James Nakagawa: American Truths

In the spring of 2017, I walked into Professor James Nakagawa‘s office at Indiana University, Bloomington, shortly after accepting my offer to join the Master of Fine Arts program. Surrounded by a vast array of his works and an impressive archive, I felt both awe and a bit overwhelmed during our initial meeting. We talked for a bit, and James was curious about my other graduate school options. Then, he threw me a curveball: “You’ve received an offer to study here, so what can you offer us?” Not expecting this kind of question, I quickly replied, “the next three most experimental years of my life.” To this, James seemed to ponder for a moment before responding, “…hmm, good answer!” Reflecting on that initial first meeting and the subsequent years under his mentorship, I am excited to share this interview I conducted with James Nakagawa on his latest trilogy American Truths.

Osamu James Nakagawa was born in New York City in 1962 and raised in Tokyo. At 15, he moved back to the United States, settling in Houston, Texas. He earned a Bachelor of Arts from the University of St. Thomas Houston in 1986, followed by a Master of Fine Arts from the University of Houston in 1993. Professor Nakagawa currently holds the position of Ruth N. Halls Distinguished Professor of Photography at Indiana University in Bloomington. His accolades include the 2009 Guggenheim Fellowship, the 2010 Higashikawa New Photographer of the Year, and the 2015 Sagamihara Photographer of the Year in Japan. Nakagawa’s work has been showcased internationally, with notable solo exhibitions such as Witness Trees at PGI, Tokyo, in 2023; GAMA Caves at Sepia EYE, New York, in 2014; and the OKINAWA TRILOGY at Kyoto University of the Arts in 2013. His work is included in numerous public collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, George Eastman Museum, Tokyo Photographic Arts Museum, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and others.

James Nakagawa on the trilogy American Truths

Two months after Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, forcibly incarcerating approximately 125,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans, mainly in camps in the arid American West, many of which were constructed on Native American land. Many families suffered the dual trauma of losing their land, homes, and businesses while being isolated in the camps’ harsh desolate

environments at the hands of their own government.

The turmoil of the pandemic, the killing of George Floyd, and the increased anti-Asian hate crimes during the end of Trump’s first presidency were a painful reminder to me of America’s deeply ingrained systemic racism. As the nation faces the prospect of another Trump presidency—one already threatening mass deportations from day one—I feel a chilling sense that history is repeating itself. I feel a sense of urgency to highlight the Japanese American incarceration experience because the injustices of the past are still shaping the present, and we cannot afford to look away.

This led me to wonder about the experiences of Japanese Americans whose ancestors immigrated before World War II. Unlike my family, who came to the US during the post-war economic boom, these older generations of immigrants and their descendants seemed guarded as if they were carrying a burden of an American experience that was too much to speak of. As a Japanese American living in the United States for almost 50 years, I still feel like an outsider in both cultures. I am a stranger in all the places my family could call “home.” When I turned 60, I had to part with my parents’ home in Japan. Together, these things forced a personal reckoning: I was symbolically severing my connection to the place my family has always called home while questioning, yet again, my value in the eyes of my adopted country.

In February 2022, on the 80th anniversary of Executive Order 9066, I began what would become a 24,888-mile pilgrimage to visit the sites of every incarceration camp established after the 1942 Executive Order. To visit the sites of these camps exposes an indescribable reality. Upon my first arrival, I was taken aback by the vastness of nothingness and the geographic isolation of these places. When I arrived, I closed my eyes and imagined the thousands of people confined to this barren nothingness. My challenge was how to visualize this embedded history.

From this pilgrimage, I have worked towards creating three different bodies of work–IF • NOW, Trace, and Witness Trees–that became a trilogy, the American Truths. I hope these bodies of work question what “truths” are being told.

SC: James, thank you first and foremost for collaborating with Lenscratch on this interview. It’s great to chat with you after being away from campus so long!

