Photographers on Photographers: Semaj Campbell in Conversation with Jon Henry

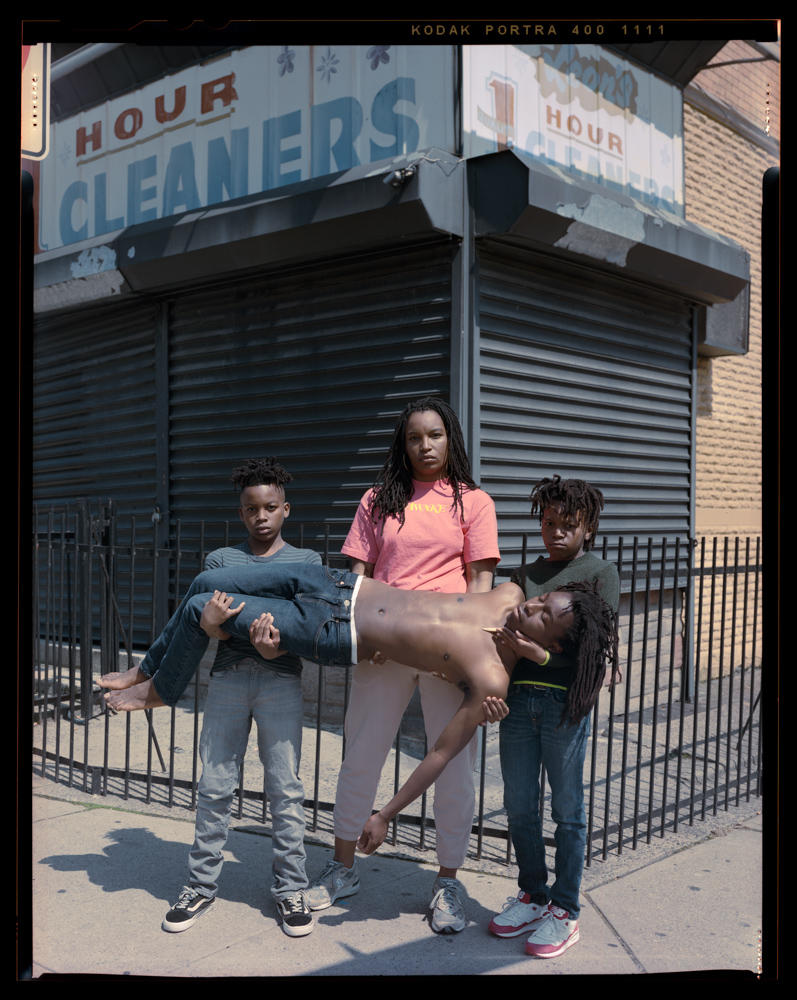

Just like every other day, I shamelessly spend countless hours scrolling through instagram consuming hundreds of images and videos. My scrolling came to a halt as I gazed at an image of black mother cradling her shirtless and seemingly lifeless son in her arms with a looming Target store symbol in the back. It was 2020, the world seemed to be going in every way but right, covid permeated the hemisphere as I watched the death toll rise by the minute on CNN. Two days prior, I watched a video of Geogre Floyd being murdered by police officers as he cried out for his mother. Prior to George Floyd’s death, I saw headlines of Breanna Taylor being murdered in the confines of her own home by police officers. Breanna and George were only a couple of the unfortunate black civilians killed because of police brutality in 2020.

For many people, especially black people, these were difficult times and brought about a sense of hopelessness, anger, depression, and anxiety. It felt as if we were being targeted from all angles and weren’t safe even in the confines of our own homes. Jon Henry’s image resonated with me on a level that only a few images have been able to do. It spoke volumes to what was taking place at the time but also spoke to the tragedies and injustices that black families in America have been haunted with for decades.

Jon Henry is a New York native like myself and we both discovered the power of the camera senior year of high school. Jon uses his large format camera to capture renditions of Michelangelo Pieta with black mothers and their sons. Jon recontextualizes the classical piece in context of contemporary issues in America and black bodies. Henry titled the project, Stranger Fruit, in reference to Billie Holiday’s song, “Strange Fruit”. The body of work was created in response to the senseless murders of black men across the nation by police violence. This conversation explores Henry’s process and ideologies as an artist.

Jon Henry is a visual artist working with photography and text, from Queens NY (resides in Brooklyn). His work reflects on family, socio political issues, grief, trauma and healing within the African American community. His work has been published both nationally and internationally and exhibited in numerous galleries including Aperture Foundation, Smack Mellon, and BRIC among others. Known foremost for the cultural activism in his work, his projects include studies of athletes from different sports and their representations.

