Student Prize 2024: Top 25 to Watch

Every year, the Lenscratch Student Prize Awards give us an opportunity to celebrate and support the next generation of photographic artists. Hundreds of artists shared their work with us– powerful creative voices that make us truly excited about the future. Before we begin the celebration of our 7 winners tomorrow, we wanted to shine a light on 25 photographers that you should have (and keep) on your radar. Congratulations to all!

An enormous thank you to our jurors: Aline Smithson, Founder and Editor-in-Chief of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Daniel George, Submissions Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Linda Alterwitz, Art + Science Editor of Lenscratch and Artist, Kellye Eisworth, Managing Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Alexa Dilworth, publishing director, senior editor, and awards director at the Center for Documentary Studies (CDS) at Duke University, Kris Graves, Director of Kris Graves Projects, photographer and publisher based in New York and London, Elizabeth Cheng Krist, Former Senior Photo Editor with National Geographic magazine and founding member of the Visual Thinking Collective, Hamidah Glasgow, Director of the Center for Fine Art Photography, Fort Collins, CO, Yorgos Efthymiadis, Artist and Founder of the Curated Fridge, Samantha Johnston, Executive Director of the Colorado Photographic Arts Center, Drew Leventhal, Artist and Publisher, winner of the 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize, Allie Tsubota, Artist and Educator, winner of the 2021 Lenscratch Student Prize, Raymond Thompson, Jr., Artist and Educator, winner of the 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize, Guanyu Xu, Artist and Educator, winner of the 2019 Lenscratch Student Prize, Shawn Bush, Artist, Educator, and Publisher, winner of the 2017 Lenscratch Student Prize.

© Natalie Arrué, from the series Contra Tu Pecho

Natalie Arrué

Georgia State University, BFA in Photography

Growing up as the youngest in a family of six, I’ve mainly known my family’s life through old photographs. Seeing these images, I felt a sadness for not sharing their same memories and losses. My parents, immigrants from El Salvador, struggled to balance their heritage with raising American children but made sure to document their lives simultaneously. While investigating these photographs repeatedly, I found my family’s connection to our culture has changed. We are now grasping onto our heritage as if it could disappear.

This new archive represents our unconscious subverting of culture though a staged family archive. Symbolic garments, furniture and flowers bind our existing photographs with these counterfeits, as they try to exist on their own. Resurrecting these family events, reexamines our experience in the United States but also the effects of the loss of culture and identity as time advances.

Follow Natalie on Instagram: @photogrphic

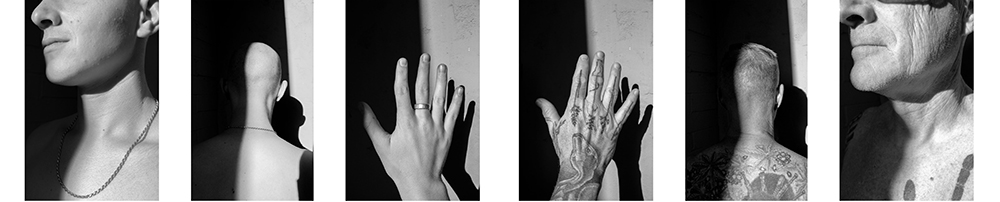

© Elizabeth Blackie, from the series Outlines

Elizabeth Blackie

Falmouth University, Bachelors

Led by intentions of questioning, Outlines (2024) is an ongoing introspective enquiry into the self. Uneasy with my identity and sense of place in my environment, the series is both a work of fiction and documentation of an investigation into how we can formulate an understanding of the detached self. Alluding to the subconscious, the work brings attention to the restless moments of isolation and lack of connection that can be experienced with both people and environment. Beginning as a means to understand the inexplainable feelings I was experiencing at the time, I used visual imagery to articulate these struggles. Aiming to produce a series that follows a journey of reflection, this body of work comments on the existential state of the world we currently live in, the unknown futures caused by the continuous changes and state of fear surrounding us. Depicting fragments of dreams and nightmares, contemplating the known and unknown, rearranging visual perceptions of what is real. Outlines introduces a visual inquiry into how things can appear familiar but uncanny when one starts to question identity and place.

Follow Elizabeth on Instagram: @elizabethblackie_

© Natalie Brescia, from the series Overlook

Natalie Brescia

Massachusetts College of Art and Design, MFA in Photography

My artistic research explores the concept of land as a container for personal and collective history, gesture, interaction, vulnerability, and associated memory. The way in which one relates to the land is heavily influenced by how each environment is depicted and represented. Photography and lens based media have been instrumental in shaping the idealized and romanticized perception of the American landscape. The Four Great Surveys of the West as well as the Pacific Railroad Surveys acted as means to classify, catalog, and map the land. These images imposed a rational order on nature, propagating a belief that if a photograph could capture the vastness of the American Landscape, so could humans. A production of desire, a desire intertwined with the legacies of colonialism and capitalism, was created to promote settlement, reaping of resources, and tourism.

My research practice begins with examining the archives of the photographic surveys, mapping the history of conquest, and then inserting myself into the Western landscape. The land itself is seemingly preserved yet twisted by the images that were utilized to promote Manifest Destiny, Ford Motor Company advertisements, and current day social media postings. I employ the photographic medium to emulate historical and societal practices but in a gesture of defiance. Unlike the meticulous precision of the surveyors and naturalists, my images do not seek to reproduce the land. Instead, I aim to disrupt the conventional relationship between the body and the land, questioning the very act of photographing the landscape.

This disruption of the bodies’ relationship to the landscape begins in the act of creating an exposure. While these photographs may appear as if they were created through collage or digital manipulation, they were made with multiple exposures in camera. Equipped with a waist level viewfinder, the medium format film camera used for this project choreographs my movements. I create an exposure with the landscape ahead of my body, reinsert the darkslide, cock the shutter, turn my back on the same subject and bring my camera overhead. My muscles engage and stretch as my back arches to adjust to the new perspective. The landscape becomes anew, inverted, reflexive. The act of arching the back is an unnatural gesture, exposing the heart and throat, two of the body’s most delicate and sensitive areas. This movement signifies a subversion of historical photographic norms, highlights my vulnerability within the space and acknowledges the vulnerability of the environment.

The culmination of this project takes shape in the form of an accordion book, connecting the horizon lines from each double exposure. Drawing inspiration from the photocollage style of Ed Ruscha, the folded pages create a continuous, flowing image that echoes the fluidity of the landscapes and narratives explored throughout the project. This tangible form serves as a testament to the complexity and interconnectedness of the historical, cultural, and physical layers embedded in the American West’s landscape.