JN: Thank you so much for having me, Seth! It’s been a real pleasure catching up and seeing how much you’ve grown since your time at Indiana University. It’s amazing considering you graduated during the pandemic and was unable to have an in-person thesis exhibition. Despite the challenges of that time, I was really impressed by how determined you were to push yourself to construct a strong, inspiring body of work. You stayed committed to your art without dwelling on the circumstances. I admired how you poured your heart into your thesis project, even without a physical exhibition. You’ve really inspired me, and you’ve contributed so much to your peers as well.

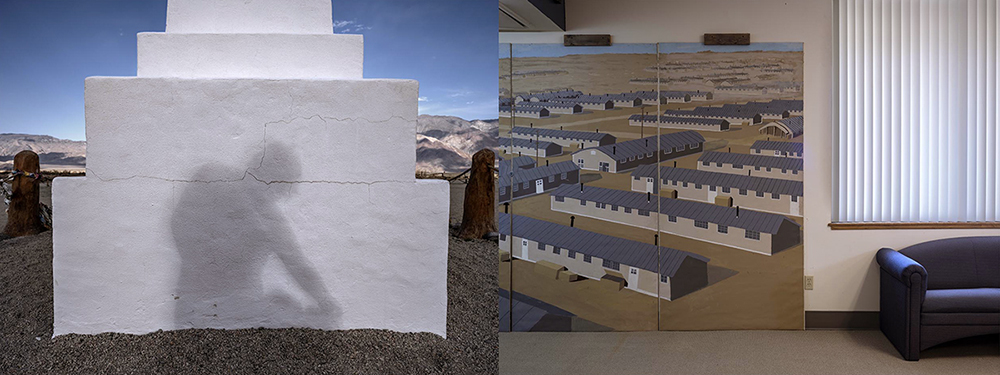

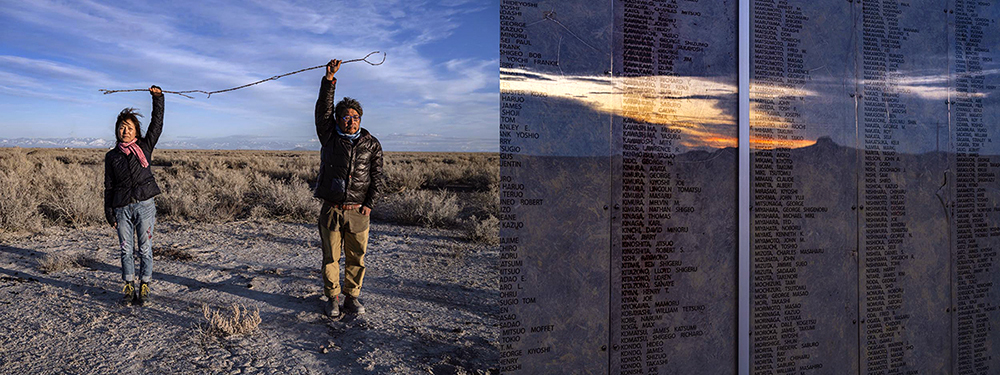

SC: So, I thought it would be great to start with the series IF • NOW. When you look at the self- portraits paired with the camp landscapes that you documented, what stood out to you the most about what they say to the viewers, or what the pairings of the portraits with the landscape say to the viewers?

JN: Well, initially I didn’t plan on creating diptychs. My first visit to a campsite was to a desolate landscape, which was quite striking, especially under different lighting conditions. Responding to the shifting shadows and the stark terrain, I thought incorporating human elements might add depth. The idea came when I asked my wife to stand within a tree’s shadow, but it soon became clear that I needed to be the subject to convey the emotions and history of the place.

Taking these self-portraits at various historical sites became a rule during my pilgrimage, challenging myself to explore vulnerability and self-consciousness. Each image not only captures me in these significant landscapes but also questions the viewer about the space and its history. These diptychs do more than just juxtapose two images; they connect personal and collective histories, urging the viewer to question beyond what is visible. This approach has evolved into a broader exploration of how landscapes and personal presence interact, enriching the narrative of each site I photograph.

