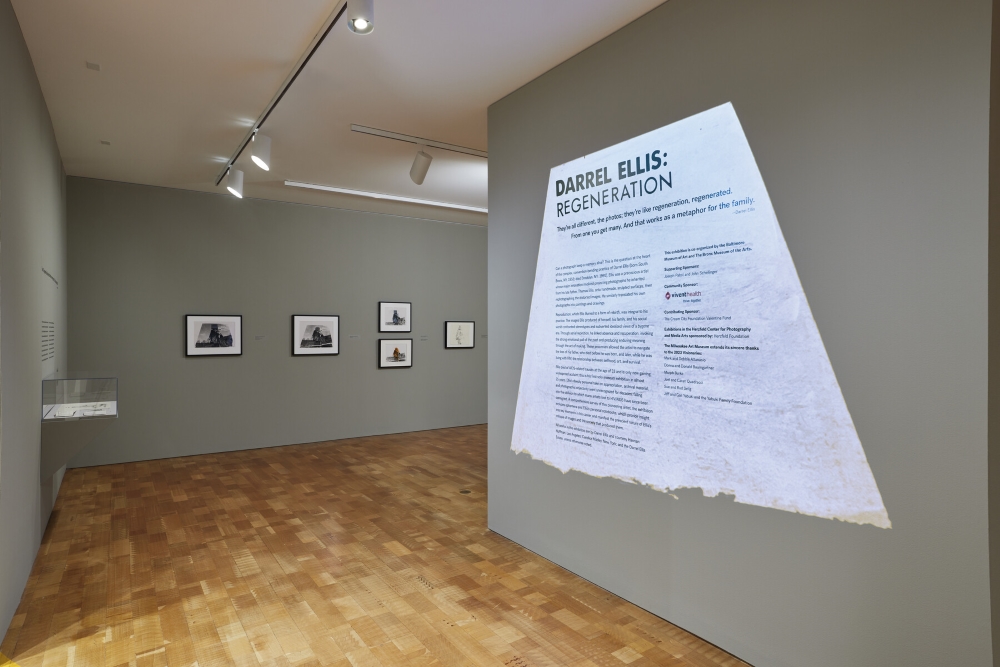

Darrel Ellis: Regeneration explores the breadth of a pioneering practice merging painting, printmaking, and photography

