Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: George Nobechi (2021) and Ingrid Weyland (2022)

Photolucida is a Portland-based nonprofit dedicated to providing platforms that expand, inspire, educate, and connect the national and international photography community. Critical Mass, Photolucida’s annual online program, is designed to foster meaningful connections in the photography world. Open to photographers at all levels, anywhere in the world, participants submit a portfolio of 10 images. Following an initial pre-screening, 200 finalists are selected to have their work reviewed and voted on by up to 200 distinguished international photography professionals. From this process, the Top 50 are chosen, and a range of awards is presented. Submissions open each June.

In 2025, we celebrate the twentieth year of announcing the Critical Mass Top 50 finalists! We are honored to partner with Lenscratch to reflect on this history through a special series highlighting two artists from two different years in each post. Each featured artist offers a window into the diversity of projects and voices that make up Critical Mass—from documentary and narrative photography to conceptual, photo-based practices. These Q&As share the history, intention, and trajectory of the artists, pairing their Critical Mass portfolios with newer work.

For Critical Mass 2025, we received submissions from artists across 26 countries, tackling subjects in countless styles—from black-and-white and digital photography to chemigrams, cyanotypes, photographic sculpture, and textiles. Our esteemed jurors, representing a wide range of global perspectives, dedicate their expertise and thoughtful consideration to this process, often leaving feedback and encouragement for the artists.

Critical Mass continues to elevate emerging photographers, providing a platform that amplifies their voices to broader audiences and to the industry professionals who help shape careers. We are deeply grateful to everyone who makes this possible.

George Nobechi 2021

George Nobechi’s photography lives in the space between memory and myth, weaving everyday details with timeless allegory. Twice named a Critical Mass Top 50 artist, his series The Japan I Hadn’t Seen reflects on distance, rediscovery, and the search for home. Drawing on childhood visits to aquariums, his grandfather’s storytelling, and the surreal writings of Kenji Miyazawa, Nobechi creates images that balance tenderness with tension—what the Japanese call natsukashisa and setsunasa. In this conversation, he reflects on his creative influences, the role of cultural context, and what Critical Mass has meant for his artistic journey.

George Nobechi‘s work is often described as evoking solitude, duality and longing. As a bicultural Japanese/Canadian he is simultaneously an insider and outsider in both Eastern and Western cultures and this is reflected in his sensibility and vision.

Nobechi was born in Tokyo to a Canadian father and Japanese mother. His Japanese grandfather, a high school teacher on the northern island of Hokkaido, was his role model and nurtured a thirst for knowledge across the arts, science and history. Those influences remained with Nobechi as his family moved to Canada when he was eleven. During his studies at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, his father suddenly died, and upon graduation with an Honors Degree in History and International Relations in 2002, Nobechi entered the world of Finance, first in Tokyo and later in New York.

Along the way, Nobechi began to feel disconnected from life and embarked on solo round-the-world journeys in 2008 and 2010 in order to try to cross that void. In 2014 while living in New York, he was inspired by the Photoville photo festival and decided to walk away from his career. He placed his belongings in storage, gave up the lease on his apartment, and traveled to the Southwestern US to study photography, first under Brett L. Erickson, and continuing as an intern at the Santa Fe Photographic Workshops in 2015, where he met the National Geographic photographer Sam Abell. Abell identified the potential in Nobechi and suggested he pursue a career in photography. What followed was a three-year journey with no fixed home. As the months and years passed, Nobechi felt a beckoning from his homeland and he returned to rediscover Japan from his newfound perspective as a photographer.

Since 2020 he has been involved in community and philanthropic work, creating the series Evenings with the Masters©, which showcases international master photographers and raises funds for charity; to date, he has interviewed 36 photographers such as Pete Souza, Michael Kenna, Jane Evelyn Atwood, Arno Rafael Minkkinen, Mona Kuhn, Awosika van der Molen, Greg Gorman, Kate Breakey, raising over $70,000 for charity.

In 2022, Nobechi was chosen to represent Japan in the Fujifilm documentary series “Reflections.” In 2023, he co-founded Karuizawa Foto Fest, a new developmental ground for photographers from around the world. He remains Creative Director of KFF.

Awards, Galleries, Exhibitions, Publications, Collections Highlights

Gallery representation: Nobechi is currently represented by Patricia Conde Galeria (Mexico) and the Webster Collection (Santa Fe, NM) and was formerly represented by A Gallery for Fine Photography (New Orleans)

Solo exhibitions: Recent solo shows include “Roads to Denali” FUJIFILM Square Tokyo 2023, “The Japan I Hadn’t Seen” FotoNostrum, Barcelona 2023, “Phoenix Rises” Hiroshi Senju Museum Karuizawa 2023, “Eastern Light, Western Wind” Frederick Harris Gallery Tokyo 2023 and Photoville New York 2020.

