Photographers on Photographers: Brayan Enriquez in conversation with José Ibarra Rizo

Photographers on Photographers is our annual August effort where we ask photographers (including the Top 25 Winners of the 2023 Student Prize Awards) to interview an artist or mentor that has impacted or inspired their practice.

I first met José Ibarra Rizo at his second solo exhibition at Mint Gallery in Atlanta, GA. At the time, I was still in my undergrad studying photography, and it was through that program that I got to attend José’s tour of his show, The Price of This Dream, which discussed his family’s complex migration history from Mexico to the United States over the last forty years. Having worked with similar themes, I was eager to introduce myself and forge a personal connection with the man behind the photographs that resonated so deeply with me. That was over a year ago, and I still have yet to find an end to the many threads of conversation we tugged loose that day. Still, from time to time, we give it a shot—which is exactly what we are doing today as José takes me on a tour, driving us towards the trailer park his father once called home.

José Ibarra Rizo (b. 1992) is a Mexican-American artist based in Atlanta, GA. His work explores themes of identity, particularly focusing on the migrant experience in the American South. Rizo is the recipient of the inaugural MINT + ACP Emerging Artist Fellowship, one of three awardees for the 2022 Atlanta Artadia Awards, and a 2023-2024 Working Artist Project Fellow for the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia. His work is housed in numerous collections including the High Museum of Art, the Virginia Museum of Fine Art, and The Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory University. Rizo’s clients include publications such as Rolling Stone, The New York Times, and TIME Magazine.

Instagram: @joseibarrarizo

We drive past a teenager who reminds me of my little brother just as we enter a neighborhood scattered with trailer homes. José slows down as we spend some time looking at each home dense with history and character.

Brayan Enriquez: So, tell me about the area.

José Ibarra Rizo: I spend a lot of time photographing these places. This particular area is special in the sense that Suburban Mobile Home Park was the first place where my dad and uncle lived.

BE: How long ago was that?

JIR: I want to say that was the late 1990s. They made their way here after hearing about the poultry industry. My dad and his older brother, my Tío Polo, lived in one of these trailer homes. My uncle can’t seem to remember which one it was for some reason.

BE: Oh, so these are practically unchanged, huh?

JIR: Yeah, not much has changed. I don’t know if you remember my photograph of a guy on a bicycle. I made that image right here.

BE: Is returning to these places important for your practice?

JIR: I think so. At first, I was just doing it naturally, but then I watched this video of Todd Hido. He said, “Why don’t you just go back to the places that gave you those nice moments and keep digging?” I’m also just interested in learning about the environment and the people here. Just observing–that’s really important to me.

BE: And this is pretty close to where you currently live, right?

JIR: Yes, everything is super close. Up there is where my uncle, the older one, lived. The one that kind of brought everyone here. Encouraged everyone to come here.

BE: How did he come over here, if I may ask?

