Mexican Week: Emilio Rojas — Part I

Emilio Rojas and I crossed paths two years ago while living in New York’s Hudson Valley. At that time, he was preparing for a public art exhibit and talk titled Decolonial Aesthetics as part of The Hudson Eye. The profound insights Emilio shared about navigating a career in the arts as an immigrant resonated deeply with me. As fellow photo-based visual artists from Latin America, both of us confronted, although quite differently, the intricate dynamics of U.S. migration. Our meeting proved to be a profoundly enriching experience that prompted me to reassess and redefine my own artistic plans and aspirations.

While our time was short and sweet, he later sent me a copy of his beautiful catalogue, tracing to wound through my body (Lafayette College, 2021), marking his first comprehensive survey of work. The exhibition traveled to 4 different institutions, and spanned a decade of live performances and interventions, capturing various mediums such as video, ephemera, photography, sculpture, installation, and poetry. Since then, I have become an avid admirer of Rojas’ practice, where the camera serves as one of the many connecting dots in his wide and bright constellation of highly conceptual approaches and techniques.

Rojas’ work, emotive and expansive, draws attention to the deep scars of colonialism and systemic violence that run deep in the open veins of Latin America. As the last installment of our editorial week on contemporary Mexican photography, Rojas and I discuss his enduring relationship with photography, from his formative experiences in darkrooms to its ongoing significance in his interdisciplinary practice through projects like Instructions for Becoming, Naturalized Borders (To Gloria), and GO BACK TO WHERE YOU COME FROM.

On display today at Centro de la Imágen, CDMX, at 2:30 pm and at Clavo Art Fair from Feb. 9 – 11, Rojas will be presenting his stop-motion animation project, El Retorno. Created from 15,000 looped photographs of the artist rolling through the streets of Santander, Spain, the project symbolizes a profound quest for identity and belonging, particularly within the context of returning home from the motherland and the ongoing struggle of diasporic experiences.

—Vicente Isaías

Latin American Editor

Emilio Rojas is a multidisciplinary artist working primarily with the body in performance, using video, photography, installation, public interventions, and sculpture. He holds an M.F.A. in Performance from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a B.F.A. in Film from Emily Carr University in Vancouver, Canada. As a queer, Latinx immigrant with Indigenous heritage, it is essential to his practice to engage in the postcolonial ethical imperative to uncover, investigate, and make visible and audible undervalued or disparaged sites of knowledge, narratives, and individuals. He utilizes his body in a political and critical way, as an instrument to unearth removed traumas, embodied forms of decolonization, migration, and poetics of space. His research-based practice is heavily influenced by queer and feminist archives, border politics, botanical colonialism, and defaced monuments.

His work has been exhibited in exhibitions and festivals in the U.S., Mexico, Canada, Japan, Austria, England, Greece, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Holland, Colombia, and Australia, as well as institutions such as The Art Institute and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, Ex-Teresa Arte Actual Museum and Museo Tamayo in Mexico City, The Vancouver Art Gallery, The Surrey Art Gallery, The DePaul Art Museum, SECCA, the Syracuse University Museum of Art, The Johnson Museum of Art and The Botin Foundation. From 2019-2022 Rojas was a Visiting Artist in Residency in the Theater and Performance Department at Bard College in New York. He has taught in the M.F.A. programs at Parsons the New School and the low-res M.F.A. programs at PNCA in Portland, Oregon, and University of the Arts, in Philadelphia. He is currently a visiting full-time professor at Cornell University in the School of Art, Architecture and Planning. His a traveling survey exhibition Tracing A Wound Through My Body accompanied with a bilingual catalogue, is currently exhibited in its third iteration at the Usdan Gallery at Bennington College in Vermont, to continue at SECCA, North Carolina, and Artspace, New Heaven.

Follow Emilio Rojas on Instagram: @performanceroarte

Website: emiliorojas.studio

Vicente Cayuela: Emilio, I’ve been meaning to interview you for almost two years! I am so glad we finally got the chance to collaborate. You mention that, over the years, your work has become less about your body and more about the collective body. How has this change found its way in your visual language and the practices you employ for art-making?

