Ryan Peter: Autograms – The Intersections of Drawing, Painting, and Photograph

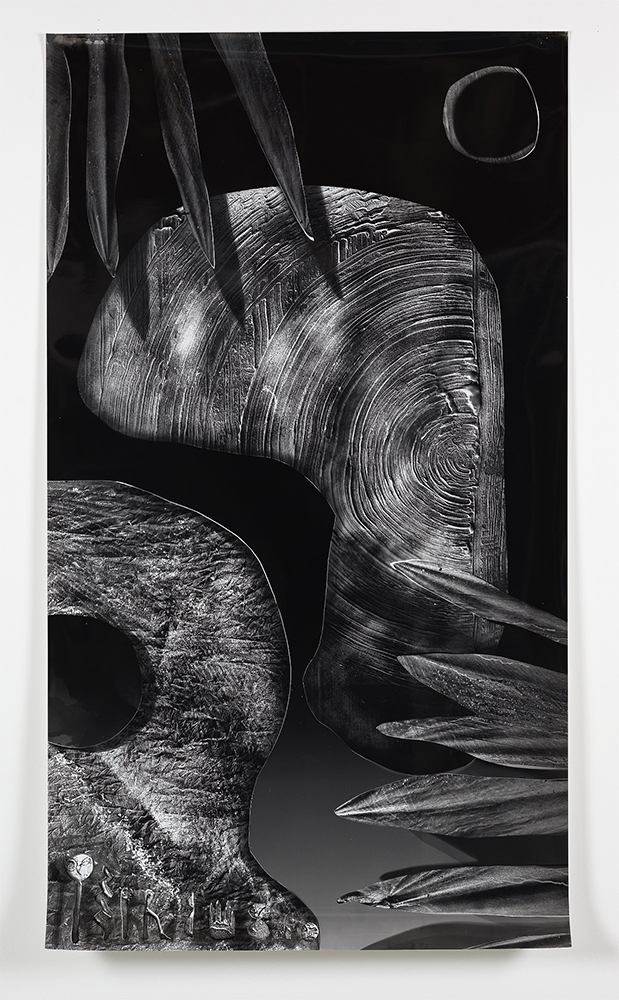

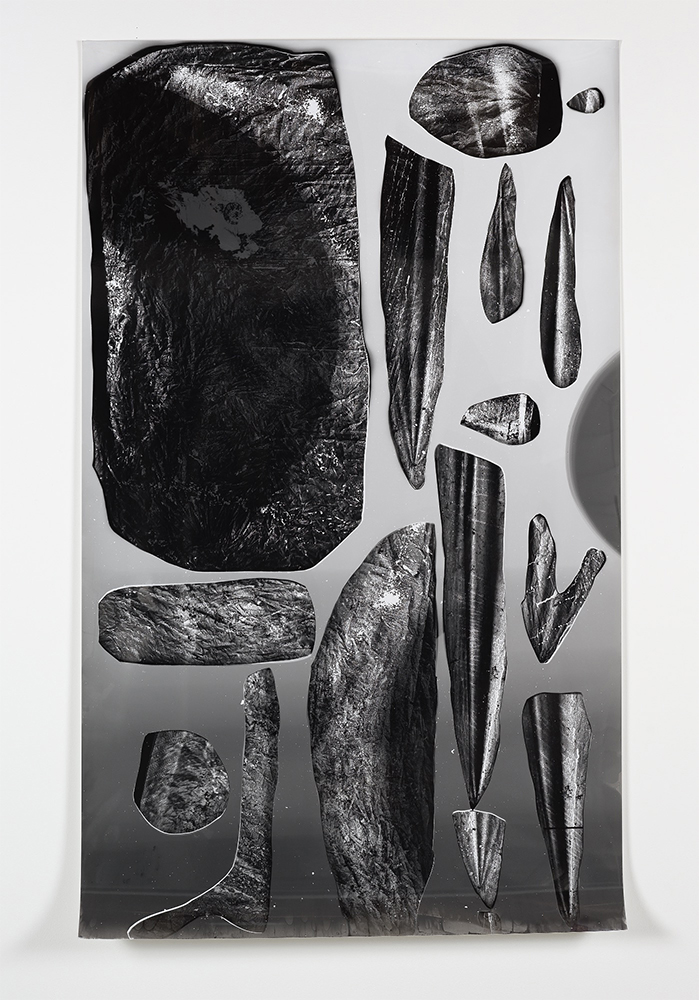

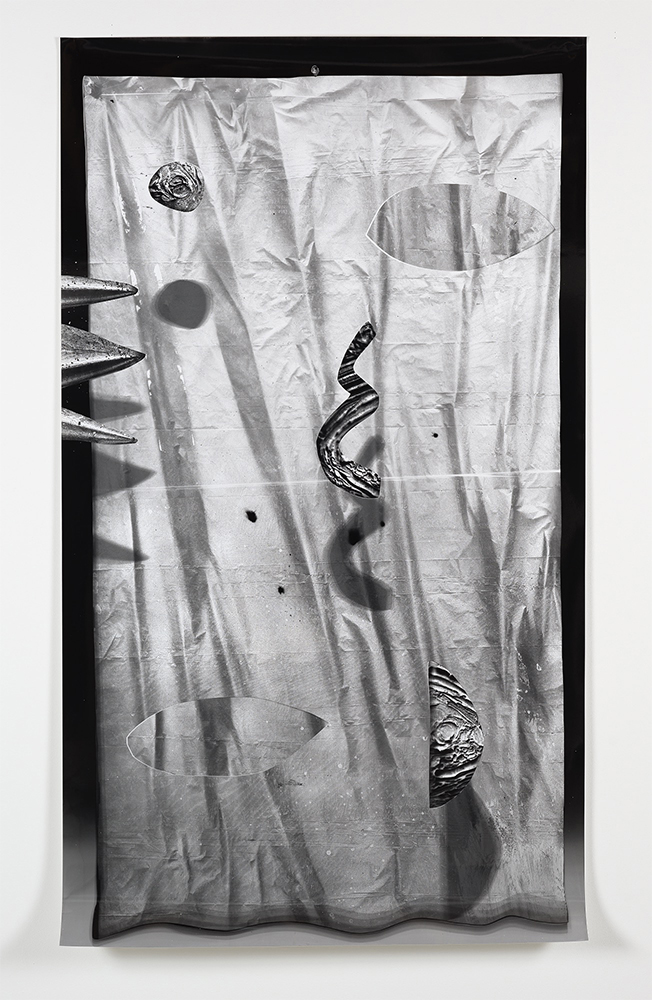

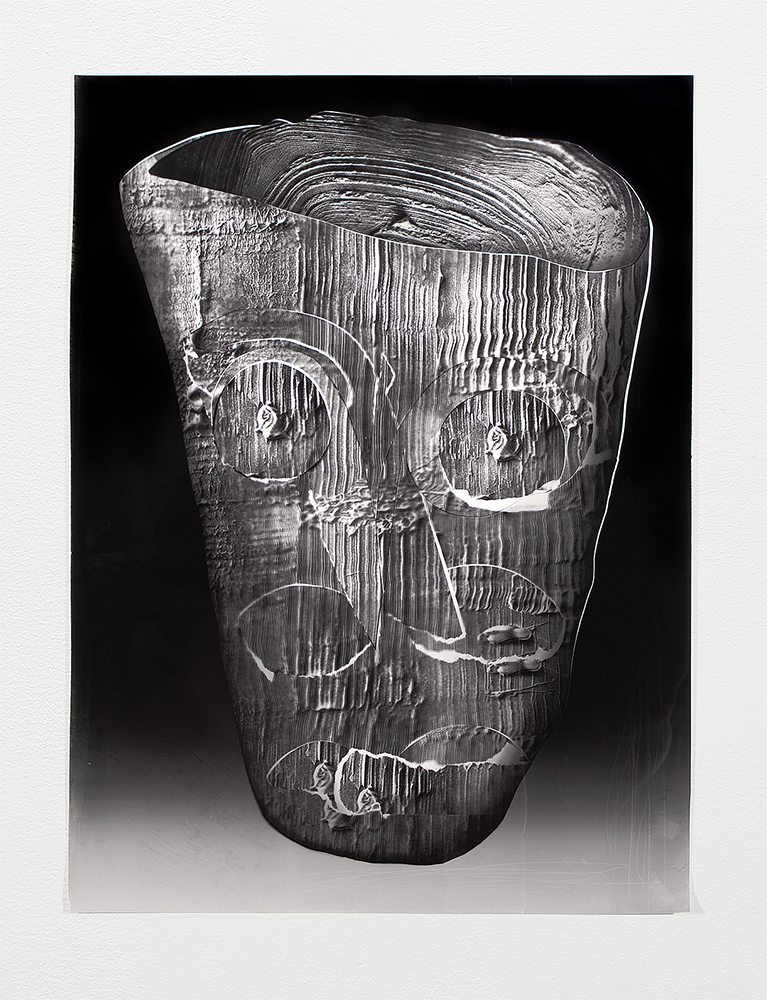

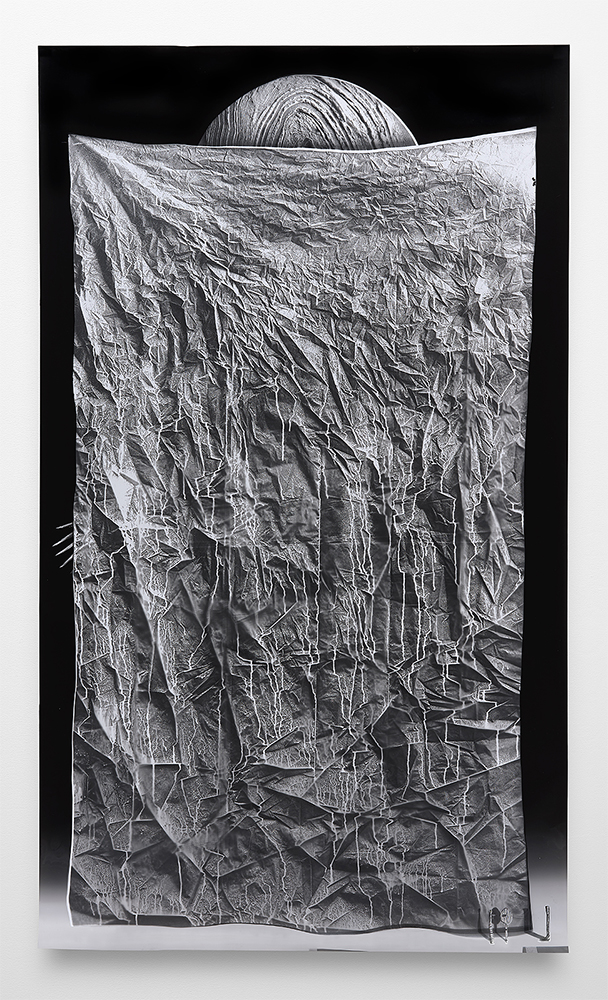

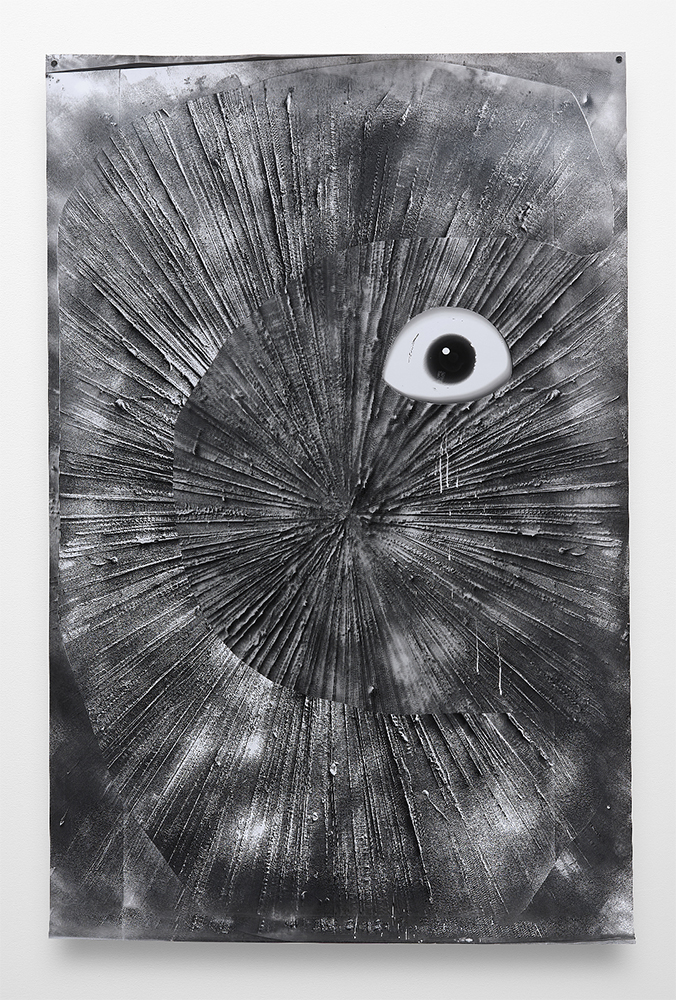

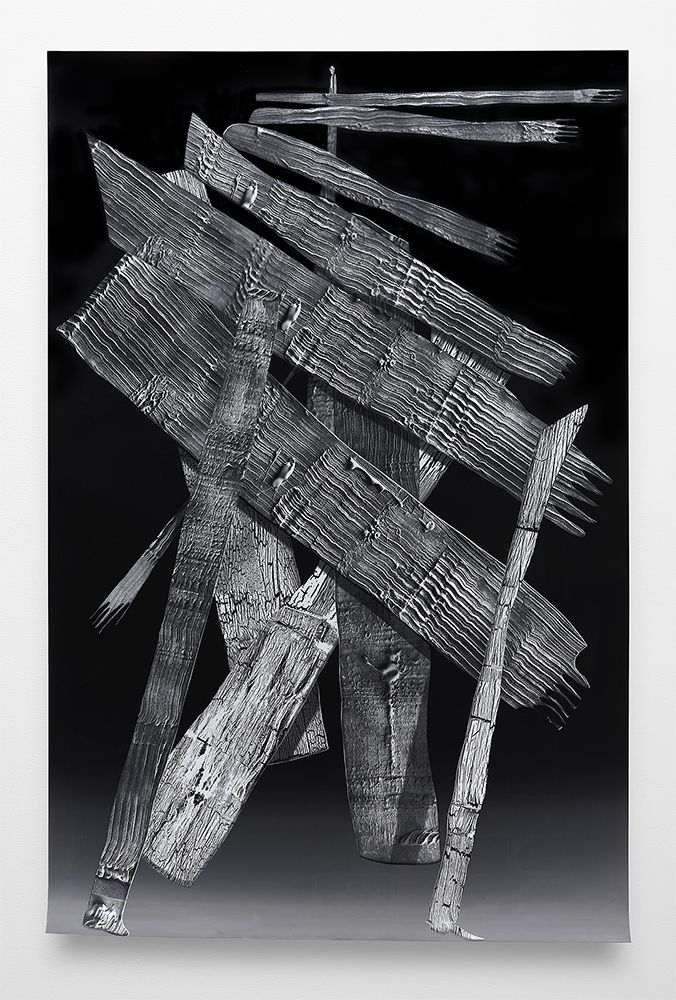

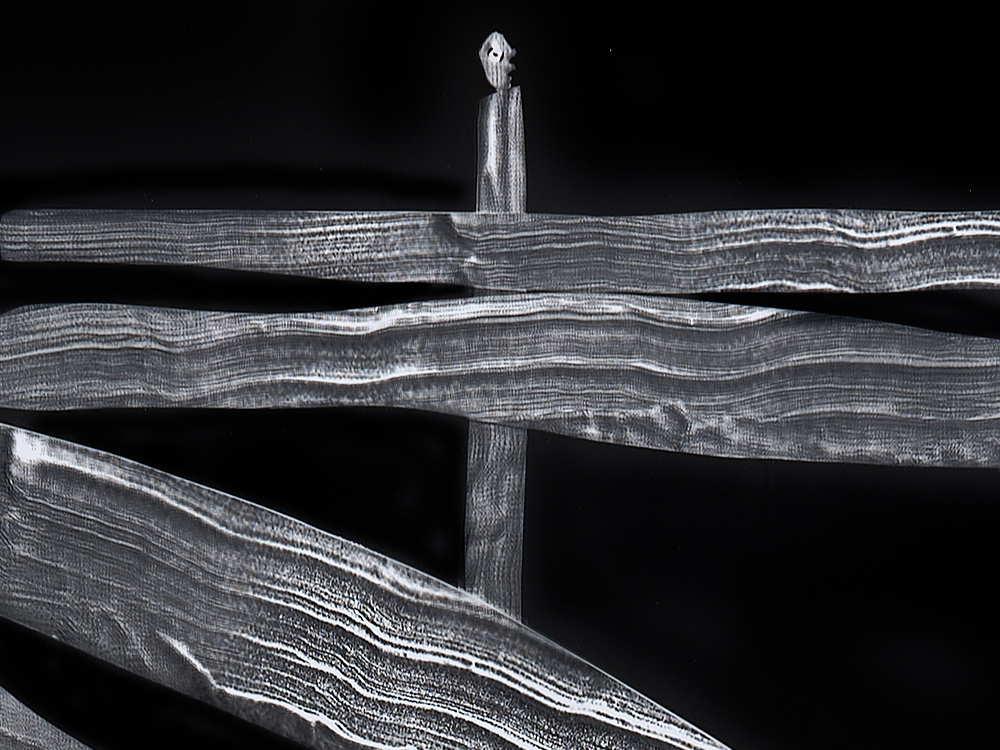

Biomorphic forms cavorting in impossible landscapes animate the horizonless spaces of Ryan Peter’s monumental photograms. Scattered