Collections: Nobechi’s work is included in the collections of the Center for Creative Photography, Tucson, Detroit Center for Contemporary Photography and the Australian Museum of Contemporary Photography.

Publications: Nobechi’s photographs and words have been published in Huffington Post, Newsweek Japan, Fuji Koron, Tokyo Shimbun, PDN, Lenscratch, Dodho, Fraction, Asahi Camera & Vostok

Awards: Highlights include: Critical Mass Top 50 (2017, 2021), Critical Mass Finalist (2016, 2017, 2020, 2021, 2023) Rfotofolio winner 2018, Review Santa Fe selection 2018, PX3 Paris Photo Prize Silver for monograph and fine art categories 2017, International Photo Awards Bronze winner series 2018, PDN’s The Curator Award best landscape series 2017, Phoenix Art Museum’s Sidney Zuber Award Honorable Mention 2017, SilverEye Center for Photography’s Commendation Award 2017, PRC Boston’s Exposure Award 2017. PX3 State of the World Curator Selection Winner 2020, Rfotofolio Merit Award winner 2020, Kolga-Tbilisi Photo Festival Best Single Shot 2020 Finalist. Also a World Press Photo 6×6 Asia Shortlist nominee in 2020 and PDN 30 Nominee in 2018.

Instagram: @georgenobechi

Q: Can you tell us how you first learned about Photolucida’s Critical Mass, and what motivated you to enter?

GN: I first heard about Critical Mass in 2015 from photographer Amy Toensing, but the next entry window wasn’t until 2016. I had only just started photography, and through sheer luck made it into the Top 200, though not beyond. I studied the Top 50 closely, revised my work, and in 2017 made the Top 50 for the first time.

Q: Your 2021 Critical Mass Top 50 portfolio The Japan I Hadn’t Seen grew from returning to Japan after years away. How did that distance shape your photography?

GN: Stepping away allowed me to see Japan anew. I began noticing small, everyday details—neighbors sweeping the streets, a casual ohayo gozaimasu exchanged on the way to work. Those simple gestures, often overlooked, became central to my images.

Q: You describe feeling like the protagonist in the folktale Urashima Taro. How does that story resonate with your work?

GN: Urashima Taro is a tale of kindness, indulgence, and consequence. He saves a turtle, enjoys a lavish party under the sea, then opens a forbidden box he cannot resist. To me, it’s a universal reminder of human folly. Myths like this are always in my subconscious—I use them as visual metaphors. Viewers don’t need to know the stories, but if they bring their own imagination and memories, the connections will emerge.

Q: The series draws inspiration from your grandfather’s storytelling and the surreal works of Kenji Miyazawa. How do literature and memory shape your practice?

GN: My grandfather was a teacher who instilled in me curiosity about science, nature, and stories. He introduced me to Miyazawa, whose magical realism—both whimsical and dark—has deeply influenced Japanese culture. His writing inspired me to explore liminal spaces between the ordinary and the fantastic, which I try to capture in my photographs.

Q: Since beginning the project in 2015 and relocating to Japan in 2017, how has your sense of “home” evolved?

GN: For years I drifted from place to place. It wasn’t until 2021 that I felt I’d truly put down roots. My images reflect that constant searching—stones rolling restlessly rather than gathering moss. The Japan I Hadn’t Seen is less about finding home than about seeking it.

Q: How did your early visits with your grandfather to the Otaru aquarium influence this series and your approach to memory?

GN: In Japanese, natsukashisa refers to a fond memory triggered in the present—different from nostalgia, which longs for the past. My work is rooted in natsukashisa: appreciating the moment for how it connects past and present. My time with my grandfather lives on this way, not just as memory, but as a daily influence.

