Photographers on Photographers: Rosie Clements in conversation with Letha Wilson

I first came across Letha Wilson’s work while reading Charlotte Cotton’s ‘Photography is Magic’ during grad school. The book is a survey of over 80 contemporary photographers whose work contributes to a post-internet conversation about what images mean in an image-saturated world. Letha’s work found me at a time when I was desperate for a sense of community with artists working in the direction I had begun pursuing—merging photography and sculpture. Her spread in ‘Photography is Magic’ captivated me. I was most drawn to her installation of ‘Moon Wave’, a digital print on adhesive vinyl pierced by a column in the gallery where it was documented. The image bends gracefully, stretching from floor to ceiling. Even without being able to witness the piece in person, it was still so arresting that I kept re-opening the page to look at it. Afterward I spent more time with her catalogue of work, where I found piece after piece that inspired me.

I’d like to think there are similarities between Letha and I. We both apply our images to different surfaces to bend, twist, and break them as a way to demand that they become something more. We are both frustrated by the limitations of photography, but also fascinated by the medium.

I’ve been a photographer for most of my life, but I’ve only recently begun to push my images out of the frame, to move them between the virtual and the physical. I’ve always felt a little out of place in the photography community, and have been guilty of having a bit of a chip on my shoulder about it. Letha has been working between photography and sculpture for nearly her entire career. I sincerely hope that my work can be more like hers someday, and hope to adopt some of her sense of confidence, and even pride, in choosing to push the boundaries of her disciplines. It was an honor to speak with her.

Letha Wilson was born in Hawaii, raised in Colorado, and currently works in Taghkanic and Brooklyn, New York. She received her BFA from Syracuse University, and her MFA from Hunter College in New York City. Letha attended the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in 2009, and her artwork has been shown at many venues including Mass MoCA, deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, Bronx Museum of the Arts, The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Columbus Museum of Art, Art in General, Bemis Center for Contemporary Art, and International Center for Photography. Letha’s work has been reviewed in Artforum, Art in America, the New York Times, The New Yorker, among others. Letha has been awarded artist residencies at Yaddo, MacDowell, Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Headlands Center for the Arts, and the Sharpe -Walentas Studio Program, among others. In both 2019 and 2014 Letha was awarded a New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship in Photography. In 2023 Letha had solo exhibitions at the Richard and Dolly Maas Gallery at Purchase College, SUNY, and GRIMM Gallery in London, UK. Letha will have her first institutional solo exhibition at Center for Maine Contemporary Art, Rockland, Maine in September 2024.

Letha Wilson was born in Hawaii, raised in Colorado, and currently works in Taghkanic and Brooklyn, New York. She received her BFA from Syracuse University, and her MFA from Hunter College in New York City. Letha attended the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in 2009, and her artwork has been shown at many venues including Mass MoCA, deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, Bronx Museum of the Arts, The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Columbus Museum of Art, Art in General, Bemis Center for Contemporary Art, and International Center for Photography. Letha’s work has been reviewed in Artforum, Art in America, the New York Times, The New Yorker, among others. Letha has been awarded artist residencies at Yaddo, MacDowell, Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Headlands Center for the Arts, and the Sharpe -Walentas Studio Program, among others. In both 2019 and 2014 Letha was awarded a New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship in Photography. In 2023 Letha had solo exhibitions at the Richard and Dolly Maas Gallery at Purchase College, SUNY, and GRIMM Gallery in London, UK. Letha will have her first institutional solo exhibition at Center for Maine Contemporary Art, Rockland, Maine in September 2024.

Instagram: @letha.wilson

Rosie Clements: When I began grad school at UT Austin in 2022, I was more or less a ‘traditional’ photographer. More recently, I have been embracing my impulse to take digital images and reconstitute them as physical objects.

Your work has been challenging the two-dimensional nature of photography for a long time. Have you always made sculptural images? When did your photos move outside the frame? I see that you have some background in painting, too—can you tell me about the path that led you to where your practice is today?

Letha Wilson: As an undergraduate fine arts student at Syracuse University, I was a painting major. At first I was making somewhat traditional oil paintings, but very quickly I became interested in work that crossed over and defied boundaries — sculpture, painting, collage, and printmaking. I may have made some ‘straight’ photographs very early on, but the picture was always a means to get towards something else. I saw photography as just another visual language, and another material to work with.