SC: Objects such as barbed wire reappear throughout the series. Could you share what prompted you to include these and what they represent to you?

JN: During my first pilgrimage, I was confronted with a vast, desolate landscape that was visually not very exciting to photograph. This prompted me to explore self-portraiture as a means of engagement, beginning at the Rohwer incarceration camp in Arkansas. That photograph serves as proof of my experience at the site, as I immersed myself in the light, shadow, air, dust, wind, and scents of the former incarceration camp. By the time I undertook my second journey, I approached the experience with a clear sense of purpose, carefully selecting my attire and props to reflect my dual identity as both Japanese and American.

It was during my second pilgrimage that I began to incorporate objects like barbed wire, which resonated deeply with my previous work concerning the U.S. military’s presence in Okinawa. Imagery such as the one with barbed wire stretched between my wife and me against a barren backdrop, serve to emphasize themes of resilience and defiance. These elements are crucial to reflecting the historical experiences of Japanese Americans during their incarceration. Through IF ・ NOW, I seek to engage with my Japanese American identity and historical memory, blending powerful symbols into landscapes that carry rich personal and collective narratives.

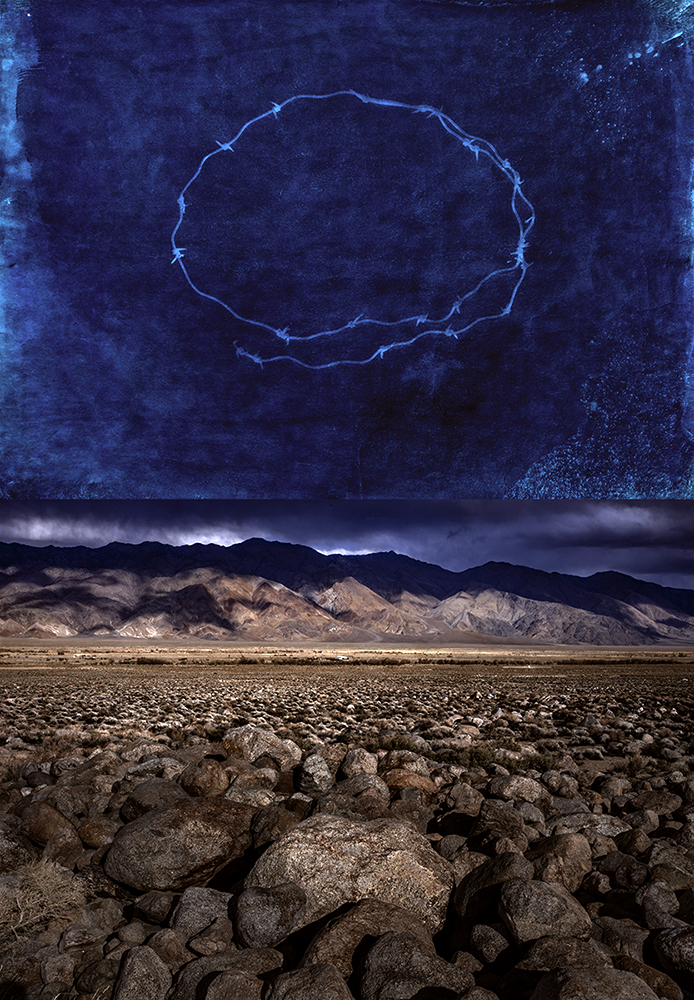

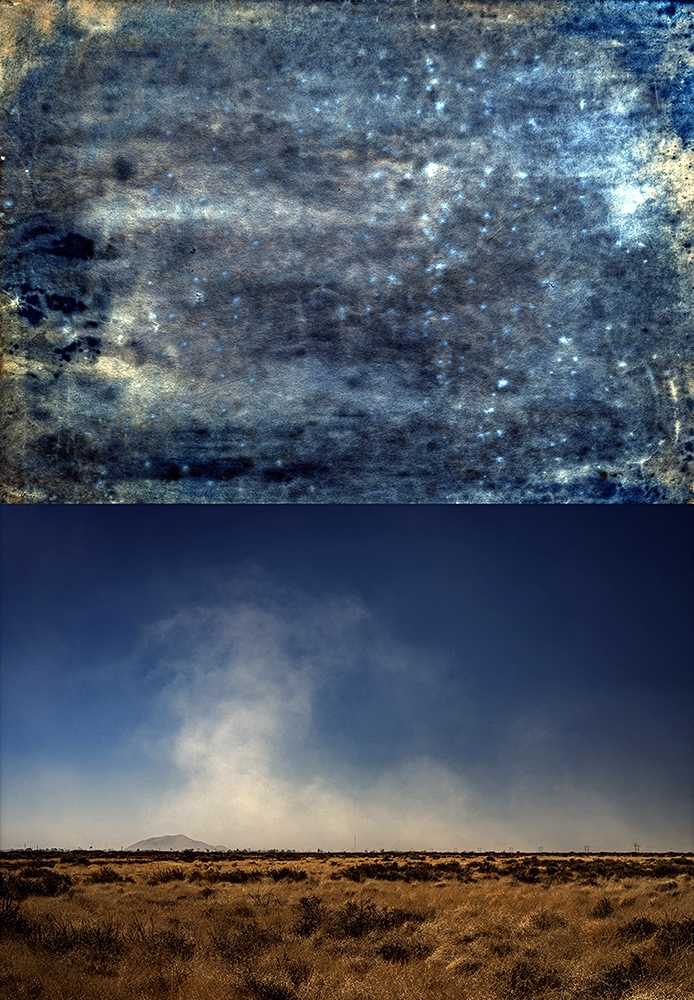

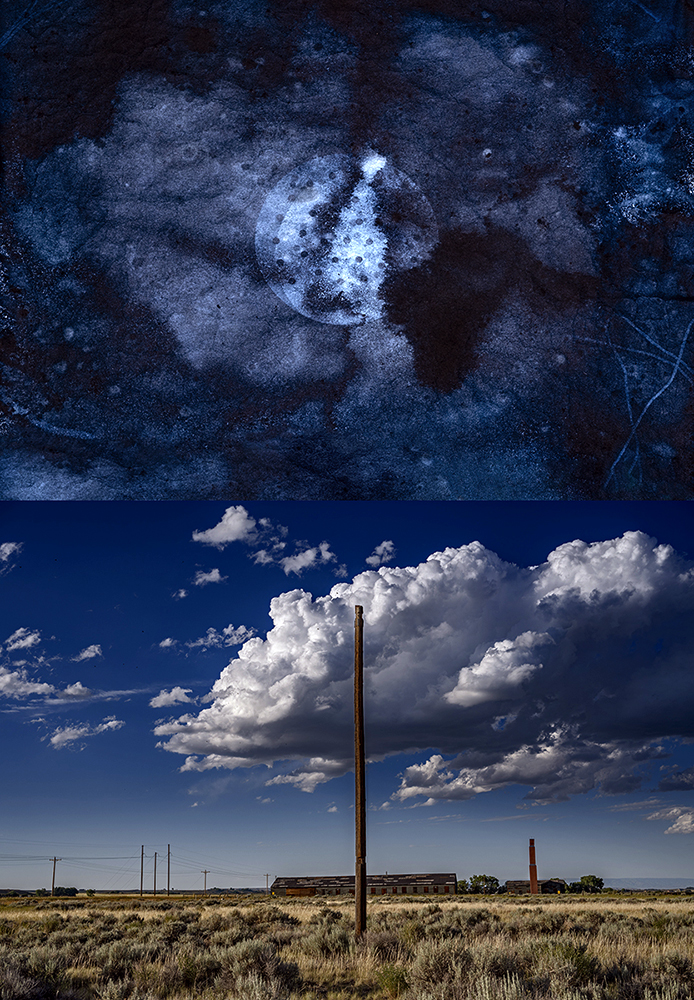

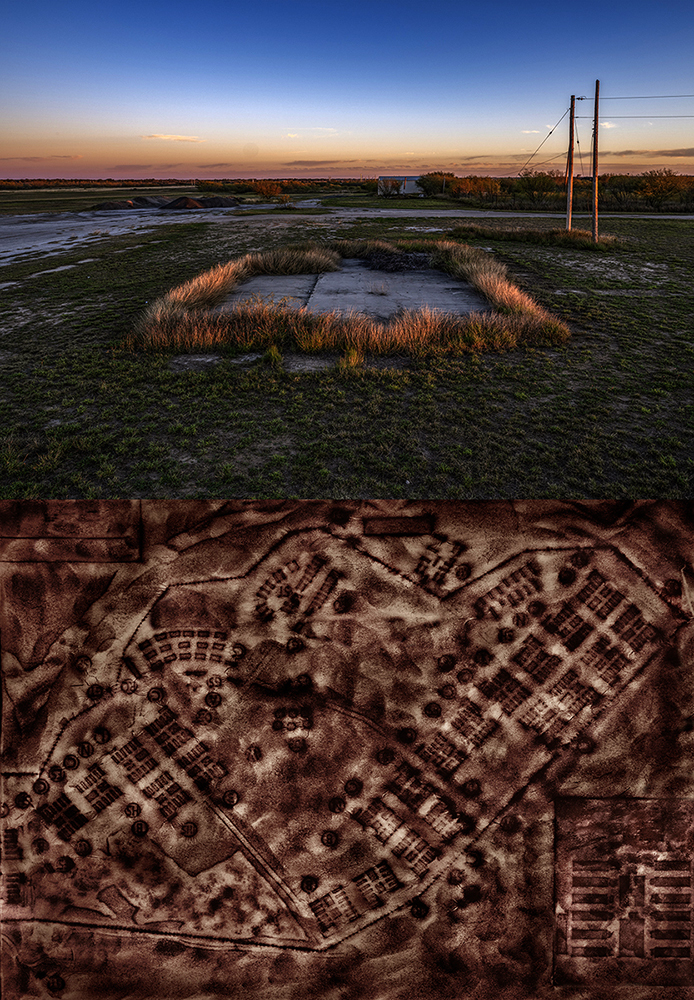

SC: Thank you for those insights into IF ・ NOW, James. Moving on to Trace, the next part of your trilogy, what inspired you to use cyanotype photograms in conjunction with your landscape images? Were there any surprises about the process or the subject matter that emerged as you began assembling the series

JN: Much like my pilgrimage for IF-NOW, I had no specific plan for the cyanotypes. My previous work in Okinawa involved creating cyanotypes directly on the American military fences, culminating in a large installation for the Hamberg Photography Triennial curated by Koyo Kouoh in 2002. This project highlighted the immediacy and physical trace that cyanotype photograms can capture—direct impressions of objects on paper, rendered life-size in the installation. This process has a tactile immediacy; I came to realize it’s like tracing the object’s history directly for the viewer. Combining these elements took about a year of experimentation in the studio. I ended up digitized cyanotypes to create brown-toned prints, combining them with photographs from the sites to visualize the sky (cyan) and the ground (brown), honoring the landscapes as sacred representations of heaven and earth that belong to the native land. By creating a diptych on Awagami Japanese paper, I was able to blend the

tactile quality of cyanotype prints with the intricate details of photographic prints.

SC: So, when people see these landscapes paired with remnants from the camps, what kind of connection do you hope to make?