Follow Natalie on Instagram: @nataliebrescia

© Jacob Church, from the series Loon

Jacob Church

Massachusetts College of Art and Design, MFA in Photography

Loon is an ode to all the little towns where surfaces are rougher, things are older, and people work to survive. I feel at home in towns like this. Although these images are products of an intuitive practice based upon immediate response, an internal proclivity for yards, fences, chipped paint, stray cats, dogs, and midwesterness unconsciously shape the project. Towns I visit on the east coast have a similar ethos to the spaces that raised me back in Ohio. I see this condition on the surfaces of buildings, painted on cars, and in the faces of strangers on the street. I feel a connection to all of it. This work is about an anti-social kind of harmony. One where mundane places, people, and things radiate a similar melancholic bliss. If there is a through line or a certain kind of beauty, it’s one of love tethered to discontent, tenderness in rough places, and unconscious longing. I hope to create with this aggregate of images a sort of constellation of self. One that walks through many different moments and spaces but remains grounded in a sensitivity to the outside world that may speak to an inner one.

Follow Jacob on Instagram: @jacob_church1

© Wyatt Collins, from the series Metamorphosis

Wyatt Collins

University of North Florida, Bachelors in Photography

Throughout my life, I’ve had a keen eye for my surroundings, from the people I’m surrounded by to the activities I engage in, and even my own beliefs and habits. These familiar elements have always provided me with a sense of stability and comfort, as they offer a reassuring sense of familiarity in an ever-changing world. This observation is crucial in understanding the motivation behind my recent body of work, titled Metamorphosis.

Observing and being aware of one’s surroundings is the foundation for self-awareness and introspection. By paying attention to the details of our lives, we gain insights into how our environment shapes our experiences and influences our sense of self. However, as of late, I’ve come to realize that these familiar aspects of my life, which once provided comfort, have begun to have negative effects. Instead of feeling grounded, I’ve started to feel unsettled and uncomfortable with my current state. This realization highlights the concept of personal growth and the discomfort that often accompanies it. Sometimes, what once served as a source of stability can become a hindrance to our development. Recognizing this discomfort is the first step toward initiating change. This discomfort and realization of the need for change inspired me to create Metamorphosis, a body of work that explores the tension between the desire for change and the fear of uncertainty that change brings. Change is a fundamental aspect of life, but it can also be daunting and intimidating. The push and pull between the desire for transformation and the fear of the unknown is a universal human experience. By exploring this theme, I aim to shed light on the complexities of personal growth and self-discovery. Metamorphosis involves navigating the unknown, shedding old habits, beliefs, and behaviors, and even losing connections with loved ones. Change often requires letting go of familiar patterns and relationships that no longer serve us. This process can be painful and isolating, as we confront the loss of what was once familiar and comforting. The discomfort and isolation that accompany change are central themes in this work, as I explore how they shape our sense of self and our place in the world. Change challenges our identity and forces us to reevaluate our place in the world. The discomfort and isolation that come with this process are integral to understanding the transformative nature of personal growth. To visually convey the passage of time and the complexity of change, I use multiple frames in my photographs. Using multiple frames allows me to capture the gradual evolution and transformation that occur over time. It provides a visual narrative of change, showcasing the different stages and experiences that shape our lives. Ultimately, my goal with this collection of photos is to encourage viewers to reflect on their own experiences with change and to embrace the transformative potential that comes with navigating the uncertainties of life. I hope to inspire others to embrace change as a natural part of life and to see it as an opportunity for growth and self-discovery. By sharing my journey of transformation, I aim to empower others to embark on their own paths of personal evolution.

Follow Wyatt on Instagram: @oh__________boy

© Nathan Cordova, from the series Feeling a Future Coming

Nathan Cordova

University of Arizona, MFA in Photography, Video and Imaging

Feeling a Future Coming considers the potential of friendship and offers a pointed critique of institutions and our consumption of their products. Friendship is slippery and difficult to maintain. There are social and cultural taboos that attempt to constrain our friendships. This is a social experiment that breaks through the isolation we all feel. What does it say about our present moment where amidst profound loneliness, we desire visceral connections with each other in order to transcend the limits of our individual bodies? By inviting participation, I’m asking myself and my friends to step out of this isolation and to encounter each other anew. I’m valuing critical connections over critical mass, applying force on strategic pressure points that form the boundaries of typical friendships. There is a momentary embodiment of liberation in this act, as I re-imagine what is possible.

I appropriate and recontextualize collections of digital images of western domination gathered from the internet. This involves engaging with both the visible architecture like the skyscraper, and the supposedly invisible infrastructure, such as data centers and military drones. Anger and pleasure play an important role, offering a means of embodiment and exploration of the collection’s emotional and sensorial dimensions. Through a material intervention, I challenge notions of fixed identity and embrace the fluidity and multiplicity of human experience. This interruption utilizes an interdisciplinary process of layered blurring that transforms their symbolisms into something elemental; liquid and flame, semen and squirting, embodied presence etching sunlight and sifting blood. Blurring the boundaries between past and present, self, and other, I invite viewers to engage these collections on a visceral level through the presence of their own reflections in black acrylic surfaces mediated by images layered with physical ejaculate, traces of our sequential self-pleasure. Remixed marketing videos from The University of Arizona and Raytheon (now rebranded as RTX Corporation) point to their mutually beneficial relationship built on endless cycles of debt and death. All of this works together to disrupt conventional modes of perception. Challenging the rigidity of these images as repositories of meaning and enforcers of social order, Feeling a Future Coming reconfigures their signifiers to a point of emergence, where all futures become possible again. Reclaiming agency over our bodies and desires is a fundamental step toward liberation, contributing to a more empathetic and introspective society that questions rigid authority and embraces the beauty of uncertainty.