He was recently named one of The 30 New and Emerging Photographers for 2022, TIME Magazine NEXT100 for 2021. Included in the Inaugural 2021 Silver List. He recently was awarded the Arnold Newman Grant for New Directions in Photographic Portraiture in 2020, an En Foco Fellow, one of LensCulture’s Emerging Artists and has also won the Film Photo Prize for Continuing Film Project sponsored by Kodak.

Instagram: @whoisdamaster

Strange Fruit

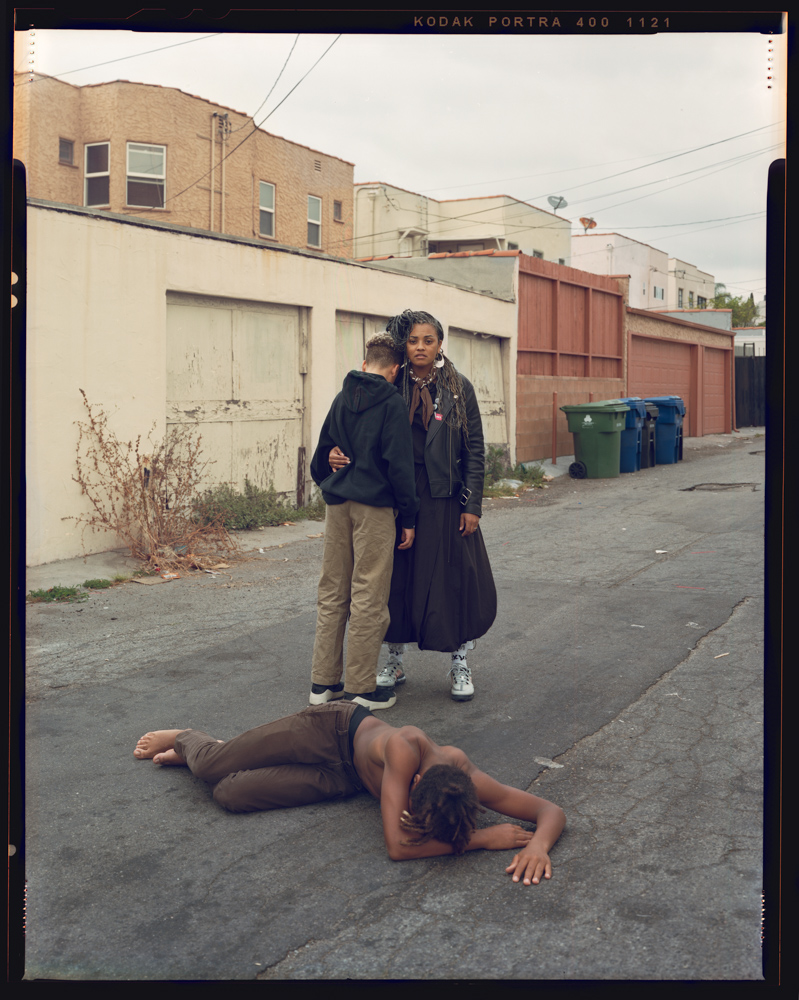

Stranger Fruit was created in response to the senseless murders of black men across the nation by police violence. Even with smart phones and dash cams recording the actions, more lives get cut short due to unnecessary and excessive violence.

Who is next? Me? My brother? My friends? How do we protect these men?

Lost in the furor of media coverage, lawsuits and protests is the plight of the mother. Who, regardless of the legal outcome, must carry on without her child.

I set out to photograph mothers with their sons in their environment, reenacting what it must feel like to endure this pain. The mothers in the photographs have not lost their sons, but understand the reality, that this could happen to their family. The mother is also photographed in isolation, reflecting on the absence. When the trials are over, the protesters have gone home and the news cameras gone, it is the mother left. Left to mourn, to survive.

The title of the project is a reference to the song “Strange Fruit.” Instead of black bodies hanging from the Poplar Tree, these fruits of our families, our communities, are being killed in the street. -Jon Henry

Semaj Campbell: Which photograph from this series has the most significance to you?

(Jon mentioned that it was tough to narrow down to one specific photo or project that was his standout because they all hold a unique value and merit.)

Jon Henry: There is one in particular that is a really heavy story that only a handful of people know and that I can’t share. But the image Untitled #61, Omaha,NE was really powerful for me because as photographers we have ideas in our mind like we have to get “this shot” and when you get there is no better feeling.

SC: Which artists have influenced you and your work?

JH: Ouuu…It’s a laundry list, there are a lot. There are those situations where you select different elements from a lot of different artists. Of course Michelangelo for the classical rendition of the Pieta…Kehinde Wiley for body placement and how to address the black body. David Driskell… he has this one specific version of the Pieta that he painted in 1956, which was a year after Emmit Till’s murder so there was this strong connection between his feelings of Emmit Till and my feelings for Sean Bell. That parallel was supremely important. Renee Cox…just the way she would be the author of the image… Hank Willis Thomas… there are so many photographers and painters who influence the work throughout the duration and continue to as the work moves forward…

There are so many folks’ images that I absolutely love like Gioncarlo Valentine, Elliott Jerome Brown Jr … .again another laundry list of folks who are making some really amazing work and I’m like damn… I want to grow up and be like y’all.. There is just mutual appreciation for folks who are out there making strong images. That’s also the beauty since 2020 where this heightened visibility of seeing all these photographers and getting to know their work more has been amazing.