I moved to New York City after undergrad, and realized my love for architectural spaces and buildings after being immersed in that cityscape. I learned how to build walls as an artist’s assistant. Some of my first works in grad school at Hunter College were monochromatic rooms one could enter or climb on top of, but I was also photographing these spaces, making Polaroids and cutting them up, so photographs were still a part of my practice. I was mining landscape photos from Colorado, and it wasn’t until the last year of grad school when I decided to literally merge these two ideas together (sculpture and photography) in a series I called photo extrusions.

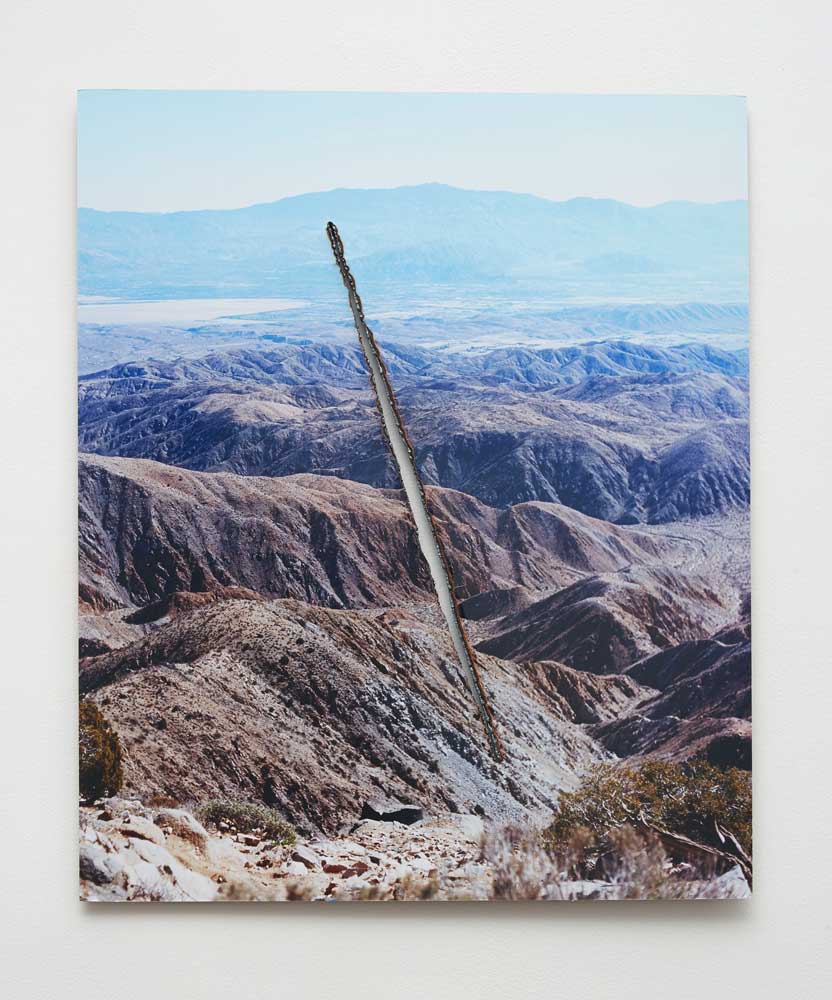

Specifically, I was interested in the landscape as subject matter. I wanted to know if a landscape photo could be contemporary. I wanted to ask what more it could do while picking apart the rules of traditional landscape photography.

RC: It’s interesting to me that you came to photography through these other mediums. It’s the opposite for me—I was a photographer first, and now I’m expanding outside of that discipline.

Why were you drawn to photography, do you think? As a painter and sculptor, how did images first fit into your practice?

LW: I grew up in Colorado, and I think I was inspired by the differences between the natural spaces there in contrast to the urban spaces of New York. I was often working with photos from back home. I have a weird relationship to photography, it’s kind of love/hate. Images can be so beautiful, especially landscape photos, but I’m skeptical of their beauty and the fact that the photographs are not really doing anything in the real world—they’re just kind of sitting there. My practice has always been about that tension between what a photograph can do and what its limitations are.

