Atomic Reactions: Photography in the Nuclear Age

November 7, 1946. Admiral W.H.P. Blandy and his wife cut an Operation Crossroads mushroom cloud cake, while Admiral Frank J. Lowry looks on.

Thoughts of nuclear culture have been brought top of mind by Vladimir Putin’s threats to use tactical nuclear weapons, the recent Oppenheimer movie , as well as concern over the discharge of Fukishima reactors’ radioactive wastewater into the Pacific Ocean. This week we plan to share how photography has described the Atomic Age. Today an introduction to photographic archives and images is in order for those who missed the first episode of this drama, the Cold War.

We grew up in America’s atomic age, our childhoods’ filled with both post-war promise and peril. In the late 1970’s our collaboration began with a photographic excursion to New Mexico. It was there we encounter the physical manifestations of nuclear evidence: four Air Force bases, White Sands Missile Range and other weapons test sites, the National Museum of Nuclear Science and History in Albuquerque and the Los Alamos National Laboratory. Military surplus “grave yards,” quonset huts were scattered across the landscape. The New Mexico flag appropriated the giant nuclear reactor of our solar system, the sacred sun symbol of the indigenous Zia people.

Ivy Mike , the world’s first thermonuclear test on November 1, 1952, was considered a post-script to the Atomic Age.

Nuclear Archives. From the beginning of the 2.2 billion dollar Manhattan Project, our government created archival photographic documents and diagrams of every aspect of their scientific and technological achievements. The motivation was to record, justify and disseminate information about this unprecedented “battle of the laboratories.”

60” cyclotron at Berkeley CA Rad Lab, a nod to the scientific- technological collaboration described by President Harry Truman, “The battle of the laboratories held fateful risks for us as well as the battles of the air, land and sea, and we have now won the battle of the laboratories as we have won the other battles.”

Viewing these photographic archives 75 years later, we must consider what may be missing, incongruous or misleading in this trove of images. There is always a political dimension to information—those who control the narrative have the power. Every archive must be viewed with skepticism to determine the conscious or unconscious bias of the creator.

Apparent from the scale of the Manhattan Project, this narrative is far more complicated than that of an elite group of chain-smoking geniuses, working feverishly while sequestered in New Mexico’s mountains. At it’s peak, the Project employed 130,000 workers, many from the surrounding communities . The long term health, social and economics effects on these Americans, the Downwinders , have still not been resolved satisfactorily.

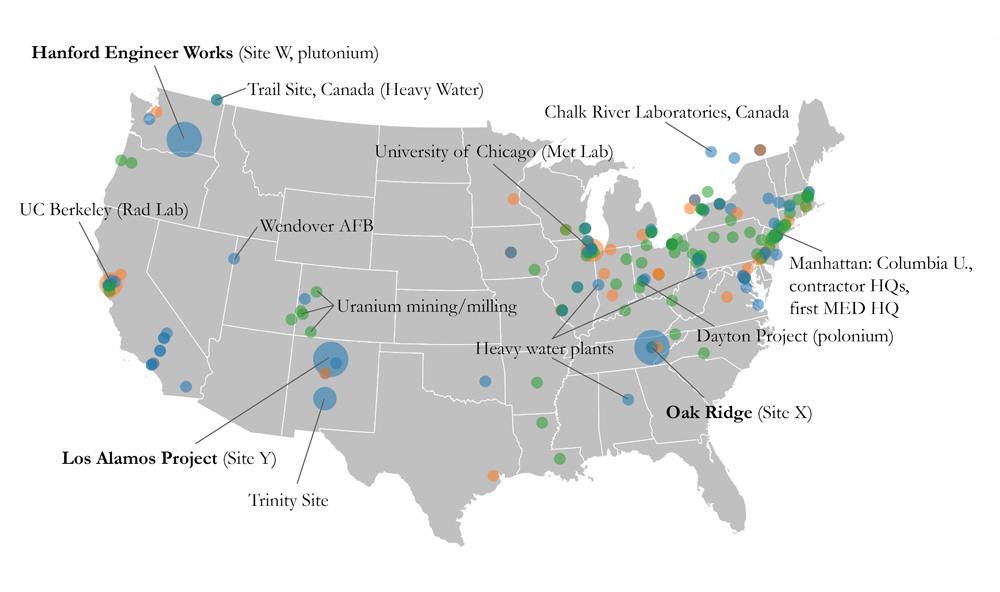

The geographic distribution of the several hundred sites that were operated as part of the Manhattan Project. Blue indicates military or governmental nature; orange indicates educational institutions; green indicates industrial sites and contractors. There are several international sites that do not appear on this map.

