The Female Gaze: Karen Klinedinst – Nature, Loss, and Nurture

©Karen Klinedinst, In the Early Morning, from the series Where I Am; archival pigment print on Hahnemühle Bamboo paper

Karen Klinedinst is a visual artist whose work explores themes of place, our relationship with nature, and the environmental impact we have on the world around us. Through digital, analog, and alternative photographic processes, she creates images and visual stories that reflect on time, memory, and the ephemerality of the natural world.

She has exhibited at Maryland Art Place, University of Maryland Global College, Center for Photographic Arts, Washington County Museum of Fine Arts (Maryland), Biggs Museum of American Art, Griffin Museum of Photography, Maine Museum of Photographic Art, and the Fort Wayne Museum of Art. Her work is in private and public collections, including the Liriodendron Mansion, the National Park Service, and the Fort Wayne Museum of Art.

Karen was an artist-in-residence at the Catskills Center for Conservation and Development, a National Park Service artist-in-residence at Acadia National Park, and a 2022 PLAYA artist-in-residence in Summer Lake, Oregon.

She is a graduate of the Maryland Institute College of Art.

Instagram: @karenklinedinst

© Karen Klinedinste, Remain In Light, from the series Tidal Dreams; archival pigment print on vellum and white gold leaf

I can’t remember when I “met” Karen Klinedinst, I only recall that it was on Facebook. Since we’ve both been significantly involved with mobile photography, I surmise it was in the early days of mobile photography in one of the FB mobile groups. I’ve come to know her personally a bit, but I never knew the story behind her work, only that she makes gorgeous landscapes.

It didn’t escape me that Klinedinst’s work looks back to the Pictorialist aesthetic. That movement, which dominated photography during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was driven by people focused on creating an emotional image rather than simply recording a documentary one. Klinedinst’s palette references paintings of the Romantic Landscape era, and her use of textures underscores the painterly look of her work. Due to her use of post-production technique using both digital and analog techniques it is also reminiscent of work done by the Brotherhood of the Linked Rings, who thought photography could be more than mechanical, and worked to push manipulations meant to make it such, while reflecting the Masonic values of Good, True, and Beautiful. Klinedinst’s work is certainly representative of those.

I hope you enjoy learning more about Klinedinst and her work as much as I did.

©Karen Klinedinst, Winter Marsh, from the series Where I Am; archival pigment print on Hahnemühle Bamboo paper

DNJ: Tell us about your childhood.

KK: Both of my parents are musicians and educators who instilled in me a profound love for music and learning. My mother taught me piano, while my father taught me clarinet. Because they offered private music lessons after school, practicing every morning before catching the bus was non-negotiable. At the time, I may not have fully appreciated this routine, but it instilled in me the discipline and dedication that I now apply to all my creative endeavors.

Although neither of my parents was a visual artist, they recognized my talent early on and prioritized nurturing it. They enrolled me in private art lessons with local artist Kas Morrett on Saturday mornings in Mechanicsburg, PA. Under her expert guidance, I learned essential skills in composition and color, which continue to influence my artistic practice today.

©Karen Klinedinst, The Secret Forest, from the series The Emotional Landscape; archival pigment print on Hahnemühle Bamboo paper

DNJ: Many people took their first photograph as children, often using cameras they owned or borrowed from their parents. If you remember when you took your first picture, did that experience influence your future passion for photography?

KK: My parents gifted me a manual Minolta SRT201 camera for my high school graduation. That summer, before I left Mechanicsburg to attend the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) in Baltimore, I took my first photography class. In this class, I learned how to shoot, develop film, and make prints. I must admit, I love the smell of photo chemicals. The first time I saw my image appear in the developer tray, it felt like pure magic! That moment made me realize that photography was the medium for me.

©Karen Klinedinst, Late Day, Late August, from the series Tidal Dreams; archival pigment print on vellum and white gold leaf

DNJ: When did you figure out art was your career path, and how did that happen?