Follow Nathan on Instagram: @Nathan_Cordova_Artist

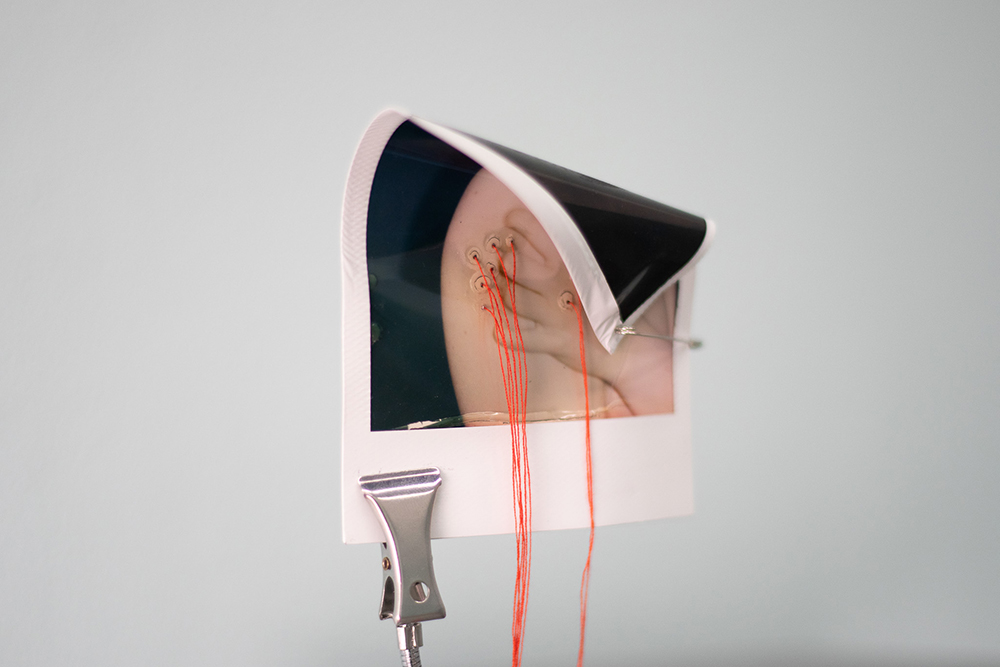

© Emily Damyan, from the series The Weight of Silence

Emily Damyan

University of East London, BA (Honors) in Photography

The Weight of Silence explores the stigmatisation of abortion and how it can impact personal narratives. Combining photography with sculpture to address introspective physical and emotional difficulties experienced within my own abortion, this body of work has not only been catharsis in processing trauma but also an act of reclamation—reclaiming narrative, space, and autonomy. By sharing my experience it aims to challenge stigma and contribute to a broader conversation about healthcare access and the often-unspoken diverse realities of abortion.

Follow Emily on Instagram: @emily__damyan

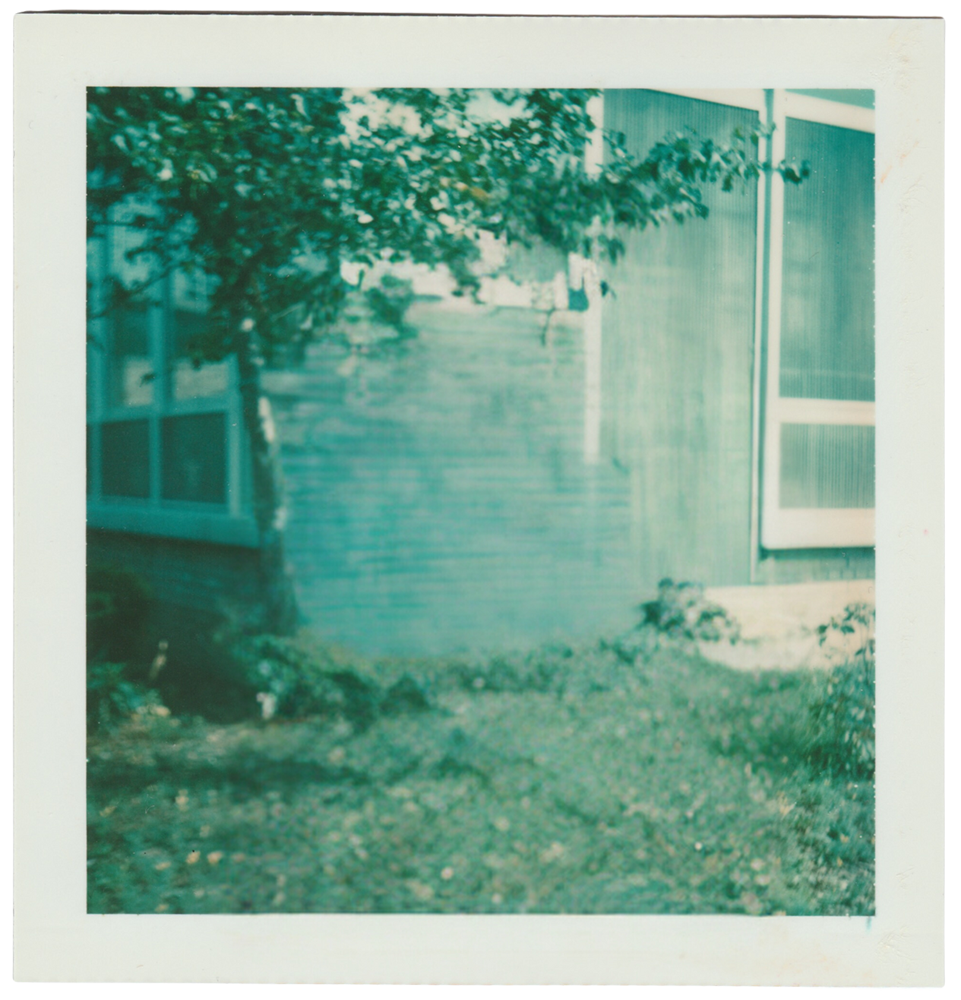

© Ariana Gomez, from the series My Mother Speaks of Land as Memory

Ariana Gomez

University of Texas at Austin, MFA in Studio Art

My mother speaks of plants. To her, we are created with roots that snake down into the deep, dark earth inserting themselves like veins into our hearts, into our souls. For her, this is truly home; a soul home. And hers has never been Texas. You see, she was uprooted. Her soul home is Puerto Rico, the place she only remembers as a small child when everything is towering, and colors are the most vivid. Her roots tore as she boarded a plane at eight years old, never to return. She speaks of unlived lives in the lush watery world where she last thrived.

My father spoke of God. To him, Texas was God’s Country and there could be no other place in the world more important. Texas was his soul home. He died here, having fully rooted himself into the semi-arid soil.

I speak of juxtapositions, and insertion. My mother and father now occupy parallel existences of time while I insert myself into their memories, dredging the hot earth for a glimpse of their life together. I used to spend my time only looking for my father. He was the one I couldn’t grasp onto. He was the one I couldn’t find. However, while searching for my father in the desert landscape, I found my mother attempting to ground herself within this foreign earth. She tries to root herself into the densely packed soil of my father’s landscape, her children’s landscape, her perceived home, yet fails. Through this discovery, I have subconsciously linked the three of us together through place, through time, through memory, a trinity of searching. I have become an amalgamation of my parents and situate myself within their two landscapes as a bridge. We are three – past, present and future, a trinity of faith in the earth, in home, in identity.

