Anne Eder: The Seer

I first met Anne Eder when taking her Plant-Based Photography workshop. I was instantly intrigued by her work, which is in deep conversation with the natural world. Once I entered Anne’s virtual classroom, I found out what an incredible educator she was, too. Since then, I’ve had the great fortune of working as the facilitator (aka teaching assistant) for a few of her workshops and continue to learn from her wealth of knowledge. Whether she’s bringing us into her garden to share which leaves are best to choose for Chlorophyll printing, or taking us through the lumen process, she is endlessly inspiring. Whenever I’m talking about Anne to others, I will often call her the “Queen of Alternative Processes” and I believe she has rightfully earned this title!

We had this conversation over email, where we discussed fairy tales as inspiration, the addictive quality of lumens, ephemerality of art, and a gallery show that smelled like the woods.

Anne Eder is an interdisciplinary artist and educator. She is respected and sought after internationally to exhibit, teach workshops, and participate on panels. She is currently a lecturer in the Lewis Center for the Arts, Princeton University, instructor in the Harvard Ceramics Program, Harvard University, faculty at Penumbra Foundation NYC, Santa Fe Workshops, and the Griffin Museum of Photography. She teaches workshops at venues across the country and, via online learning, all over the world. Much of her work is experimental and research based, combining historic processes, science, and contemporary conceptual thinking. She is well known for her classes in sustainable photographic practice and processes, and for innovative discoveries regarding both photographic chemistry and integrating media. Throughout her career she has been an advocate for increased access to the arts, and the creation of public art is a dedicated part of her practice. She lives in New England with her fabulous chihuahua, The Brain.

You can find her on Instagram @darcflower.