KK: From a young age, I knew that I wanted to become an artist. By high school, I discovered the field of “commercial art” and graphic design, which led me to take several design classes. It felt like a natural fit to combine my creativity with the opportunity to earn a living. During that time, I subscribed to Communication Arts magazine and became inspired by the works of early great designers like Herb Lubalin and Milton Glaser. At the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA), I majored in graphic design while also studying photography.

After graduating, I started my career as a graphic designer and eventually became an art director. I worked for several design firms in Baltimore before moving on to educational institutions, including the University of Maryland and Johns Hopkins University. Throughout my career, I’ve had the pleasure of collaborating with talented photographers such as Susie Fitzhue, Chris Hartlove, Michael Northrup, and Steve Spartana. My background in photography has enhanced my abilities as both an art director and photo editor, while my skills as a designer and visual communicator have also improved my photography.

©Karen Klinedinst, Late Afternoon, Kent Narrows, from the series The Emotional Landscape; archival pigment print on Hahnemühle Bamboo paper

DNJ: What led you to choose MICA over other institutions? Were there any instructors there who significantly influenced you?

KK: My dream was to attend art school, so I applied to both Parsons in New York and MICA in Baltimore. During the campus tour of MICA, I stepped into the impressive Beaux-Arts Main Building with its sweeping marble staircase and instantly recognized that it was the right place for me. MICA offered me a generous financial aid package, including a scholarship that covered half of my tuition, which made my decision clear. It was a choice based on both practicality and beauty, affirming my path forward.

©Karen Klinedinst, Shenandoah Spring, from the series The Emotional Landscape; archival pigment print on Hahnemühle Bamboo paper

Two instructors had a significant impact on me during my time at MICA. Virginia Brown introduced me to the captivating work of Emmet Gowin, which inspired me to embark on a long-term project focused on photographing the oldest generation of my family members. Gowin’s early work provided valuable insights into the art of family portraiture.

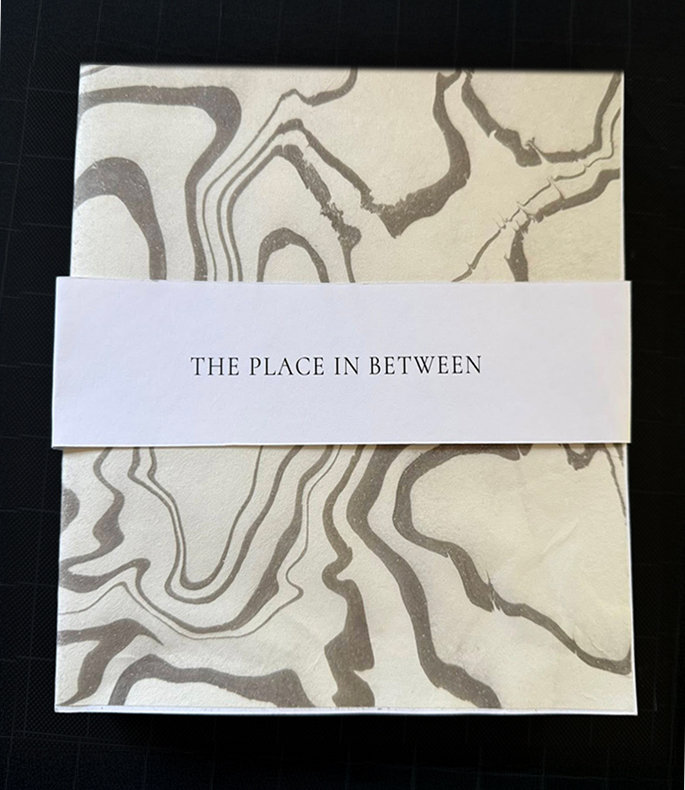

Laurie Snyder played a crucial role in expanding my knowledge of alternative and historic photo processes, such as cyanotype and Van Dyke prints. Her Artist Book class offered an excellent opportunity to combine my skills in design and photography. Recently, I revisited the notes I took during Laurie’s class while developing my latest project, “The Place In Between”, a visual and written journal that reflects my experiences during the 2022 PLAYA artist residency.