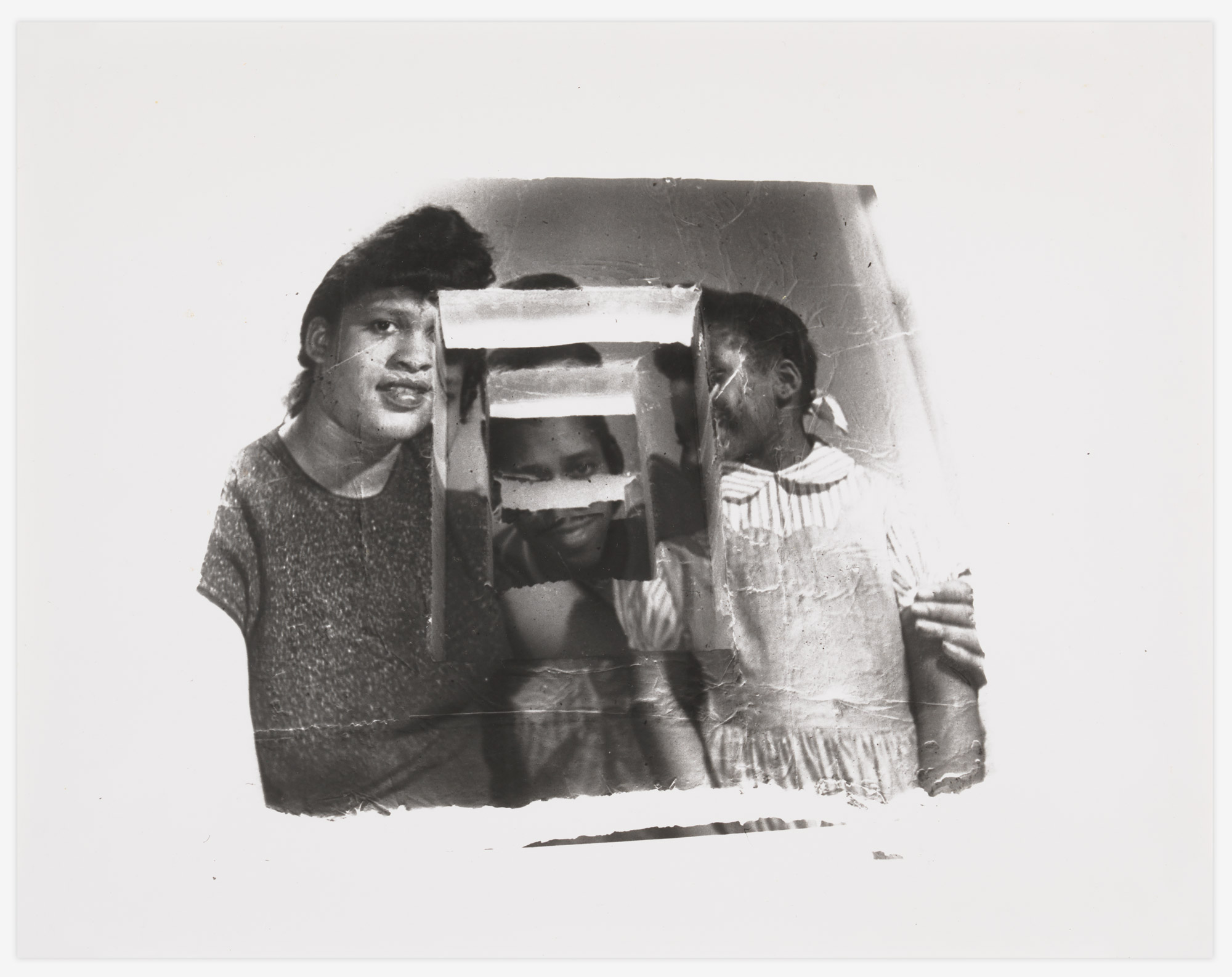

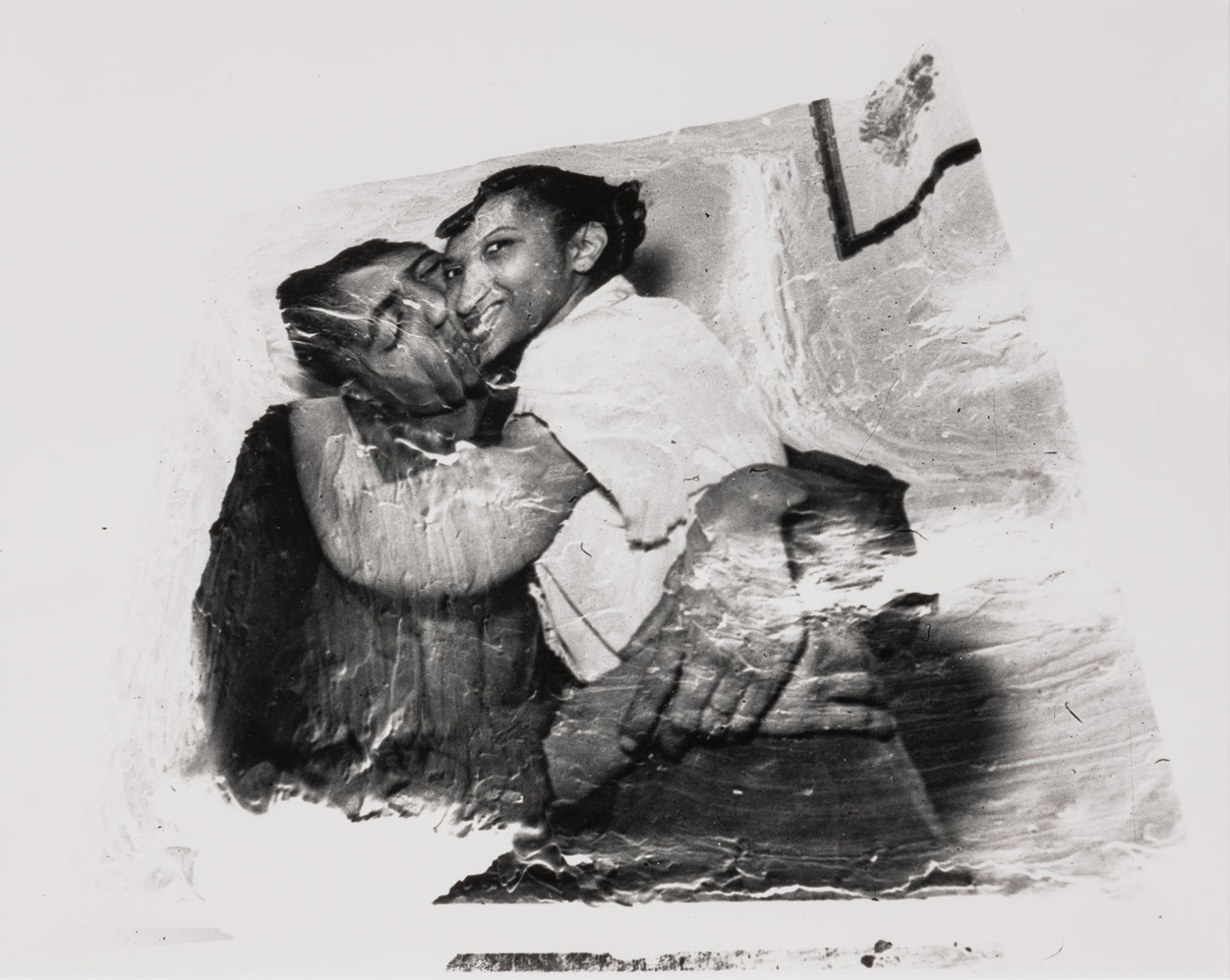

©Darrel Ellis, Untitled (Mother, Father, and Laure), 1990. Gelatin silver print. Private collection, courtesy of OSMOS, New York. © The Darrel Ellis Estate