JN: With the Trace series, I wanted to reexamine these locations by trying to depict things that you cannot see but feel or know have historical significance. This led me to use cyanotype to capture traces of objects I found at these historical sites, like broken glass or again barbed wire, transforming them into photograms during the brightest part of the day when the light was most direct. This method differs from taking photographs; it’s more tangible and immersive and sometimes obsessive process. Photography involves a certain distance to —through the lens—whereas with cyanotype and rubbing, the contact is direct, almost like drawing or tracing history by hand. The action not only came to represent the physical landscapes but also unearthed its hidden artifacts, revealing layers of history that were once buried or forgotten. In this way, I’m not just recording history but actively uncovering it, using both photography and mixed media to bring the past into present.

SC: I was wondering if it was a deliberate choice to continue with diptychs in the Trace, like IF- NOW, especially since the two bodies of work also share a similar color palette. Was it your initial intent for both series to be presented as diptychs? I find it particularly interesting when

compared to your final body of work Witness Trees, which is distinct in that it doesn’t use the diptych format.

JN: The decision to use diptychs in the Trace series, like in the IF-NOW series, was somewhat intuitive rather than entirely planned. It evolved from my continuous exploration of themes and my approach to render the various modes of representations. In the work Traces, landscapes are paired with blue and brown cyanotypes to enhance the dialogue between two methods of exploring the past. Both series feature diptychs that enrich my personal experience and the historical narrative of the sites. In Witness Trees, I intended to transform reality into a more poetic and emotional experience, inviting viewers to stand in front of these trees and contemplate their historical significance, where in Trace, the use of diptychs allows me to establish a direct and tactile connection to history, much like tracing a memory directly onto the viewer’s consciousness.