Major sites of research, mining and nuclear production criss-crossed the country. To side-step Nuclear Test Ban Treaty requirements, underground testing was even conducted in rural areas of America . What is the atomic legacy in these communities, on the land and water?

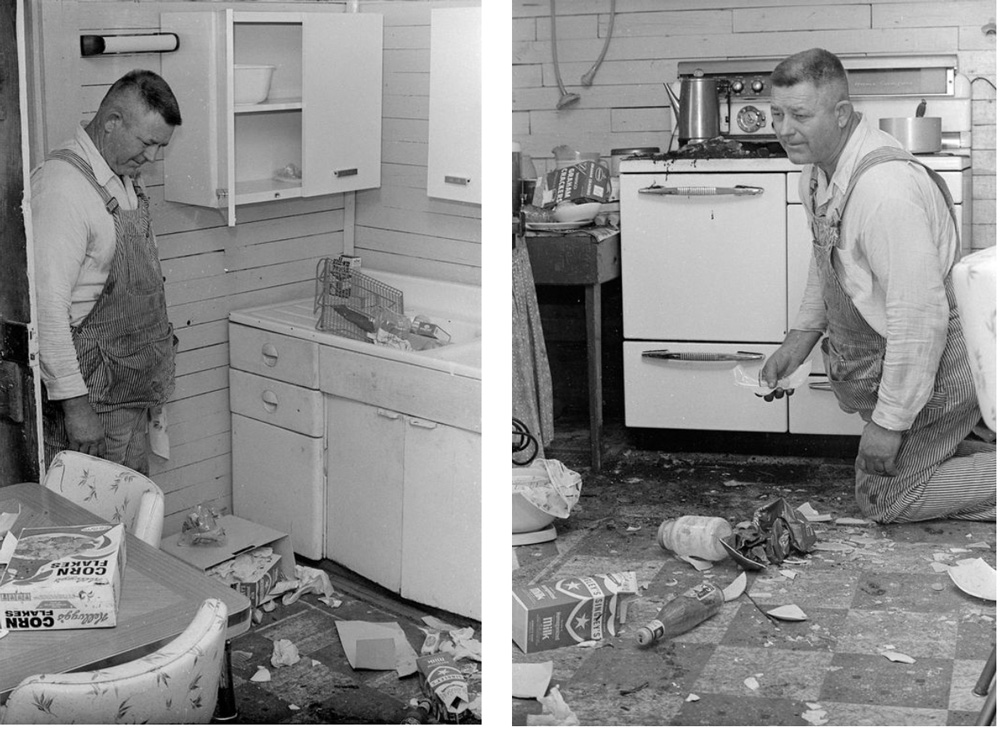

Project Dribble describes two underground nuclear bomb tests exploded under Lamar County, Mississippi. Horace Burge’s home, two miles from the explosion, suffered considerable damage caused by the blast.credit: Moncrief Photograph Collection/MS Dept. Archives and History.

The atomic bomb birthed the Cold War, with global consequences. Military documentation of dramatic test explosions, described a patriotic narrative of American power. Photographic evidence of more problematic

hidden contributions and unintended consequences, were presented as minor inconveniences endured for the greater good.

The July 24, 1946 Baker Test in the initial seconds of the explosion.

Commodore Ben Wyatt’s official request to the Bikini Islanders to leave their atoll for the purpose of nuclear testing.

In an explosion of victory hubris, our government assumed the role of defender of the free world and most Americas remained uncritical, distracted as they raced into the arms of post-War consumer culture.

Beneath the confidence, however, it can not be denied that four years of world war created an undercurrent of paranoia, manifest in the Red Scare and bolstered by the Korean War, creating a mindset we can’t begin to understand—so the arms race advanced across the globe.