©Karen Klinedinst, Winter Birch, from the series Where I Am; archival pigment print on Hahnemühle Bamboo paper

DNJ: If you weren’t an artist, what other career would you pursue?

KK: I have no idea what I would do if I weren’t an artist; I’ve never thought about any other path. For the past ten years, in addition to creating art, I have taught photography workshops and courses for adult learners. It brings me great satisfaction to help those who may not see themselves as artists explore their creative side.

©Karen Klinedinst, Autumn, Black Water, from the series The Emotional Landscape; archival pigment print on Hahnemuhle Bamboo paper

DNJ: You’ve spent many years working with landscapes. What inspired you to create this kind of artwork?

KK: Twenty-five years ago, I completed a long-term project of photographing the oldest generation in my family. Once it was finished, I felt somewhat lost creatively. My husband, who was also an artist, suggested that I explore landscape photography, given my love for the outdoors. At the time, I was reluctant to pursue this idea because it seemed like such a well-trodden genre that I doubted I could contribute anything new. However, over time, I began to explore landscapes and their connection to memory. I became increasingly interested in how we idealize and remember a place, focusing more on the emotional aspects rather than simply documenting a scene.

Once I allowed myself to explore the landscape, I revisited how it was portrayed in both photography and painting. This exploration led me to the romantic landscapes created by the Hudson River School painters. While I prefer the immediacy of photography, the romantic landscape painters captured the emotion and poetry of a place in a way that deeply resonated with me.

“I idealize memories of places that are rapidly changing due to climate change. Could the Romantic Landscape be relevant today? Can I create something that transcends sentimentality? ” These are the questions I kept coming back to.

©Karen Klinedinst, Morning Pastorale, from the series Where I Am; archival pigment print on Hahnemühle Bamboo paper

DNJ: Over the past 5-6 years we’ve both dealt with loss and grief in our relationships (though for quite different reasons.) We’ve both used our work therapeutically, making work that delves into our inner emotions. Something I always look for when looking at art is for it to make me feel. Deeply. Profoundly.

Your husband had a pancreatic cancer diagnosis and then passed away a few months later. I lost my mother to pancreatic cancer in 2014; she passed 5 weeks after diagnosis. It’s utterly shocking how stealthy this disease usually is—one day everything is fine, and the next people’s lives—as well those of their loved ones—are turned upside down.

Before Dan passed, it always seemed to me that your work was tied to activities you shared with your husband, such as hiking or camping. Yet, after his passing, you continued to create new images of the landscape. Has your work changed in any way due to this profound loss and its impact on your life?

KK: On August 26, 2021, my husband Dan was diagnosed with Stage IV pancreatic cancer. He passed away four and a half months later, on January 13, 2022, at home in his studio, surrounded by his artwork. We were both artists, married for 30 years and together for 36. We supported each other in all aspects of our lives, including our art.

Dan had a deep knowledge of art history and introduced me to the works of Caspar David Friedrich and George Inness—painters I was unfamiliar with when I attended art school in the 1980s. Both artists explored their spiritual connection to the landscape, which has significantly influenced my work. Dan’s love for me and respect for my art empowered me to create the pieces I do. Even after his passing, he continues to inspire my creations.

Dan and I complemented each other well. He focused on details, while I tended to see the big picture. When we hiked together, I captured broader views and the sense of place in my photographs, while he noticed small details like rocks, feathers, little animals, and plants. Since his passing, my work has taken new directions. This shift wasn’t a conscious choice; it has been a natural evolution. I am now experiencing places in the way Dan did, paying attention to the small details and incorporating foraging into my creative process.

©Karen Klinedinst, Along The Pond, from the series Where I Am; archival pigment print on Hahnemühle Bamboo paper

DNJ: In your writing about your work, you express a deep spiritual connection to the land and landscape. Could you elaborate on that? Where do your ideas originate? What do you hope the viewer takes away from your work?

I’m an unabashed romantic and see both an aesthetic and a spiritual value to the landscape. Because I experience a landscape through walking, I have an intimate view and emotional connection to certain places.

