Photographers on Photographers: Erica McKeehen in conversation with Natalie Krick

Before attending Columbia College for graduate school or working at the Museum of Contemporary Photography, I was familiar with fellow Columbia alum Natalie Krick’s work. In 2010, I moved to Chicago one week after finishing my undergraduate degree in commercial photography at Ohio University. In my first few years living in the city, I felt rather aimless about my future as an image-maker. I considered an MFA during this period of uncertainty and toured the graduate photography program at Columbia but ultimately decided I wasn’t ready yet. However, during my visit, I distinctly recall seeing Krick’s in-progress works displayed in some of the student workspaces. Having come from a commercial photography program at OU, my brain was sort of broken by the idea that someone could make photographs that were provocative and that “glamor-inspired” while immersed in the “seriousness” of art school.

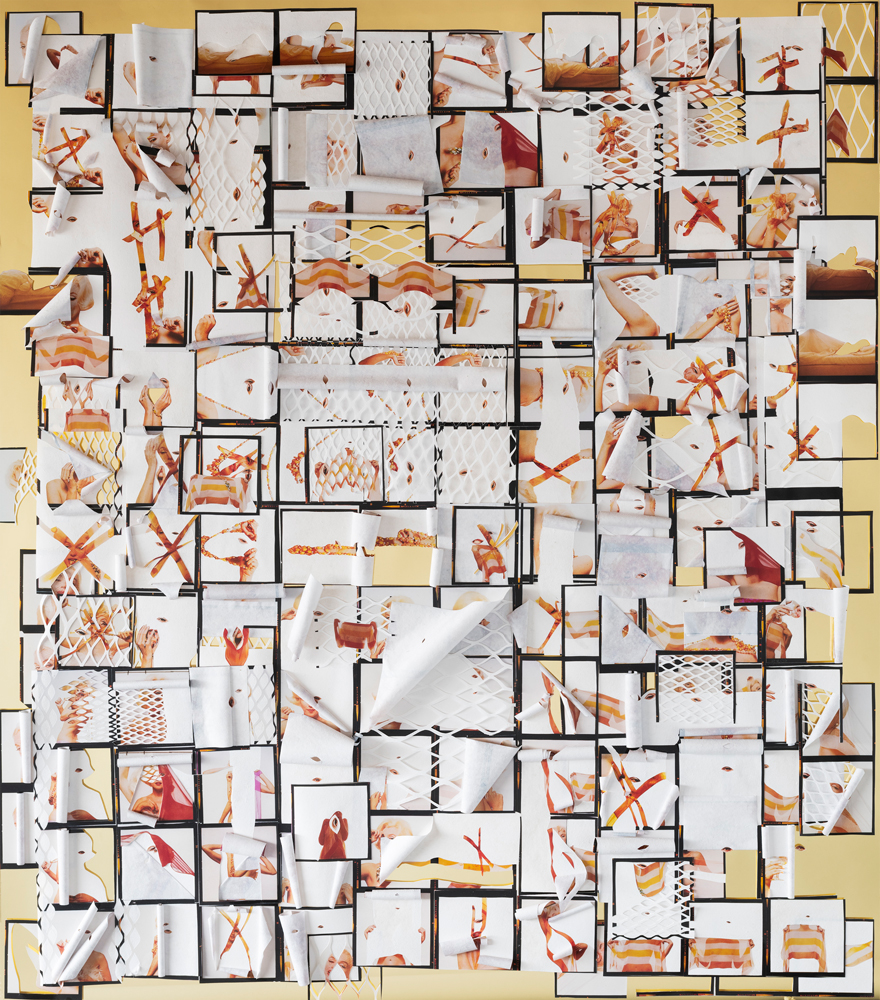

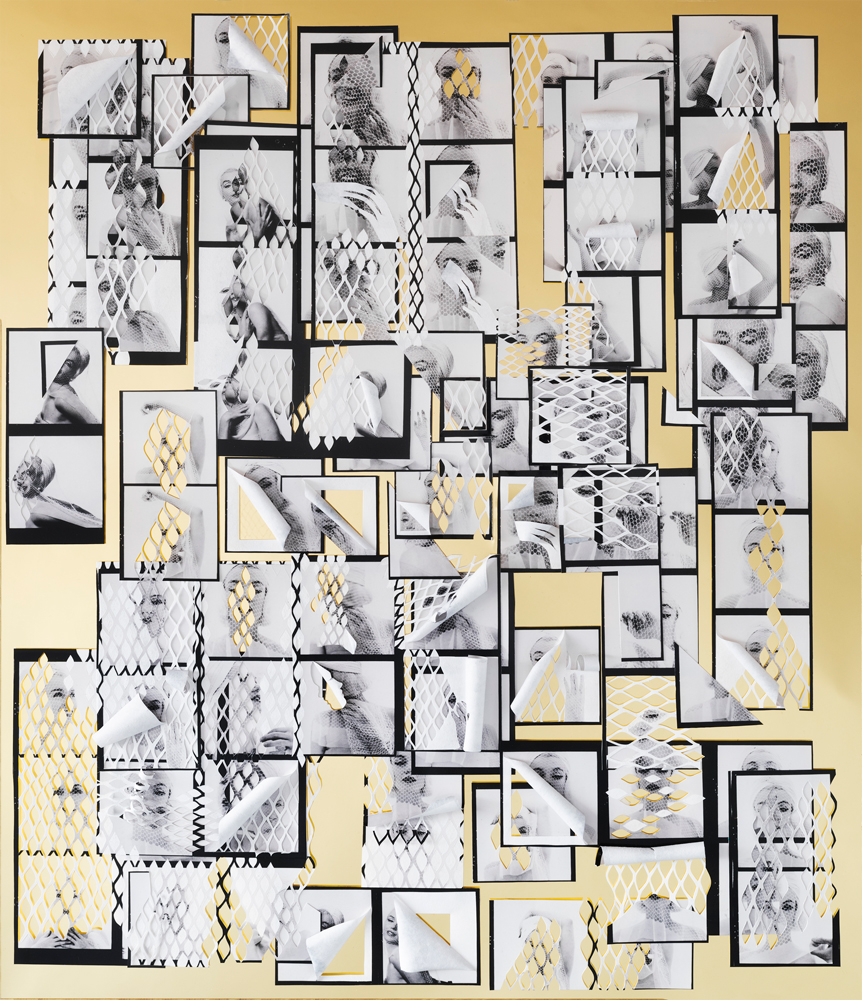

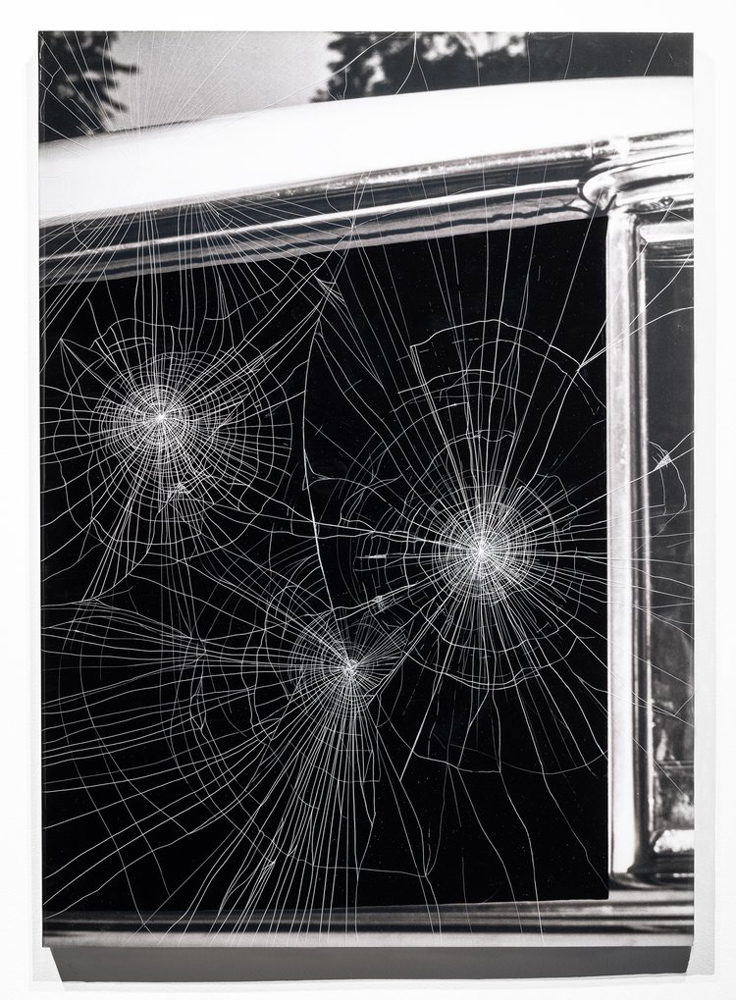

As I’ve come to interact more and more with Krick’s work, I’ve realized that the screeching volume of those first images I saw – collaborative, staged portraits of her mother – does not cease. Her work is never quiet in execution or effect. Krick’s earliest photographs made for the series Natural Deceptions take enormous risks, employ an air of unease, and create palpable tension between allure and absurdity, as does her most recent sculptural and installation work which explores the mythology behind vintage photographs of Marilyn Monroe.