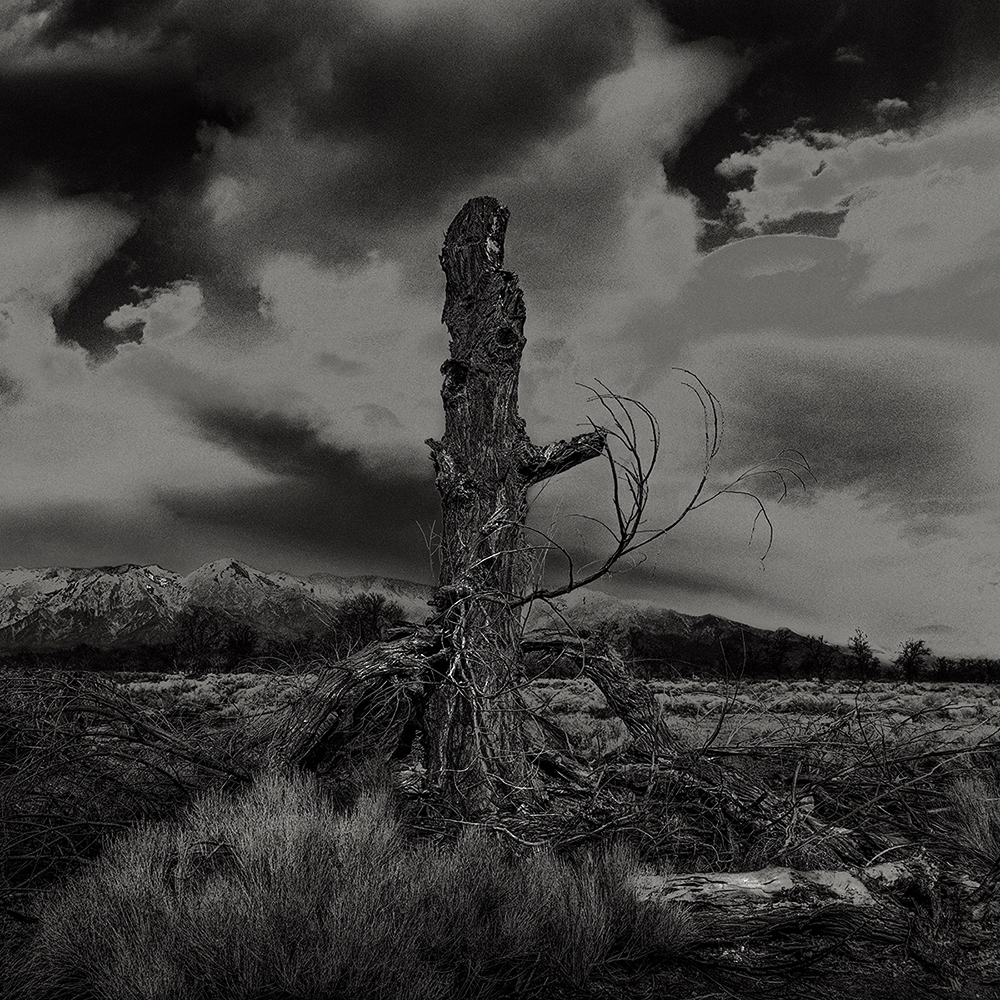

SC: What made you feel like trees were the right subject for Witness Trees?

JN: I was drawn to trees as the subject for Witness Trees during a solitary visit to the Amachi camp in southeast Colorado. It was an intensely personal experience, being alone in that vast, cold landscape. The trees at the camp seemed almost like silent observers, standing stoically by the

foundations of the camp buildings. This presence was powerful; they felt like living witnesses to the history that unfolded in that space. I felt compelled to capture them not just as elements of the landscape, but as central figures that stood watch over the area. Their enduring presence at these historic sites inspired me to use them as a focal point to convey a deeper narrative about memory and survival.

SC: Considering your description of Witness Trees, it stands out as quite distinctive among your three bodies of work, primarily because it features only black and white imagery and singular images. Was this choice influenced solely by the materials you had available, or did you deliberate over whether to incorporate additional elements? Essentially, what led you to present the trees as standalone subjects?

JN: The approach I took with Witness Trees was distinct because I used a film camera, which naturally influenced the style and feel of the images. I viewed the trees as more than just subjects; they were like historical markers or indices of the place, suggesting a presence that might have witnessed the past events there. Although it’s not strictly documentary, I personified the trees, feeling as if they were watching over or even protecting the space—and me by extension. This added a sense of companionship and security, similar to how I felt with the bats in the caves of Okinawa. Despite the eerie solitude, the presence of these natural observers made the locations feel less daunting.

SC: The way you edited the photos of the trees is really striking. What inspired you to present them the way you did?

JN: The editing style for the photos of the trees emerged from a desire to convey the profound feelings they evoked standing at the historical sites. Initially, making straightforward, beautiful prints of the trees felt too descriptive and somewhat cliché. I wanted to capture more than just their physical appearance; I needed to reflect the deep, sometimes somber history they witnessed. This led me to experiment with the images in post-production, where I adjusted the curves to create a heavier effect, enhancing the film grain and creating an almost desolate feel. The resulting tonality—somewhere between infrared, positive and negative, slightly solarized—seemed to embody the unique atmosphere of these locations. This technique helped me translate the emotional and historical weight of the scenes into something visually compelling and distinctively representative of the feeling of standing in front of these trees.

SC: One last question, knowing you for as long as I have, it’s fair to say that your work portfolio contains a broad range of themes and styles, from your Drive-in-Theatre series to Kai and Mado, and now to your more recent explorations in American Truths. What drives you to diversify your artistic approach, and how do you feel this variety influences your engagement with your audience?

JN: Yes, my artistic approaches vary quite a bit, which I know can be puzzling for those unfamiliar with my work. However, for those who have followed me for a long time, I often hear, “Here goes James, reinventing himself again!” But for me, it’s not about reinvention; it’s about building on my previous work—from the Mado to Kai series and from Banta to now. As I’ve grown older, I’ve become grateful for the opportunity to explore different styles. This diversity keeps me questioning and challenging myself, ensuring that my work doesn’t become stagnant.