RC: I really relate to the skepticism you mention, this frustration with pictures and the desire for them to do more. That’s what I’m exploring now in my practice.

In my experience, photography is usually separated out, away from other mediums. I was applying to an open call recently which invited “all artists and photographers” to apply. We are artists! Conversely, I’ve often seen calls that welcome all artists but NOT photographers. I’m often frustrated by this distinction, but I also understand why it is made. I don’t know if it’s accurate to call your practice a criticism of the medium, but I do think it challenges the medium. Do you feel like viewers pick up on that?

LW: Yes, I do think so. I have developed my practice for about two decades now and always had an attachment to and interest in photography, but also been an outsider, because I do not follow the Photo rules and I am actively working against them.

There was a period of time around 2010 or 2011 when blogging had just started and at that point suddenly the Photo community found me. And they seemed to be interested because it was something different. Kim Bourus, who started Higher Pictures Gallery, approached me and I had my first solo exhibition with her. Around this time period it felt like a movement; a lot of artists were working with similar theme, many of us also became friends. We were coming into photography from other mediums and expanding it. Some of these artists had been trained in photography, but many hadn’t. What Charlotte Cotton did with her book ‘Photography is Magic’ really encapsulated that time period.

Even now, do I teach in the photo department or the sculpture department? Do I apply for the photography grant or the fine arts grant? There are pros and cons when you’re straddling two worlds. In my opinion the Photo world is still very conservative. I don’t know if I’ll ever in my lifetime fully be embraced by them, but I think that there’s still a lot of artists that are excited about my way of pushing the parameters.

RC: This movement you mention—pushing the boundaries of the photograph, bending the rules—Do you think that movement has ended?

LW: Perhaps there will always be a struggle within photography: folks that really embrace the tradition of it, and people pushing against that tradition. I don’t think it has to be such a clear dichotomy. As much as I push back on photography traditions, I am clearly entranced by and attached to the medium. I think there’s always going to be some aspect of this ‘battle’ in the medium particularly as photography is used so broadly in our culture from advertising to entertainment, science to fine art, iPhones and text messages; photos are everywhere.