Eventually, when I began my own deeper dive into visual practice and I decided upon Columbia for my MFA, I found myself further enamored with Krick’s pieces. I began working part-time at the Museum of Contemporary Photography while at Columbia, and throughout my four-year tenure giving educational tours and leading print viewings of the museum’s collection, I witnessed the undeniable pull of Krick’s work on others. Saturated colors, shiny surfaces, cut and paste, reveal and conceal, proof and illusion… visually, she presents so many entry points, especially when confronted with the physical works in exhibition.

Since attending and graduating from Columbia, meeting and chatting with Krick – a formative and inspiring maker in my own artistic pursuits – has been a pleasure. Like Krick, my work is also concerned with portraying femme sexuality (out of frustration for the status quo) and addressing notions of sexual performativity, bodily agency, and pleasure. I’m delighted to further dialogue with Krick about her practice! – Erica McKeehen

Natalie Krick (b. 1986, Portland, Oregon) is a Seattle-based artist and teacher whose work investigates visual perception and pleasure through complicating the act of looking. She holds a BFA from the School of Visual Arts and an MFA from Columbia College Chicago. In 2015, Krick was a recipient of an Individual Photographer’s Fellowship from the Aaron Siskind Foundation for her project Natural Deceptions. In 2017, Natural Deceptions was published by Skylark Editions and Krick was awarded the Aperture Portfolio Prize. Upcoming exhibitions include Digital Witness : Revolutions in Design, Photography and Film at LACMA and Boren Banner Series at The Frye Art Museum. She is also part of a collaborative duo with Kelli Connell called o_ Man which reimagines Edward Steichen’s oeuvre and his subsequent influence on the photographic medium and the history of photography.

Instagram: @nattynattynatnatnat

Erica McKeehen: In college, I felt a big gap between the work I wanted to make and the work I was making. I wanted to be edgy and sexy and a little weird, but I held back, probably because I wasn’t confident in my voice or very well-versed, and I guess others weren’t demonstrating that riskier work was possible.

And even in graduate school, I felt a little restrained. On one hand, these academic spaces should be the EXACT place for such experimentation and challenges. But on the other hand, the conditions of academia make risks difficult. When you started making photographs for Natural Deceptions in graduate school, how did you persevere with a strong vision for your images? Were you inspired or motivated by someone around you who was similarly taking risks, and how did you pivot when you were discouraged?

Natalie Krick: In my experience, grad school was not an environment where I felt comfortable failing, therefore I didn’t feel comfortable experimenting. I was young, extremely shy, and anxious in social situations. Some members of the community had very rigid and dated opinions about photography and really loud voices that were used to dominate conversations. As an artist I have always been pretty stubborn when it comes to making what I want to make. I loved the look of the flash (which was a no-no meant for amateur photographers who haven’t “mastered the medium”) and I loved making glossy (another no no) colorful prints in the darkroom. These were my tiny rebellions against making good photographs. I thought my photographs were visually alluring but also complicated. Not everyone saw them that way. I’ve had men respond to my work in really hurtful ways but in time I realized that their responses had just as much (or maybe more( to do with their own baggage as my work. I feel very fortunate that I had Kelli Connell as my advisor while I was at Columbia. Her support was crucial – she helped me have the confidence to keep doing what I was doing.

EM: Can you talk a little bit about the different relationships you’ve had with “sitters” in your work and what the process of working with others looks like to you? Obviously, as they are so prevalent in your first bodies of work, I’m so intrigued to know your mother’s and sister’s perspectives on the images you’ve made including them… but also! What about images in which you have included other members of your family? Or even dates you’ve been on (your earlier work)?

NK: My wonderful mother and sister put up with me for years and I am incredibly lucky that they worked with me although they weren’t really that into it. Looking back – I felt like such a nuisance but like I said before – I am stubborn and relentless. The pictures are about me and my relationship to photography more than they are about my mother and my sister. I spent many years photographing my friends, strangers from the internet, and men I met on dating sites. I care about people deeply, but I have no interest in using photography to prove or point to my compassion for others. Maybe that is one of the reasons why I stopped photographing people. It was never about them, and yet it was.

