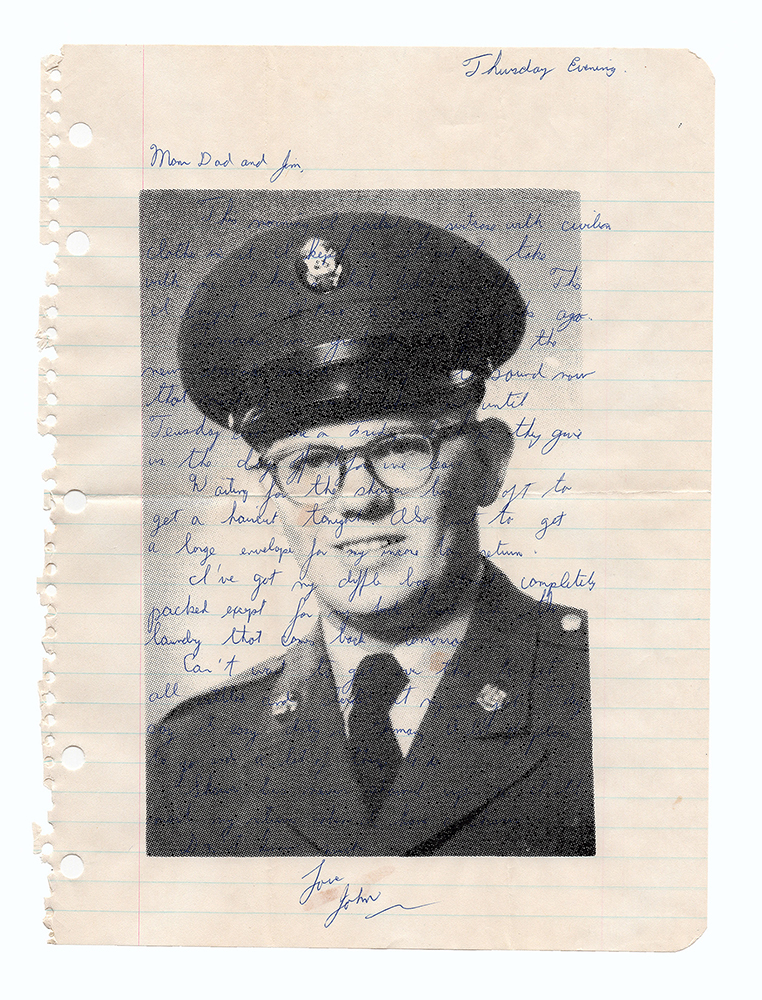

Eli Craven (b. 1979) is an American artist currently based in Lafayette, IN. His

conceptual practice re-evaluates the physical and psychological potential of the image

through sculptural and digital interventions. He combines his own photography and

sculpture with found imagery to create works that exist somewhere between the image

and the object. Craven is particularly interested in the ubiquitous and mundane imagery

found in family portraiture, self-help books, and instructional guides. Upon close

inspection, these often allude to a range of human fears and emotions. The result is a

critical investigation of the image focusing on themes of socialization, sexuality, death,

religion, and ritual. He has shown his work worldwide, including exhibitions at the South

Bend Museum of Art, KlompChing Gallery in Brooklyn, NY, and the Feinkunst Krüger

Gallery in Hamburg, Germany. Craven obtained his BFA and MFA in Photography at

Boise State University and the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign respectively, and

since 2019 the artist has been active as an Assistant Professor of Photography at Purdue

University.

Follow Eli Craven on Instagram: @elicraven

Brian Garbrecht: Outside of being an artist and educator, what are some of your interests? Maybe outside of the main things that people may already know about you?