I think often of how we perceive, explore and own our identities. How is a perception of ‘self’ created, and what ideology do we tie ourselves to? Who owns this? Who is allowed to knot their identity up so tightly within generations of history to become stronger? And who is made to cut their ties and live with short strands of flimsy cord tied haphazardly to vestiges of place and time? I come back to land. Land creates histories through ownership, through nostalgia, through archival memory. Landscapes create a perception of home, a memory-scape we long for in moments of change and upheaval. And the idea of home is a strong one, embedded in the psyche as something idealistic – a place to long for, or strive towards, or rally behind within cultural, spiritual, and political identities. Often, this becomes an entire identity, taken over by the need to create a space entirely of one’s own. So then, what happens to the self when the idealization of home is connected to a sense of identity and the myth inevitably comes into question?

Using photography, writing and sound, I work to understand the link between identity, land, home and memory. My interest lies in the intersections of these mediums and how the three can work together as spiritual trinity to create an experiential memory-scape. My current project My Mother Speaks of Land as Memory was born through loss – lost land, lost identity, and the loss of past and future selves for my father, my mother, and myself. Deeply embedded within this grief for unlived lives, I create an installation-based memory-scape of place that becomes more fluid with each viewing. The images change, flow, and adapt to the world around me and within me, while sound and text keeps me grounded in the earth.

This installation simultaneously serves as an ever-changing, living archive of my own family and their history. Prior to this, I had never taken a single photograph of my father. After he died, the weight of this realization hung heavy on my conscience. It led me back to a questioning of ownership and of legacy and identity. Who gets to have an archive? And how does one create an archive after so many missed years? Inevitably, how does one make a person-less portrait? I always came back to landscape. I personified my father through the Texas landscape. And while searching for him in this arid earth, I found my mother an immigrant by way of Puerto Rico who, after my father’s death felt unmoored in this vast sea of desert. Through my father and I, she became embedded in this foreign landscape, losing ties to her own history and grasping at the loose ends of her identity.

In losing my father, I became closer to the idea of exploring my mother, as my generational history was starting to fade. This has pressed me to scour what remains of our family’s material archive, which includes a few 8mm videos my mother took in college when attempting to become a documentarian. I took these and created an experimental 25-minute film that explores her own feelings of being torn from her rooted earth. Together with my installation, I am presenting the severed ties of the past in nostalgic Kodachrome. But I am asking – does this past exist as we remembered it, and how far does it reach into the blue of distance that memory and time create? I present these materials on a dark blue wall – an homage to Rebecca Solnit and a remembered distance.

Through all of this, I am reminded of the history of Aztlan – the mythical homeland of the Aztecs, and the place revolutionary Chicanx culture rallied behind. All for a place to call home, all for a history that was taken from them, first by the Spanish and then by a steady succession of any/all colonizers. I’m intrigued by the memory of a created diaspora, shared by many across time and generations. Land, as we return to, creates histories. And histories create a sense of place and belonging. As a child descended from the mother who was torn from her land, and a father who lost any connection to this Aztec place of spirituality and wholeness, I am desperate to find a home that we can share, between worlds, between landscapes, between time. For it was only upon returning to Texas, the place of my birth, that I realized home is an idealization and amalgamation of every single memory and experience we choose to cling to. Home exists as a myth would; as powerful, repeated, collective affirmation. Through the combining of images, text and sound, my work perceives home as existing in the space between reality and abstraction.

My practice seeks to engage in dialogue about who owns history, who owns their identities, and who must create shared diasporic experiences simply to survive in the world. My mother, my father and I span three separate existences across time that coalesce in the shared memory of reconciliation and understanding. Grief is universal, but my experience through generational migration, and distorted memory is crucial to connecting with other communities. My artistic practice is flourishing not only for myself, but for my community and all those who understand and mourn the generational ties to a land, now long forgotten. I intend to pull from long histories to fight for my own experience of place, my mother’s threatened landscape, and my father’s forgotten sense of identity, tied to a homeland now known only as myth.

Follow Ariana on Instagram: @_arianagomez

© Francisco Gonzalez Camacho, from the series Reverting

Francisco Gonzalez Camacho

Aalto University, MA in Photography

Ongoing work started in January in Reykjavik, Iceland, during the SIM international artist residency program. My stay involved a process of visual research through the materiality of photography on the commoditization of nature in the context of the booming tourism industry.

Gentrification, waste and environmental degradation are some of the problems related to tourism, challenging the idealized image of the Icelandic landscape. In order to create a more environmentally involved process, I created my own handmade recycled paper from waste. Reverting is a divergence from traditional printing approaches, exploring the materiality of the medium, the alternation between handmade and digital processes and the potentialities of the photographic image as an object.

I aim to mirror the transformative process of manifesting something from the void —a form of alchemy of waste— with the delicate equilibrium of our environment, and the perpetual cycle it follows.

Follow Francisco on Instagram: @frangccom

© Sophia Hadeshian, from the series There Once Was and Was Not

Sophia Hadeshian

CUNY Graduate Center, MA in Middle Eastern Studies

Drawing from my family’s history as descendants of Armenian Genocide survivors, There Once Was and Was Not considers how displacement affects the preservation of memory and identity within the Armenian diaspora. Influenced by scholars Ibtisam Azem and Marianne Hirsch, who explore themes of invisibility, identity, and memory in their work, I aspire for this project to transcend physical archives and examine memory’s influence on geographical landscapes. By digitally manipulating my grandparents’ photographs, I remove and obscure family members from within the images. The result of this is the creation of eerie, dreamlike landscapes where the memory of what once was continues to haunt the frame. Although no longer visibly present within the images, the memories of my family not only haunt the space within the photographs but also disrupt the present landscapes from which they were forcibly removed.