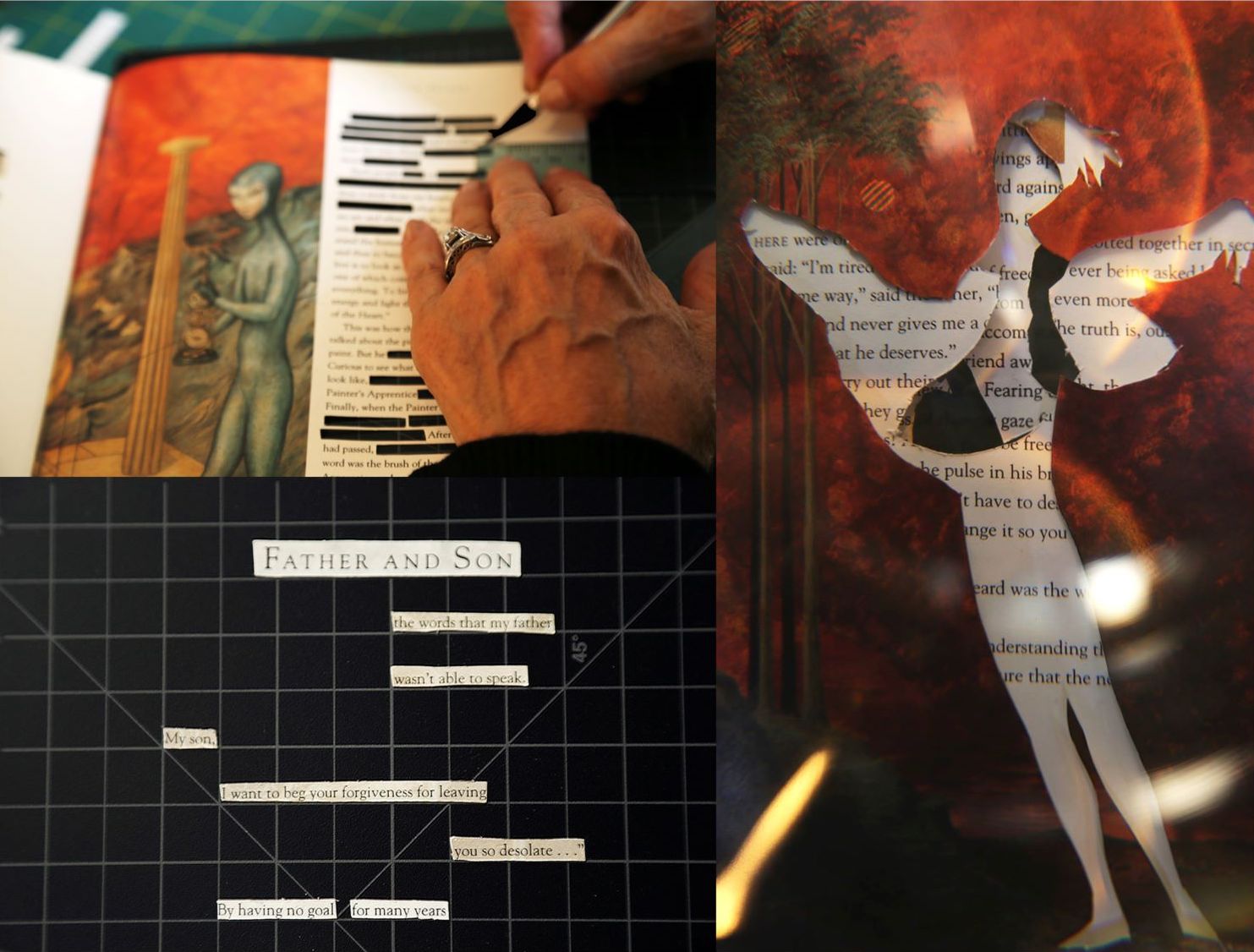

ER: I think it goes back and forth, I work at the same time in several projects that are ongoing and also collaborations. There are some works that are deeply personal and involve my own biography like Manual To Be My Own Father, where I’m re-writing a book that my father wrote in 1982 by cutting it word by word and creating a new text, which I’ve been working with since 2015.