Eli Craven: I’m also a gardener. I like to garden and I’m really into trees and manicuring, or working in my yard. So spring and summer, when I’m not in the studio, I’m usually outside pruning trees, weeding, or planting things. As an artist, I do come from a photo background. I am also a woodworker and you can see where woodworking meets my photography or collages. So that’s another hobby too. I make all of my own work, but I also make other things out of wood for the house, or for friends, or whatever …If I wasn’t an artist, maybe I would be into horticulture, an arborist, a landscaper …maybe I’d be a woodworker, or furniture builder.

BG: Where did your interests in gardening and woodworking start?

EC: Well, the woodworking really started when I had some photographs that needed to go to an exhibition and I needed to frame them. With the complications of paying for a good frame, paying a good framer, or finding really cheap frames to fit the work. I just had to teach myself how to make my own frames quickly, because I couldn’t afford it. I was making my own frames and getting more and more comfortable in the woodshop. Then, after grad school, I was teaching, doing some adjunct work, and looking for supplemental income. I ended up apprenticing with a woodworker and a furniture builder in Boise, Idaho, and made furniture there for a few years. That solidified my interest in woodworking and this really married my art practice with woodworking as well.

I think I’ve always been really interested in nature, but it was just this recent move into a new home in February of 2021. It was this blank slate sod lawn, there was not a single plant or a tree. Just a big grassy lawn. And I’ve never been attracted to the traditional suburban landscape of green grass, maintaining it, mowing it, watering it; for this flat look. And so, my wife and I immediately started digging in the yard, planting trees, flowers, grass, and plants, and landscaping it.

BG: When did you get introduced to photography, or when did your interest in it start? And going off of that, did you always view photography as an art form, or is that something that came later?

EC: My interest in photography came when I was young, maybe when I was in grade school, but possibly as a teenager. I was interested in music, and skateboarding. In the late eighties, early nineties, we didn’t have a lot of money. We didn’t have cable when I was really young, couldn’t afford a lot of movies. So, I would get magazines from friends, and collect magazines. And that was my window into pop-culture, to see what was cool, what people were wearing, what other people were listening to. And I was living in a small town in Idaho Falls, Idaho, without the Internet. Information just traveled so slow, you’d have to go to the supermarket and look at magazines month by month, read the news or what was changing, what was outside of this little town. I was obsessed with the images in magazines. I wanted to be like some of my friends that were into skateboarding, trying to be sponsored, professional skateboarders. I was naive, young, and I wanted to be a skateboarder. But I wasn’t very good, not good enough, anyway. And so I thought, well, maybe I could be a skateboarding photographer, or I could be a photographer that took pictures of bands, you know, like to make album covers. Or, take pictures with bands on tour or at live events. That was kind of an early idea when I didn’t really understand the industry at all. It was just based on the fact that I was really obsessed with looking at images from a very young age as a means of learning and discovering myself. I quickly found that it’s hard work.

I bought a camera when I was a teenager, 18 maybe. Taught myself, I made a little darkroom in the basement and started to learn how to do black & white work. It wasn’t until I decided to actually go to college and took photography classes in an art department that I was introduced to it as an artform. I saw it as a technical skill, more like a journalistic endeavor. And then, when I went to art school, I saw that you can carry ideas or make meaning out of it.