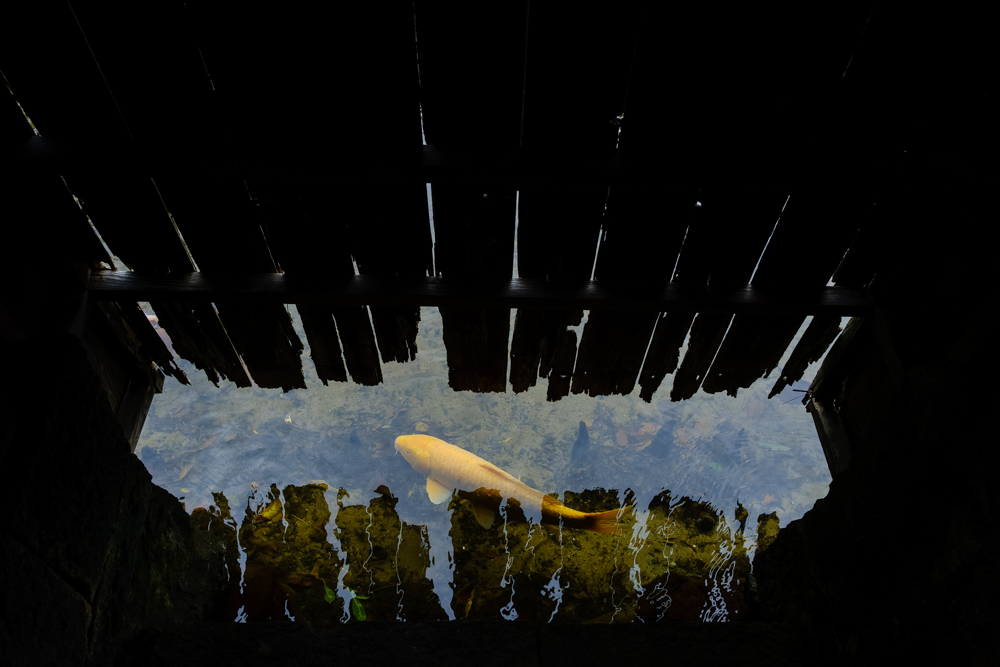

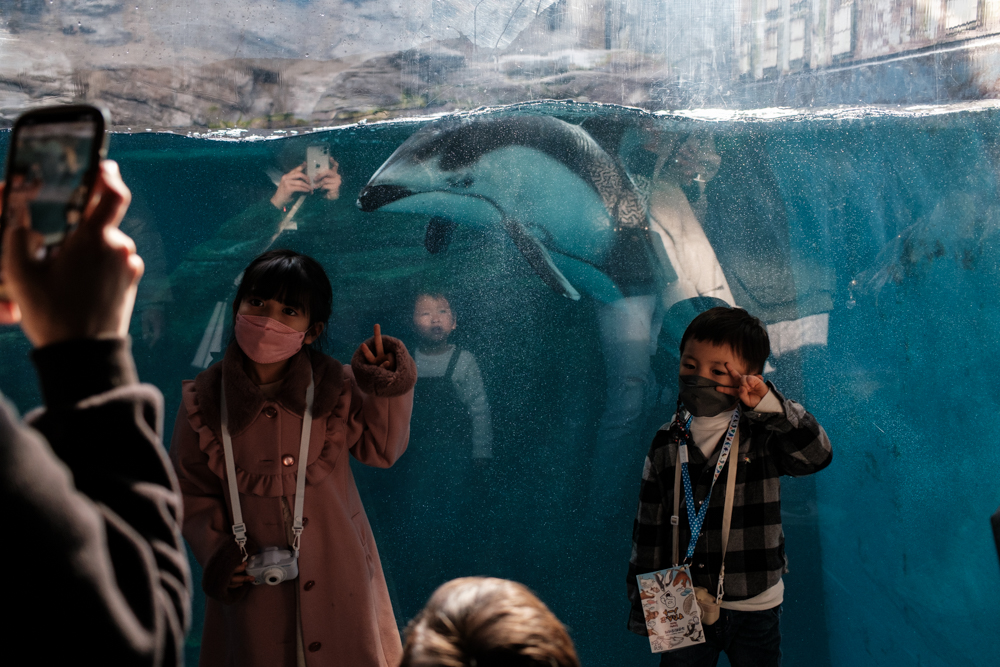

Q: How does your Japanese Aquariums series navigate the tension between childhood wonder and animal welfare?

GN: There’s a word for this too: setsunasa—a sweetness laced with sorrow. Aquariums stir joy and childhood memories, but also pity for animals confined. I want my images to hold that duality and let viewers feel whatever arises—delight, sadness, even anger.

Q: You’ve said Japanese design contributes to the surreal mood of aquariums. Can you expand on that?

GN: Japanese design often places viewers on a threshold, like the viewing platform at Ryoanji’s stone garden—both inside and outside. Aquariums are designed similarly: with tunnels, bubble glass, escalators through tanks. They immerse you while keeping you at a contemplative distance, creating a surreal experience I aim to capture.

Q: With many aquariums shifting toward conservation, what do you hope your photographs leave with viewers?