Follow Sophia on Instagram: @sophichia

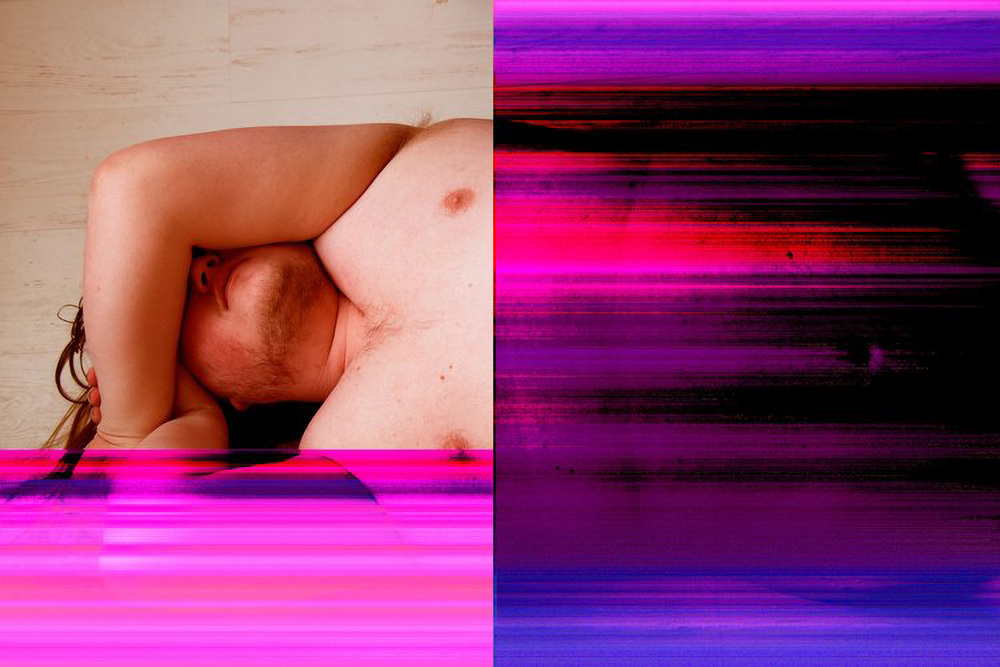

© Ash Huse, from the series DEADNAME

Ash Huse

Columbia College Chicago, MFA in Photography

I came out as nonbinary in 2021. It was a perfect, bittersweet storm of internal looking due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the isolation that followed. During this tumultuous time, I finally allowed myself to have a dialogue about my identity. I was so aggravated and frustrated with the world, angry at my art due to feeling powerless to help my current situation. I felt the desire to destroy, in a manner of speaking, the pristine art that I had focused on years prior. I discovered a way in which to databend my images, a form of corruption utilizing audio software. On the one hand, I was taking pre-existing images and destroying them, yet at the same time, through that destruction I was taking control back to create beautiful abstractions of noise and data. I was creating these abstractions without fully understanding why I had desire to do so, yet it began to be symbolic of my own path of identity.

Through my thesis, DEADNAME, I explore concepts of identity, queerness, self-image and mental health. By destabilizing photographic portraiture, I create images of my own body using music software, changing the code of digital files, and rephotographing images on screens. I investigate ideas of bodily metamorphosis by using a process of corruption and digital abstractions; moving past binary or traditional views in portraiture.

The chaos conveys a sense of anxiety and depression that has been attached to my own sense of queerness. I combine all of these elements in my work to have a larger discussion about my gender dysphoria and unease of not feeling wholly male or female, but nonbinary. This series showcases how both revealing and concealing the self can be an act of transformation. By performing for the camera and experimenting with distortion of these images, I seek out new ways to tell the story of how queer bodies can be a site of transformation and self-discovery.

Follow Ash on Instagram: @ash.huse

© Halima Ibrahim, from the series Listen to the prayers they sing

Halima Ibrahim

Stanford University, Bachelors in Art Practice (Honors) and Art History

Cairo’s landscape is rapidly changing as the government attempts to modernize Egypt. New bridges are appearing daily, blocking and rerooting traffic. Houses are being torn down to widen the highways. The colorful interior walls of family homes are the only surviving reminders of the residents lives before their displacement. Hundreds of tombs at the edges of the City of the Dead are being relocated to make room for new lanes of traffic. The City of the Dead is Cairo’s largest necropolis built circa 700 CE and houses the majority of Egypt’s dead. Struck by great anger and grief, Egyptians objected the demolition, arguing that the tombs were part of our cultural history and needed to be preserved. The government responded ‘Egypt’s history is as old as history itself, How old does something have to be for it to be counted as history worth preserving?’

Listen to the prayers they sing is a memorialization of the demolition of my city told through images of ruins and devotional graffiti. From Ancient Egyptian temples to unfinished buildings in new cities, Egyptians have always used walls as tools of worship. Walls are the protectors of our history, the keepers of our knowledge, the memorial of our dead, and the steward of our prayers. It is the walls that house and hold our lives. Walls can and do talk, as long as people are willing to listen. In a trip to the red sea with my family, I was captivated by the scribbled devotions on the frames of unfinished buildings. One day, the buildings will be bought by developers and a fresh coat of paint will cover the prayers. I thought about all of Cairo’s buildings hiding the names of God under layers of dust and paint. I imagined the prayers being shattered into ruins across the highways. The praises being released into the air along with the dust from the demolitions. Everywhere I turned, I heard the walls sing.

In grieving the loss of my city, I am meditating on the use of graffiti as an act of prayer and resistance. In the presence of violence I am brought to prayer. I have transformed the ruins of Cairo into my own canvases for worship. Within the rubble, I pray for the preservation of my country’s histories. I pray for my ancestors within their graves. I pray for the families relocated from their homes. I pray for the 1.9 million displaced Palestinians and those who are denied entry into Egypt. I pray to see the day my country stops worshiping the dollar. I pray that all the prayers written within the walls are answered.

Follow Halima on Instagram: @_lima.i_

© Alexander Iglesias, from the series I Love It Here, I Hate It Here

Alexander Iglesias

Rochester Institute of Technology, BFA in Photographic and Imaging Arts

I went to high school in Chattanooga, Tennessee and I am one of a handful of graduates from there who went to college, let alone left the state. I never wanted to leave, I wanted to stay at home and do drugs with my buddies like we always had. I got my first camera when I turned 16 and started taking pictures of my friends, which is how this project was conceived. Due to the encouragement of my high school photography professor and the fear when bodies started to pile up, I ended up leaving for college. I realize now I was really just running away.

My home has a hold on me, it is intertwined with who I am and chains me to it, if not physically at least mentally. It has constricted and constructed my identity and I’m only beginning to free myself from it. My friends who are alive are not so lucky, I’m one of the few to have escaped its grasp which is something I will forever feel guilty for. Many of them don’t seem too concerned about it and I guess that’s good for them, but I know it wasn’t good for me. I Love It Here, I Hate It Here is (roughly) our story, comprised of pictures from my personal history, reflective photographs from the modern day looking back, first person writings collected from myself and friends, and things that remain in-between. It is not a unique story, and I think I deserve a lot worse than I got.

Follow Alexander on Instagram:@alexander_d_i

© Joseph Ladrón de Guevara Coca, from the series Love Amidst Mortality

Joseph Ladrón de Guevara Coca

Centro de la Imagen, Visual Projects and Photography Certificate

Surely he took up our pain

and bore our suffering,

yet we considered him punished by God,

stricken by him, and afflicted.

Isaiah 53:4

Julia, my maternal grandmother, died one night in March, as a result of cancer with which she fought for a year. She decided not to treat her illness, as she firmly believed that her god would heal her. The end of her life —always guided by the Christian faith— took place while she sang her favorite choir, surrounded by her entire family.

Her death, the repercussions it caused on my family and the heavy sensation of absurdity that his blind faith imprinted on my understanding left me with many emotional conflicts and ideological concerns, which are the origin of this project and my proximity to this thematic universe.