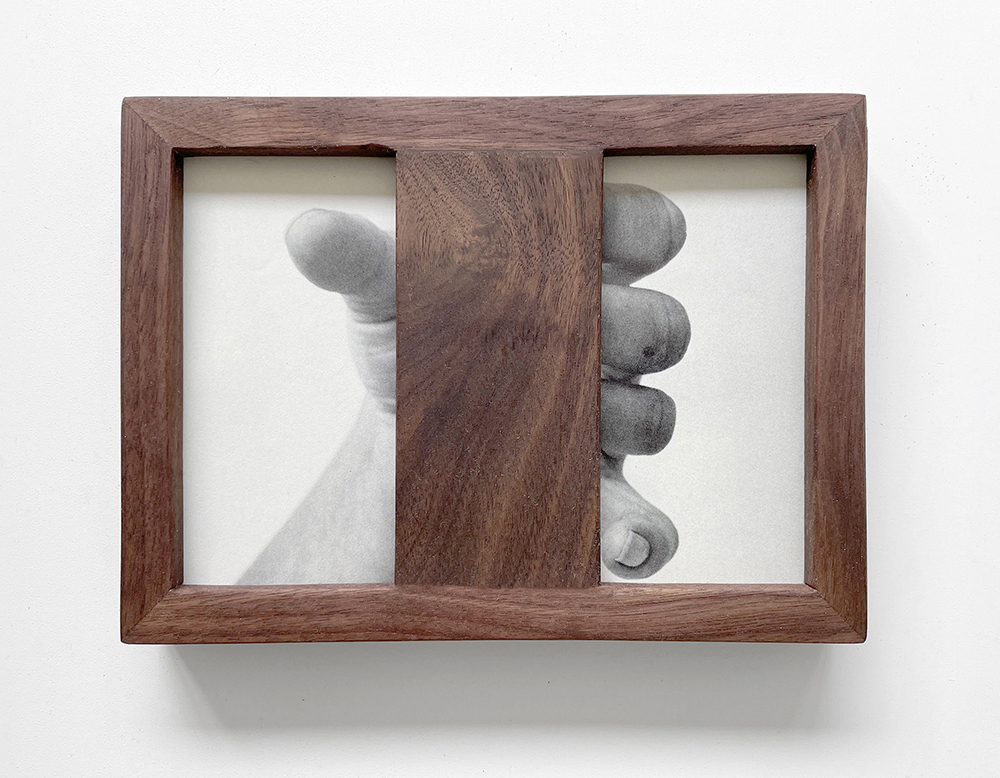

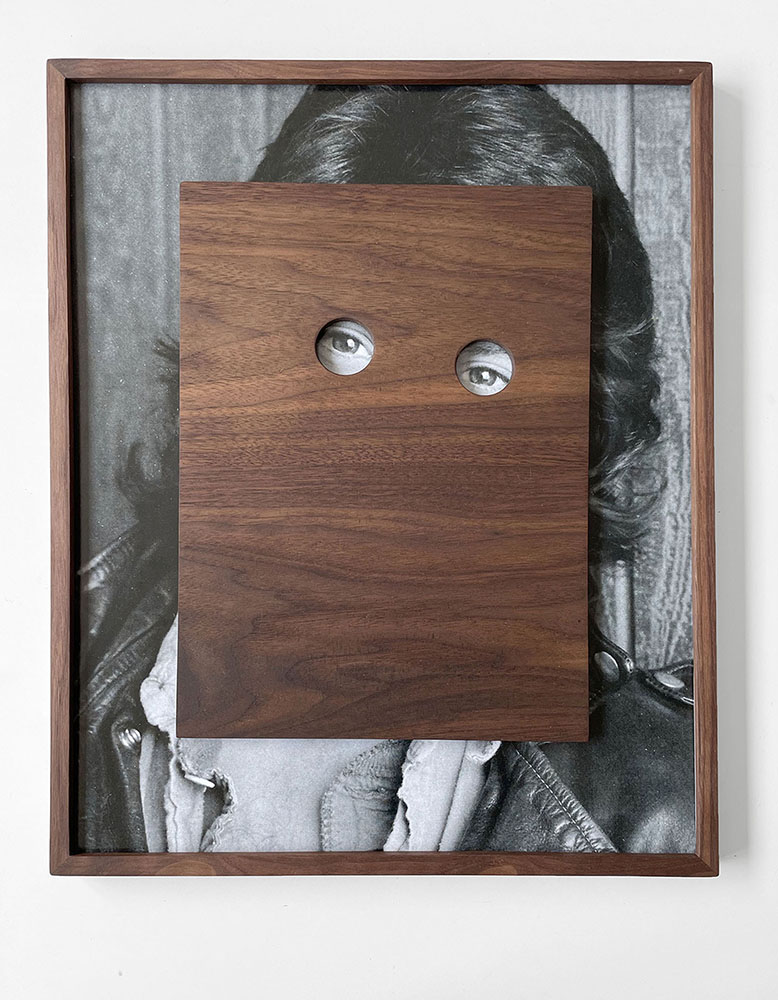

BG: I want to ask about the way you use wood and other objects to obscure parts of your work, and other times it is like you are letting the viewer in a bit with the way you put holes for the eyes of the image peer out. I wanted to know more about this obscuring and if it is saying something more about you, or the viewer?