SC: How do you want your work to serve in the future for society?

JH: The book exists and the project is in book form which is great because it will live forever and people will be able to access it on a wider scale. People will be able to see the full project. The mother and son images, the images of the mothers’ solo along with the text from the mothers because that is such an integral part of the work. It’s amazing to have that live on because that’s obviously going to outlast you and me. Hopefully it can open people’s eyes to reality for a lot of families that have to think about this all the time. In one form or another they all have a police story and have to have these difficult conversations with their children and it shouldn’t have to be this way. What are we talking about? We are talking about policing, they’re not only supposed to protect property but people, serve the people, serve the community and folks can’t get their minds around that… We didn’t have to see George Floyd die for 9 minutes to understand what’s been going on but some folks did and thankfully it did open some folks eyes but the price is too high…

SC: Do you see your work as black art?

JH: I just put it as art but yes, I am a black man so it can go under whatever umbrella it needs to go under. But the importance for me is that it is art and eventually all of this is just going to be art. Black artists haven’t had that agency to be like ‘yeah this is my work’ and then have it accepted by a dominating white supremacist model of getting the work into galleries or museums. But whatever label it is, the work is what it is.

SC: I only ask that question because sometimes I feel black artists get pigeonholed into everything being “black”- like everything we make has to be “black”. So my next question is, how do you see your work operating outside of the field of black art? Right now black art is trendy but how do you see your work in discussions outside the realm of black art?

JH: I think the work has been able to transcend that with many access points like the mother and son connection. For a solid 2 years, a lot people have been reaching out- actually someone reachout today through the religious aspect of the work. They were interested in the project through a religious standpoint and how it speaks to the new rendition of the Pieta and recontextualization of it. I think this can easily transcend outside the realm of just being black art but it is a concern because it’s trendy and we’ve already seen it happen as far as people getting equity. For example, shooting magazine covers or editorial work or who’s getting hired to shoot what. If I’m only getting hired to do the black story or if the queer artist is only getting hired to do the queer stories in June and I’m only getting work in February, then what am I going to do the rest of the year? I can’t just bank on that or having the Juneteenth commissions, so it’s difficult when it’s only thought of as this trend and then when the trend ends then what? Are we still working?Are we still having the opportunity to make images? I don’t know, I don’t even know how to fully combat that. I’m just trying to do the due diligence with the project and do my part.

SC: What are some of the biggest obstacles you have faced as an artist? And what advice would you give to young artists on how to go about their practice?

JH: Early on it was difficult because I don’t have a MFA, I didn’t come from a prestigious university like Yale which has the backing and support structure built in by the way of the faculty and everything else. So getting the eyes on the work and getting it in front of the right people was challenging. Thankfully I was able to make a couple of the right steps and get in contact with the right people and some of the advice I received was talking to young curators and having the work grow with them so they’ll be able to see the work now and see the work again in a couple of years. So something I always tell my students is to always know who your audience is and try to build that relationship within that audience. Whether it is commercial, editorial, fine art or museum work, establish relationships with those people who are making those decisions in those sectors.Try to stay in contact with them and and stay abreast on what they are doing, posting and sharing as well as who are those other artists they are speaking with. And see if your work is in conversation with their work and hopefully that would work in establishing some kind of community… Photography can be difficult because it’s an isolated sport. It can just be you and lonely with no one helping you and everything is falling on one person. Setting a plan of attack has helped me.

The project began in 2014 and I didn’t really start pushing it and sharing it publicly until 2017 because I wanted to have images from more than just cities. I needed my images in Alabama to at least be able to say geographically that this is something that affects everyone across the country. But it all started with understanding myself and knowing where I wanted the work to go and what that trajectory could look like.

One thing I emphasize to my students is time. It takes people different amounts of time to understand themselves and to then make work. Some people might have an idea then in a year start to crank out work. For some people it may take 3-4 years to let the idea percolate and then move from there. I began thinking about this project in 2008 and I didnt make an image until 2014. Of course I was working on other things and had the idea in the back of my mind that I really wanted to do this project but I couldn’t get there for whatever reason. It all just takes time and you can’t get around that and that’s what makes it difficult with social media with everything being NOW. So young artists have to understand that. One thing I have my students do is create a list of things that are central to you. It can be things that they want to photograph, have photographed, themes, colors, emotions and then I have them consistently refer to that list every time they make work. Therefore, whatever work their making will be of them, something they care about, something you’re interested in and this has helped students stay rooted in what they are doing… This helps with imposter syndrome or thinking that someone has already done this- because everything has been done before but things that make it essential to you are going to make it different. People have been speaking about police brutality in the black community and art forever and will continue to. When I was working on this project and doing the work I felt like the mother was missing, the strong presence of the mother and having her be the focal point of the work was something I wasn’t seeing. I then utilized that to be the vehicle to tell the story and just took off from there.