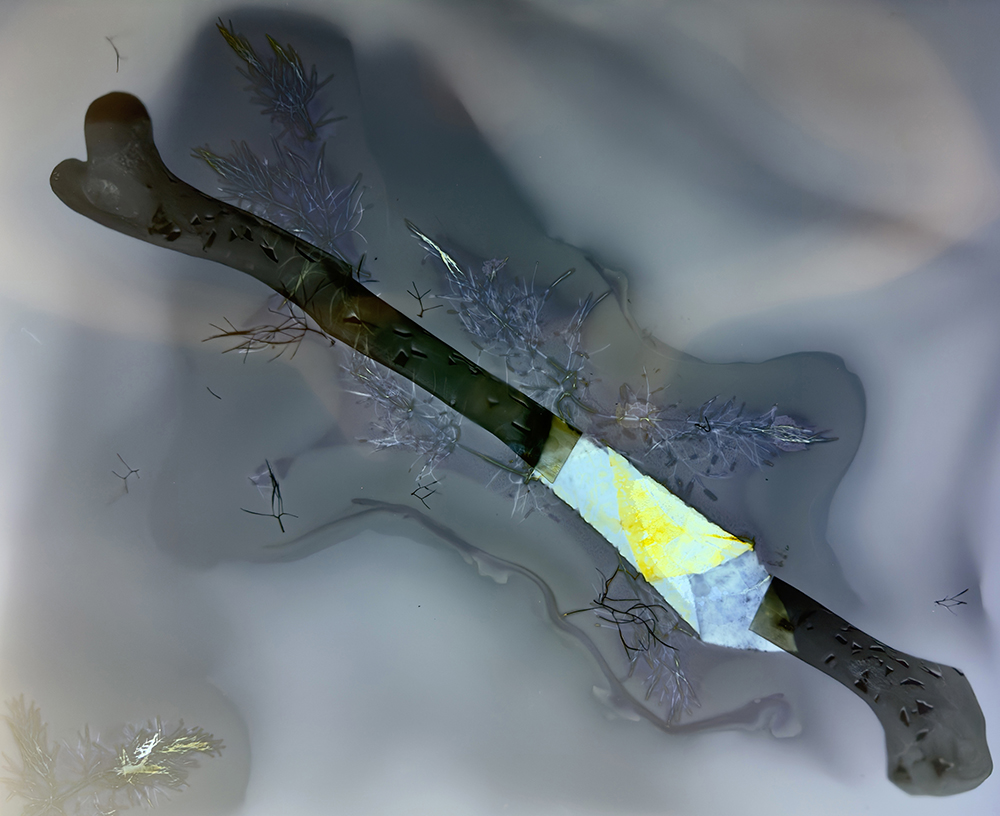

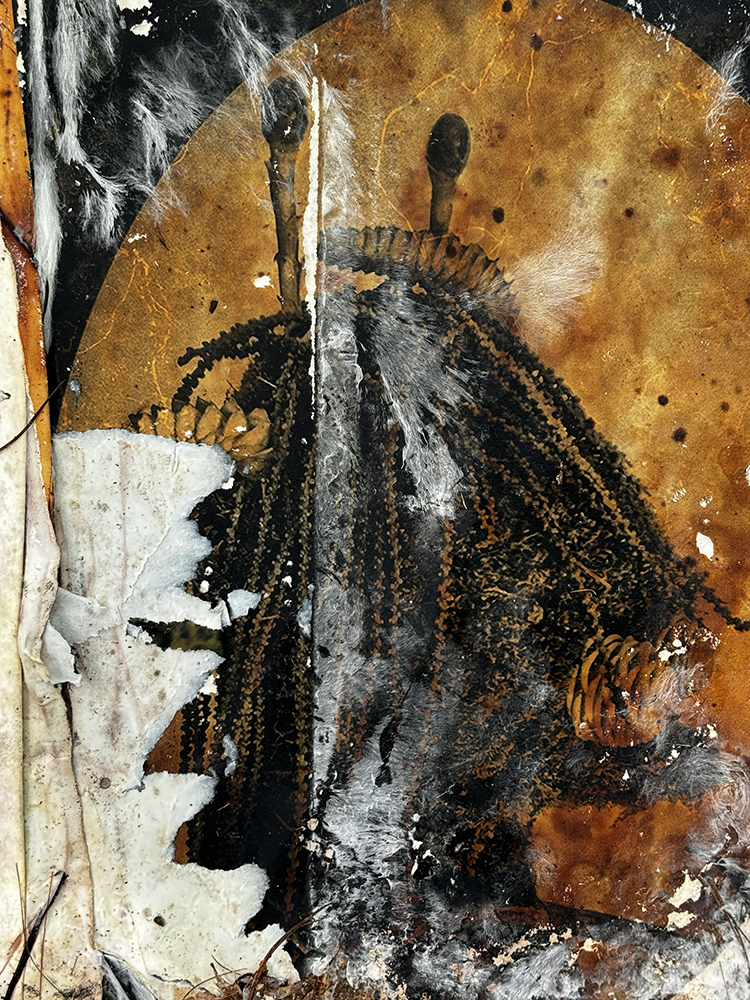

As an interdisciplinary artist, educator, and researcher, I often describe my work as taking place where the natural world meets the narrative impulse. I am interested in the core role nature plays in the formation of our mythologies, folklore, and fairytales, and in the way specific geographies give rise to discrete stories, folding history and memory into place. In nature, one thing often suggests another—branches are tentacles, dendrites, lightning.