GN: Thought and emotion. Like Garry Winogrand’s The Animals, I want these images to provoke reflection on the human condition, on how we relate to other beings, and on the future of such spaces.

Q: Finally, did recognition as a Critical Mass Top 50 artist open opportunities for you?

GN: It wasn’t a golden ticket. After my first Top 50 in 2017, the phone didn’t suddenly ring with offers. But it gave me confidence to show my work, which led to exhibitions, publications, and growth. At the same time, I’ve been told I was “playing at photography”—so the journey is humbling too. My friend Eiji Ohashi, who was also selected that year, built remarkable success from his series. My path has been more varied—artist, creative director, festival director—but deeply fulfilling.

Winning again in 2021 quieted my imposter syndrome. Editors in Japan sometimes say my work is “too everyday,” yet galleries embrace it. Recognition through Critical Mass affirmed that audiences exist, even if they are unexpected ones. Above all, submitting itself takes courage. Even reaching the Top 200 means your work is seen by incredible jurors, and that visibility matters. I’m grateful for the doors it opened, and honored to now serve as a juror myself.

Ingrid Weyland 2022

In Topographies of Fragility, Ingrid Weyland transforms photographs of remote landscapes into sculptural objects, their folds and creases echoing the scars left on the Earth. A Critical Mass 2022 Top 50 finalist, the series moves between reverence and warning—celebrating nature’s sanctuaries while confronting their vulnerability. In this interview, Weyland reflects on the project’s origins, her process, and the opportunities that recognition has opened.

Argentinian artist Ingrid Weyland was inspired to study graphic design given her exposure to architecture and sculpture, as well as her passion for manipulating form and composition. Following her studies at the University of Buenos Aires (UBA), she set up her own practice, BW Design. Photography and image creation captured her imagination, and by 2011 she dedicated herself to perfecting her craft through workshops with Ana Sánchez Zinny, Angela Copello, Fabiana Barreda, Julieta Escardó, Juan Brath, Proyecto Imaginario, and Verónica Fieiras, among others. Her practice evolved from portraiture to an immersive exploration of pristine landscapes across several continents.

Since dedicating her artistic process to photography, Weyland has received recognition from many global sources, including Decade of Change by 1854 British Journal of Photography, Exposure Photo Festival in Calgary, the Ashurst Emerging Artist Photography Prize (2021), as well as being a finalist in the Discovery Awards – Encontros da Imagem in Braga, the LensCulture Critics’ Choice, and the Rhonda Wilson Award. In 2022, she was shortlisted for the Aesthetica Art Prize (UK), Photolucida Critical Mass Top 50, and was a Juror’s Pick in the LensCulture Art Photography Awards. In 2023, she was the Americas winner of the Saatchi Art for Change Prize (UK). She also got nominated for the 2025 Prix Pictet.

Q: Can you tell us how you first learned about Photolucida’s Critical Mass, and what motivated you to enter?

IW: I first learned about Critical Mass while attending Photolucida’s Portfolio Review, which I joined after receiving Klompching’s Rhonda Wilson Award. Many of the artists I met there had either participated in Critical Mass or spoke highly of it, encouraging me to apply. It struck me as an incredible opportunity—not only for broader exposure but also to connect my work with a wider community of curators, reviewers, and peers. Their enthusiasm motivated me to enter, and I’m so grateful I did.

Q: In your Critical Mass 2022 Top 50 finalist portfolio, Topographies of Fragility, you describe the landscapes as sanctuaries that invite contemplation and introspection. How do you balance your personal, almost spiritual connection to these places with the conceptual framework of environmental commentary in the series?

IW: For me, the work begins with a deeply personal relationship to the landscape. These places feel like sanctuaries—spaces where I can slow down, listen, and reflect. That spiritual connection anchors the series emotionally.

Over time, though, I also became increasingly aware of the need to protect these fragile environments. On my third trip to Iceland, I witnessed the careless impact of tourism, which made me want to create a body of work that not only conveys the serenity of these landscapes but also calls attention to their vulnerability.

The physical act of folding, creasing, and reshaping the prints bridges those two impulses: my reverence for the natural world and a commentary on its fragility under human pressure. The emotional resonance guides the process, while the conceptual framework shapes how that resonance is expressed.

Q: The act of crumpling your prints transforms the photograph into both subject and object. Do you consider this gesture a destructive act, a creative act, or something that exists in the tension between the two?

IW: At first, the gesture felt destructive—almost violent. I was tearing into images of landscapes that had given me so much in terms of healing and reflection. It felt as if I were destroying my own memories.