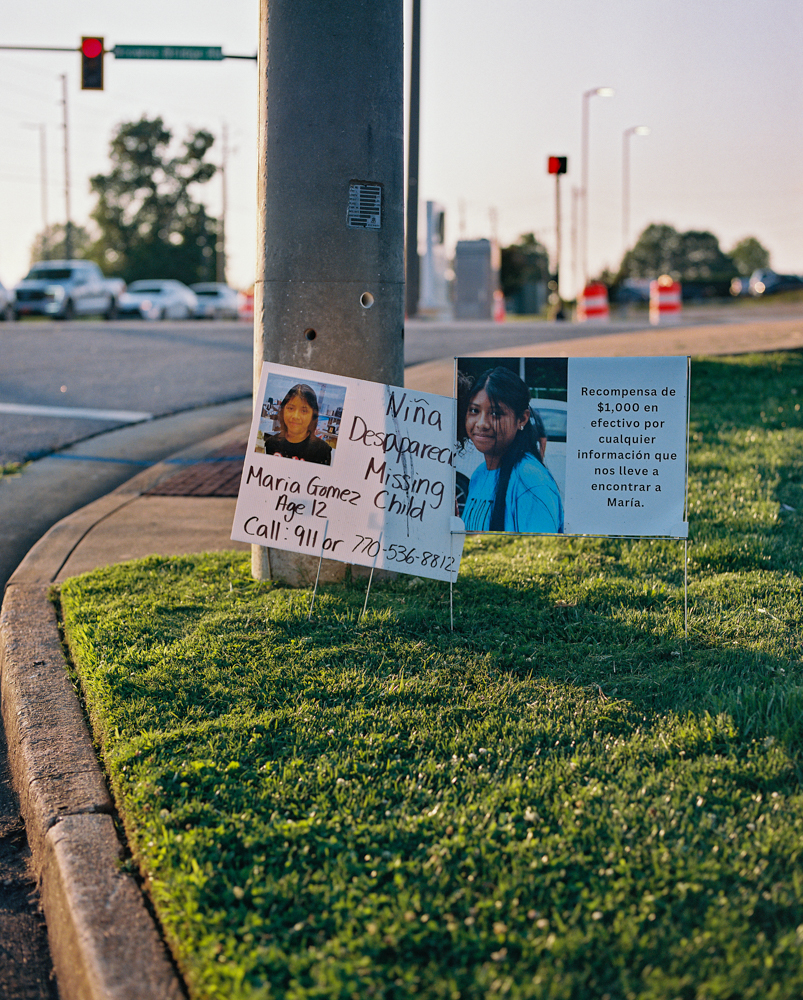

JIR: I’m not quite sure how he heard about Gainesville because they were all previously in California. They were working the fields over there picking avocados, oranges, you name it. He used to live in that apartment complex over there. Then, you know, they all started doing their own thing. Purchasing their own homes. There are other areas around here that I’ve been photographing throughout the years. Maria Gomez-Perez, the little girl who disappeared, lives right across the road actually.

BE: Really?

JIR: Yeah, I can show you.

José turns the car around and starts to drive away from this more personal scene, passing pedestrians who almost look like family. As we’re driving, our surroundings quickly shift from mobile homes to small, one-story houses as we make our way to Maria’s family home.

Maria Gomez-Perez is a twelve-year-old girl from Gainesville, GA who went missing on May 29, 2024, when she was last seen near her house on Westside Drive. During Jose and I’s conversation, Maria was still missing, but thankfully, as of July 25 the Hall County Sheriff’s Office announced they’ve safely located and recovered Maria in another state.

BE: I saw that you’ve been making photographs about that situation. I can’t even imagine what her family is going through.

JIR: Yeah, it’s very sad. It seems like this epidemic of missing girls from our communities continues to get worse. And it’s home too, you know.

Soon, I catch sight of one of the many missing person signs for Maria Gomez-Perez that can be found all over Gainesville. The sign sits in the front yard of Maria’s family home: a house with a faded red roof and a child’s book bag hanging out front. José and I share a quiet moment as he continues to drive.

BE: So, would you say that your photographs are as much about place as they are about people?

JIR: Absolutely. I think with time, this project has evolved to be more about place and about the symbols that I see recurring.

BE: If you could, what symbol do you think–

JIR: The corn. The corn is what’s tying this project together, among other things. I made an earlier image when I started this project of this guy watering his corn in a suburban neighborhood. To me, it serves as a reflection of how we occupy space, and how we use land, but corn is also indicative of Latino culture. So that guy, a Salvadorian, and a lot of Guatemalans do it too, they plant these crops up against their houses and then FaceTime their family members back home to show them. It’s a way for them to bridge that distance, that gap.