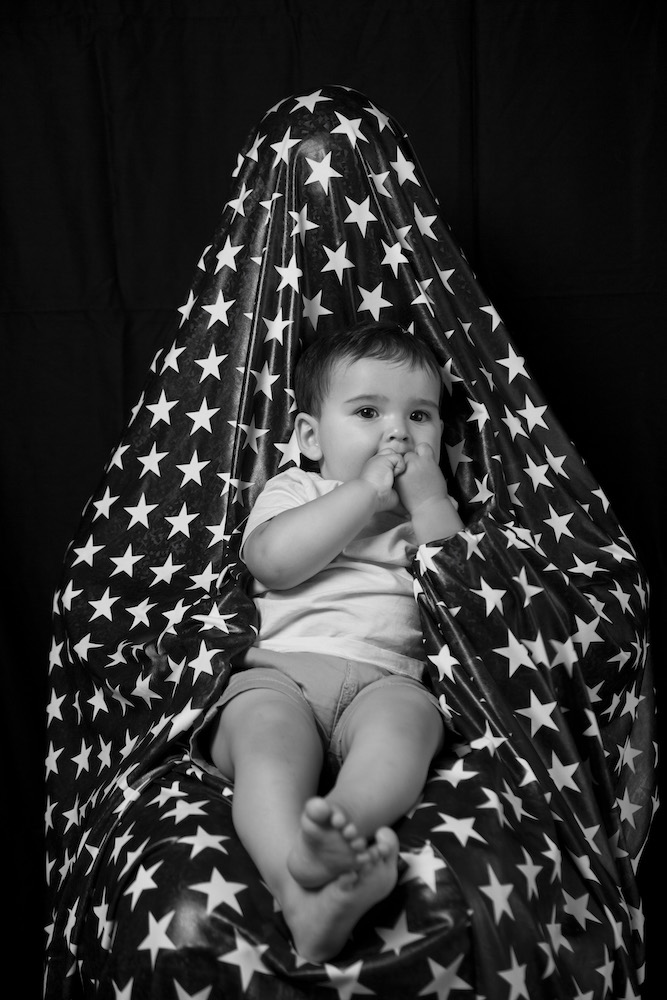

But there are also works like m(Other)s, which started 2017, working with undocumented migrant mothers and their first generation children where my body is not even present in the work. In the videos, the m(Other)s are covered by a fabric with the stars of the American Flag, creating a ghostly image that both references the historical hidden mother photography and protects their identity.

These portraits seek to connect the political and social situation of women at the turn of the 20th century with the invisibility of the labor of immigrant women today. Although I am a migrant in the United States, my experience is very different from these mothers, and the intention of the work is to amplify their voices.

I’ve also been working with the archive of chicana feminist writer Gloria Anzaldua for over ten years, and every year I feel that I find different ways to relate to the archive. Ultimately I only have my body as a vehicle to access the collective body.

VC: What is something that you learned when you began working on socially-engaged practices that you hadn’t thought of before in your art-making processes?

ER: I’ve learned that socially engaged practices are messy, and porous, when you are making work by yourself you get to make all the aesthetic and practical decisions alone. When I’m performing by myself, I know the limits of my body, and what I’m capable of doing, especially with durational performance. When you are working in communities, you have to build trust, you have to listen to your collaborators, you have to make decisions together, to listen to their expertise on the site, it’s a much more democratic process, and it takes time, and care. I cannot ask for the same rigor I ask for myself in my work. I know I can perform for 12 or 24 hours without stopping, but when I choreograph a group performance, I have to consider the capacity of the entire group, their limitations, their expectations, their fears. I learned a lot from one of my mentors, Ernesto Pujol, who calls himself a social choreographer. To work with more people has a lot of more ethical and practical considerations.

©Emilio Rojas, Naturalized Borders (To Gloria). Courtesy the artist.

VC: Can you expand these ideas thinking about one of your many community-engaged, site-specific projects?

ER: For example, Naturalized Borders (To Gloria), was a land art and community-based project, which included a 100-footlong (30 meter) line of indigenous crops. This land art installation was in the shape of the US-Mexican border and was planted with corn, squash, and beans (the three sisters) … on the ancestral homelands of the Muhheaconneok or Mohican people.

[The project] was created for the Live Arts Biennale at Bard college in collaboration with the Bard farm, students and community members. When the installation had grown through the summer, and students had come back to school, I developed workshops, exercises and community events to reimagine and embody our own relationship to the border.

The most important things I learned was to trust my collaborators, and to be open to the unknown, a social practice work is a process where you might know where you begin, but you have to let the journey guide you and not to impose your aesthetic vision or agenda into a project but to co-create with and for the community and not without and about them. Continuing the legacy of Anzaldúa, the work attempted to unearth histories of immigration, labor rights, borders, land sovereignty, and systemic oppression.

©Emilio Rojas, Tracing a Wound Through my Body, Usdan Gallery, Bennington College, 2023, installation shot. Courtesy the artist, photo by ©Alon Koppel Photography

VC: You must develop very deep bonds with the people you work with, considering the span of your works and how involved you become in the community.

ER: [Although] this commission began as an invitation to create a new work and visit for a couple of months, [it became] a year-long project with multiple visits.