Currently on view at the Milwaukee Art Museum, Darrel Ellis: Regeneration is the first major museum exhibition showcasing the breadth of Ellis’s practice, which combined photography, painting, printmaking, and drawing. Through his work, Ellis examined themes including domestic life, selfhood, and stereotypes of Black masculinity and anticipated current artistic interest in appropriation, archive, and personal narrative. Co-organized by the Baltimore Museum of Art and The Bronx Museum of the Arts, this expansive presentation features over 120 works and objects that offer an intimate view into the work and practice of an artist whose life and career were cut short by his death from AIDS-related causes at age 33 in 1992.

This exhibition was organized at the Milwaukee Art Museum by Ariel Pate, Assistant Curator of Photography. I asked her to elaborate on her curatorial decisions.

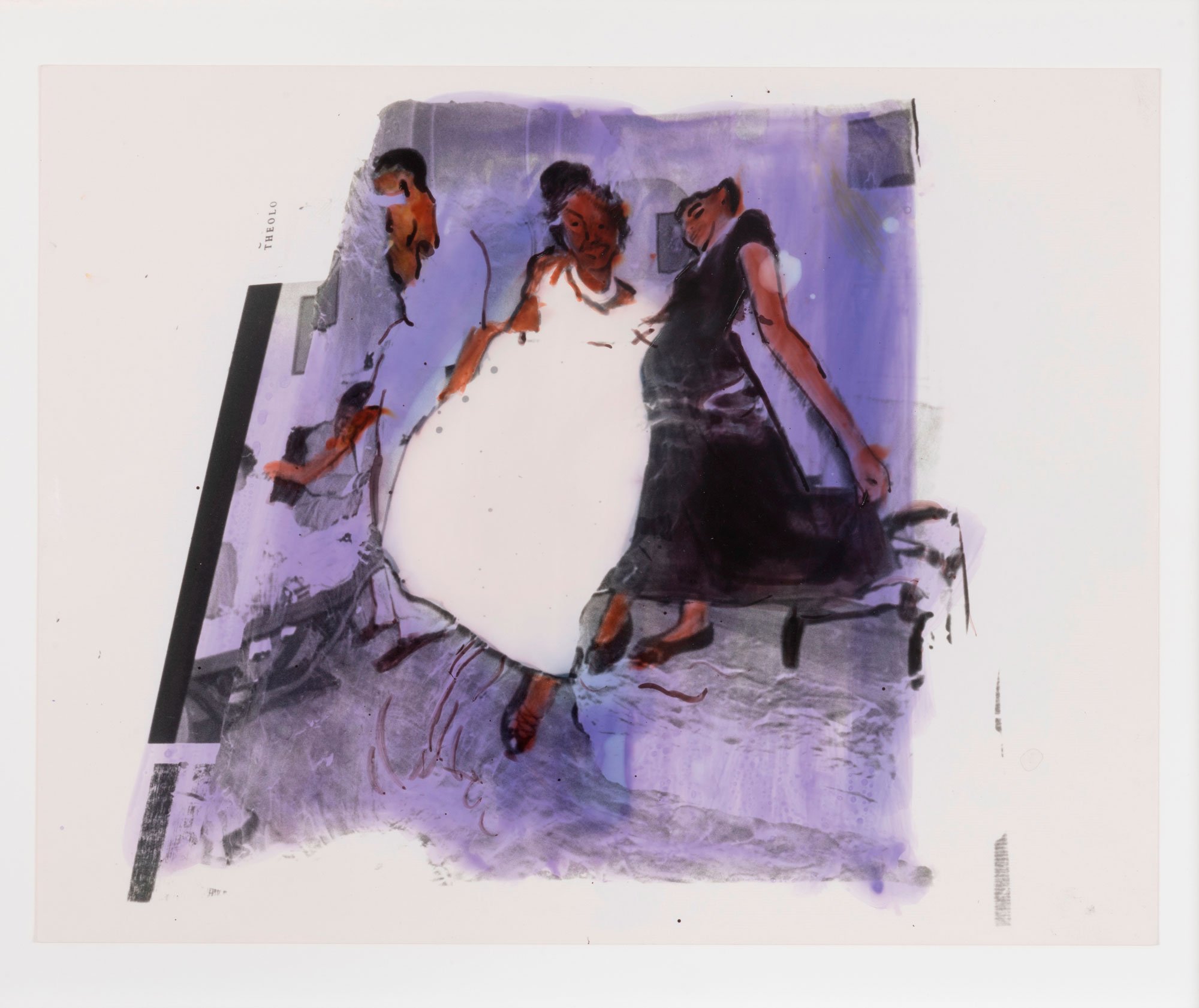

©Darrel Ellis, Untitled (Aunt Lena and Grandmother Lililan Ellis), ca. 1990. Gelatin silver print with colored ink. Collection of Frank Franca, New York. © The Darrel Ellis Estate