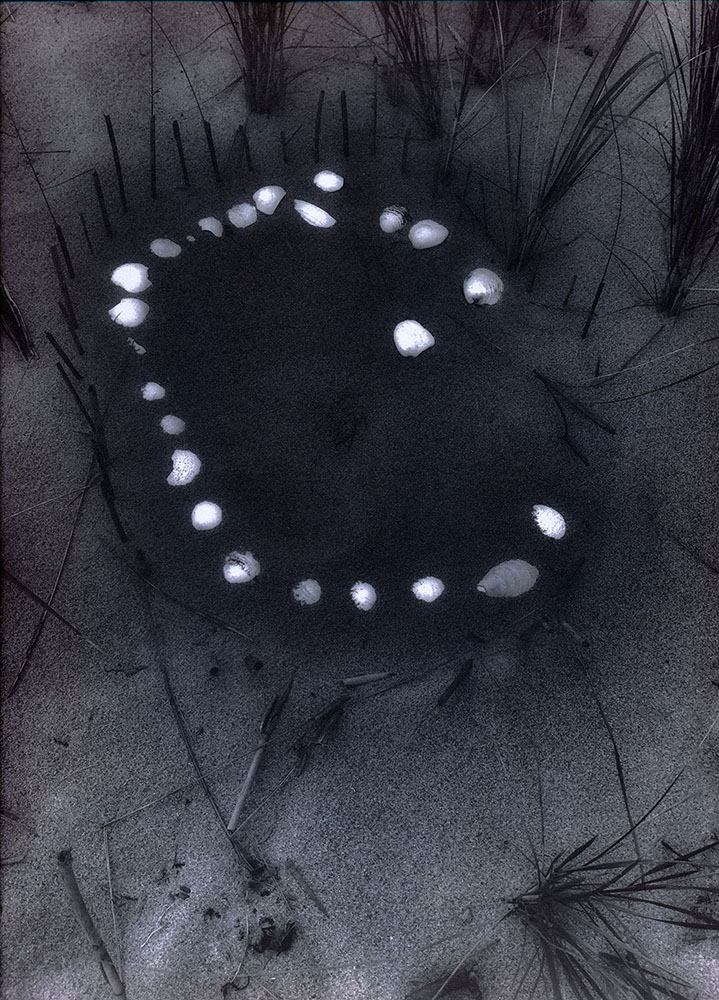

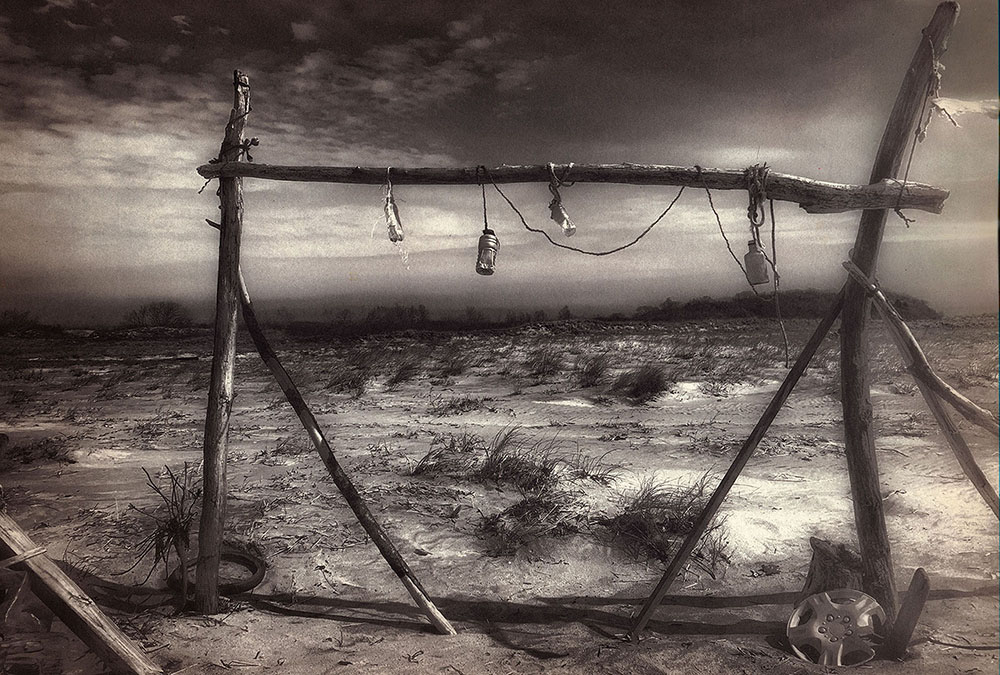

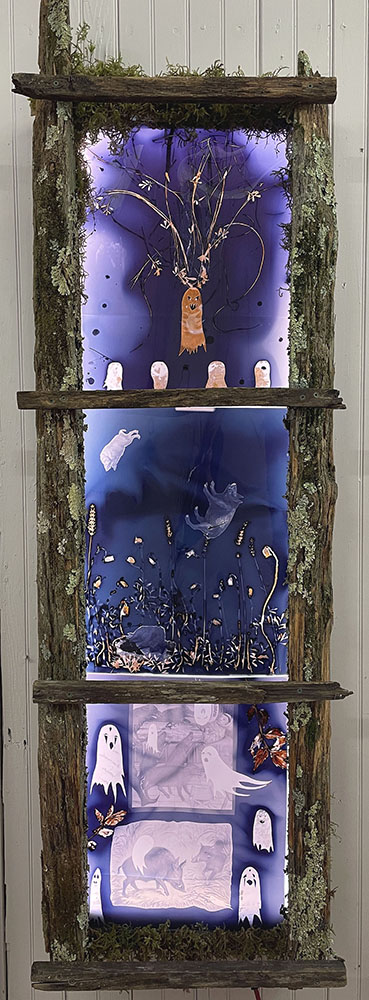

A line of rock becomes a spine, stegosaurus plates, armor. These connections, combinations of pattern recognition and embedded ancient narratives, are the raw constituents of my practice. I create sculptures from organic materials, otherworldly creatures that evoke mythical dimensions, and document them through photography from installation to their decomposition back to the earth.