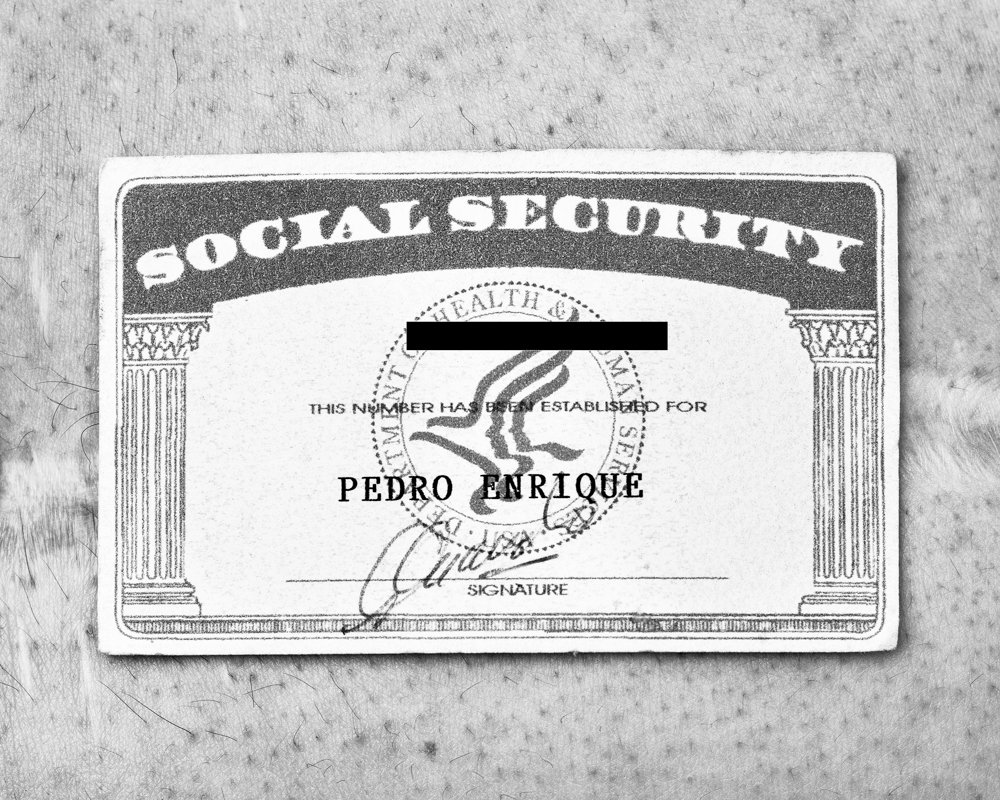

BE: Speaking to that distance, you actually immigrated here as a child.

JIR: That’s right.

BE: Can you speak a little bit about that?

JIR: Yeah, I came here with my mother as an undocumented immigrant in 1999. I want to say she was twenty-seven or twenty-eight years old. I was seven. My dad was already here. I like to think about my life Before and After as these two very different chapters. One’s very blurry and hazy, and then coming here, to America, to the South, I had to practically reinvent myself. I had to learn a new language and a new culture. I’d say that’s the starting point for the work I make. A lot of the people in my community, particularly the ones that I’ve been photographing in recent years, are new immigrants, so sharing that common ground and connecting on that and on labor is a big component of this project because I’ve been very blessed. I’ve had a good education. I’ve never lacked a meal, but I’ve also worked in many of the jobs that are available here. I’ve worked in the poultry factory. I’ve worked in landscaping. I’ve worked in restaurants washing dishes. That’s how I’m able to connect with them and have a comprehension of what their day-to-day is, but there’s also this gap of privilege between them and me that I’m conscious of, too.

BE: And your family back in Mexico. Do they know that you’re an artist, a photographer? How do they perceive your work?

JIR: I think it’s not until recently that my family’s comprehending what it is that I do. What about you?

BE: I would say that’s sort of the same thing with me. It wasn’t until someone else wrote about my work that my family started to take my work seriously.

JIR: No absolutely, and it’s a different world for them, right? They didn’t grow up with things like that. I think the younger generation of my family comprehends what I do, but lately, with the opportunities I’ve gotten, my parents are finally understanding what it is I’m doing. With other family members, it’s just kind of like… you know, people tend to simplify what it is that we do.

BE: Yeah, photography is really accessible so I think it’s hard for a lot of people to view the medium the same way they would with painting, a medium you actually started in.

JIR: Yeah.

BE: You speak a lot about how your now-fiancée introduced you to photography. You both are great photographers, but I’ve noticed that the kinds of photographs you each make are very different. She operates within a commercial context, whereas you’re occupied with placing your work in museums and galleries. As someone who’s self-taught, how did you formulate the photographic vocabulary that you now use?

JIR: Yeah, good question. I think… oh, this is where my mom works.

BE: Oh wow, so this is the poultry factory.

José stops the car. Before he has the chance to answer my question, the poultry factory speaks for itself. Here is José’s vocabulary: the people, places, and work of daily life. As we gaze up towards the large, cream-colored building, we find ourselves caught up in the factory’s self-contained community of traffic: shipments and nondescript semi-trucks obstruct our path.

JIR: My dad works at another poultry factory that’s forty minutes away. Anyways, art has always been a passion of mine, as early as I can remember. It’s true, I’ve studied painting more than I have studied photography. In college, my background was in drawing and painting, so studying paintings and composition and the use of color has helped inform the way I compose an image, the way I make an image, how I treat color. Even though I don’t have formal training in photography, I think those disciplines kind of inform each other. Or, at least, having that background has helped me understand the principles of what makes a good photograph. Now my challenge is learning the ethics of photography: the relationship of a camera with my subjects. Studying that relationship has been key in both comprehending my work and my responsibility with the work that I’m making.

Once the flow of factory traffic offers some relief, José drives us away, proceeding with our tour.

BE: What kind of work were you making back then as a painter?

JIR: I think my painting days were filled with a lot of exploration. I wasn’t making a series about this or that, but I was always leaning into the portrait and exploring color and compositions. Bright colors have always been a part of my visual vocabulary, and I think that just comes with being Mexican. Back home, color was everywhere. It’s not as stale as it is here in the States, where most homes are painted white, for example. I think, subconsciously, that kind of informs my color palettes and the way I like to approach photography and painting.

