Ellen Mahaffy: A Life Undone

This week, we will be exploring projects inspired by intimacy and memory. Today, we’ll be looking at Ellen Mahaffy’s series A Life Undone.

I first came across Ellen Mahaffy’s work last Summer. Some of her images were submitted to an open call through Midwest Nice Art, a collective I run with my husband, Tim Rickett. Dana Smessaert juried the exhibition, tl;dr, and I couldn’t stop looking at Ellen’s images. Many series work together with other images, but some artists struggle to make images that can stand alone; Ellen is not one of those artists. While her series A Life Undone focuses on her relationship with her father, each image can stand as a portrait on its own. My personal favorite, No One Home (People Need People), is a complex exploration of personal artifacts, found objects representing home and hobby, and notes, all through traditional studio photography techniques. Spend some time with Ellen’s images individually as they each have an abundance of stories to tell.

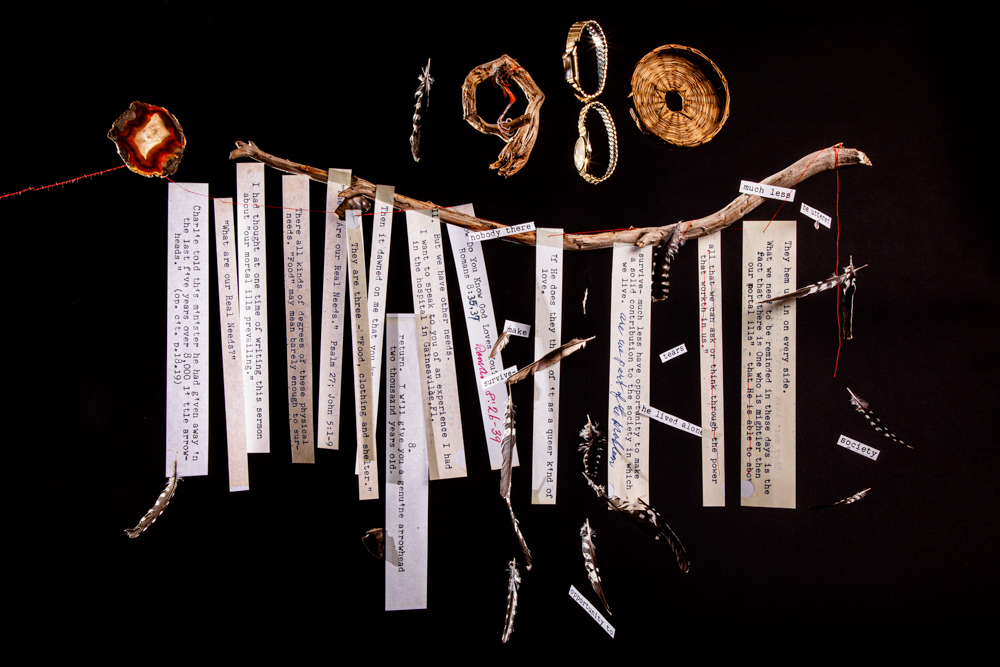

©Ellen Mahaffy, No One Home (People Need People), 2023. Ash Stump with handmade saws, woodpecker feathers, red thread, and ant. Grandfather’s 1980 diary also notes Grandma’s broken hip.

Ellen Mahaffy grew up in a rural town just twenty miles south of Rochester, New York. She earned her BFA in photography from Maryland Institute College of Art (1987). In 1993 she earned her MFA from the Visual Studies Workshop, which was affiliated with State University of New York, Brockport. Her Visual Studies degree focused on artists’ books, multimedia, and photography. Currently, she is a professor at the University of WisconsinEau Claire teaching visual communication and photography for the Department of Communication and Journalism.

Mahaffy’s artistic interests are surreal landscapes, abstracts, still life, and artists’ books. Her current work circles back to an earlier project, Nothing Was Ever Said (1993), which explored the familial relationship between her Presbyterian Minister grandfather and his adopted son, her father. Her father’s passing in 2019 inspired her to resume an investigation of her familial roots and rethink ideological differences from sexuality to gender to religion and belonging.