Stories fire our imagination, give us hope, and support our ability to problem solve. By employing fictional beings like monsters and ghosts, and semiotically charged objects such as teeth, bones, or cocoons, I provide an easy point of access and tap into the language of internalized stories. – Anne Eder

Montserrat Andrée Carty: Can you share a bit about your background––how did you first get into photography, how your practice has evolved over the years, and what most excites you today?

Anne Eder: My background. Well, I was always a sort of square peg in a world of round holes. I’m a messy artist, and my practice includes sculpture, installation work, and storytelling in addition to photography. I received my first camera (a Kodak Brownie!) as a hand-me-down from a relative when I was eight years old, and immediately began to use it to document all kinds of daily minutia. So, I was shooting medium format film as a kid and developing my own from the time I was about 18. It was both how I saw and how I mediated the world around me, which was often a very unsafe place for me as a child.

I’ve actually never referred to myself as a photographer, and even my baby artist’s first business cards read “Photographic Illustration.” My major influences are illustrators, not photographers. Artists like Chris Van Allsburg, Shaun Tan, comic book artists, old children’s book illustrators like Feodor Rojankovsky, and even religious iconography. That said, my master’s degree is in Photography and Integrated Media, with a focus on the handmade photographic object and ethics related to the medium.

Like plenty of young photographer’s, I began in a fairly straightforward documentary manner. I only ever wanted to shoot black and white. I’m a control freak about color and prefer adding it post processing and quite selectively. I was self-taught, though I had mentors, and I apprenticed myself to an AP photographer early on who taught me a lot about working in the darkroom. I also worked in an analog lab printing and retouching for other photographers which is a good way to hone your skills. I quickly moved from that to combining various methods with photography such as hand coloring, double exposure and collage, transferring images onto fabric, and playing with Xerox and Canon copiers. I made wall hangings and art to wear, xerographic prints, and silver gelatin images.

As a single mom for most of my adult life I photographed my children, of course, and as many neophyte artists do, I also used self-portraiture in feminist gestures and to advance narratives. When I was free to go to graduate school, I entered a period of deep reflection on the ethical quandaries that are inherent to photography and moved away from street and intimate portraiture. I was drawn to the history of photography and its materiality, and I began working collaboratively with my subjects. I eventually just started building everything that went into my frame. That is what my practice is like today—making several hundred porcelain teeth, covering bones in soft willow catkins or crushed velvet flocking, draping ten-foot armatures in 120 cubic feet of moss.

I reached a point where I no longer wanted to contribute to the glut of commodities or to focus on art as a marketplace. When the work becomes a commodity, it changes what you will create. You may have an idea and then think, that will never sell, and then you don’t make that thing, it never exists. Now I am more inclined to think first of all, sustainably, and second, to offer something tactile and experiential. Most of my sculptural work and some of my images are designed to decompose and return to the earth. I accept the ephemerality of art, of our bodies, of this world.

What excites me? Literally everything haha! I am immersed in the science and chemistry of photography, in the alchemy of it all, doing lots of research, and have so many stories left to tell. I am excited about building a practice around reciprocity—not in the photographic sense of proportions and math, but in relationship to the natural world, challenging myself to give back by coming up with less toxic solutions and methods and then sharing those in my role as an educator so that my students become more engaged with the natural world and invested in its protection. At the core of my practice are gifts from the earth, from the plants that I use to make an image, a developer, or a monster, to the metal salts and minerals that are part of all photographic practices. This requires that I reciprocate by taking care of the natural world and disseminating knowledge through my classes and photographic panels.