rune-like elements hint at secret information or dream notations. Some of the heroic abstractions populating Peter’s images cleverly invite engagement, while others evoke trepidation through their foreboding tonality, intense texture and inscrutable arrangements. Standing before each of these prints is an opportunity for reflection.

Surreal inspiration underlies each step of the artist’s process. Images are conjured, fashioned by painting and shaping light modulating materials, and then realized in the darkroom. This composite technique warps temporal assumptions about both painting and photography. Built up, layer upon layer, Peter’s “meditations on the symbolic potential of the shadow” exude uncanny power and serve as portals to the unconscious.

L.L. The point of departure for your work is automatic drawing. Can you elaborate on what brought you to use this and other Surrealist techniques as a starting point for your work? How do you make these methods your own?

R.P. I’m interested in Surrealism, and automatism in particular, based on the artists and writers who were developing methods to generate materializations of the unconscious mind. I’m not sure I’m entirely convinced this is possible, but it felt like a useful starting point. I began by creating a version of automatic drawings, which became the foundation for these works.

In traditional automatic drawing, artists aim to bypass the conscious mind using games, prescribed structures, or limitations. For my approach, I started with an image search—usually of a biomorphic sculpture or another art object. Then, I seek out visually similar images using a variety of methods, such as the “search by image” function in search engines, repeating the process until the image has transformed significantly from the original reference. For instance, an image of Henry Moore’s Helmet Head sculpture might evolve into a still from the movie E.T. I use the final image as the basis for a series of line drawings, re-drawing the form until it morphs into something unexpected. Once a drawing surprises me, I’ll translate it into painted negatives, which appear in the final works.