Mahaffy’s work has been shown in several solo shows, group exhibitions, and various juried shows. Among the notable jurors are Jess Dugan, Joyce Tenneson, Carol Erb, Fran Forman, Dana Smessaert, Mary Statzer, and Julian Cox. Her latest work, Worn by My Father, received Best of Show at Confluence of Art: Annual Exhibition (2022). Recently, she was awarded an internal university grant to support her ongoing project, A Life Undone.

Follow Ellen on Instagram at: @emahaf

A Life Undone

What is loss? What is memory? How does one live their life? I left my father. Now I am left with what he left behind.

Epiphany Knedler: How did your project come about?

Ellen Mahaffy: A Life Undone reflects my uneasy relationship with my father. I distanced myself from him multiple times for a variety of reasons. The longest period was out of fear for about 20 years. As a queer person, how could I come out to him when he believed Democrats are evil? As a longtime NRA member would he turn his guns toward me and my partner? Only when death was imminent, did I reveal my sexuality to him.

He lived a simple life, primarily alone with over 30 cats and other critters as companions.

He preferred to live off the grid, sustaining himself on his mother’s stocks and his social security. When the well ran dry on his property, he declined help from others and refused to connect to municipal water.

After his passing, I had questions to unravel. Was he dangerous? How did his life become undone? Did he have a productive or meaningful life? He talked about clockwork, gunsmithing, and woodworking projects he wanted to complete, but neuropathy in his hands prevented him from doing these projects. What is family? What does it mean if a parent opts out of responsibilities for others, especially their children? He had very little interaction with us. Could he have been schizophrenic or suffered from another mental illness?

My mother left him when I was twelve. He held stereotypical heterosexual masculine ideals where the “wife” was supposed to support his work and other needs. This dynamic became a toxic environment. I feared being harmed if I were to ask permission to take violin lessons. He lashed out when I nudged the thermostat to kick the heat on after the fire went out in the fireplace.

Despite my visits to see him as a teen we never really got to know each other. His mother tried to pressure me to make meals for him. Between my grandmother’s unrealistic expectations for a 12-year-old, and my father’s lack of warmth and receptivity towards me, I stopped trying. Keep in mind that as a Presbyterian minister’s wife, her calling was to support her husband’s work. She was a stern woman. My father was not any kinder.

As I sought out sources to understand a cultural shift away from the biological family unit to one where folks find their own support systems, I learned about a rise in folks who die alone. In an episode of Larry Bernstein’s podcast What Happens Next, Bernstein interviews Stefan Timmermans, co-author of The Unclaimed: Abandonment and Hope in the City of Angels. When discussing the growing phenomenon of persons unclaimed at death, the author states that “the unclaimed reflect a deep sense of social isolation caused by eroding family ties” (Bernstein 2:38). Timmermans also shares that there are estimates of 150,000 unclaimed persons every year in the United States (Bernstein 1:47). This investigation into unclaimed persons sparks new questions: When you die, who will give you the rites of passage? Who will remember you? What traces have you left?

Burying our dead is economically challenging. My sister and I went against my father’s wishes for a casket burial. Instead, we scattered his cremains around his house as In Memory of David Mahaffy depicts. David Mahaffy found joy in fast American sports cars (and their tiny replicas), wood, and markspersonship; yet the only marks left are the scratches left in the wood, paper, and soil.

What relationship does memory or intimacy play within your practice, and does photography become a way to navigate these complex topics?

Intimacy was never exhibited in my family. When my paternal grandfather, a Presbyterian minister, passed in the late ‘80s, I delved into a project that I hoped would help me better relate to him, and thus my father. I poured through my grandfather’s study (diaries, sermons, letters) seeking clues into my father’s origins. This early work resulted in a sitespecific installation, Nothing Was Ever Said, at my father’s place.

My father, who was adopted as a toddler, was told he was 100% Czechoslovakian. He deeply feared he had a Jewish heritage. Was he antisemitic? My digging through my grandfather’s documents failed to unearth any more details surrounding my father’s adoption. I am left with my own speculations.

For A Life Undone, I found myself in a similar mode to the previous piece, documenting what was left behind, photographing clothing, various artifacts, and his property. As I reviewed my grandfather’s Kodachrome slides and diaries, I discovered various objects at my father’s place. A couple of items included a lawn chair and a Davenport sofa. This sofa symbolizes a pattern where items were not discarded, and instead handed down to the next generation and reused. This process reconnected me to a time when we were a family celebrating holidays and birthdays together. These images also jogged my memory of the first fish I caught and my desire to help my father build our house. I incorporated the wallpaper I selected for my bedroom in this house as a backdrop for the studio still life that refer to my life at that time (The Apple Does Not Fall Far from the Tree).