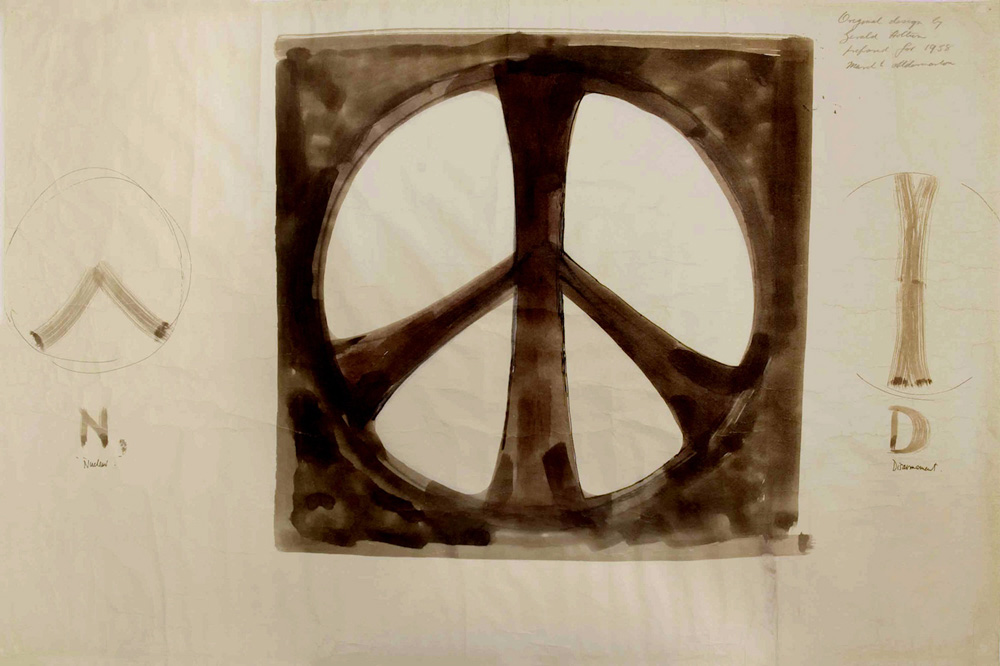

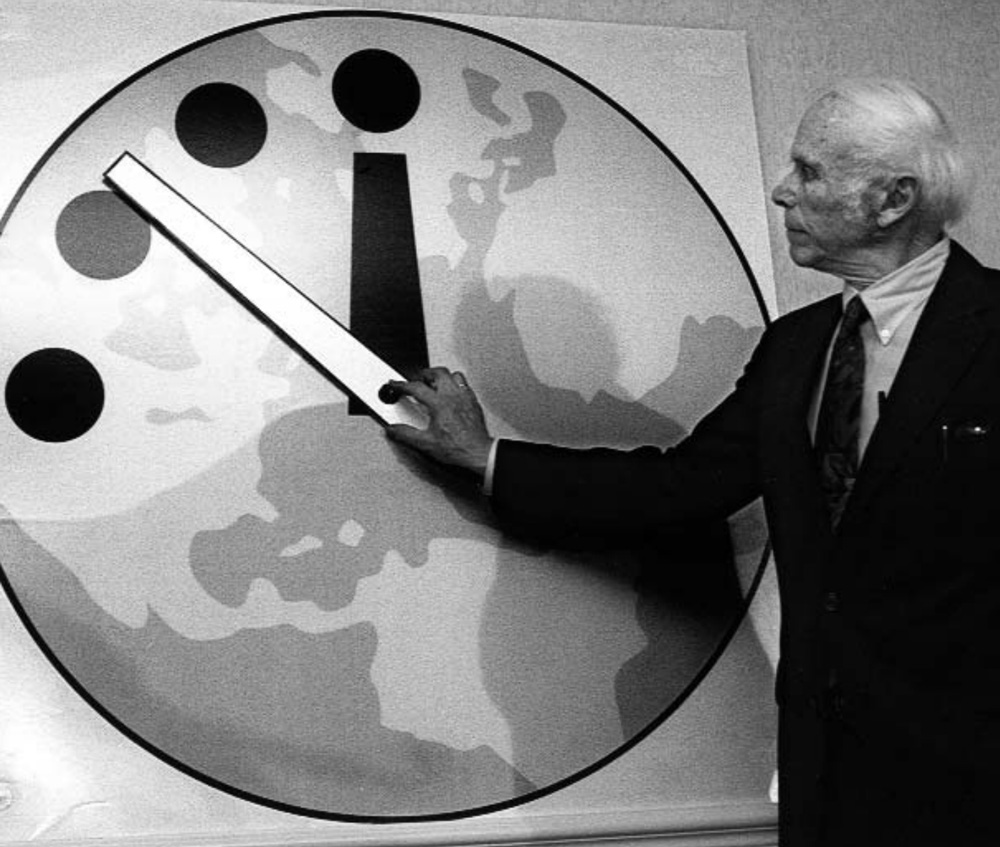

Despite the illusion of safety, concerned photographers and scientists sought out the threats of a nuclear world and attempted to inform the public of its lethal consequences. An analogue clock face became the first symbol of threat devised by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

Ticking began at 7 minutes to midnight, compounding unrestrained threats from across the globe, Today, 76 years later, the hands had moved steadily to 90 seconds before nuclear midnight. credit: Chicago Sun Times.

Photographers captured the aftermath of the atomic bomb bringing critical analysis and international awareness to the dark side of nuclear power. A steady stream of imagery took the form of protest, Atomic Photographers is a visual archive documenting the Japanese bombing and the many subsequent tests, disasters and devastating effects to the environment and local populations around the world.