EM: Your work is so “layered.” I think that’s the perfect term because of the literal layering of materiality within your works (especially in your recent Monroe sculptural pieces), but also because of the visible layers of images within images, achieved through your Photoshop techniques. I’m thinking about the piece My Best Body, for instance, as a perfect example of so many visual elements and approaches coming together. Why do you gravitate towards methods of making that involve and visually SHOW evidence of so many steps and processes? How do these methods speak to the content or themes in your work?

NK: All photographs are layered objects that are easier to see as being primarily about what is in front of the lens. In some ways, this is a simple idea, perhaps even common sense – right? But this is also so easy to overlook or disregard when we are trying to navigate the bombardment of visual culture. Roland Barthes wrote about the complex interaction that takes place when a portrait is made – specifically the relationship between photographer, sitter and future viewer of the image. “Once I feel myself observed by the lens, everything changes: I constitute myself in the process of “posing,” I instantaneously make another body for myself, I transform myself in advance into an image.” I love this and I think these layers are embedded in all portraiture (although they might not be visible).

Marilyn Monroe once said “Marilyn’s like a veil I wear over Norma Jean.” I love her keen sensibility – persona as a veil. Simultaneously revealing and concealing. Isn’t that what photographs do?

I want to show my hand in order to point to the photograph as a layered object not an objective window with a fixed meaning. My Best Body came from my funny misunderstanding of the term airbrushing. Pre Photoshop – retouching consisted of airbrushing the surface of a photograph and then making a photograph of the physically manipulated print. For a long time I thought that “airbrushing” happened physically on the skin of the model. When I realized my mistake (haha), I had to make a picture that poked fun at my misunderstanding. In the photograph there is a layer of gold paint on my skin (that mimics a tan line) but I also added a colorfield in photoshop that shapes my body into Kim Kardashian curves. I want to make these layers of manipulation visible and obvious to the viewer.

EM: Piggy-backing off that last question – can you talk about your fondness for hand cutting physical photographs? When did this practice start – or was it always in place, even in earlier series? What do you see as the distinctive difference / significance in hand cutting pictures versus digitally cutting them – which you also do, sometimes in tandem with the physical cutting?

NK: Cutting photographs up is my way of playing with meaning. It’s a meditative process and a gesture of reclamation and control.

Funny enough I think it takes me longer to cut images digitally. I use the brush tool on a mask and it takes forever. I want the seams to show and I don’t want the cuts to be polished. Cutting things up physically is more fun and has given me a large callus on the middle finger of my left hand. In a new piece that I made for the Boren Banner at the Frye Art Museum – I intentionally weave physical cuts with digital cuts in photoshop – so it’s impossible to tell where the physical manipulation ends and the digital manipulation begins.

(I started to experiment with collage during my last semester of graduate school in an awesome class taught by Ross Sawyers. I was so tired of taking pictures, and Ross created a classroom environment where I felt excited about trying new ways of working.)

EM: I noticed a somewhat strategic move from the works in Repetition, Suppression which take inspiration from classic Hollywood femme fatales, to your most recent pieces about Marilyn Monroe. Along the artistic journey from 2020-ish until now, you’ve utilized an archive to physically deconstruct and reconstruct pieces that, in your words, “disrupt the act of looking.” I’ve long collected pin-up postcards of Monroe, and her glamorous image embedded itself in my childhood psyche after watching Ashley Judd’s portrayal of her in 1996’s Norma Jean & Marilyn.

Can you explain the relationship, for you, between cinematic cultural icons like Monroe, and the instability of viewing? Why use Monroe’s image specifically to talk about visual illusion?

NK: I have to admit that I was very intimidated by the idea of centering an entire project around the use of Marilyn’s image. She was born almost a century ago (1926) and her image continues to be deeply embedded in our visual culture. She is so iconic that celebrities continue to be photographed as her. I wonder how many people have encountered photographs of others posing as her prior to seeing photographs the original of her. I was struck by the omnipresence of her image – she is everywhere yet easily overlooked.

My friend Kim Beil told me about Bert Stern’s photographs of Marilyn (taken shortly before her death in 1962). I found his book “The Complete Last Sitting” through an interlibrary loan in which thousands of photographs accompanied his long text describing his ideas of her and their time spent together. His words made me feel deeply uncomfortable. In a way – I felt connected to her because of the way he saw her as an object of his desire not a subject with her own desire, sexuality and complex inner life. I know what that feels like – I’m assuming many women do and it makes me furious. Stern couches his predatoriness in naive bullshit romantic theories about photography. (“Making love and making photographs were closely connected in my mind when it came to women,”) He paints her as this tragic woman – interpreting her scrawlings on his contact sheets as acts of self-criticism. I see her mark making as an act of agency and rage. I had such a complex reaction to this book that I knew I had to work with her image. Shouldn’t we acknowledge that the majority of the men who photographed her probably shared this mindset? Isn’t that embedded in her image?