EC: It probably varies a little bit, but I think it can be about “us,” you know, I think both. I probably do some of these things subconsciously, but I want the viewer to have an experience with the work. In some works I’m totally obscuring the focal point of the image, or the majority of the body or figure. It could be about the removal of any identifiable body parts, or removing the focal point, just to look at form or figure or gesture. It has something to do with how I feel about images,but I also want someone to think as they approach the work. When I’m breaking up the image using mirrors, it becomes an object that you have to walk around and look at from all angles. As it changes, it tends to be more about the viewer’s experience. I think about these images and what they represent. I don’t think about them necessarily as what they are, just the two-dimensional flat paper surface. I think about where that image came from, what it represents, its source. What’s the scene we’re looking at? And then what happens to the scene when there’s a big chunk of it missing.

BG: I was also wondering about the way you use brass. Was there a specific reason for using brass? I saw that you were using mirrors in a similar way in your earlier work to block or reflect parts of the image.

EC: I start using materials sometimes by chance. The same way I might find a found image, or stumble upon something at a thrift store. I go to hardware stores or resellers of building materials. I’m just looking for wood or anything. I had already been playing around with putting mirrors in my work, but the mirrors were so fragile they couldn’t be shipped or they’d break. I found a polished sheet of brass. I think it was a kick plate for an industrial door. So that was the first time I used that material just because I found it. It’s highly reflective, just like a mirror. It looks beautiful with the black and white imagery. After I had used it once, the more I thought about the contrast between the image and the color of the metal, and then the fact that it’s stable. It makes it so much easier to transport the work. But I also really like the color too.

BG: I don’t know exactly how to put this, but for me, while viewing your work I get a sense that when you obscure parts of a person, maybe there is a sense of seeing yourself, or a way for the viewer to see themselves in your work. This obscuring can make the work feel more universal in this sense by seeing parts of ourselves, without an identity or way to identify exactly what or who we’re looking at.

EC: Yeah. The work with the eyes and the little circle cutouts, peepholes, those are primarily images taken from soap operas, the daytime soap operas from the 1980’s and 90’s. I wanted to propose that we’re looking at these images, we’re looking through these frames, these photographs, but there’s also a relationship,they’re looking back at us. I was thinking a great deal about this personal history with soap operas. They were on the television all the time when I was growing up with my mother and my sisters. But, I was also thinking about the production and consumption of soap operas and their intention or their curation of these dramas of these emotional situations that are so dramatic and sometimes ridiculous. It’s like staring at a mirror, but like an amplified mirror. I was thinking about these actors looking back at me. I think that’s where it came from. It’s a reminder to the viewer, this is a thing you’re looking at.

BG: With all of these three dimensional qualities to your work, do you have a hard time with the fact that the work is kind of demanding to be seen in person, to be fully seen and understood? Is it hard for you to have to show these in a two dimensional way or on a screen at times? Are there ever times where you feel like it’s hard to get across what you’re saying when you can’t have the viewer seeing your work in person?

EC: It’s not hard, but it does come up. There have been instances where someone can’t see the work in person and they just never realized what the material was or how it was really functioning. They made assumptions about the work because of seeing it online. when they finally see it in person, and realize this is an object with depth. It’s important to see them in person. I have to use images to promote myself, promote the work to get exhibitions, but I’ve always been someone who really likes a physical experience over a virtual experience or a two dimensional experience. Maybe that’s why I make work that way. I’m not sure. Subconsciously, I just make physical things to force people to want to see them. (Shared laughter)

BG: In the way you’re bringing these different items together, is that something that you’re preplanning, sort of visually in your head? Or, do you draw things out? Or, is it happening in the moment with the materials that you have around?