In my most recent pieces, I’ve reversed the process somewhat, referencing the Surrealist technique of ‘bulletism,’ where an ink blot serves as the starting point for a drawing. For these works, I begin with abstract paintings on various plastic surfaces, which I then photograph. I draw into the photographs digitally, using selection tools to isolate forms that will ultimately shape the composition.

When I started this series, I titled it “Autograms,” combining the concepts of photograms and automatism, while also drawing from the tradition of photographic artists naming their processes—like Man Ray’s “Rayographs.” At first, I thought I’d invented the term, but I later discovered that “autogram” already has a definition: a self-descriptive sentence, such as “This sentence has five words.” I found this definition fitting for the work, as it describes a self-

L.L. Photograms upend the way we think about the relationship of light and shadow. How do you employ this feature in your work? Do you look for a new narrative?

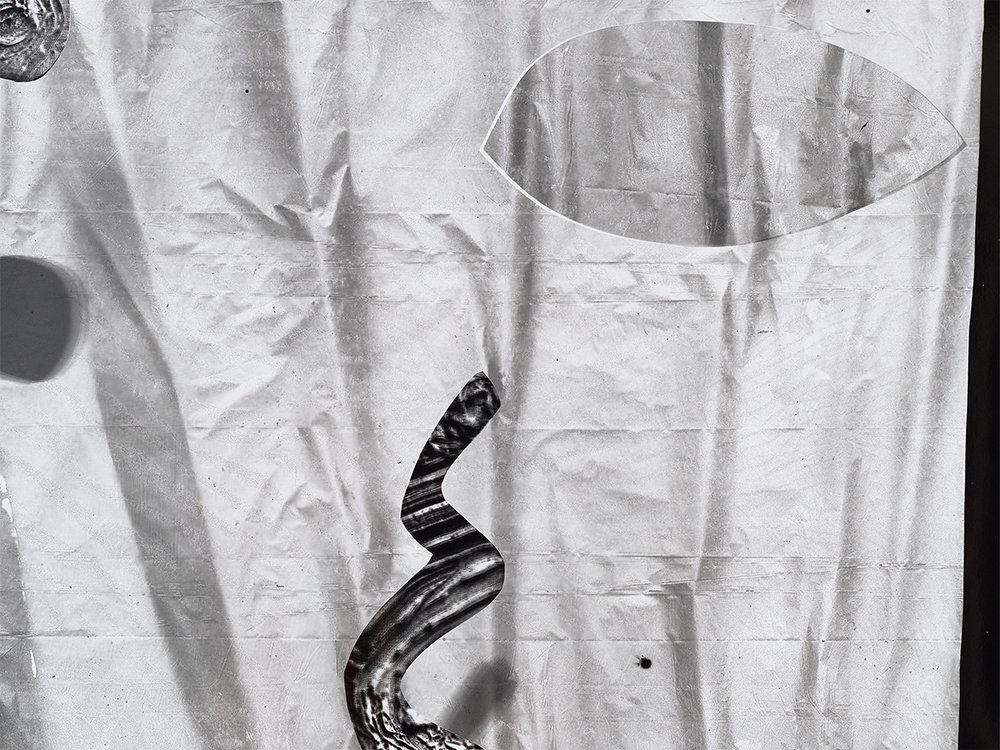

R.P. The representations of shadows in my work are created both by light passing through my painted negatives and via darkroom methods such as dodging and burning. As you noted, when making photograms, areas exposed to light darken, while covered areas remain light—an inversion of how we typically perceive shadows and highlights in both three-dimensional and illusionistic representations of space. This reversal presents a productive limitation for me as a painter, requiring me to think in reverse when creating my painted negatives.

In the darkroom, I approach the exposure process much like I would when building values in a drawing. However, instead of layering graphite to create shadows, I use light as an additive tool. I think of the shadows in these works as representations of shadows, rather than actual shadows—simulations akin to the drop shadow effect in Photoshop. These simulated shadows, however, are produced using real shadows, though in reverse.