But as I sat with that action, I realized it carried meaning. By physically altering the prints, I was acknowledging their fragility while also creating something new. What began as destruction evolved into a creative act, one that lives in the tension between the two.

Q: Your project spans environments from Cape Horn to the Arctic. How did the contrasts between these extremes of landscape influence the way you conceptualized fragility and resilience?

IW: Working at both ends of the Earth made me acutely aware of how fragility and resilience coexist. These are parallel extremes—remote, harsh, and seemingly eternal, yet deeply vulnerable. Standing in such vastness, I felt both awe and unease, a reminder of how exposed and delicate these places are.

The poles are critical to the planet’s balance: they regulate climate, drive ocean currents, and store ice that affects sea levels worldwide. What happens there resonates everywhere.

For me, fragility is not weakness but heightened sensitivity, which makes these landscapes unique and irreplaceable. Their resilience is real but not limitless—a truth that became central to the work.

Q: By manipulating the printed image, you highlight photography’s dependence on paper as a material derived from trees. Was this ecological self-awareness always part of your process, or did it emerge only through the accident of discarding prints?

IW: The ecological dimension emerged gradually. Initially, crumpling prints was practical: I needed space in my studio, and I didn’t want to throw away test prints I couldn’t keep. Only later did I realize the act carried weight.

Discarding the paper confronted me with photography’s materiality—the fact that these images, born of nature, are printed on paper derived from trees. That awareness deepened the work, adding another layer to its environmental commentary.

Q: The creases, folds, and ruptures in your prints echo scars left on the Earth by human intervention. How intentional are these marks in your process? Do you choreograph them carefully, or allow them to emerge unpredictably?

IW: I let the marks emerge naturally. The paper resists, evolves, and eventually settles into a form that feels right. Before working, I reflect on the memory of being in that landscape—often full of peace and wonder—yet the gesture that follows involves folding, creasing, or damaging the print. That contradiction matters to me.

Whenever I try to force a shape, it fails. Instead, I approach the paper as part of a conversation: sometimes gently, sometimes aggressively, always allowing the material to respond. The process feels performative, a negotiation between my hands and the object.

Q: You note that the works can feel like both a tribute and a farewell to natural havens. How do you hope viewers emotionally navigate this duality of reverence and loss?

IW: I hope viewers can hold both emotions at once. The series is both a tribute—an invitation to pause and feel wonder—and a farewell, an acknowledgment of what may slip away.

I don’t want viewers to resolve that tension but to inhabit it, to feel both reverence and quiet sadness. If the work prompts reflection on their own experiences in nature and lingers with them afterward, then it has done its job.

Q: In many ways, the series blurs the boundary between photography and sculpture. How has working in this hybrid space changed your understanding of photography’s role as a medium of environmental dialogue?

IW: Once the print is folded or reshaped, it ceases to be only an image and becomes an object—something scarred by touch. The medium itself becomes part of the message, the creases and ruptures echoing ecological wounds.

This hybrid process shifts photography from a window onto nature to a material language that speaks about it. It embodies instability rather than just pointing to it, reinforcing the link between body, material, and environment.

Q: You write about the Earth’s capacity for regeneration and balance after destruction. Do you see your practice as an act of mourning, or as a form of hope—perhaps even a call for restorative action?

IW: I see it foremost as a call for restorative action. The series reflects on the damage we inflict but also points to nature’s capacity for renewal—if we give it the chance.

For me, hope is active, not passive. It requires engagement and small changes that, together, can make a difference. My work is meant to encourage that sense of possibility and responsibility.

Q: Finally, did being recognized as a Critical Mass Top 50 artist create opportunities for you—either immediately after the honor or over the long term?

IW: It’s difficult to draw a precise line, but I do believe the recognition opened doors. Some opportunities came quickly—for example, one of my images appeared in Harper’s Magazine in September 2022—while others unfolded gradually through articles, interviews, and publications.

What I value most is how Critical Mass builds both immediate visibility and long-term credibility. Even now, the recognition continues to strengthen my profile and create connections that might not have been possible otherwise.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Shane Hallinan: The 2025 Salon Jane Award WinnerFebruary 12th, 2026

-

Greg Constantine: 7 Doors: An American GulagJanuary 17th, 2026

-

Yorgos Efthymiadis: The James and Audrey Foster Prize 2025 WinnerJanuary 2nd, 2026

-

Arnold Newman Prize: C. Rose Smith: Scenes of Self: Redressing PatriarchyNovember 24th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Cathy Cone (2023) and Takeisha Jefferson (2024)October 1st, 2025