Lindsay Lochman: Why did you think this work is important to show at the Milwaukee Art Museum at this time?

Ariel Pate: The exhibition is in our photography galleries—the Herzfeld Center for Photography and Media Arts—and though I don’t think Ellis would have thought of himself as a photographer, his work is intrinsically photographic and leads visitors to reflect on the role and uses of photography in their own lives. Ellis’s work was nearly forgotten because of his untimely death and the overwhelming impact of HIV/AIDS on the art world early in the epidemic. To me, it’s important that museums work to complicate existing art histories, and the presence of Ellis—who was a Black artist interested in exploring figuration and family archives through the language of photography across multiple media—is a compelling counterpoint to the narratives we usually tell about the New York art scene of the 1980s.

©Darrel Ellis, Untitled (Aunt Connie and Uncle Richard) ca. 1989–1991. Gelatin silver print. Private collection. © The Darrel Ellis Estate

LL: Walking through the exhibition, I was impressed with how, despite the fact that a number of works in the exhibition are paintings or drawings, photographic ideas like process, representation, memory, and reproduction are very present. Could you elaborate?

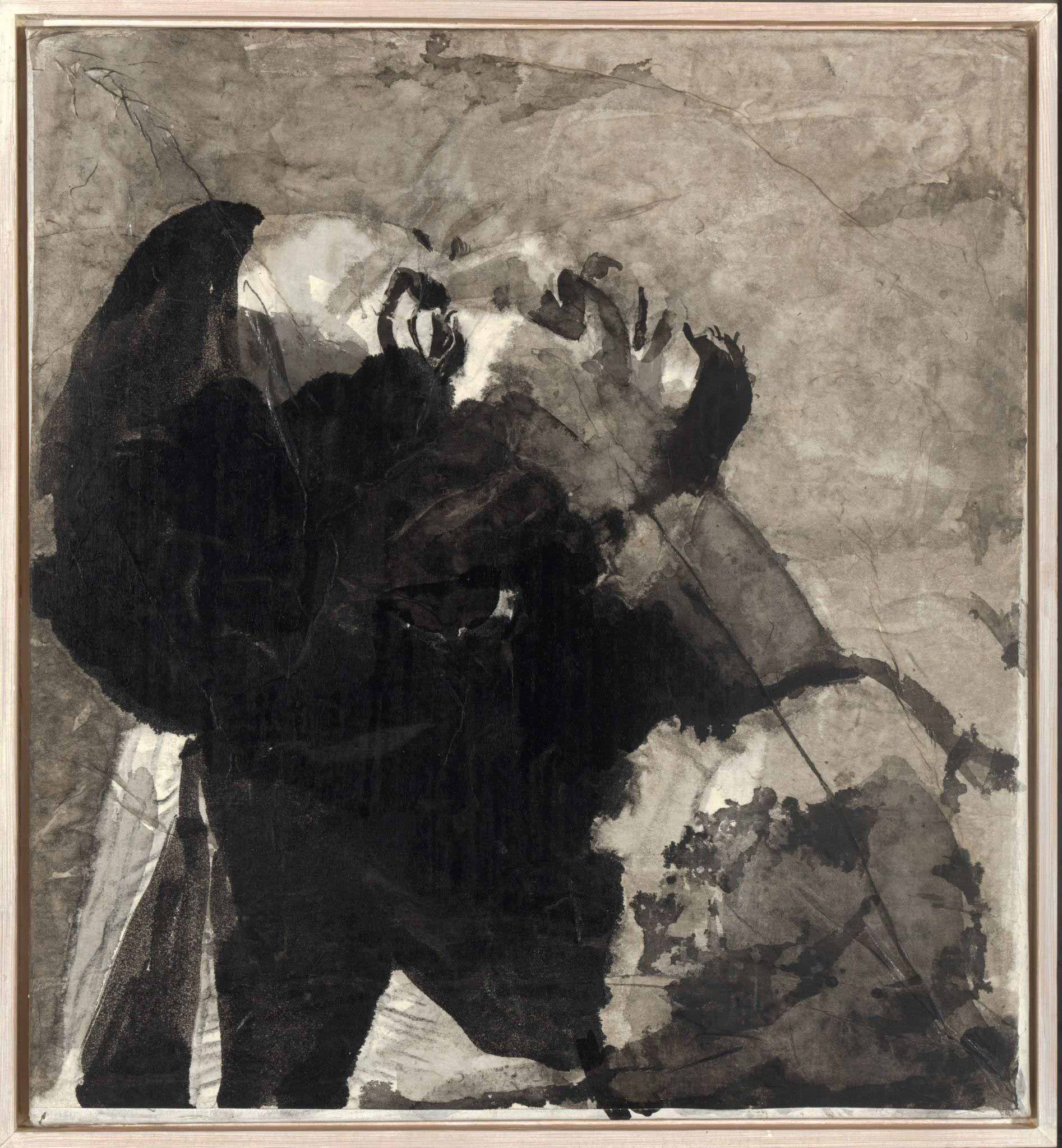

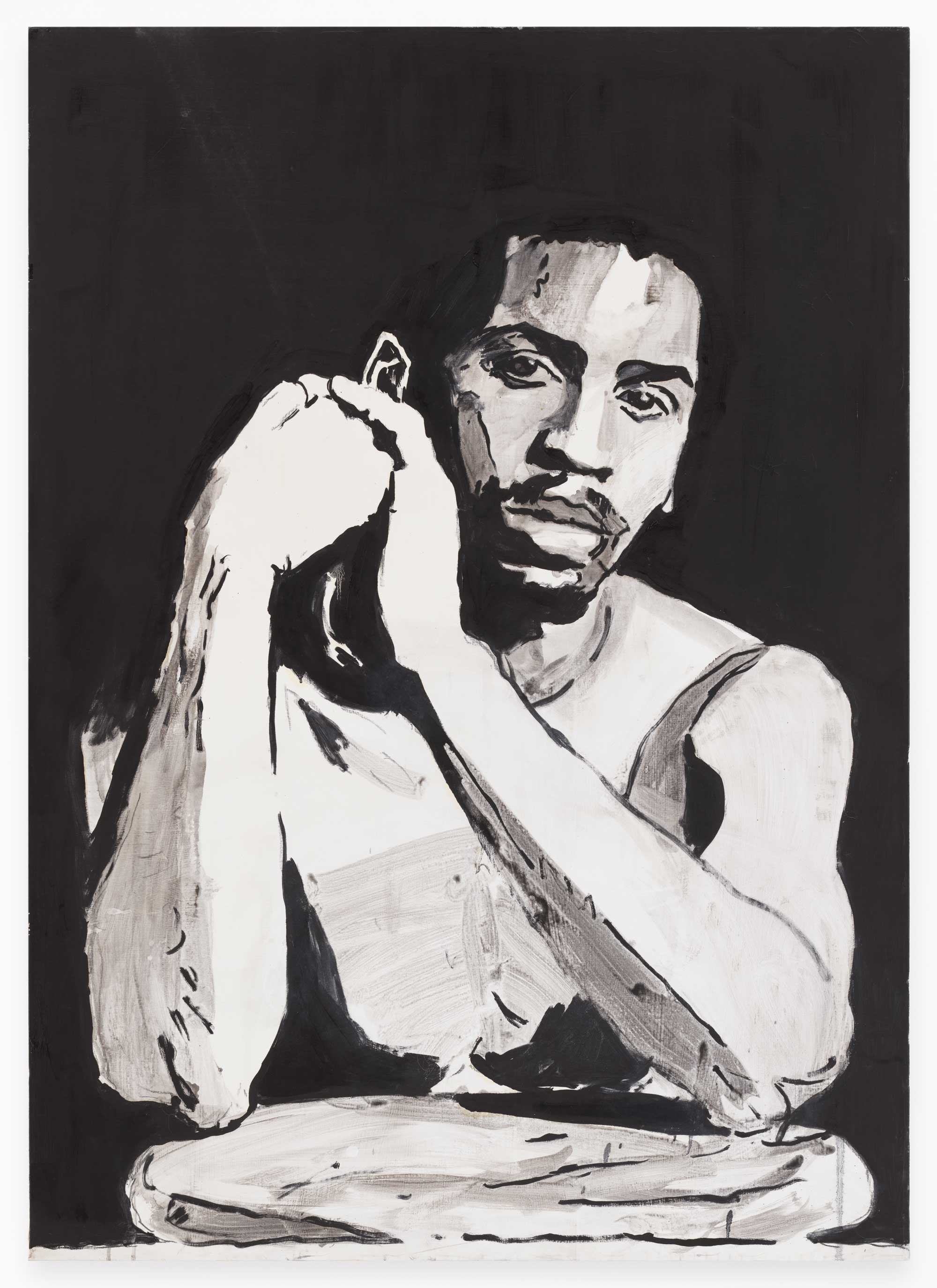

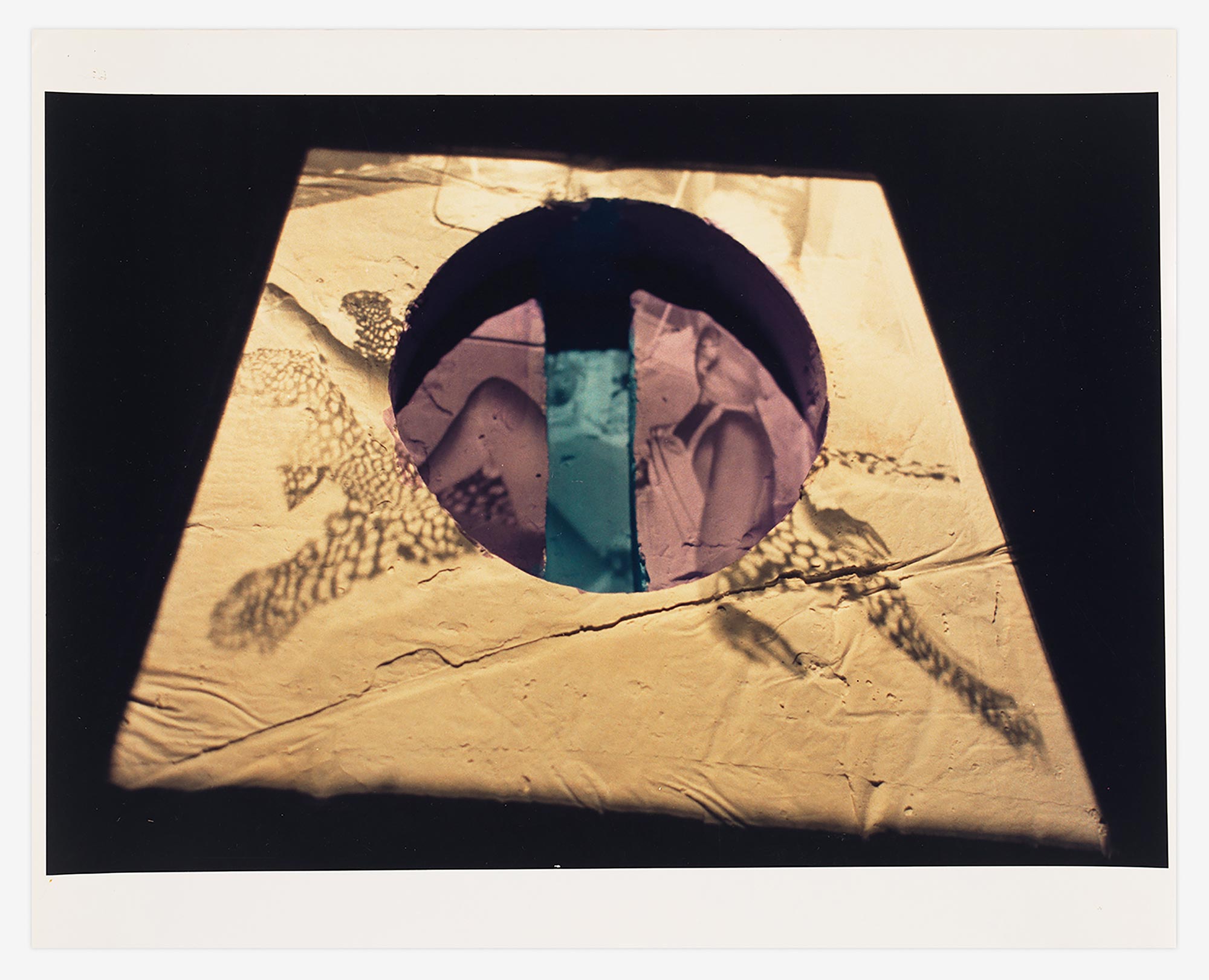

AP: That’s all drawn from Ellis’s own approach. He worked fluently across many mediaand was an amazing draftsperson who drew inspiration from the “great” painters of European art history. His practice frequently centers on the photographic process and the metaphors within it. This shows up in different ways: the series based on his father’s negatives from the 1950s deals with how family photographs become an archive of memory; the painted self-portraits “after” portraits of him by other photographers raise issues of representation and objectification that are intrinsic to the medium of photography. The title of the exhibition, Regeneration, comes from his reflections on his reprinting and distorting his father’s negatives: “They’re all different, the photos; they’re like regeneration, regenerated. From one you get many. And that works as a metaphor for the family.”