EC: I have these periods where I’m starting projects, rethinking things, or I just play. That might be a moment where I make a lot of collage work. I’m looking at images, scanning images, and even playing with them in Photoshop just to see what I can do with them. That might give me ideas for other ways of working.

Sometimes it’s just chance, or the right timing for something where I might be thinking through a certain structure, or a type of frame. The frames I’ve been making recently have a center panel with a mirror on both sides to break an image into two pieces that reflect themselves. That idea came after I was making these cornered works with the mirror, and I had this thought to put them together in one structure. At the same time I was looking at images of first-aid instruction, mouth to mouth resuscitation, during COVID. So, those two ideas just kind of came together. I wasn’t planning on one versus the other. It was just that I was playing in the studio. I was playing with these images, and making collages. Then it was kind of like, ‘oh, this would work there.’ I stumbled upon it. Early on in a project, there’s a lot of stumbling, playing, experimenting. As projects develop, I start to see what’s working and what’s not working, and plot things out.

BG: This could apply to now or back when you were in college, but, who are some of the artists that you look to, or have looked to for inspiration?

EC: One of the first artists I was really excited about was John Baldessari. Someone who was using photography in collage and his conceptual work, he really opened my eyes early. I was also into colorists like William Eggleston, Stephen Shore, and Joel Meyerowitz. Quickly, I found myself interested more in collage artists handling or manipulating the medium like Robert Heineken, John Stezaker, or Sarah Charlesworth. She seemed to have a more sophisticated conceptual approach to imagery like the Objects of Desire series and the Stills series with the jumpers or people falling. I really like artists like Isa Genzken, she really does everything. Wolfgang Tillmans was a big influence early on too.

I think when I was young, I was just looking at what everybody was doing and just copying things, trying to learn, trying to learn technical skills and learn a craft and make my own voice out of it. I never really understood how an artist can work within a really strict form of parameters for a long period of time. I get bored really easily, so I always feel like there’s a change coming, and I have to do something different soon because I just can’t keep doing this. I have to move on. Isa Genzken’s work was always different, and it was surprising to see something new. She was always reinventing herself. I was excited that there’s still a voice that’s uniquely hers.

BG: As an artist, what is it like for you having to deal with the promotion and business side of your practice?

EC: I think it’s difficult. One way I’ve dealt with it is just not to. It took me a long time to give it all my energy, and I would just allow myself to have other jobs to pay for my practice. That took all the pressure off of me, you know, as long as I was paying the bills and I had art supplies, I could make whatever I wanted, and I have no concerns about it. If you dive in as a professional artist, and don’t have any other mode of income and you’ve got to work and sell and make, that sounds incredibly stressful. So, I just never put that stress on myself. I wanted it to stay fun because I love doing it, and I want to make what I want to make. It’s pretty rare that you get a lot of commissions from magazines or places with a big price tag on them. There’s so many calls from places that just want you to do work for free.

I just had to be smart about turning down the offers I really wasn’t interested in working with. Some were really going to try to twist my work into something I didn’t want to make. Then, to work with people that really respect what I do. Still, it’s complicated. Taxes, negotiations, applications. It’s such a big part of this world and we just have to set aside time. There are days where I just do computer work, writing, documentation, and website work. Production is on hold or working in the studio is on hold because there’s a list of things I have to do. Time management helps. I try to set aside a day every week or so to sit down and do promotional work or applications.

BG: I had seen you had a couple years in between getting your BFA and attending grad school. I was wondering what you did in that time between, and were you always focused on going to grad school?