SC: How has your family influenced your work?

JH: As I was starting to make the project, I was replaying the things my mother said about being careful. When I was younger I didn’t truly fathom what that meant because as a teenager you think you’re invincible but now you see all of these tragedies that can happen and that phrase is seen in a different light. And just the appreciation for the arts came from my parents. Both of my parents were amateur photographers, and My dad was interested in portraiture as well. I picked up the camera late in high school, after my friend came to school with the first digital camera and I was like ‘ Yo, what is this?!’ I couldn’t afford one but I started to come to school with disposables. It’s kind of crazy… There’s a crazy story with Action Bronson because we went to high school together but I didn’t have the camera with me that day, so no images but I got to live the moment. But yeah,I didn’t start taking it seriously until 2008.

SC: Is there something you would like to see more of in the field of photography?

JH: Hmm… things that I care about are all these young and upcoming artists- I just want their work to be seen and collected. One thing that drives me insane in the artworld is constantly displaying the same artists. Like how many Mapplethorpe’s, Warhol, Basquiat, Frida Kahlo shows can I sit through? There are a lot of artists out here making some beautiful work, can we get them in the Brooklyn museum? Can we get them into the MET? Can we get them into a museum across the country? I just want to see better outreach and support to living artists. I would love to see local photographers in museums and it probably would bring more people into those spaces. The scope is too narrow, where the same like 6 artists are constantly being shown and ⅔ of them are dead.

SC: Was there ever a time where you felt like giving up and how did you overcome that obstacle?

JH: Yea, all the time- because I’m doing the work and I have no support from family and famously my mom wasn’t interested in the project until she saw it on the walls in Aperture. All this time I’m making this work I had very little support from my family. She saw me spending a lot of money and a lot of time into this, and was like what about the future? What about 10 years from now? And it’s understandably because it’s hard to see tangibly what is this going to do for you? How are you going to feed yourself? Yeah, there were some very lean years where I had no money and had to put $50 towards an application fee for a grant or exhibition. It cost alot, more than money to make the work and since photography is such an isolated game it can be really depressing and difficult to come out of that. For me what made it a little easier was that I never put an end date on the project. I just knew I wanted to get to specific locations and did months of pre planning to make the connections, talk to the people, see when it is good for them and then fly out and do it. I just told myself that I’m just going to make the work and see where it goes and keep chipping away. There’s no real rush, I just need to keep making the work. By having that in the forefront, that I didn’t have to rush even when other people were asking me about it helped me alot… It was a lot but you have to do what the work commands and that’s what was needed in order for the project to exist.

The year before the pandemic hit, I had to go to LA to make images and I couldn’t wait for any grant money so I went to the bank and took out a loan. I doubled down and bet on myself and was like fuck it, we gotta do it! Told my job that I have to leave for a month and if you have to fire me that’s cool. If not, that’s cool too. And it worked! We got out there and made the images that we needed, came back and got right back to business. Just one of those things where it had to happen then because in a couple months it would’ve been the pandemic and I would have never gotten those images. It was difficult and yea sure I’m exhausted as hell now and mostly tired every single day. The weight of those 9 years are poured into the book and I’m just like I just want some ice tea and cut on the AC and nap.If you don’t ever push through it being difficult the magic might not ever happen.

Semaj is a Brooklyn, NY native. Semaj studied psychology at Trinity College(CT), graduating in May 2018, and received his MFA at Lesley University (Cambridge, MA). Semaj is currently a full- time art educator and coach in Hartford County. Inspired by the works of Gordon Parks, Deanna Lawson, Latoya Ruby Frazier, and Chi Modu, Semaj seeks to reimagine the black gaze through his personal narrative. Semaj challenges the historical prejudices, racism, and false narratives that have haunted the depiction of black figures in society throughout generations. His photographs seek to provide a voice for everyday people who have been oppressed and ultimately discarded out of society’s forefront.

Follow Semaj Campbell on Instagram: @semaj.doc

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photographers on Photographers: Congyu Liu in Conversation with Vân-Nhi NguyễnDecember 8th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Mehrdad Mirzaie in Conversation with Liz CohenSeptember 4th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Elizabeth Hopkins in Conversation with Nicholas MuellnerAugust 21st, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Cléo Sương Mai Richez in Conversation with Shala MillerAugust 20th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Emma Ressel in Conversation with Tanya MarcuseAugust 19th, 2025