L.L. Your process requires planning and choreographing many deliberate steps in darkness. As you execute these steps, are there opportunities for surprise and serendipity? What criteria do you use along the way to determine when your image is resolved?

R.P. The scale of the works is determined to some extent by the available media—the width of the rolls of commercially available gelatin silver photo paper—and by the scale of my body. I’m interested in their scale being more or less human-sized and relating to the viewer on that scale. Since they don’t involve an enlarger, photograms are produced at one-to-one scale, and working at this size requires large negatives—typically in the four- to six-foot range. As you mentioned, I try to plan and choreograph my exposures, but things can become rather unruly at this scale and, coupled with the limited visibility in the darkroom, exposures often don’t work out as planned. In this way, the photo paper functions as a kind of recording device, capturing all of my gestures and movements, intentional or otherwise.

Since I’m working with a developing-out process, I can’t really see the compositions while I’m producing them, so I proceed through the successive steps mostly based on my memory of the previous ones. Unlike painting and drawing, where I can see the image emerge over time, these photographic works become visible in the last few minutes of darkroom production, emerging only after processing. In this way, I see the works for the first time as the viewer might—as completed and uneditable objects. Since I can’t really change the works after development and fixing, most of the editing happens as a process of selection. My selection criteria are typically based on unexpected phenomena that emerge as a result of the process—predicated on mis-remembering, mis-registration, and neglect—surprises I become aware of after development. I might forget to expose an area or accidentally knock a negative out of registration. Often, the more failure in the process, the more surprised and, ultimately, satisfied I am with the results.

L.L. Some of your recent imagery has turned toward the depiction of a monumental, atmospheric space where the viewer might engage physically with mysterious barriers. How and why did this evolution come about? Where might it be going?

R.P. For the earlier versions of these works, I typically situated the figural elements within a setting or landscape. At that time, I was interested in constructing an illusionistic space and exploring the figure/ground relationship, which I felt complicated the indexical nature of the photogram process. As you’ve mentioned, in more recent works, a central figure—which I usually think of as a biomorphic sculptural form—inhabits an amorphous gray space, sometimes accompanied by additional satellite forms. I see this background area as a reference to the seamless or ‘infinity’ backdrops often found in studio photography. This reference to the studio backdrop is reinforced by the curtain motif that appears frequently in these works—a kind of stage within a stage. I’m also interested in this space as a nod to the amorphous mid-gray space common in digital image-making, such as the pasteboard in Photoshop or the background space in 3D modeling software.

For me, these blank spaces highlight the paper’s inherent qualities—such as the machine-produced surface uniformity, subtle exposure variations, and traces of chemical processing—and suggest the minimal elements needed to evoke spatial depth, llikethe suggestion of a horizontal line or drop shadows. I’m not entirely sure at the moment how this compositional device will evolve in future works, but it is something I plan to continue exploring—perhaps by bringing it more to the foreground or by finding ways to further complicate the figure/ground relationship.

Artist Biography

Ryan Peter is an artist working at the intersection of painting, drawing, and photography. His work has been featured in exhibitions at museums and galleries in the US and Canada, including the Vancouver Art Gallery, Polygon Gallery in North Vancouver, Susan Hobbs in Toronto, Platform Centre for Photographic and Digital Arts in Winnipeg, and the Walter + McBean Galleries in San Francisco. In 2024, he had a solo exhibition at the Green Gallery in Milwaukee titled It only works if everyone believes it does. Peter has received project grants from the Canada Council for the Arts and the British Columbia Arts Council. He is currently an Instructor at the Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design and a Lecturer in the Department of Painting and Drawing at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Website: www.ryanpeter.com

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Bill Armstrong: All A Blur: Photographs from the Infinity SeriesNovember 17th, 2025

-

Robert Rauschenberg at Gemini G.E.LOctober 18th, 2025

-

Erin Shirreff: Permanent DraftsAugust 24th, 2025

-

Shelagh Howard: The Secret KeepersJuly 7th, 2025

-

Michelle Leftheris: Time, Nature & TechnologyJune 11th, 2025