EC: When I was done (with my BFA) in 2011, there was a really jarring period where I was really excited about making work. I knew I wanted to go to grad school for sure. I definitely wanted to go, but I wasn’t ready at all, and I didn’t have the money. So, I just wanted to make work for a little while, and then make a decision. I was questioning everything because I’d worked in the darkroom, and then I had no darkroom. That’s why I started making collages. I had a little shared studio space with a group of artists. We would host exhibitions of artists from other places, and it looked like a real community and we could collaborate. That’s where I started to pick up some of the ideas that I was taking to grad school. I just worked for a few years. I hung out with other artists, and worked odd jobs to pay for everything and just tried to get into shows.

Before I went to grad school it was a struggle. It was a struggle because I wasn’t a financially ambitious artist. I really just wanted to make a lot of stuff. At the time, I wasn’t so proficient at grant writing, I just didn’t have that kind of confidence. So, I worked a full time job. And when I wasn’t working, I was in the studio, nights and weekends. That’s all I wanted to do. I built up the portfolio for grad school doing that.

I think grad school, for me, was a really good experience. I went to a program with funding, the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. I had a teaching assistantship and I really love teaching. It felt like this really intense, three year residency, where I spent as much time as I could in the studio making work, producing as much as I could. I didn’t really question myself at the time. The post-grad doubt is real. You go through a program and you get all this critique, and you discuss your work, and write about your work. Once it’s lifted you’re on your own again, I started doubting all my choices. But in grad school, I just made as much as I could. It was a lot of work, I really loved grad school.

BG: As an educator, do you have any advice for people who are thinking about not just grad school, but maybe thinking about going back to school for a creative endeavor?

EC: Students seem to be in such a hurry. They really just want to apply as soon as they finish one degree and get into the other. They want to get in and go. I think that’s the mentality of an undergraduate education in the United States. We want to get it done in four years or less. We don’t want to stay any longer because it’s expensive and we need to get back to real life. At least with my experience with higher education, grad school, and continued education, I took it slow, and I took my time finding a program that worked for me because I knew it was the one time I was going to do it. To some students, when you say take a year off and make a portfolio, it seems I’m crushing their dreams, and they’re like, ‘what am I going to do for a year?’ Take your time. And, if you apply to grad school and you get into a program and it just isn’t working, or it feels wrong, pause, and go to another program. If you treat it as something you truly desire and want to do, it can be really fruitful. If you treat it as something you’ve just got to get in to get out, and you want to move through it quickly, it’s probably not going to be very rewarding in the long run. That’d be my advice. Take your time. I took my time. I went later. I wasn’t that young. I went later for undergrad too, and just wanted to be sure and ready so I could absorb everything I could.

BG: For me, a lot of that rings true as well. I didn’t start going (for my undergrad degree) until I was 27. I think I was at community college for seven years, the first few years figuring out what I wanted to do, and then two and a half more (at NEIU) for my BFA. So, I agree, taking your time, and doing it when you know it’s what you want, is definitely great advice.

EC: Life is short. It really is. But I also witnessed so many people rushing out of high school into college, getting out of college and into a career at 21, 22, and then, you can always change careers. You can go back to school, but you could also take time to reassess before you get stuck in that career, too. I think our concept of time when we’re that young is so naive. How can you simultaneously think you’re going to live forever, but also feel you have very little time to make decisions like this?

The last bit of advice I’d have, I’ve been thinking a lot about this lately too, especially with my students, is to share your work. I think that’s the whole reason we do this is to communicate. Create conversations. I make the work for myself in some ways, but I make it for other people. So, the more you share, the more feedback you hear, the more connections you make. That’s something that was really important in between undergrad and grad school for me. The community I had in other artists I was working with and having conversations with, it was just really big for me. Any time you get a chance to talk about your work, share your work, do it. Do it on the internet, don’t be scared. There’s definitely moments that I think solitude works really well for me. There are those days where I get in my own head, really contemplating what it is I’m doing, what it means, and how I feel about the work. I don’t think I would be where I am without a community that I can discuss ideas with or share the work with.