Some months after her death, he decided to collect photographs from the family archives and from her religious congregation, as well as a series of notes from her notebook, which was written during the months in which she struggled with her illness. With this material I developed sets that seek to be an exploration of the emotional, mental and ideological changes that this disease caused on her and on her family, in general. This first part of the project, rather intimate, made me see the dimensions and directions that the theme could reach, and think of other ways of materializing it.

The second part is about a documentary photographic approach, with a rather contemporary nuance, through which I seek to answer questions such as ‘How far can someone go by faith?’ or ‘what do those who believe believe?’, and, at the same time, pointing to what happens in these spaces, their beliefs and their worldview, based on the experience of my family and their congregation, and extrapolating it to that of the people that make up these groups and lead this lifestyle.

In this way, this project seeks to propose an intimate approach to the Christian faith, its vicissitudes and the way of thinking of its believers, often complex and radical, and other times beautiful and hopeful. I intend to confront the viewer with the same absurdity that invaded me when I saw my grandmother let herself die for faith, but also with the small luminous episodes full of illusion that appear in between.

As someone who grew up in a strongly believing family, and making use of the various visual resources and supports that I have been exploring, I seek to generate a realistic view of the subject, but not one that acts as a typographical mirror of what happens, but rather as an alchemy that allows us to observe below its causes, its motors, the reasons that lead people to surrender to the faith, to live it and die it, as my grandmother did.

Follow Joseph on Instagram: @josephlgc

© Matthew Ludak, from the series Nothing Gold Can Stay

Matthew Ludak

University of Wisconsin at Madison, MFA

Nothing Gold Can Stay is a documentary photography project that takes a closer look at how economic globalization has left its mark on former industrial cities and struggling small towns across America. Inspired in part by my own family history of living and working in a small mining town in Wester Pennsylvania, this project delves deep into the intricate tapestry of economic desperation, resilience, beauty, and transformation that defines these often-overlooked corners of society. Additionally, the project aims to draw attention to the environmental impact wrought by the steel and coal industries, examining the lasting consequences on the landscapes and communities that once thrived alongside these industrial giants.

The protagonists of the project are the small towns and rural communities that once hummed on the pulse of factories, mills, and mining. Nothing Gold Can Stay examines the interplay between economic shifts and the lives of those who have weathered the storms of change.

At the heart of this work lies an exploration of the fleeting nature of beauty and the unwavering resilience of individuals in the face of adversity. The title itself, borrowed from Robert Frost’s poem, encapsulates the essence of impermanence that underpins each photograph. Image by image, the project seeks to capture the timeless essence of these communities, revealing a quiet beauty in the still moments of everyday life.

Streets once bustling with life now stand deserted, buildings once humming with activity now echo with silence, and rusty cars become relics of a vanished time. The photographs serve as an ode to the symbiotic relationship between physical space, culture, and history, offering viewers a glimpse into what make these places unique. By focusing on the present state of neglected areas, we are reminded of their once-idealized pasts. The worn-out parking lots, forgotten homes, empty storefronts, and abandoned factories stand as symbols of an America that has evolved over time.

Ultimately, this project serves as a reminder that within the ruins of the past lie seeds of renewal and growth. Nothing Gold Can Stay implores us to cherish the moments of quiet beauty that remain amidst the march of progress, and to honor the resilience of those who have faced adversity with unwavering grace.

Follow Matthew on Instagram: @ludakiewicz

© Lydia McNiff, from the series Visceral

Lydia McNiff

Illinois State University, Bachelors

A question I find myself frequently returning to when it comes to soul creation is what shapes the human mind; in specific, how does trauma and hardship play a role in how one views their own personal life and the world around them. I try to answer this extensive question through the analysis of my own personal life journey in hopes to open doors for a safe space of communication. Everybody has their own version of life trauma and the ways in which they cope with it; mine just happens to be surrounding vaginal health. My photographic work is both analytical and deeply personal in a sense that it displays a personal life journey of being diagnosed with vaginismus, pcos, and genital labial ulcers in addition to commenting on a broader range of societal misconceptions behind gender roles and the importance of vaginal health.

Vaginismus is the uncontrollable contraction and spasm of the muscles surrounding the vagina which requires daily treatment such as pelvic floor physical therapy and the use of dilators. Pcos is a common hormonal problem that creates cysts on the ovaries and is known to cause daily pain, ovulation problems and can prevent the possibility of pregnancy. Genital labial ulcers are any type of lesion or open wound found on the vulva and are what landed me an extended stay in the hospital.

My work explores various topics surrounding vaginal health such as the menstrual cycle, pleasure through sexual activities, and various gynecological medical battles along with their treatments. I work with digital photography to document my own personal treatment and medical processes as well as my emotional journey in hopes to spread awareness on this topic as well as provide an outlet for myself to process my thoughts and emotions. My work is both complex and direct in a sense that I aim to juxtapose the opposing sides of vaginal health; those being, the medical and sensual. Still lives make up the majority of my work but I also work with self portraiture. To highlight this juxtaposition; both of these compositions as a whole contain a combination of both sensual (red, pink, black) and sterile or clinical (blue,gray,white) color palettes. When viewing my work, a spirit of inquiry and close study is encouraged through the usage of visual metaphors as well as unique hand picked items such as gynecological tools or common feminine products, which can all be classified as challenging subject matter. I hope that this body of work sparks a desire of discovering and learning about vaginal health as well as rewriting its narrative of being a taboo topic of discussion. The goal of the work is being achieved simply by placing these images in front of people; by forcing them to at least be aware of their existence.

Through photography I am able to express how my own personal health journey has shaped me as a person and can hopefully normalize vaginal health problems by turning them into strengths versus weaknesses. My work aims to convey that everybody goes through their own versions of trauma whether it is medically related or not and the ability to understand how these traumas shape the human mind is an equal parts magnificent and challenging undertaking.

Follow Lydia on Instagram: @lydiamcniff_photography

© Mehrdad Mirzaie, from the series Imago

Mehrdad Mirzaie

Arizona State University, MFA in Photography

My practice is characterized by working with a diverse array of historical images, whether through the curation of new archives or the reinterpretation of existing ones. I firmly believe in the transformative power of historical imagery to inform our present and shape our future. By scrutinizing historical images and the mental images they evoke, I aim to challenge conventional interpretations of the past. I investigate how various contexts and audiences, each with their unique backgrounds, can influence our understanding of history.

I use historical imagery as a means of reevaluating and reconstructing our collective memory. I define my role as a storyteller, weaving together various narratives and visions from the past and the present to foster a deeper understanding of the world we inhabit. Through my practice, I seek to prompt reflection, provoke questions, and encourage viewers to reconsider their preconceived notions of history and its impact on our lives today.