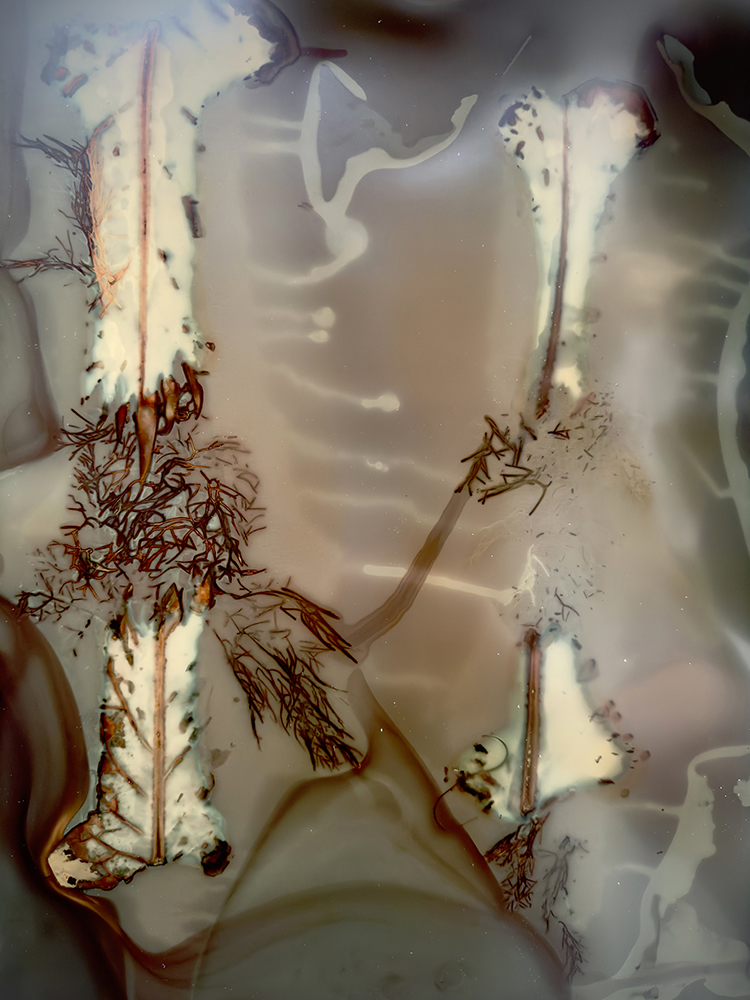

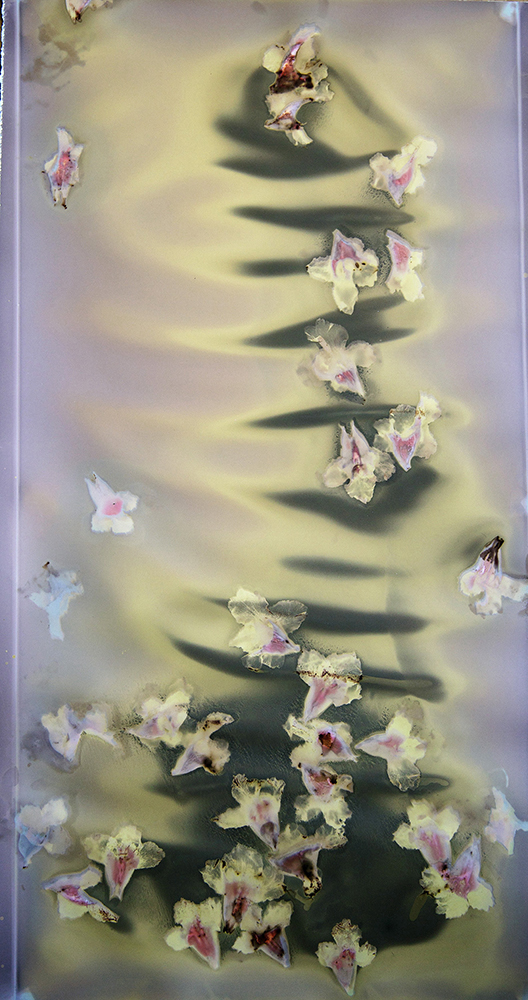

MAC: In your various bodies of work you use multiple alternative (cameraless) processes including lumens, anthotypes and phytograms. How do you choose which to use when?