©Darrel Ellis, Self-Portrait after Photograph by Peter Hujar, 1989. Brush and black ink and wash over charcoal on Asian-fiber paper mounted on canvas. Baltimore Museum of Art, purchase with exchange funds from the Pearlstone Family Fund and partial gift of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.; BMA 2019.159. © The Darrel Ellis Estate

©Darrel Ellis, Self-Portrait After Photograph by Robert Mapplethorpe, ca. 1989. Acrylic on canvas, 60 in. x 42 in. (152.4 x 106.68 cm.). Glenstone Museum, Potomac, Maryland. © The Darrel Ellis Estate

LL: From early on, Ellis’s practice was driven by his personal experience—narratives around his family, identity, and ambition. How do you see these factors playing out in his work or the exhibition?

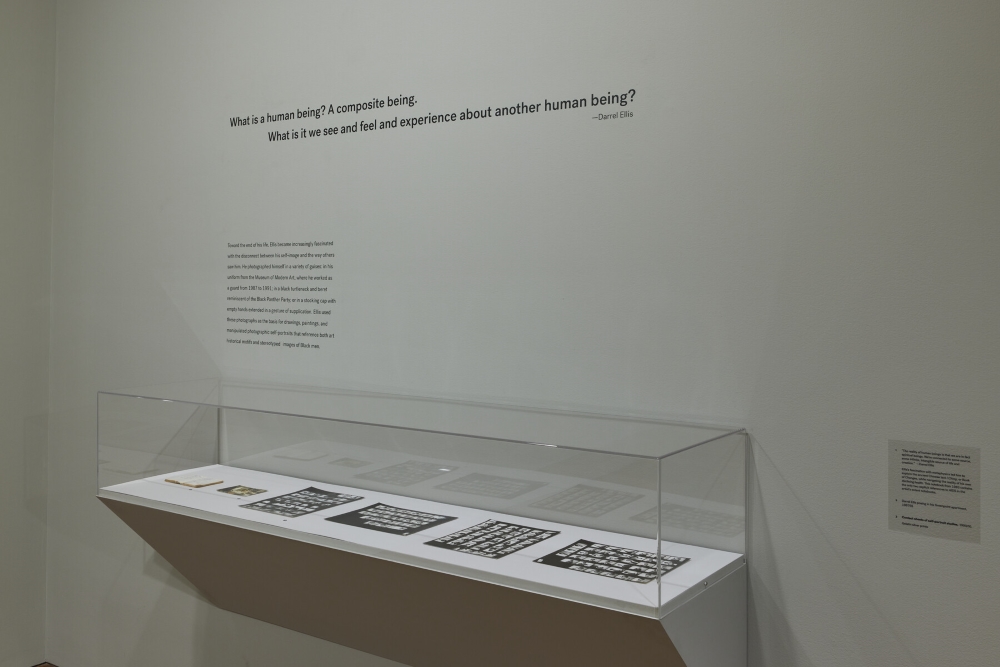

AP: This is really apparent in the works from his father’s negatives. Ellis’s father—a talented photographer and postal clerk—died at 33, two months before Ellis was born, as the result of police brutality. This loss loomed large over the Ellis family. In 1981, Ellis was gifted his father’s negatives by his mother, and they soon became a focal point of his artistic practice. He revisited the images frequently, extracting new meaning and resonances through a diverse studio practice that combined photographic enlargements, drawing, painting, and printmaking. In these works, the family memories embedded within them are labored over, rephotographed, and redrawn by Ellis. Yet they remain inaccessible, distorted images that push and pull the viewer out of a “photographic” reality.

©Darrel Ellis, Untitled (Laure on Easter Sunday) ca. 1989–1991. Gelatin silver print with colored ink. Courtesy of The Darrel Ellis Estate, Hannah Hoffman, Los Angeles, and Candice Madey, New York. © The Darrel Ellis Estate

©Darrel Ellis, Untitled (Laure on Easter Sunday) ca. 1989–1991. Gelatin silver print with colored ink. Courtesy of The Darrel Ellis Estate, Hannah Hoffman, Los Angeles, and Candice Madey, New York. © The Darrel Ellis Estate

LL: How did the exhibition come together?

AP: We are really excited that the Milwaukee Art Museum is the only Midwest venue for Darrel Ellis: Regeneration. Each iteration has been different. Here in Milwaukee, I’ve created a checklist that introduces our audience to Ellis’s work and looks at his process and various series in depth. There’s much we don’t know about Ellis and how he thought about his work, as he died so young, but he left dozens of sketchbooks and notebooks behind. I focused on trying to make him “present” in the exhibition through the notebooks and using quotes from him in the texts as often as possible.

When it was shown at the Baltimore Museum of Art, curated by Dr. Leslie Cozzi, she highlighted Ellis’s place in a lineage with 19th century French painters, like Édouard Vuillard and Pierre Bonnard, in terms of his subject matter and composition. She also worked with a crew of conservators, whose research informed the studio recreation setup in the exhibition here that guides visitors to understand how Ellis created the works. At the Bronx Museum of the Arts, Dr. Sergio Bessa expanded the checklist significantly and focused on Ellis’s place within the New York art scene of the 1980s. Ellis was born in the Bronx and many of the family photographs by his father were taken there, so Bessa celebrated that connection while looking at how Ellis’s artistic and social milieu influenced and inspired him.