These days, I am working on an archive that includes images of people who disappeared or were killed because of the religious, ideological, and political ideas of the Islamic Republic regime in my home country, Iran. The focus of this project is on events from 1979 until now. This archive will include thousands of images. The images will be extracted and reproduced (reread) from various archives and sources.

Follow Mehrdad on Instagram: @mrdadmirzaie

© Anh Nguyen, from The Kitchen God Series

Anh Nguyen

International Center of Photography

In Vietnamese popular mythology, every family is said to have three kitchen gods that reside in their house. Altars are typically placed by the stove so the gods can always watch over to ensure family members treat each other well and all matters of the home are in order.

The Kitchen God Series explores the imaginative landscape of myth by looking at how young Vietnamese people create homes of their own in New York City. By unpacking cultural rituals as performance, I am interested in how my generation finds ways to make traditions part of our own lives.

Somewhere between reality and fantasy, my approach to documentary questions the sometimes absurd confines of identity through playful interventions into observable events and relationships.

Removed from its original context, traditions inherently become conceptual and open to interpretation. This is true of how the Kitchen Gods’ origin story is remembered, and it is true of how we perform rituals involving food — everything from setting up for family meals, to creating offering tables for our ancestors.

Follow Anh on Instagram: @minhanhnguyenn

© Mosfiqur Rahman Johan, from the series Memories of Underdevelopment

Mosfiqur Rahman Johan

Counter Foto Centre for Visual Arts

Spending childhood and adolescence in my grandparent’s house, I only got warmth from that place. Not just from one house or a yard, but from a whole village. Now, when I go back to that Morichbunia village, I only get the heat of development which ruined the land, the economy, the people’s last asset, and everything possible.

Payra Power Plant Project started in 2014, and since then the Dhaankhali Union of Bangladesh has been facing ruins every day. Visibly the loss was only of lands. But losing lands also changes shelter, culture, agriculture, memories, kinship system, and even identity. Where home is by default connected to identity, this process of changing the ownership of lands can’t be separated from the local politics of cultural inclusion and exclusion. Apart from human life; the ecosystem, local plants, rivers, and other animals are also the victims of this destruction. The community ultimately didn’t even get the promised jobs, homes, land, or proper compensation.

A large number of people shifted, leaving their ancestral houses behind. The houses and lands are there, but those who were supposed to bring the life there don’t exist there anymore. This mega project left the land with the elegy of memories. While looking at the traces of development with migrational trauma in their head, people in my hometown now see only the dust and dense air of coal-based power plants.

Memories of Underdevelopment delve into the complexities of identity, belonging, and loss experienced by individuals whose homes have been transformed by large-scale development projects, highlighting the profound social, cultural, and environmental consequences of such endeavors.

Follow Mosfiqur on Instagram: @mosfiqur

© Emma Ressel, from the series Glass Eyes Stare Back

Emma Ressel

University of New Mexico, MFA in Photography

In my photographs, I nod toward the precarity of our damaged ecosystems and my fears about environmental catastrophe by looking closely at the eerie magnetism of preserved animals. To make my images, I position specimens and printed backdrops before my camera to construct still life tableaus that I call fictional habitat dioramas. Some of the backdrops contain imagery of wildfire-smoke-filled skies or Hudson River School paintings that romanticize and fictionalize the landscape. These images demonstrate not only my fear about our environmental futures, but also a sense of sublime awe about the mystery of what’s to come.

My pictures argue that animals preserved for science occupy a third space between life and death—neither alive nor gone, but still functional and serving a purpose. A second life in a museum hall is much longer than the first. Taxidermy is an antiquated method in which an animal is stuffed and posed to perform itself. Animal specimens in research collections, on the other hand, gesture toward the future. Biologists actively collect, process, and catalog species and store them in archival facilities to use in studies that will ideally—hopefully—help answer some of the existential questions we face about the future of biodiversity.

Like photography, animal preservation distorts time and creates an approximate experience. Collections in natural history museums and research facilities speak to our human desire to draw nature closer and to create encounters with animals. From our awkward place existing both within and outside of the natural world, we long to be connected with the things we are destroying. The fact that the animal must die in order for us to learn from it and witness it in proximity is a twisted irony. With my camera, I seek to fulfill my urge to witness nature in proximity, as well as question my desire for that proximity. Both in terms of large format film photography and animal specimens, this work is about things slipping away and our gestures to hold on.

Follow Emma on Instagram: @emma.ressel

© Quincey Spagnoletti, from the series Home Studio

Quincey Spagnoletti

School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University, MFA

When I look back at my childhood and how I was raised I am confronted with ideas and notions on how a woman is supposed to act and “perform” for society. Through my pictorial and arts-related explorations of womanhood, I strive to push back against the traditional norms that have dominated my upbringing, in the process highlighting the challenges of my own internalizations of a women’s role and my attempts to disrupt and unlearn what I have inherited.

Beginning with personal narratives and conversations with the maternal figures in my life, I set out to construct my own perception of space, and inheritance, based on memory. I incorporate human-scaled objects and props, the stuff of childhood and growing up, to ornament this investigation of perception. It is my intention to have the viewer question my intentionality and awareness, to wonder about where I am situated in the narrative of the work.

The nature of control continues to be a recurring theme in my work. Whether it is in searching for the “ideal” model, an exact replica of a leather chair or a childhood dollhouse, I use the camera as a tool to elucidate my own emotions and my relationship to myself and those closest to me. My current studio practice is a back-and-forth between pathos and this notion of control – a constant search for who I am as a woman and how I want to present myself to society. In this way, I hope to leave an inquiry of the matriarchal and the matrilineal for the generations to come.

Follow Quincey on Instagram: @QuinceySpagsPhoto

© Leni Wiegand, from the series The Whole Preposterous Ideology

Leni Wiegand

Indiana University, MFA in Photography

Work needs to be done to make the world a more accepting place for trans people. The falsely accepted norm of the gender binary needs to be dismantled, particularly in the face of growing anti-trans sentiment and legislature. It’s no longer ok for people to stand by as our safety and rights to live are stripped away. Through my work, I seek to educate about the tribulations of those who dare to live beyond the binary.

I show these struggles by utilizing the very texts of the laws that seek to take away my rights. Picking key lines that highlight the more heinous and often ridiculous aspects of transphobia. These snippets of laws are combined with photographic self-portraits of my own transitioning body with the databending process, defying the canon of what bodies should be shown. In databending the binary code of the files themselves is modified using non-traditional editing programs, this proverbial and literal breaking of the binary results in visual glitches.