JIR: I think the problem with painting for me and why I started leaning away from it was because I painted slowly, actually. I’m a really slow painter, and it messed with me mentally, so making images through photography was a way to create faster, digest them, think about them, process them, to then inform what needed to be made next. I essentially love to tell stories, right? That’s my passion, so whether it is through a painting or a photograph, that’s the ultimate end game of my work.

BE: I’ve also heard you talk about how you’d struggle to make art during your painting days, and yet, it seems like you’re constantly making new photographs. Maybe that is connected to the process and how photography lends itself to be quicker, but is there something other than the speed that photography gives you that you don’t get from painting?

JIR: Yeah, absolutely. I think it’s both photography being a solution to a problem as well as the timing. It just so happened to be that the moment I realized what kind of work I wanted to be making was also the time that I was finding the medium that I wanted to work with.

José parks in front of a small, fenced-in basketball court. I look around and notice we’re back in a residential space, but I’m not sure if this is the same neighborhood as before. Community members have gathered outside to rest, share meals, and otherwise enjoy each other’s company.

BE: Is this a place where you’ve photographed as well?

JIR: Yes, in that parking lot I photographed KP, the girl with the skateboard.

BE: I see how you’re able to find people to photograph, it feels like everyone is outside over here. I imagine you get asked a lot about what it’s like when you photograph people you don’t necessarily know. People can be quite alert to outsiders in their community. I don’t know, do they ever see you as an outsider when you approach them with a big camera?

JIR: Sometimes there’s some of that. Sometimes I get jokes like, “Oh, it’s for TikTok,” but I always try to find common ground.

BE: There definitely is common ground. I mean, you literally live two minutes away. You’re a part of this community. I just think it’s interesting how a camera can make someone seem like an outsider even when they aren’t.

JIR: Sometimes I don’t even have it on me when I ask people. Sometimes I approach them and just start a conversation or explain to them the project that I’m working on. Then I’m like, “Hey, would you be interested in being part of that?” and I’ll either get a yes or a no. It’s really important for me that the people I photograph have comprehension of what I’m doing. I’m not just taking an image and walking away. It’s just kind of like, okay, cool. Who are you? How did you get here? What do you do?

BE: How often do you run into the people that you photograph? Do you see them again and again?

JIR: Yeah, sometimes. The other day I was running on a trail that I frequent, and I bumped into one of the guys from my photograph where they’re prepping tamale leaves. I saw him and asked how he was. Turns out that the other guy featured in the image did him wrong, and it went sour. It’s so interesting that this image that I had of them now feels different after my re-encounter with one of the subjects.

BE: You said earlier how art has always been a constant for you. Was there someone who helped bring art into your life, or was that something you just stumbled upon?

JIR: I think creativity has always been in me. I was very fortunate to have spent a lot of time with my mom. My dad was always here in El Norte, working. My mom has always been very good at nurturing anything she saw that I would excel in or saw that I had a passion for. But in terms of someone introducing me to art, I don’t have a clear picture of that. I’ve just always found myself to be creative, whether it was painting or drawing something, creativity was something that I’ve always felt in me. It wasn’t until I was in my late teens in high school that the idea of this becoming a career or being a reality felt possible. In college, meeting some mentors that I still hold dear as friends also really helped me see that this could be a reality for me. Not so much the creative part, but rather this being a lifestyle, a career one can pursue. Those early college years were fundamental to where I am now since I was able to avoid the usual “Why would you ever pursue that? There’s no money in that. Your parents brought you here for that?” I was very privileged and blessed to instead be around very nurturing individuals. To be around people who helped push me to believe that I could do this despite my background, despite my history.

Brayan Enriquez (b. 2000) is a first-generation Mexican-American artist based in Atlanta, Georgia. His work focuses on his immediate family and their history of being undocumented to discuss the migrant experience in the United States. Enriquez earned a BFA in Photography from the Ernest G. Welch School of Art and Design at Georgia State University. He’s a recipient of the Atlanta Center for Photography Equity Scholarship and The Larry and Gwen Walker Award, was shortlisted in the 2024 Sony World Photography Awards, and has been featured in LENSCRATCH and MATTE Magazine.

Instagram: @_brayanenriquez

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

Ben Alper: Rome: an accumulation of layers and juxtapositionsJanuary 23rd, 2026

-

The Next Generation and the Future of PhotographyDecember 31st, 2025

-

Aaron Rothman: The SierraDecember 18th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Congyu Liu in Conversation with Vân-Nhi NguyễnDecember 8th, 2025