LL: How did Ellis get exposed to art, and did he receive any recognition during his lifetime?

AP: Ellis was interested in art from a young age and attended the High School of Fashion Industries in Chelsea in the mid 1970s. As a result, he became an avid visitor of museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where he frequently sketched from old masters paintings in the galleries. After graduating from high school, Ellis devoted himself to being an artist. He shared a studio at PS1 with a friend, and he was accepted into the Whitney’s Independent Study Program in 1981. In 1989, he was invited to take part in Nan Goldin’s landmark exhibition Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing at Artists Space. He was included in New Photography 8, curated by Peter Galassi, in 1992, shortly after his death.

Now Ellis’s work is getting the kind of recognition to which he aspired. This exhibition is the first major museum exhibition of his work, and his work has entered several public collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Whitney Museum of Art, New York; the Studio Museum, Harlem; the Bronx Museum of the Arts; and the Baltimore Museum of Art.

©Darrel Ellis, Untitled (Woman with Leopard Skin), ca. 1988–1991. Chromogenic print. Courtesy of The Darrel Ellis Estate, Hannah Hoffman, Los Angeles, and Candice Madey, New York. © The Darrel Ellis Estate

Darrel Ellis grew up in the Bronx and graduated from High School of Fashion Industries, attended classes at Cooper Union and the School of Visual Arts, and participated in the Whitney Independent Study Program. Throughout his career, Ellis participated in more than 20 group exhibitions in New York and Europe, including the 1989 exhibition Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing organized by Nan Goldin and the touring exhibition The Surrogate Figure: Intercepted Identities in Contemporary Photography organized by the Center for Photography at Woodstock. His work garnered critical acclaim and in 1991, a year before his death, he received a New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship Award. His work was posthumously featured in the Museum of Modern Art’s New Photography 8 exhibition in 1992 and a touring retrospective of Ellis’s work was organized by Allen Frame at Art in General in 1996. While Ellis was an integral member of the downtown New York art scene, it is only now that his work is receiving the depth of study that it truly deserves.

Ariel Pate is the Assistant Curator of Photography at the Milwaukee Art Museum. Since starting in 2016, she has curated collection-based exhibitions, including On Repeat: Serial Photography (2022); Portrait of Milwaukee (2019); and Photographing Nature’s Cathedrals: Carleton E. Watkins, Eadweard Muybridge, and H. H. Bennett (2018), as well as co-curating Shifting Perspectives: Landscape Photographs from the Collection (2022), which was accompanied by an audio guide of community voices, which Pate facilitated. She has been venue curator for touring exhibitions and supported numerous other photography exhibitions, including an extensive virtual tour of Susan Meiselas: Through a Woman’s Lens (2020). She is part of Native Initiatives at the Milwaukee Art Museum, a team of Museum staff and external advisors dedicated to ensuring that Indigenous cultures, resilience, and art are respectfully represented and celebrated throughout the Museum. She previously served as a curatorial assistant in the Department of Photography at the Art Institute of Chicago and received a master’s degree in Curatorial Studies from the Staatliche Hochschule für Bildende Künste Städelschule and J. W. Goethe University, in Frankfurt, Germany.

Barbara Ciurej and Lindsay Lochman are photographic collaborators.

Instagram: @barbandlindsaycollaborate

Darrel Ellis: Regeneration is curated by Dr. Antonio Sergio Bessa, chief curator emeritus at The Bronx Museum of the Arts, and Leslie Cozzi, curator of prints, drawings, and photographs at the Baltimore Museum of Art. Additional research was provided by Bronx Museum Curatorial Fellow Kyle Croft.

Exhibition Sponsors:

Supporting Sponsors Joseph Pabst and John Schellinger

Contributing Sponsor The Cream City Foundation Valentine Fund

Exhibitions in the Herzfeld Center for Photography and Media Arts are sponsored by Herzfeld Foundation

The Milwaukee Art Museum extends its sincere thanks to the 2023 Visionaries.

Mark and Debbie Attanasio, Donna and Donald Baumgartner, Murph Burke, Joel and Caran Quadracci, Sue and Bud Selig, Jeff and Gail Yabuki and the Yabuki Family Foundation

For more information, visit mam.org.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Broad Strokes III: Joan Haseltine: The Girl Who Escaped and Other StoriesMarch 9th, 2024

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Wishmaker and The Landau GalleryFebruary 27th, 2024

-

Janna Ireland: True Story IndexFebruary 17th, 2024

-

Richard McCabe: PerdidoJanuary 7th, 2024

-

Aline Smithson: The Ephemeral ArchiveJanuary 5th, 2024