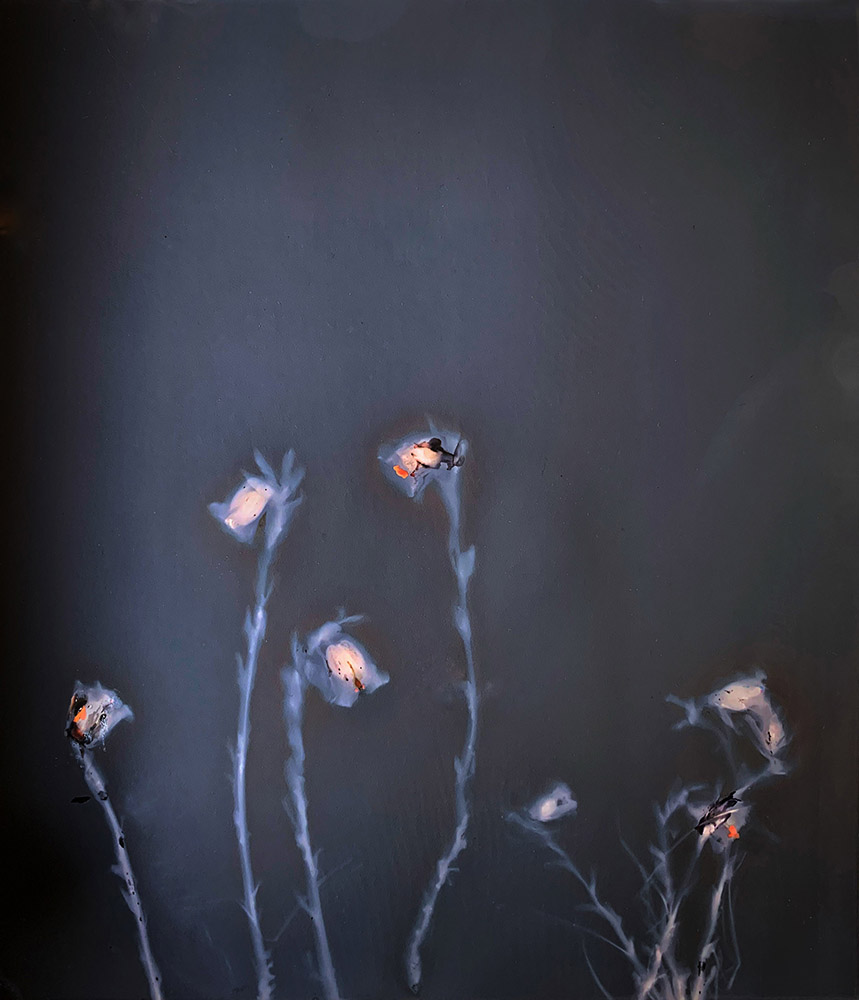

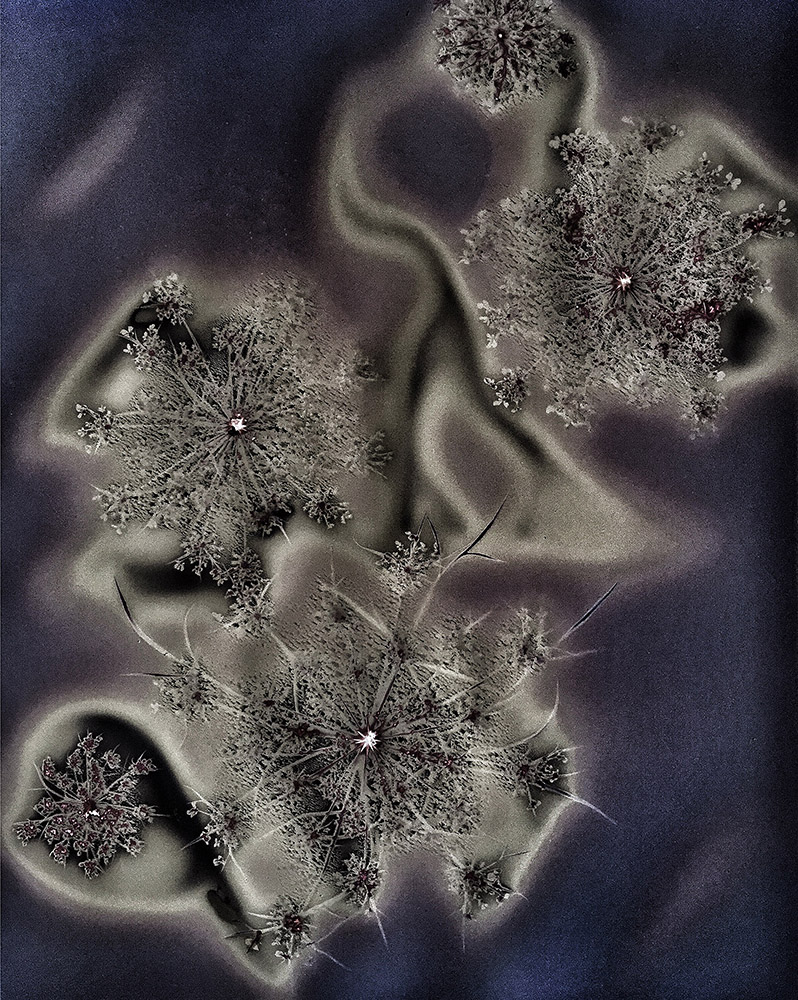

AE: Content to process relationship is the crux of it all, isn’t it? It’s what lifts process up to the level of artmaking. I’ve been thinking for so many years about craftsmanship and materiality in photography, about photographs as objects, (if you have never read it, I highly recommend Photographs, Objects, Histories by Elizabeth Edwards and Janice Hart) and I am always seeking the proper syntax and presentation for an image. Sometimes that takes time, detours down wrong paths, testing hypotheses, failing. It may even take years to find the correct process for a specific body of work. For example, I build these large sculptures of what you might call monsters, and over time I have printed them in various ways, from gum bichromate to platinum. I finally hit on documenting them in plant emulsions using the flora from where they are sited and ended up with the series of skunk cabbage anthotypes that was recently shown at Halide Project in Philadelphia and featured on Lensculture. They were exhibited unframed so that the gallery smelled like the woods.

Another series with an intersection of process and content that I am satisfied with are the images of the land, ocean, and salt pannes in Mysteries of Plum Island. Because the island is at risk due to climate change, I wanted a direct connection to place as a way of preserving it in some real and tactile way. That led me to soaking the paper in seawater from the site in order to make salted paper prints using silver nitrate, one of the earliest forms of photography practiced by Henry Fox Talbot in the early nineteenth century. It met my requirement of relating to the site in a physical way, but also on another level by introducing an element of the primordial, the inexorable. The sea as ancient and salty, the prints made using a salty and simple method.

MAC: Can you share a bit about the ways fairytale and mythology influence your work?