The glitches that result from the forced modifications the file goes through when databending matches the struggles and scars left behind by those forced to go through the incorrect puberty. In a way, it leaves us glitched from the trauma we faced growing up in a body that felt unnatural to us. These glitches show the difficulties trans and non-binary people face as we are forced to navigate a society that not only expects but strictly enforces the gender binary. We must stretch, modify, and hide our true selves to avoid being erased and deleted from society, to avoid being “fixed” like the glitches we are seen as.

Follow Leni on Instagram: @leni.film.photo

© Zhou Yang, from the series Faërie

Zhou Yang

Birmingham City University, PhD

My ongoing project Faërie seeks to explore the space of traditional Chinese literati gardens. As a form of spatial imagination, time seems to work differently within and outside the gardens. A thousand years could have passed in the real world while merely a day in the gardens. Especially, the literati gardens after dusk seem a totally different world from the noisy tourist destination during daytime. In collaboration with the Ruan Yisan Heritage Foundation in China, I’ve gained special access to the gardens after the public opening time. The garden space in the dark is both enchanting and eerie. It is in such space where numerous stories featuring fairies, ghosts and Immortals happen in the classical Chinese literatures. While I walk in the gardens in darkness, with only my torchlight, I feel that every plant and stone are more alive.

In this project, multiple discourses are touched upon, such as the man-made vs. the natural, and meditation on mortality. The literati gardens were not a representation system in which the man-made mimicked the real hills or lakes in Nature. Rather, the intellectuals of dynastic China who built them, were Sub-Creators of a Secondary World, in the same way, as J. R. R. Tolkien argued, that fairy-story authors create a Secondary World, a Faërie, that follows its own law, free from the domination of observed ‘fact’, and into which our mind can enter and find Escape and Consolation. The garden is a three-dimensional Secondary World, into which we can physically enter, and Escape, not only from the old or modern ‘real life’, but more importantly, from the ultimate Doom: Death.

Photography as a medium is associated with the act of revealing as well as creating. In the gardens, I try to transform the noisy tourist attractions that the gardens have become today into images of mysterious realm, each on one single negative. The photographic images help us to look beyond the material world and find this hidden Faërie, beautiful but illusive, forever an object of human desire. The truth claim still associated with analog photography transforms my creation into belief of such Faërie’s existence.

Follow Zhou Yang on Instagram: @zyfotos2

© Shuyuan Zhou, from the series My Great Grandmother, My Grand Aunt, My Grandmother, My Mother and I

Shuyuan Zhou

School of the Art Institute of Chicago, MFA

The story starts with my mother. After she was born, her biological parents threw her into a bathtub and left her to drown. After being rescued, she was sent to her uncle’s home to be a child bride for her cousin.

Mom’s aunt, also a child bride, was given away fifteen days after she was born. I never knew her name. On my great-grandmother’s tombstone, my grand-aunt’s name is “Wu Cheng”, Wu being her adoptive father’s surname and Cheng being her biological father’s surname; people in the village call her “Chaolin’s wife”, Wu Chaolin being my grand-uncle’s name; and I call her “Grandma Yu Qiao”, Wu Yuqiao being the name of my cousin, who is also her eldest grandson. Every moment of her life is represented and told by men.

Grand-aunt said, “All the girls in the village had to be sent to other people’s homes like this. If you manage to raise her, she’ll become your daughter-in-law, but if you can’t, just leave her there for death.”

Except for one girl, my grandmother, who is my mother’s biological mother. My great-grandmother couldn’t have another son, so they gave my grandmother a boy’s name and raised her as a younger son in the family. My cousins call her “Er Ye”, which means “the second grandpa” in our dialect.

I think that’s why my grandmother tried so hard to have a second son after she got married. She first tried to drown my mother, and then strangled my mother’s younger sister to death with her own hands. Then, my mother’s younger brother was born, carrying the tragic fate of two sisters and meeting the expectations of the whole family.

When my mother was ten, it dawned on the adoptive parents that close relatives cannot get married, so she was ruthlessly sent back to her biological parents. She was malnourished, did not speak Mandarin, and was an extra mouth to feed in the family. What awaited her was nearly a decade of being bullied, used as a babysitter for her brothers, and deprived of education. But she has survived.

The trauma of patriarchy on women passes on from generation to generation. Grand-aunt says she will spend the rest of her life hating her parents for sending her away. Grandma never went back to visit her mother although her mother has passed away for more than two years. My mother would get teary-eyed every time she mentioned her childhood experiences. And I am still trapped in this traumatized mother-daughter relationship.

In this work My Great-grandmother, My Grand Aunt, My Grandmother, My Mother, and I, I revisited the histories of my female elders where I recreated scenes from the lives of four generations of women in my family and represented this narrative in a dramatically vivid way. By introducing a private interpretation of historical events and family traumas, and adding photographic intervention, I created a new degree of reality, a potentially more plausible, yet fictional world.

By using photographic interventions, I want the audience to be aware that there is an “I” beyond the camera. What role do I play? As a victim of intergenerational trauma, I pass on this damage between women, but my existence is also a reflection of social progress and female empowerment. Extending the photograph beyond the camera and emphasizing “I” as part of the photograph is essential to my work. My very existence can be one of the meanings of this project.

Follow Shuyuan on Instagram: @shuyuan.zhou.art

© Andrew Zou, from the series Gazed Gaze

Andrew Zou

Massachusetts College of Art and Design, MFA in Photography

Raised in a conservative society where discussing sexuality is taboo, I place myself on the edge of these restrictions to test my limits. Through these photographs, I explore my sexual identity, desires, intimate relationships, and fetishes. Inspired by a Chinese poem, “When you look at the landscape from a bridge, you become part of the landscape for people looking from above,” my work explores self-observation through self-portrait, still life and others. It creates dual role as subject and viewer, engaging me in a mutually gazed gaze.

When photographing myself in private spaces, I create an intimate relationship with my queerness within a space of self-protection. In outdoor spaces, I project my consciousness onto the world, maintaining a connection with my surroundings and drawing energy from nature. Utilizing online dating apps, I encounter people who bring unpredictable experiences and insights, allowing me to explore fetish through all five senses. By layering Chinese calligraphy, photography, and performance, I highlight the tension between my Chinese cultural heritage and my individualism. A significant moment I capture involves shaving my hair, symbolizing transformation and liberty.

Follow Andrew on Instagram: @andrewzouaijun

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2024 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner: Natalie ArruéJuly 28th, 2024

-

The 2024 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner: Joseph Ladrón de GuevaraJuly 27th, 2024

-

The 2024 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner: Andrew ZouJuly 26th, 2024

-

The 2024 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner: Anh NguyenJuly 25th, 2024

-

The 2024 Lenscratch 3rd Place Student Prize Winner: Mehrdad MirzaieJuly 24th, 2024