I eventually ended up teaching at Bard College for 3 years and moved to Hudson valley. My main collaborator, Rebecca Yoshino, the Bard manager, became one of my best friends and we worked on other projects together.

I like the idea of art as a megaphone you are able to pass around to amplify what people in your communities have to say, and also to find your own voice. As pedagogy, it is also a tool you can teach others to use, then they can pass it to others. When I work with communities, whether it’s immigrants, mothers, agricultural workers, queer folks, BIPOC, refugees, dancers, indigenous peoples, I think of building empathic bridges that strengthen our bonds of solidarity and allyship with one another. Anzaldua used to close her letters, instead of with “sincerely,” “Contigo en la lucha,” which translates to “with you in the struggle.”

VC: Poetry holds a significant place in your creative language. How can performance be viewed as a manifestation of embodied poetry? How do these mediums compliment or are at odds with each other in your work?

ER: I feel performance is embodied poetry, is a way of making meaning with the body, to enflesh metaphor through action. Poetry and performance work together in my practice, to the point where I don’t think one can exist anymore without the other.

I write poetry to process performances, and I also read poetry every day and is one of my biggest sources of inspiration. I think about the way Audre Lorde wrote about poetry as a keystone to the survival of marginalized identities, she writes: “poetry is not a luxury. It is a vital necessity of our existence. It forms the quality of the light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams toward survival and change, first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action.”

For me, language helps me turn my ideas into action, into movement, into gesture. There is an economy of language in poetry that requires a deep knowledge of ourselves, the world we live in, and our experiences, just as there is an economy of gesture in performance that requires radical vulnerability and discipline. Writing and performance are two passions that require discipline, and devotion.

I’ve been writing for as long as I can remember, but for many decades those poems and texts were never shared. Now they are a fundamental part of my practice, often published alongside the photographs, read with different voices in my videos, and more recently made into vinyl text for my exhibitions.

My collaborations with poets like Natalia Toledo, Pamela Sneed, and Sibani Sen have been pivotal in my life and practice. My father, who abandoned my family, is also a writer so I tried to stay away from writing for many years. It wasn’t until I began working with his book, in the piece Manual To Be My Own Father, that I was able to share my poetry with an audience.

In this work, I cut my father’s best-selling book, Pequeño Hombre, (published in 1984 and translated to English as Little Friend in 1990) word by word with an X-acto knife to create my own poetry. It was the words that my father had written more than twenty years ago that gave me permission to explore writing more freely and for poetry to become an integral part of my work and process.

This piece was my MFA thesis at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and since then poetry and performance began a conversation that I hope will continue for the rest of my life.

©Emilio Rojas, Manual To Be (To Kill) or To Forgive My Own Father, 205–ongoing, stills from performance, 2016. Courtesy the artist.

VC: You mentioned that activism shifted your practice from being outcome-oriented to being process-oriented. Thinking about the current state of the world today, how can the arts—seen as both an emancipatory tool and process rather than a product of consumption—guide us toward justice and, ultimately, freedom?

ER: This is a very heavy question, which I’ve been asking myself a lot since the pandemic, and also in the past few months with the atrocities we have witnessed in Gaza. What is the role of the artist in all of this chaos? I often think of the words of civil rights activist Bayard Rustin, who once said in a speech “The only weapon that we have is our bodies, and we need to tuck them into places so wheels don’t turn.”

I often think of performance as the practice of tucking our bodies into those uncomfortable places that challenge the status quo and the construction of hegemonic narratives that tend to exclude us. It is not a product for consumption but a place of resistance, and resilience. I come from also being an immigration activist, and from being mentored by artists like Tania Bruguera, whose work she defines as artivism.

For me art is a tool for collective and personal emancipation. The Merriam-Webster definition of the word emancipation is: to free from restraint, control, or the power of another, its roots come from the latin emancipatus to “set free from control.” Art has the potential to ask the questions, to shift paradigms, to build bridges. Gloria Anzaldua writes: “my job as an artist is to bear witness to what haunts us, to step back and attempt to see the pattern in the events (personal and societal) and how we can repair el daño (the damage) by using the imagination and its visions. I believe in the transformative power and medicine of art.” The medicine of art not only reaches the spectator or participant, it is also a balm for the artist in the process of making it, of imagining a future where our voices are heard and valued.