The Hudson River School painters significantly influence my landscape work. They idealized a vanishing wilderness as the country, in the first third of the 19th century, moved from an agrarian to an industrial society. When I create a romantic landscape, I’m also romanticizing and idealizing the memory of places I’m connected to, as these landscapes rapidly transform due to climate change.

The ideas that guide my work are deeply rooted in the practice of walking. This essential activity strengthens my connection to nature and influences my creative vision. Through walking, I engage intimately with the natural world, discovering inspiration in its rhythms and impermanence.

All of my projects share a common theme: our response to nature. I encourage viewers to reflect on their relationships with time, loss, and the constantly changing environment around them.

©Karen Klinedinst, Autumn,Tuckahoe Creek, from the series The Emotional Landscape; archival pigment print on Hahnemühle Bamboo paper

DNJ: You work with various styles in photography. Do you always begin a project with a clear concept, or do you prefer to shoot and let the images guide you in uncovering the project’s direction? How do you decide which process or style is most suitable for a particular project?

KK: My projects typically develop organically. I may start by exploring a photographic process or a specific location, and over time, a project reveals itself to me. Once I sense that I have a project to pursue, I write a rough project statement. This helps me organize my thoughts and makes me more mindful of how I will approach the project and what I will shoot.

My work is highly process-oriented, with the nature of the project guiding the process. For my romantic landscape series, I primarily shoot in digital format and engage in extensive post-processing. I layer colors and textures to evoke the poetry and spirituality I experience in each specific location.

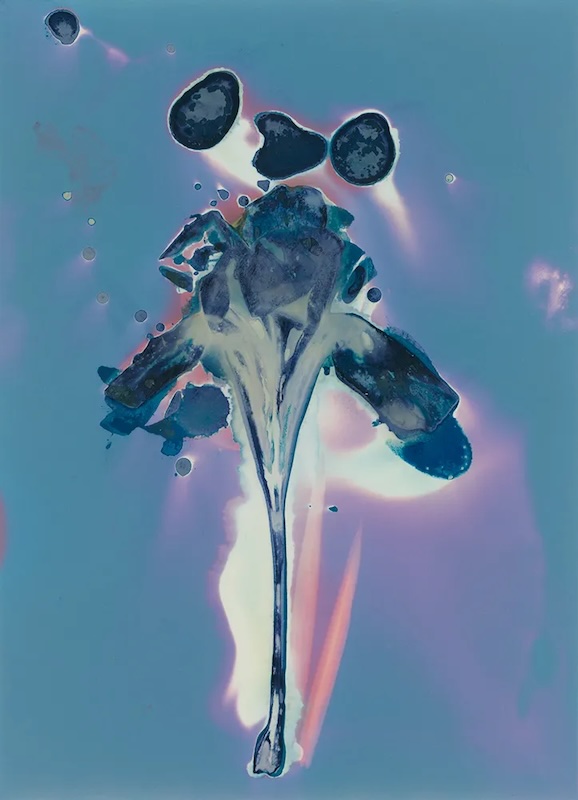

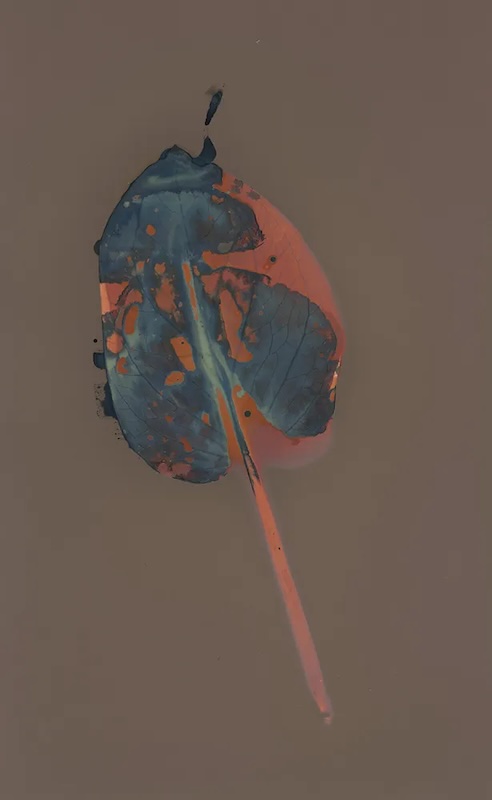

©Karen Klinedinst, Trillium, from the series Ephemeral/Ephemerals; archival pigment print on paper from original cyano-lumen