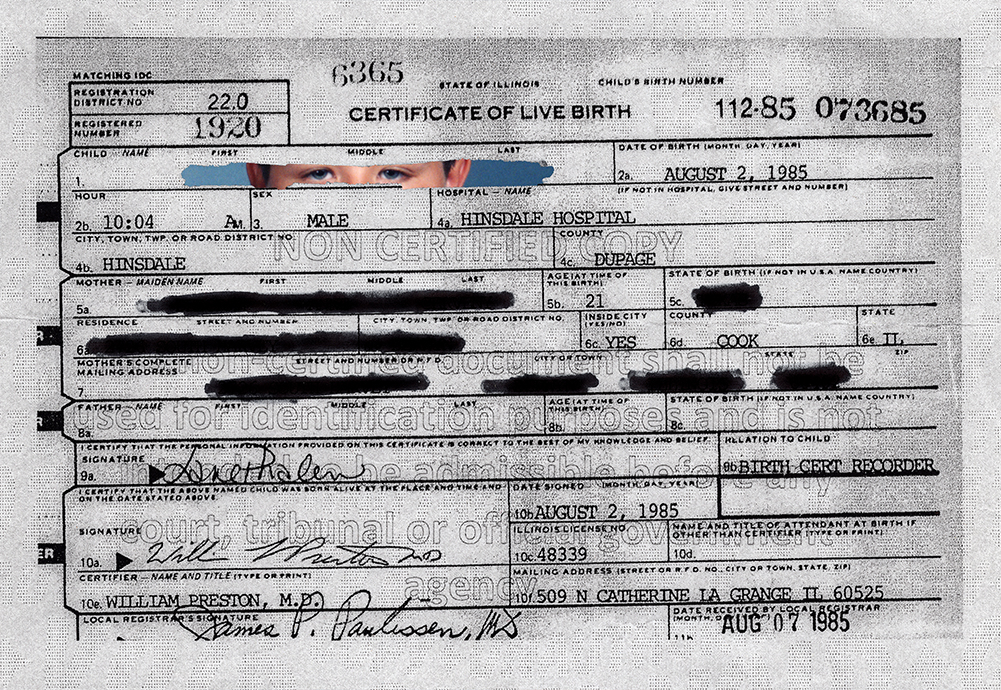

Brian Garbrecht (he/him) is a student artist from Elgin, IL. In 2022 he received his BFA from Northeastern Illinois University in Chicago, where he was a member of the McNair Scholars Program. At NEIU, he won several awards including Best in Show at the 2022 and 2023 Juried Student Art + Design Exhibitions, and the 2022 Dr. Bernard J. Brommel Award For Outstanding Student Research and Creative Activity. As an adoptee, Brian mixes photography, printmaking, time-based work, archives, important documents, and installation to explore the ideas of self, truth, family, and identity. He is a 2021 Honorable Mention recipient for the Dorthea Lange–Paul Taylor Prize from the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University for his in-progress series Forest From A Tree. He was also a 2020 recipient of the Society for Photographic Education (SPE) Student Award for Innovations in Imaging. Brian’s work has been shown in dozens of juried exhibitions across the United States, along with solo exhibitions at Bradley University, and Northeastern Illinois University. Brian will begin work towards his MFA at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln in the fall of 2023.

Follow Brian Garbrecht on Instagram: @theoryofbrian

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photographers on Photographers: Congyu Liu in Conversation with Vân-Nhi NguyễnDecember 8th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Mehrdad Mirzaie in Conversation with Liz CohenSeptember 4th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Elizabeth Hopkins in Conversation with Nicholas MuellnerAugust 21st, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Cléo Sương Mai Richez in Conversation with Shala MillerAugust 20th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Emma Ressel in Conversation with Tanya MarcuseAugust 19th, 2025