Is there a specific image that is your favorite or particularly meaningful to this series?

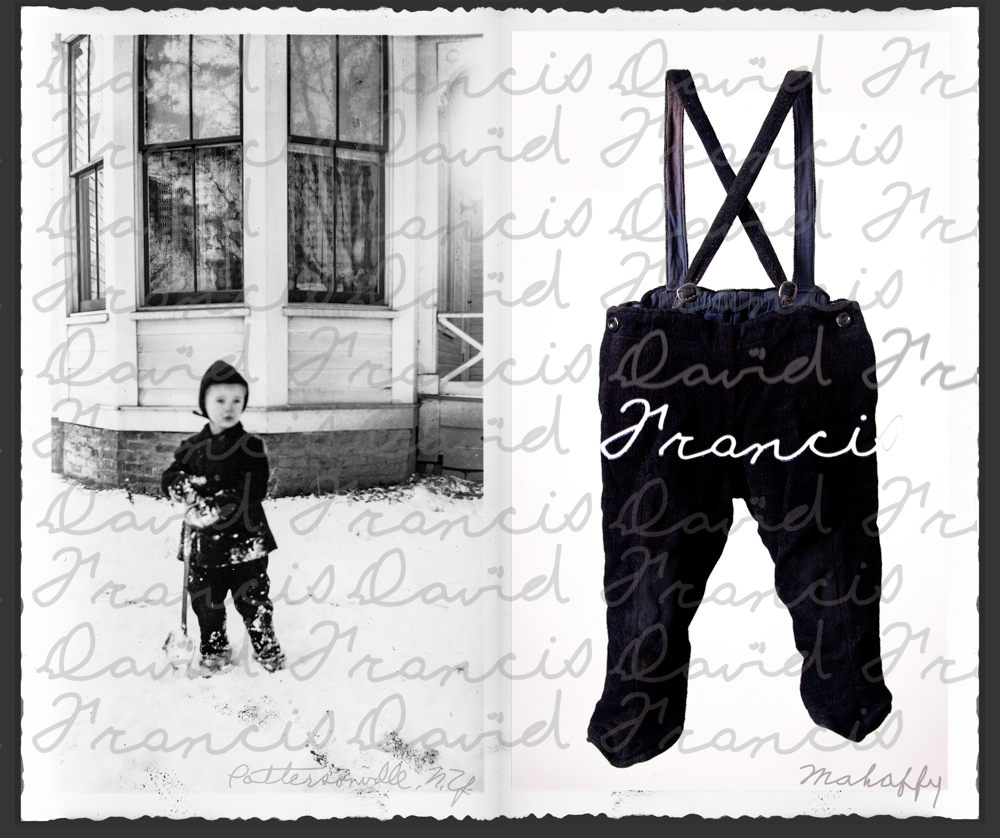

There are several. Snow Pants Diptych pairs a family photo of my father at age 3 with a studio shot of the same snow pants that he wore as a child. The back of the family photo is inscribed in my grandmother’s handwriting, “David Francis Mahaffy,” which I overlay onto the image.

©Ellen Mahaffy, In Memory of David Francis Mahaffy, 2022. Panorama collage pieces together four different moments: My sister Christine and me at the back door after spending the day sorting the contents of the house (2022); a good friend Geoff scatters David’s cremains (2021), a family snap of us wearing a historical dress for the 1976 celebration and David’s snapshots of critters hanging out at the backdoor (circa 2003).

In my early twenties, I learned of my father’s adoption from my mother. Although she said it was not a secret, I do not recall any conversations that revealed his origins. Because of New York State laws, his adoption was sealed. Shortly after his death, New York State revised its original birth certificate laws, allowing me to obtain his certificate. I discovered that Francis Wayne was the name his birth mother gave him, which his adoptive parents changed to David Francis. To bring attention to this distinction, I created an emphasis in the overlay.

In Memory of David Francis Mahaffy, I stitched multiple images that link an old family portrait with my sister on the back steps with a current portrait. For the background, I pieced together his house. On the right, stands a masculine figure scattering cremains throughout the ivy surrounding the foundation of the house. I also added a series of images he took of the critters. I am fascinated with how a place can hold multiple moments in time and how I can articulate that with photography.