I just finished the “Place In Between” series from my time as a 2022 PLAYA artist-in-residence. The series was photographed digitally and processed in black and white, marking the first time I’ve worked in black and white in 30 years. My decision to process the images in black and white was a response to the stark, barren landscape and the profound loneliness I experienced while there.

In recent years, I have been exploring alternative and historical photo processes, such as lumens, cyano-lumens, and cyanotypes. These techniques have been integral to my work, particularly in the “Ephemeral/Ephemerals” and other botanical series, which reflect themes of time, memory, and the fleeting nature of the natural world.

©Karen Klinedinst, Skunk Cabbage and Spring Beauties, from the series Ephemeral/Ephemerals; archival pigment print on paper from original cyano-lumen

DNJ: The connection with loss and the brevity of life is so clear in the Ephemeral/Ephemerals series. How did you get started down this path? Did it begin as cyano-lumen as the concept to present your idea, or did it evolve to that as the project developed? Does making the final work a pigment print change the meaning for you?

KK: As his final Christmas gift to me in December 2021, Dan paid for and enrolled me in the Plant-based Photo Printmaking 12-session class that Ann Eder taught through Harvard University. The class started 10 days after Dan passed away. I considered cancelling; I’m so glad that I didn’t. Eder is such an inspiring teacher, and her class helped me channel my grief into something positive. I learned the lumen and cyano-lumen processes during that class.

During my spring hikes since Dan died, I have searched for and collected ephemerals emerging from the forest floor. I use the cyano-lumen process to honor the essence of these brief, beautiful lives. Walking has always been essential to my creative process, but it has also become a vital means of processing my grief. Walking compels me to slow down and look for signs of life after a long, dark winter, mirroring my journey through grief and towards new life. The “Ephemeral/Ephemerals” series started as a form of personal art therapy, exploring a new photo process. But by the end of the course, I had a body of work and a working project statement that I’ve since expanded upon.

©Karen Klinedinst, Skunk Cabbage, from the series Ephemeral/Ephemerals; archival pigment print on paper from original cyano-lumen

After dipping the foraged plants in cyanotype sensitizer, I create a composition on long-expired black and white darkroom photo paper discovered in my studio, giving this old paper new life. The photo paper is then exposed to the sun’s ultraviolet light, embracing the unpredictability of weather and lighting conditions, and requiring me to relinquish control. This process is filled with surprises and serendipity, and a meditation on finding the beauty in impermanence.

The resulting cyano-lumens are scanned, capturing a moment in time. When I shared small work prints from this body of work to a crit group that I belong to, it was suggested to me that the images should be much bigger. I always envisioned them as small, intimate expressions of life. I’ve since had 40″ pigment prints made from scans of the original cyano-lumens. These large prints transform these plants from the intimate into beings, separate from my experience. Their beauty and essence shine through.

The original cyano-lumens remain chemically unfixed and are themselves ephemeral, destined to change over time. They are stored in a black bag inside a black box tucked away in my studio. I occasionally take a quick look at the originals to witness the subtle changes. My long-term plan is to create an artist book using the original cyano-lumens—a beautiful place for the unfixed prints to live and change.