AE: I think that if you look at the prevalence of fictional forms in nearly every culture, it is hard not to make an argument for it amounting to some form of evolutionary survival mechanism. The best of my childhood memories involves being in the woods of West Virginia; my brother and I, close in age, left to our own devices. The worst of my memories you don’t want to hear about. My brother and I would fish, catch insects to examine them, dig clay soil to make artifacts, collect rocks, and tell each other stories about monsters and bears. Mostly we hiked and listened and observed. Those woods were a safe haven, but also called to mind the Germanic woods of the brothers Grimm or the French forests in Perrault’s Red Riding Hood. I always had my head in a book and lived for the bookmobile to come, leaving each time with a tall stack of stories, from Beowulf to the Hobbit, and fairy tales of all stripes. I carried that interest with me as I grew up, and immersed myself in Amos Tutuola’s, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, The Swamp Thing Saga, and the work of the Hernandez brothers in comics like Love and Rockets, which drew on Hispanic culture. As a grad student, I was incredibly fortunate to have Maria Tatar as a mentor, who has written many scholarly books on fairytales. I am interested in how geography and geology give rise to discrete myths and folklore, in the huge role of the natural world in forming our core mythologies, fables, and even religions. I use fairytale structures as a point of entry. The familiarity of the structure allows viewers to move into the work with ease. I use certain semiotic objects over and over—teeth and bones, flowers, ghosts, monsters. Monsters take on a lot of cultural work. They can represent otherness, fear of the unknown, our own binary nature. They exist in every culture, everywhere in the world. We may see the monstrous parts of ourselves reflected back at us, or perhaps there are a few like me, who see them as protectors or even avatars.

MAC: It’s interesting to think how fairy tales and myths can be so dark and yet, your lumen work is literally shaped by light, using sunlight to expose the images.

AE: That is literally a core part of my work, and I am so glad to hear you say that! Without the light, my monsters, ghosts, and shadows would not exist. In the end, I think myths and fairytales give us hope that difficulties can be overcome. I believe that imagination is a sort of muscle that we need to exercise, and one of the ways we do that is through fiction. This helps us with pragmatic things like problem solving.