©Ellen Mahaffy, Worn by My Father: triptych, 2021. My father never threw things away. Probably because living in a rural area, he had no garbage service. Or because he grew up with influences of reuse or repurpose. His father’s red overcoat with gloves still in the pockets, T-shirt worn while he toiled with raw lumber for future gun stocks, and a hunting vest in which he would manually fill the shells.

In Worn by My Father Triptych, I combined images of a t-shirt he wore to cut lumber, a hunting vest with loaded shotgun shells, and an overcoat that was once my grandfather’s. He kept his father’s clothes. Was he being thrifty, or did he want to maintain a connection to his father? As a kid, I loved hiding in my grandfather’s closet amidst his shoes and suit jackets. In the various pockets, I discovered gnarled-up gloves, remnants of a Presbyterian minister making calls, and his mineral-collecting avocation. I realized that my father preserved his memory of his father by keeping things as my grandfather left them. I expanded upon this idea with a subset of images; suit jackets, hats, and slacks. Although he once proclaimed that he too could be a minister, and he did sleep with a bible by his bed, his reading collection belies any predilection towards piety. His house contained stacks of porn magazines, books on gunsmithing, and sports car manuals.

©Ellen Mahaffy, Lawn Chair, 2021 & 1973, The image pairs a senior citizen outing with the lawn chair in its current location outside my father’s backdoor.

Can you tell us about your artistic practice?

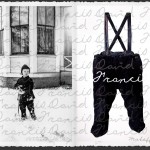

J. Halberstam asks in The Queer Art of Failure, how can we fail well? Thus, how do we “push through the divisions between life and art, practice and theory, thinking and doing, and into a more chaotic realm of knowing and unknowing?” As a practicing artist, I study relationships and how things connect and relate to one another to create a cohesive visual design. For instance, a studio still life starts simply, maybe a few elements at a time, as I have a slight idea of the direction I want to take. No One Home (People Need People) referenced when my father was in the hospital and his solitary life. My father was about to be released from the hospital from an illness that almost killed him when he fell, breaking his hip.

My grandmother also broke her hip. This accident occurred during a trip to their winter home in Florida. I read an entry in my grandfather’s diary from that fateful 1980 trip in which he met a lonely gentleman on the same hospital floor. He wrote in red pen that this man had no one at home to care for him. He later wrote about this in a sermon, “people need people.” I copied the sermon, cut up the lines, and placed them into the setup. I selected a piece of an ash tree that was cut down due to the emerald ash borer as a focal point. I also found woodpecker feathers and legs and poked them through the stump hollow. Woodpeckers are woodworkers, thus connecting to my father. For the still life to feel finished, I added wood shavings as if the cutting had just occurred. Hence, the construction is a gradual process.

The results often surprise me. On occasion, they disappoint me as a piece may need further development. If it does not work the first time, the next time I build upon that experience. Thus, it is important for me to draw from my father’s archive; I am not always sure of the connections, but I have the source material from which to appropriate and tell stories of my father’s complicated life.

©Ellen Mahaffy, Worn by My Father: 1950’s Harris Tweed Jacket Triptych, 2021. This series revolves around my grandfather’s advocation, mineral collecting. My father, David, memorialized his father, Robert, by keeping his clothes, leaving signs of his vocation as a Presbyterian minister and his avocation as a mineral collector intact. He too would collect items he found from plowed family farm fields.

What’s next for you?

I continue to sort through the ephemera left behind and photograph more studio still lifes. Since the material is abundant, I would like to create a book. This format would allow me to expand the reach/impact of the project. Not only would a book provide more room for a larger edit of the images, it would also allow me to unpack more elements about toxic masculinity, sexual identity, and other latent elements of our family dynamic.

I also foresee integrating video and sculptural pieces to create an immersive experience of my father’s existence.

My fourth solo show is this fall. This show will be the first time that segments of A Life Undone will come together. The regional exhibition will be shown in the gallery at the L. E. Phillips Memorial Public Library in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, October 26th – December 31st.