©Karen Klinedinst, Virginia Bluebells No. 2, from the series Ephemeral/Ephemerals; archival pigment print on paper from original cyano-lumen

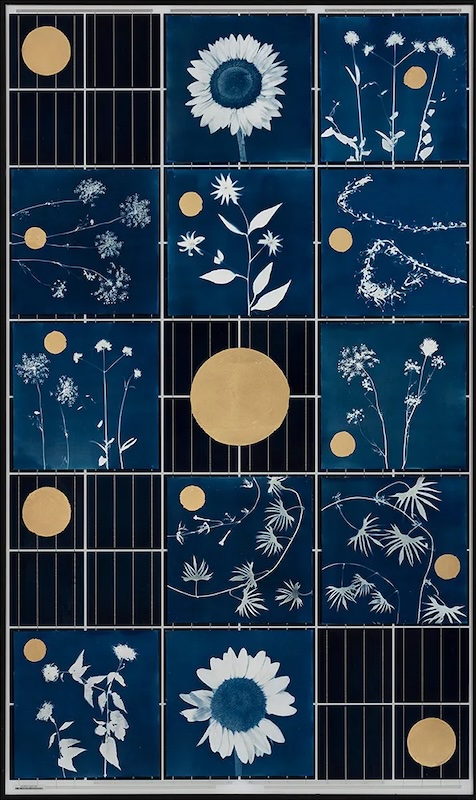

Regarding All Flowers in Time Bend Towards The Sun, you write: “This work incorporating a recycled solar panel was commissioned by Maryland Art Place for the reGENERATE exhibition. Inspired by Anna Atkins, the English botanist, I used foraged flowering plants and the cyanotype process to celebrate the power of love and resilience despite grief and loss.” That surprised me. I had seen the work on social media (without the statement) and surmised due to the content and media that it was about the climate crisis. Tell me about the connection between the idea, the media, and the meaning.

KK: Last summer, I was one of nine artists commissioned by Maryland Art Place to create a work using a recycled solar panel for the “reGENERATE” exhibit, themed around renewal and regeneration. “All Flowers In Time Bend Towards The Sun,” explores renewal after loss. I foraged plants from a city park and created a series of 11 cyanotypes using sunlight during the longest days of the year.

This work reflects my personal journey after losing my husband, while also resonating with the universal experience of grief and the pursuit of love and light. Creating it was a challenge, as I rarely work on commission and had to step outside my comfort zone. I researched extensively and refined my idea before executing the final piece.

In February, I faced another loss when the artwork was stolen from my studio hallway. The emotional weight of losing such a significant piece felt like a death. After weeks of searching and filing a police report, I was overjoyed to learn that it was found in the closet of a new tenant at the Mill Centre. The work was due to be exhibited in two days, but I discovered that the gold leaf had been scraped off. I re-gilded it then dropped it off for the show. The scars of its history now coexist with the new gilding, symbolizing the cycle of loss and renewal.

©Karen Klinedinst, All Flowers In Time Bend Toward The Sun; multiple cyanotypes on paper and gold leaf on solar panel, 40×70″

DNJ: What is next on the horizon for you?

KK: In 2026 (exact dates to be announced), I will exhibit the “Ephemeral/Ephemeral” series for the first time as a solo show, and I plan to continue working on the series next spring, creating new cyano-lumens.

I recently completed a 32-page double-sided French-fold accordion artist book prototype titled “The Place In Between,” based on my experiences during a two-week residency at PLAYA in Summer Lake, Oregon, in November 2022. This was just ten months after my husband’s death, and I found it challenging to be in such a remote place without my support system. During that time, I created a visual and written journal that captures this significant moment in my life. It took over three years and many revisions to finalize the work, which has been an emotional journey. I am now preparing to show the prototype to curators and the public.

©Karen Klinedinst, The Place In Between; handmade prototype of photo book. Editorial Note: Here is a link to Klinedinst’s page-turner video of the book prototype. It’s beautiful, and you can feel the emotions she describes come through the pages of the book.

DNJ: Thank you ever so much, Karen, for sharing your practice and your life’s journey with our readers. I’ve learned so much about your work, and I truly look forward to seeing the evolution of the book!

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

South Korea Week: Yi Wan Gyo: Nirvana-Beyond DarkJanuary 13th, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Han ChungShik: GoyoJanuary 12th, 2026

-

Carolina Baldomá: An Elemental PracticeJanuary 5th, 2026

-

Dawn Roe: Super|NaturalJanuary 4th, 2026

-

Marcia Molnar: The Silence of WinterDecember 24th, 2025