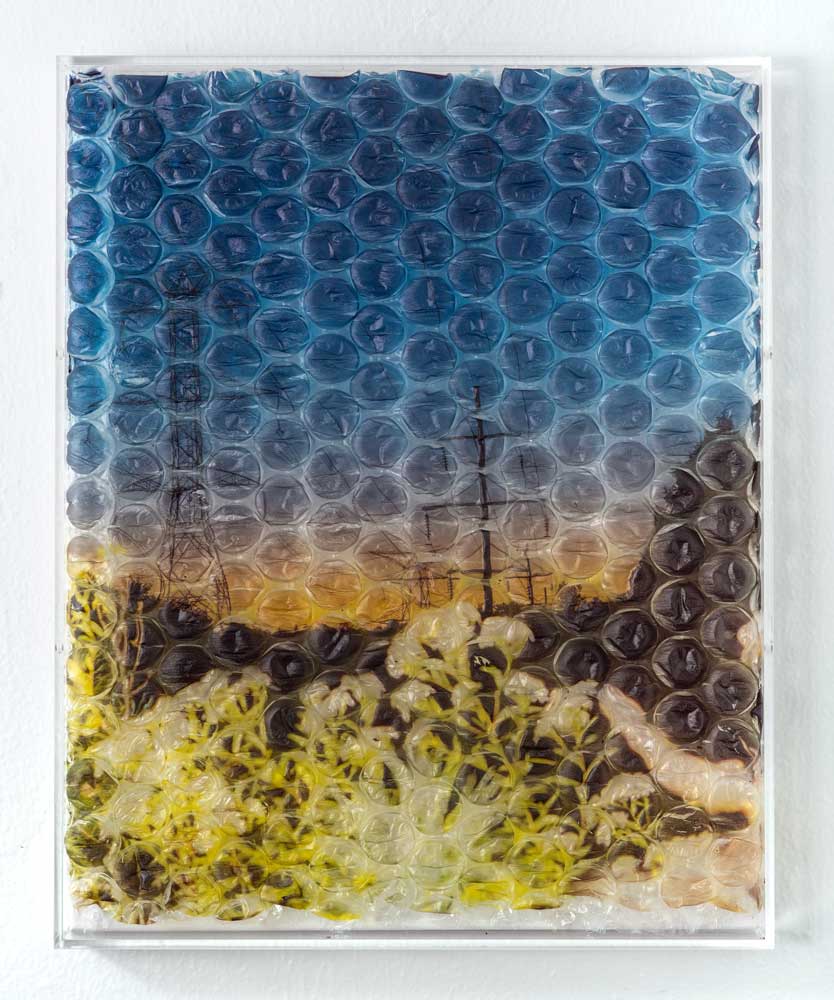

RC: They are. Photographs can now be produced immediately, reproduced infinitely, and seen anywhere at any time, by anyone. The modern photograph—whether shared digitally on social media or printed and hung in a gallery—is part of an expanding visual discourse that I think artists like you are helping to define.

I’m really excited about all of your work, but I’m especially drawn to the pieces that use concrete. Can you explain that process and how you came to it?

LW: When I started printing in the darkroom, I also wanted to hone in my other materials. I was drawn to materials that had a link to the natural world but also the urban environment— 2x4s and lumber or drywall, for example. Concrete also fell into this category and eventually entered my practice in early 2009. I began by simply experimenting with how the material could interact with color C-prints. Once I started combining the materials I found that there was a lot of potential and I really went a deep dive testing possibilities for years. I just followed that path of experimentation. I made hundreds of these works in different ways. I’ve always been, and still am, like a mad scientist: testing, testing, testing.

Because I never spent much time worrying about the technical aspects of photography and I don’t have a lot of the gear, I just use what I can and don’t get caught up in the details. And that kind of not knowing is a really nice layer of…magic, I guess. It supports the beginner’s mind. Working with concrete is similar for me, it is just sort of magical that you can add water to it and the properties completely change.

RC: I love what you said about the beginner’s mind. I really admire how you own the decision not to master the technical aspects of making photos. I’ve always felt kind of sheepish about my disinterest in the technicality and gear involved in photography. Hearing you explain it in this way really changes my perspective, though. Not to disparage those who aspire to fully master their craft—I envy that level of dedication a lot. But I think there’s something really powerful about the choice to remain playful, and connected to the magic of making—whether you’re making a photograph or a sculpture or any other kind of art. What are you working on right now?

LW: Lately in the studio I have been welding and folding photographs UV printed directly onto steel, alongside other metal elements. I have a new series of wall pieces along those lines I will be showing at The Armory Show in a few weeks, a project with Lindberg. I also have a solo exhibition at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art in Rockland, Maine opening on September 29th. I’m making a new artist book for it, which I’m very excited about.

RC: To me, it feels like we’re in a pivotal moment right now with photography, but maybe it’s felt that way for a long time. How do you feel that making images more physical changes the way that we interpret them?

LW: That question is everything to my practice. Many traditional photographers are concerned with the formal and conceptual parts of the image and when the shutter clicks or after the editing – it’s done. For me, that’s where the work begins: after the photograph has been created. The pictures are important to me, of course. They’re tied to my memory and my body because I’ve traveled through all of these places, but I need a physical manifestation in order to translate that real-life experience through a photograph. So I have tried all these ways of picking an picture apart, whether that be the material it’s printed on or the material it’s combined with later.

RC: I can relate so much of what you’re saying. I’ve always felt a bit out of place calling myself a photographer. I’m really not interested in the precision that is so often a cornerstone of picture-making. It’s typically a very traditional medium, and in my own experience, it feels that when you push the boundaries, people are quick to say “well, that’s just not photography anymore.”

LW: For me, that’s fine—so it’s not photography. I do think that in the contemporary art world, they don’t care as much, you know? About defining the medium so specifically. Ideally it is just good art.

There’s definitely people that are interested in my work that enjoy photography, but I think there’s other people that look at it from a sculpture lens, and my practice is really a sculpture practice. I have taken on a huge range of processes in my studio—from prepping digital images for print, sanding and finishing metal, planning and engineering cuts and folds, or welding and pouring concrete. There’s actually a huge amount of math involved. It’s so much more involved in the material world than traditional photography, at least in the studio process.