©Emilio Rojas, GO BACK TO WHERE YOU CAME FROM (Santa María Llena Eres de Gracia), 2018. Courtesy the artist. “In 2015 I began a series of research projects and performances centered around Christopher Columbus as a symbol of European imperialism and white supremacy, and the lasting impact of his “discovery” of the Americas. For GO BACK TO WHERE YOU CAME FROM (Santa Maria) , I traveled to the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Portugal, France and Spain with the replica of the boat La Santa Maria. Wearing a jumpsuit with embroidered letters spelling the titular phrase, I navigated public spaces while carrying the boat for 2 months and 9 days, The performance concludes with the return of Columbus’s boat to the Atlantic Ocean in the exact location where Columbus departed in 1492, suggesting the closing of a circle and completion of a journey.”

©Emilio Rojas, GO BACK TO WHERE YOU CAME FROM (Santa María Llena Eres de Gracia), 2018. Courtesy the artist.

VC: This emancipatory vision also permeates your vision as an educator as a professor at Cornell University. Can you tell us more about the philosophies inside your classroom?

ER: I’ve been teaching for a decade now at many different institutions and my pedagogy has changed through the years. I had great teachers and mentors like Ernesto Pujol, Tania Bruguera, Lin Hixson, Anne Hamilton, Guillermo Gomez Peña and Roberto Sifuentes, Marylin Arsem, Pamela Sneed, Tacita Dean and Robin Deacon. Each of them had different kinds of pedagogy, but the one thing that they all had in common was a generosity of spirit and sharing their experience, knowledge, resources, and their own creative process. From each of them I took pieces of their pedagogy which I now pass on to my students. I think of bell hooks writing on her book Teaching to Transgress: “The classroom remains the most radical space of possibility in the academy…Urging all of us to open our minds and hearts so that we can know beyond the boundaries of what is acceptable, so that we can think and rethink, so that we can create new visions…education is about the practice of freedom.” It is not only about opening the mind, but also the heart, and I would add the whole body. It opens our eyes to seeing differently, to move differently in the world, to embody the knowledge we learn, to find the words to name “those ideas which are nameless and formless-about to be birthed, but already felt” , as Audre Lorde wrote in Poetry is Not a Luxury. I often have my classes read this influential essay exchanging the word Poetry for Art. Teaching for me is about giving them the tools to be able to express what’s already inside of them, to learn new lenses to be critical of their positionality and intersectionality.

Teaching is also about being open to learning, to be inspired by your students, to be willing to change the syllabus according to the community and container that the classroom becomes. I also make an effort to expose my students to queer and BIPOC artists and theorists, which are constantly overlooked in the academy. This radical space of possibility is finite, you might have a student for a semester or two, but the hope is that the tools they learn will serve them for their entire lives and hopefully become agents of change. I’ve been teaching long enough that some of my students have gone to grad school and are now teachers themselves. Teaching is about passing on knowledge, a container pouring into another, but paradoxically never emptying itself but constantly replenishing with more water.

VC: When it comes to photography, what role does it play in your work and how did you begin experimenting with the medium?

ER: Photography was my first medium, I began taking photographs when I was 13 years old and I truly believed I would become a photographer. I took photography classes in school and workshops outside in La Escuela Activa de Fotografia en Coyoacán, as a brown queer teenager the darkroom was a safe space to hide from my bullies. Every Saturday for years I helped the photographer Enrique Segarra López, a student of Manuel Alvarez Bravo, in the plaza of San Jacinto in San Angel. He was then in his eighties and would sell his iconic black and white photographs of Mexico, and share his stories with everyone.

We had a photo club where we would have critiques of our work at breakfast, it was an intergenerational gathering of people that loved the medium. When I dropped out of studying medicine at the UNAM , I left Mexico to study in Canada at Emily Carr University in Vancouver. When I tried to sign up for more advanced classes in photography since I had worked on the medium for a while they said all the intro classes were a requirement. As a protest, I refused to take the intro classes and I switched to the Film, Video and Integrated Media program, where I discovered performance art and never looked back. I also never took a single photo class in my undergrad.

Nonetheless, photography is still a really important part of my practice, thinking about performance documentation but also in my stop motion animations, and installations. I always consider the photographic frame in the videos I produce and in the stills that become representative of each performance. I also use photography in installations, and have been debossing text in photographs printed in Hahnemühle cotton rag paper, where the text is revealed as the viewer approaches the image. I often think of performance and photography as interconnected, is there an image that captures the essence of the work, that translates the poetry of metaphor and carries the meaning of the piece.

VC: Instructions for Becoming is one of my favorite photographic explorations in your body of work. How did it come to be and what makes you interested in representing the land/body relation in this manner? Can you expand on the relation between body fragmentation, nature, and queer aesthetics presented through this body of work?