The new Bob Dylan movie really resonated with me because it illustrated his transition from folk to rock despite facing criticism. This reminded me of my own shifts in style, and in American Truths it’s no different. I’m experimenting with techniques like cyanotype and black and white film to capture the essence of the invisible. Now, I am exploring alternative ways of presenting the project for upcoming exhibitions, so you see, the project is always shifting and changing with a new perspective to show. These varied approaches not only push my creative boundaries but also engage a broader audience, keeping my work fresh and relevant. I’m 62 now, and every project I’ve done has been an opportunity to explore a new perspective while staying true to my artistic roots.

Osamu James Nakagawa was born in New York City in 1962 and raised in Tokyo. He returned to the United States and moved to Houston, Texas at the age of 15. He received a Bachelor of Arts from the University of St. Thomas Houston in 1986 and a Master of Fine Arts from the University of Houston in 1993. Currently, Mr. Nakagawa is the Ruth N. Halls Distinguished Professor of Photography at Indiana University in Bloomington, where he lives and works. Nakagawa is a recipient of the 2009 Guggenheim Fellowship, the 2010 Higashikawa New Photographer of the Year, and the 2015 Sagamihara Photographer of the Year in Japan. Nakagawa’s work has been exhibited internationally, solo exhibitions include Witness Trees, PGI, Tokyo, 2023; GAMA Caves, Sepia EYE, New York, 2014; OKINAWA TRILOGY: Osamu James Nakagawa, Kyoto University of the Arts, 2013; Banta: Stained Memory, Sakima Art Museum, Okinawa, Japan, 2010; Course: Banta, SEPIA International Inc., New York, NY, 2008, and others.

Selected group shows include – Triennial of Photography Hamburg 2022: Currency: Photography Beyond Capture, Halle fur Aktuelle de Kunst-Deichtorhallen, Hamburg, 2022; From the CAVE, Tokyo Photographic Art Museum; Photography to End All Photography, Brandts Museum, Denmark, 2018; Shared Elegy: Emmet Gowin, Elijah Gowin, Takayuki Ogawa, James Nakagawa, Grunwald Gallery of Art, Indiana University, 2017; The Photograph: What You See & What You Don’t #02, Tokyo University of Arts, 2015; Infinite Pulse: Photography in Time, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2016; After Photoshop: Manipulated Photography in the Digital Age, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2012,Medialogue-Photography in Contemporary Japanese Art ’98, Tokyo Photographic Arts Museum. His work is included in numerous public collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, George Eastman Museum, Tokyo Photographic Arts Museum, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Sakima Art Museum, Okinawa, The Museum of Contemporary Photography Chicago, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Indianapolis Museum of Arts, Grand Rapids Museum of Art, and others. Akaaka Art Publisher published Nakagawa’s monograph GAMA Caves.

Instagram: @jamesnakagawa

Seth Adam Cook is an artist from the Bayou Teche region in south-central Louisiana. Drawing inspiration from the swamps and marshes of his home, his versatile studio practice often merges photography with other creative media, imbuing a deeper sense of meaning through his choice of materials and techniques. Cook earned his B.F.A. in studio art from the University of Louisiana at Lafayette in 2016 and completed his M.F.A. in photography at Indiana University, Bloomington in 2020. His work is shown nationally and internationally, including notable features in multiple publications such as Lenscratch, SHOTS Magazine, and Der Greif. He is a recipient of the 2024-2025 Faculty Fellows in Digital Humanities Collaborative Grant and the 2022-2023 GC Journeys Community-based Engaged Learning Mini-Grant. Currently a faculty member at Georgia College and State University, Cook continues to explore alternative photographic processes and serves as a contributing editor for photobook publisher Fall Line Press.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026

-

Carolina Baldomá: An Elemental PracticeJanuary 5th, 2026