RC: Do you work with assistants or contract out aspects of your practice? Or is it all you, hands-on?

LW: I really love to be hands-on and do so as much as possible, but as my work has grown in scale, help is often required. In Brooklyn I had more regular studio assistants, maybe 1-2 days a week. Now that I live in upstate NY, my work is much more seasonal, especially now that I’m welding (a skill that I picked up in 2020 to become more hands-on). I have a summer assistant up here so have help seasonally. As far as my large sculptures, those giant steel pieces never come to my studio but are fabricated at a metal shop in Brooklyn, En.Zo. However I am often at their shop bugging them to learn more ! And of course, UV printing, you know, it’s very expensive.

RC: I’m jumping around a little bit, but how do you decide which images to work with? I’m sure that you shoot a lot, and then you develop them in the darkroom and you bring them all out…how do you decide which one you’re going to manipulate?

LW: It’s changed over time. You know, they stopped making Kodak color paper last summer.

RC: Really?

LW: Yeah, completely. I still have maybe a half a roll, it’s probably expired…But I do less and less C-prints now, unfortunately because I do love the darkroom. More and more I’m working with UV printing – I’m really interested in that process.

My overall process is ideally once a year taking a big trip out West and traveling / camping and shooting for a week or more with one analog and one digital camera. After I return I will primarily work with these ‘fresh’ photographs for the next six to nine months. One thing I like about working with photography is that an image changes depending on the day, my mood, or time that has passed. So I have been collecting images over these years, and sometimes go back into my archive and rediscover something. Depending on the project or idea, certain images work. Sometimes the form or material comes first, sometimes the image.

RC: I just finished my MFA in May, and I’d love to know if you have any advice that you would give to someone fresh out of grad school.

LW: Establish your studio practice for yourself. It may involve unlearning some of what you learned in school. It’s a long haul, so don’t feel like you need to figure it out immediately.

Maintain the artist community that you had in grad school and also foster new relationships. I’ve done many ‘studio visit groups’ with like a group of four or five people. Those really help keep you accountable. Maybe meet once a month and even by Zoom if you have to, but something like that is really helpful.

RC: That’s great advice. Thank you.

Oh, one more question—what is your process like to create the source imagery you use? It sounds like you’re a backpacker. Are there any particular locations that you prefer to visit, a particular environment that you like to depict? How do you choose where to go?

LW: I’m clearly drawn to the American West. I like both visiting the big parks and the smaller ones as well. There is something so interesting about them, especially the iconic National Parks like Yellowstone or the Grand Canyon, because of their mythology. These parks live in our collective and cultural memory in a way that is so different from the experience of being there in person. Some of my favorite places are Joshua Tree National Park, Valley of Fire, Goblin Valley, Bryce Canyon, Flat Tops Wilderness and the Badlands. Actually, I don’t really backpack. I just car camp, because I’m almost always traveling by myself, and I try to be safe.

RC: Understandable.

LW: But I still really like camping and road tripping and traveling. Definitely. That was one other suggestion I have for after grad school—try to let your artwork encompass the things you love to do. That was something that I’ve been lucky enough to find.

Rosie Clements was raised in Arizona and currently works in Los Angeles. Her practice spans photography, sculpture, and print. Across all mediums, her practice is fundamentally image-based. In her recent work, she makes digital photographs and reconstitutes them as physical objects, testing the ever-blurring boundaries between the material and the virtual.

Rosie has exhibited her work across the U.S. and internationally, and had her first solo exhibition at McLennon Pen Co. in Austin, TX in 2024. She has been featured on a variety of platforms for visual culture both digitally and in print, including BOOOOOOOM, Southwest Contemporary, and It’s Nice That. She received her BS in Photography from Northern Arizona University and her MFA from the University of Texas at Austin.

Instagram: @_rosieclements

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Rachel Nixon: Art + History Competition Honorable MentionApril 3rd, 2025

-

Photography Educator: Frank LopezMarch 21st, 2025

-

TOP #20 Expanded CyanotypesMarch 18th, 2025

-

Re-molding the Self: Clay Feet, Photographs by Rebecca HorneMarch 5th, 2025

-

Nancy Kaye: Too Many GunshotsMarch 4th, 2025