ER: Instructions for Becoming is a work that started in 2019, when I was able to go back to Mexico after almost two years of not being able to return or leave the United States when I was processing my green card. When I was able to come back I wanted to feel rooted to the land I was born in, and I felt trees represented that connection to the land, and the symbiotic relation to the human body. One of my mentors, photographer Laura Aguilar had just recently past away from complications of diabetes. Her most known works were photographs where she placed her nude body in the land as a rock, a crack, a desert, a boulder. Works that include her series Grounded, or her Nature Self Portraits, shot in New Mexico, Texas, and the Mojave Desert in California (all places that used to be Mexico before the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed in 1948, and the Battle of San Jacinto in 1836). I was interested in thinking about homage both to my land and to the queer Mexican American photographer who had such an influence in my work. Aguilar herself began this series grieving the death of a close friend in 1992, and as a homage to Self Portrait with Stone by photographer Judy Dater made in 1981.

The first photographs of Instructions for Becoming were taken in Amatlan, Mexico by one of my high school bullies who had showed up to one of my performances at Museo Tamayo, he apologized and invited me to spend sometime in his cabin in Tepoztlan. I didn’t bring a tripod to the trip, so I gave him the camera showed him the exact frame I wanted and I proceeded to lay in the roots of a ceiba tree in the Poza of Quetzalcoalt for hours, until I lost sense of my body and truly felt like becoming the tree. I could feel the ants crawling on my body, as well as the birds standing on the branches. I never felt more connected to another organism, and it felt like a spiritual experience. I continued the series laying on a branch of a palo mulato (Bursera simaruba), a tree that sheds its bark to get rid of parasitic species.

I needed to shed so much at the time, the dehumanization I experienced during my green card application process, the rampant xenophobia in the United Stats against Mexican immigrants after the 2016 election, the trauma I had lived growing up which I was processing as I reconnected and forgave my bully. I lay down holding on to the branch until I felt like my skin was peeling, learning from the tree as I surrendered to its branches. Soon after that performance theorist Rebecca Schneider asked me if she could write about the work. Schneider wrote:

“Thus, performance here is homage that branches in multiple directions –homage to the tree and the land and the artist’s migrant “roots,” and homage to artist Laura Aguilar with whose nature works Rojas’s Instructions explicitly resonate. Instructions for Becoming take up Aguilar’s gesture as if to respond in kind, like a wave of the hand is met with a wave in return, or instructions are met with reiteration. In this way, Aguilar’s call is re-called through Rojas (though she herself may be read not as origin but as responding to stone, just as Rojas responds to tree). In other words, Rojas’s performances take and pass instruction along in a vast relay of branchwork, limb to limb, call to response to call. As photographs, limbs-become-image move as pixels of light.” (Schneider, The Methuen Drama Companion to Performance Art)

VC: That is an incredibly emotional story, to see the evolution of people towards a more accepting heart. How has your approach to addressing discrimination, xenophobia, and colonialism evolved when reflecting on your traveling retrospective Tracing a Wound Through My Body at Lafayette College in 2021?

ER: Having this opportunity to look back at my work for the past 10 years, gave me an opportunity to step back and look at the different approaches I have taken as an artist in my practice and research. It allowed me to see how the work had evolved through time. The survey show was planned to open in the fall of 2020, but because of the pandemic it was postponed to 2021. Through the pandemic I also had a lot of time to reflect on how the work was addressing these systems of oppression and discrimination, and also how other artists were responding to the social and racial inequities that the pandemic laid bare. The exhibition changed because it had a whole other year to simmer. I had the privilege to work closely with curator Laurel V. McLaughlin, who had just traveled to the retrospective of artist Rina Banerjee, Make Me a Summary of the World, and she suggested that we travel to the exhibition, with a new commission in each institution and an accompanying bilingual catalog. This allowed me to both look at the past and also where the work was going into the future, which meant the exhibition kept growing as it traveled and the pieces were exhibited in many different sites. I feel that this exhibition changed the way I approach these issues because it gave me time to pause, reflect and process over a decade of making art with communities, and gave me a chance to think deeply of what comes next.

Editor’s Note: A following interview will be published in the month of February

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Lee Gap-Chul: Conflict and ReactionJanuary 14th, 2026

-

The Favorite Photograph You Took in 2025 Exhibition, Part 2January 1st, 2026

-

The Favorite Photography YOU Took in 2025 Exhibition, Part 3January 1st, 2026