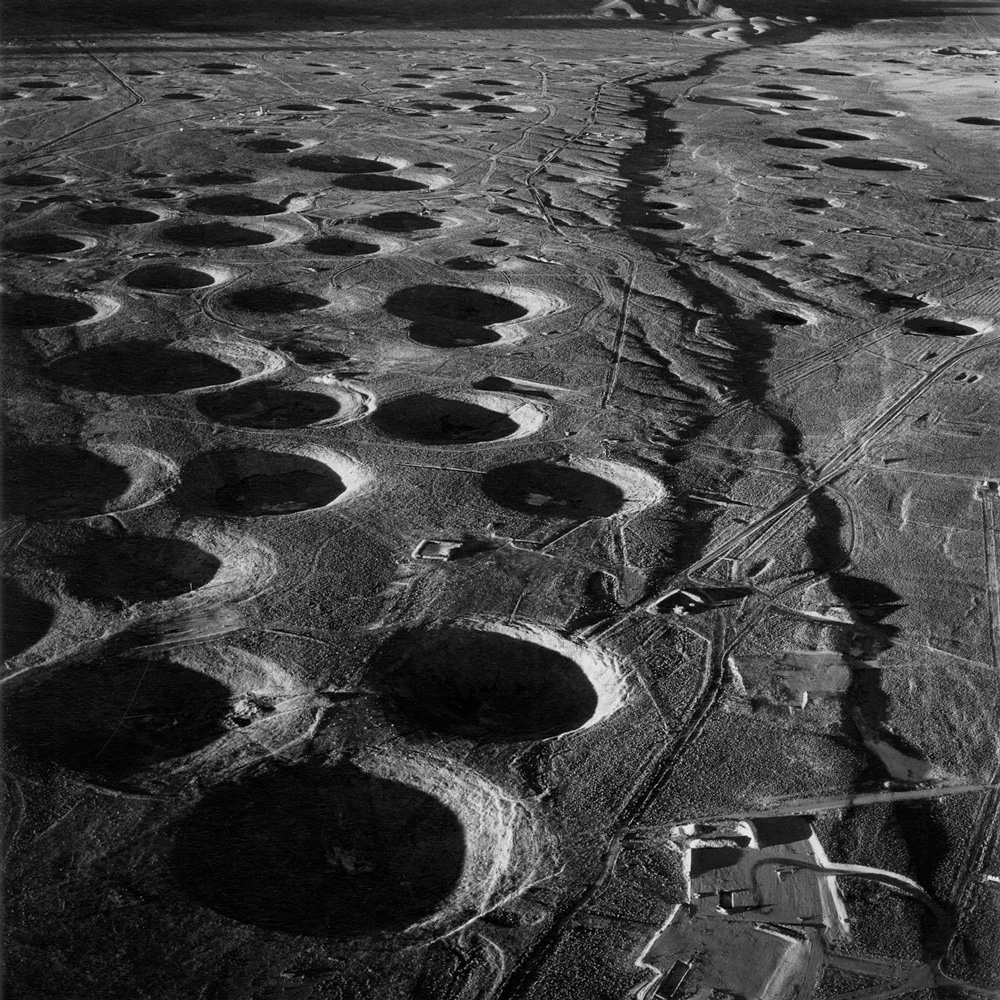

In the 1970’s through the l990’s Emmett Gowin began series of aerial photographs of the landscapes changed by the hand of man. “Subsidence Craters and the Yucca Fault, Looking North on Yucca Flat”, Nevada Test Site, 1996

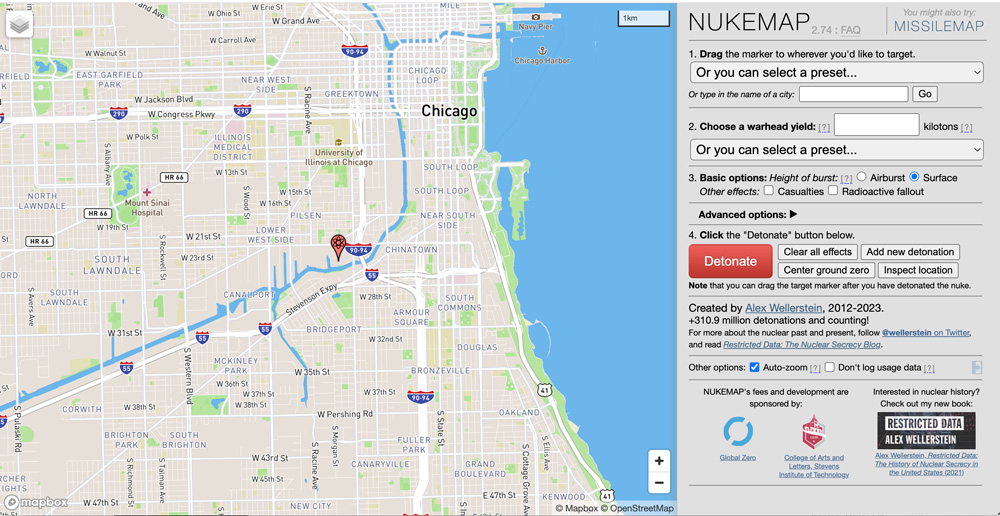

A complex, interactive reminder of nuclear threat has been created by science historian and blogger Alex Wellerstein, the NUKEMAP.

The viewer can choose their favorite target location, kiloton yield and height of blast for maximum destruction. Click the red Detonate button and watch the destruction.

Often the only reaction to overwhelming terror is a nervous laugh and a state of disbelief. We conclude with photographs of atomic kitsch.

Nuclear tests about 75 miles away from Las Vegas in 1953. For twelve years, an average of one bomb every three weeks was detonated, a total of 235 bombs.

Reporters witness the nuclear test on Frenchman Flat , on June 24, 1957. Also known as Area 5, the site was used for above and underground nuclear tests from 1951-1968.

While you’re here: visit Clay Lipsky’s series featured here in 2012. Atomic Overlook re-contextualizes our legacy of atomic tests in order to keep the reality of our post-atomic era fresh and omnipresent.

Barbara Ciurej and Lindsay Lochman are photographic collaborators. As an extension of their long-term examination of the landscape, their new book, BOMBSHELLS , addresses sex and death in the nuclear age.

Instagram: @barbandlindsaycollaborate

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The Favorite Photograph You Took in 2025 Exhibition, Part 2January 1st, 2026

-

The Favorite Photography YOU Took in 2025 Exhibition, Part 3January 1st, 2026

-

The Favorite Photograph YOU Took in 2025, Part 4January 1st, 2026

-

The Favorite Photograph You Took in 2025 Exhibition, Part 5January 1st, 2026

-

The Favorite Photograph You Took in 2025, Part 6January 1st, 2026