©Ellen Mahaffy, Nesting, 2022. My father proclaimed the title gunsmith during a graphic design class at a two-year college. He worked in the trades as a woodworker, carpenter, and blacksmith and would make his own rifle stocks. As a long-term NRA member, he had a love for guns. As a queer person, I was never comfortable “coming out” to him and became estranged in fear of potential rage.

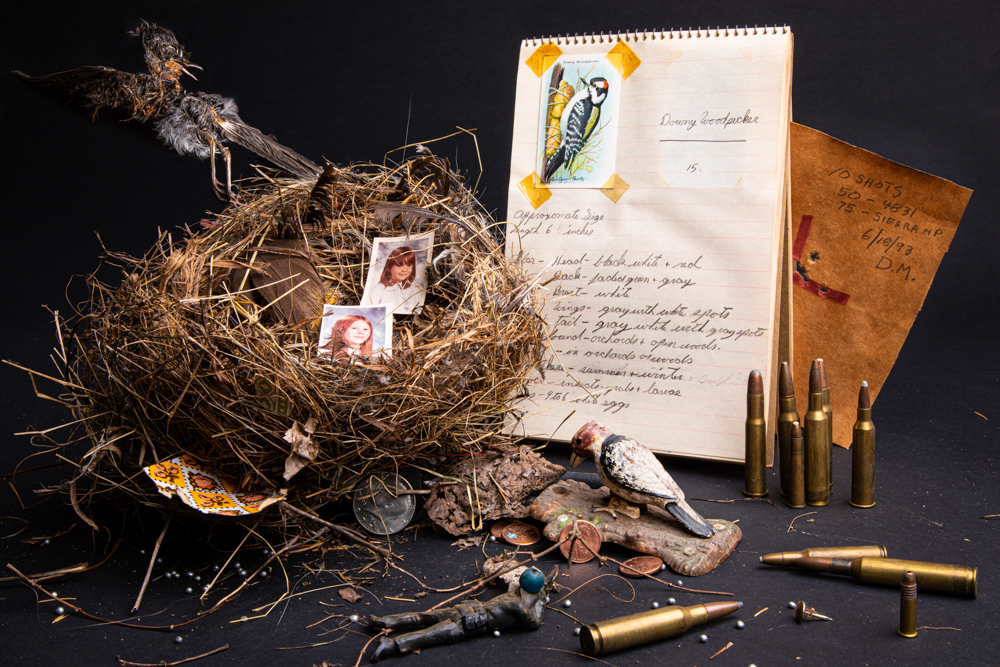

©Ellen Mahaffy, I Cannot Be Reached, Telephone with Our Numbers Triptych, 2023. Wall mount rotary telephone without cover with switch, red wiring, house key, and busted carpenter’s tape. Handwritten slips were tacked near the phone. David never called. The assembled still life draws from what remained in my father’s house. He did not care for the telephone and discounted his service late in life.

©Ellen Mahaffy, 1980 Sermon, 2023. Clips from my grandfather’s sermon. 1980 was the year my grandmother fell and broke her hip. They drove down to Florida for the winter but never made their destination. Relatable personal experiences that seem to hold true today.

©Ellen Mahaffy, Red Camaro & Shop, 2021 & 1966. The image pairs an old family snapshot of great-grandmother’s roadside farm stand, moved to the current location in 1966 now referred to as the shop. The addition was added in the 70s for automotive repair and blacksmith forge.

Epiphany Knedler is an interdisciplinary artist + educator exploring the ways we engage with history. She graduated from the University of South Dakota with a BFA in Studio Art and a BA in Political Science and completed her MFA in Studio Art at East Carolina University. She is based in Aberdeen, South Dakota, serving as a Lecturer of Art and the co-curator for the art collective Midwest Nice Art. Her work has been exhibited in the New York Times, Vermont Center for Photography, Lenscratch, Dek Unu Arts, and awarded through the Lucie Foundation, F-Stop Magazine, and Photolucida Critical Mass.

Follow Epiphany Knedler on Instagram: @epiphanysk

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photography Educator: Juan OrrantiaDecember 19th, 2025

-

Bill Armstrong: All A Blur: Photographs from the Infinity SeriesNovember 17th, 2025

-

Rebecca Sexton Larson: The PorchApril 28th, 2025

-

Matthew Cronin: DwellingApril 9th, 2025

-

Melissa Grace Kreider: i will bite the hand that feedsSeptember 25th, 2024