MAC: I remember in class during lumen week you’d say lumens are the most addictive process! Can you talk a bit about what draws you to lumens as an alt. process in particular? And, do you generally play with materials you’re drawn to and see what comes out, or do you begin with a clear idea of how you’d like the lumen to come out?

AE: The thing that I love about lumen prints and phytograms is the way they transform the material. On the one hand, I would argue that they are even more indexical than a photograph made with a camera, and on the other, the resulting image can be quite unrecognizable. I often refer to black and white silver gelatin paper as a magic canvas because it truly is! It is sensitive to light, humidity, temperature, and chemistry. It is almost an active participant and collaborator. Although I would say that I am a process driven artist, experimentation is one phase and art making is another. I build up data by experimenting and that allows me to control the image making to create a series.

MAC: Do you preserve your images, whether by photographing or fixing them, or do you feel leaning into the ephemeral nature of this work is important? During an exhibit, do you let the work change throughout the weeks, months it’s up so that every viewer will see the images uniquely at a particular moment in time?

AE: I have handled the ephemerality of some of the processes I use in a number of ways. For exhibitions, I have chosen to show work in its fugitive state as well as documentation printed using methods considered quite archival, such as platinum and palladium. If we are being honest, it’s all ephemeral. Kate Palmer Alber’s book, The Night Albums, is beautiful and articulate writing on photographic ephemerality. Any photograph is only as permanent as the substrate it is printed on, how that is stored, if it manages to escape being in a fire or a flood. In a way, it heightens the viewing experience when a print is shown in a fugitive state, knowing that it has to be viewed now, not later, and that as a viewer we are complicit in its destruction.

MAC: Let’s talk about your wonderful body of work “Mysteries of Plum Island.” Of the project, you write:

It is a visual record of a place that will cease to exist. It consists of photographs of select beach detritus and the landscape printed as palladium or salted paper prints made using seawater, archival inkjet prints, video clips, and an organized collection of found objects.

I am so curious to hear more about the process behind these images, and anything you learned in the process!

AE: Thank you! Plum Island is a unique place. It is a seven-mile-long barrier reef and wildlife refuge dangling off the northeastern corner of Massachusetts about 50 miles north of Boston, currently at risk due to climate change. It is closed to the public from April until mid-August every year for plovers nesting and raising their chicks, and I am convinced that these long absences of human presence have created a sort of dimensional rift, a soft spot between dimensions. You can sense the parallel universes of reality and old magic. Most of my work there is an effort to recreate how it feels to be present on the island, to hint at its mysteries, but I am not interested in literal documentation. Sometimes a fictional/factual approach comes closer to replicating a sense of place than a more straightforward documentary. On the day after I was first there, a woman’s body washed up on the shore where my footprints may have still marked the sand, forever coloring my perceptions.

There is a lot of garnet in the sand, and sometimes the whole beach is purple—it looks crazy. And I have always had a fondness for salt marshes. They are lonely places, but absolutely teeming with life forms. Beautiful in a desolate way.

MAC: Lastly, in addition to being an incredible artist, you are such a wonderful art instructor. You teach all kinds of processes to students of all ages and backgrounds. You have influenced so many artists and I wondered if there was a mentor, teacher or class that had a strong impact on you when you were in school?

AE: I enjoy teaching very much, and I always learn from my students. During the pandemic and in this divided political environment, I really questioned the value of art making, but education continued to feel important and worthwhile.

Growing up, I wasn’t from a wealthy or educated family, but I did have some teachers along the way that introduced me to many things, and who fostered my curiosity and nurtured my intelligence. In grade school, I had a science teacher who gave up personal time to encourage a few of us to come outside of class and peer through microscopes at paramecium or engage in chemistry experiments. In high school, my art teacher was a nun who was probably one of the most passionate artists and teachers I have ever known. She could talk about mixing a gray paint that made it sound almost ecstatic. Given her vows of poverty, it was never about commercial success for her, only about love, and I think I internalized this more than I realized at the time. My limited access as a child made me an adult who prioritizes it. The creation of public and affordable art is a dedicated part of my practice.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Carolina Baldomá: An Elemental PracticeJanuary 5th, 2026

-

Time Travelers: Photographs from the Gayle Greenhill Collection at MOMADecember 28th, 2025

-

Suzette Dushi: Presences UnseenDecember 27th, 2025

-

Ragne Kristine Sigmond: Portraits of Painterly LightDecember 2nd, 2025