I’ve been thinking a lot about the duality of the photograph as a representation and as an abstraction. Perhaps the illusion that I keep going back to is how the photographer and the viewer play a disappearing act – pretending to be invisible when in actuality they play large roles in constructing the photograph and creating its meaning.

EM: This isn’t a very eloquent question: how do men respond to your work?

I’m not asserting that they cannot or just do not volunteer to critique or offer perspective on your work. However, considering my own experiences, feminist art, or portrayals of femme eroticism, sexuality, or anatomy often leave cishet men frustratingly confuddled. Do you think sometimes art falls into the “for us by us” pitfalls – or specifically, that your art does?

NK: I think it’s a great question! Photographs depicting a femme presenting woman have been easy and pleasing for a very long time. What happens when they are more than that? What happens when they are not easy to look at? What happens when they cause discomfort?

I love how Claire Dederer writes about perspective in Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma “Consuming a piece of art is two biographies meeting: the biography of the artist that might disrupt the viewing of the art; the biography of the audience member that might shape the being of the art. This occurs in every case.”

Also she writes “We are all bound by our perspectives. Authoritative criticism believes in the myth of the objective response, a response entirely unshaped by feeling, emotion, subjectivity. A response free, in fact, of any kind of personal perspective. For the male critic, there’s no need to question that response because the work is made by someone like himself. The work is transmitted from one type of artist (that is, male) to the same type of viewer (also male).”

As a viewer I strive to approach art with curiosity and I don’t always succeed. I want my work to be visually alluring to attract the eye, but I can’t control if people look beyond that. I can’t force them, and I don’t feel responsible for convincing them to be curious. Lot’s of art by men doesn’t interest me, but it’s not framed in that way. Are men thinking about making art that’s accessible to women? I think men need to be held accountable for this labor. When I was a graduate student in my early twenties I did not know how to say this – I did not know how to push back.

I’ve had many experiences where a man was very uncomfortable with my work. Some of these men have been quite nasty – does this make the work a success? I’m not sure? (I’m removed from these situations now but at the time I was confused and hurt – it took some time before my feeling surrounding their reactions changed)

EM: It’s so exciting to see the evolution of your work from being mostly 2D to the materiality you so heartily embrace today. Despite constantly pushing images beyond their flat, rectangular parameters, I’m curious how the image ITSELF as an intangible thing – as just a visual impression – continues to inform your practice as a visual maker.

Will images always play a crucial role?

NK: I think images will always play a crucial role in the way I think about my work but they are starting to get buried. I’m starting to exhaust them or pick them apart to abstraction. I’ve been thinking about mimicking, copies of copies and degraded images.

I looked up the definition of degrade and look what I found! Maybe this sums things up! Who degrades women? Is this inherent to the photograph? Is this inherent to being a woman? No! Yet it is an incredibly complex aspect of culture that is very difficult to navigate. I think we are both challenging that in our own ways.

Erica McKeehen (b. 1987, Bucyrus, OH) is a multidisciplinary artist in Chicago, IL. In her practice, McKeehen creates self-portraits and poetry as well as photographs and interviews fellow burlesque entertainers and members of the broader sex industry, presenting nuanced views of femme experience, sexuality, and autonomy. She works collaboratively within the documentary tradition, building long-term narratives of performers that explore identity, storytelling, and performance through intimate portraiture, interviews, and writing. McKeehen also curates and hosts public panel discussions with her peers in sex work, models and performs burlesque as Greta-X, and is the cocreator and coproducer of Lust for Life, a rock n’ roll-themed burlesque show in Chicago. McKeehen received her BS ‘10 from Ohio University, and her MA ‘21 and MFA ’23 from Columbia College Chicago. At Columbia, she received the Stuart Abelson Graduate Research Fellowship, Albert P. Weisman Award, and Fogelson Foundation Photography Scholarship, amongst many others. She currently works in community arts and lives with her two senior Siamese cats.

Instagram: @ericamckeehen

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Riley Goodman: Art + History Competition Honorable Mention WinnerApril 4th, 2025

-

Rachel Nixon: Art + History Competition Honorable MentionApril 3rd, 2025

-

Oleksandr Rupeta: Art + History Competition Second Place WinnerApril 1st, 2025

-

Jared Ragland: Art + History Competition First Place WinnerMarch 31st, 2025