Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Preston Wadley (CM 2007) and Ian van Coller (CM 2008)

Photolucida is a Portland-based nonprofit dedicated to providing platforms that expand, inspire, educate, and connect the national and international photography community. Critical Mass, Photolucida’s annual online program, is designed to foster meaningful connections in the photography world. Open to photographers at all levels, anywhere in the world, participants submit a portfolio of 10 images. Following an initial pre-screening, 200 finalists are selected to have their work reviewed and voted on by up to 200 distinguished international photography professionals. From this process, the Top 50 are chosen, and a range of awards is presented. Submissions open each June.

In 2025, we celebrate the twentieth year of announcing the Critical Mass Top 50 finalists! We are honored to partner with Lenscratch to reflect on this history through a special series highlighting two artists from two different years in each post. Each featured artist offers a window into the diversity of projects and voices that make up Critical Mass—from documentary and narrative photography to conceptual, photo-based practices. These Q&As share the history, intention, and trajectory of the artists, pairing their Critical Mass portfolios with newer work.

For Critical Mass 2025, we received submissions from artists across 26 countries, tackling subjects in countless styles—from black-and-white and digital photography to chemigrams, cyanotypes, photographic sculpture, and textiles. Our esteemed jurors, representing a wide range of global perspectives, dedicate their expertise and thoughtful consideration to this process, often leaving feedback and encouragement for the artists.

Critical Mass continues to elevate emerging photographers, providing a platform that amplifies their voices to broader audiences and to the industry professionals who help shape careers. We are deeply grateful to everyone who makes this possible.

Preston Wadley 2007

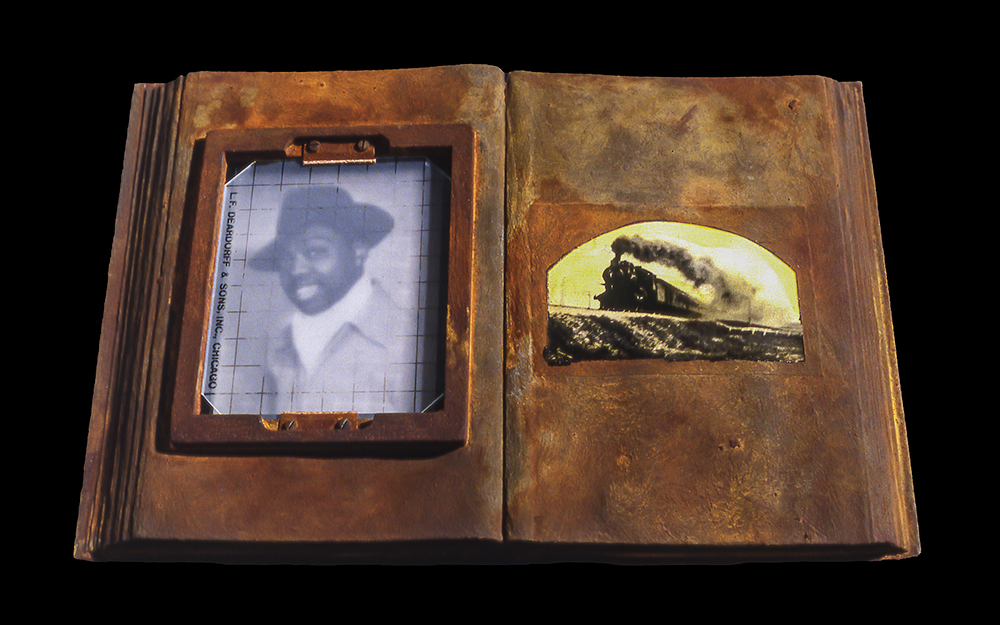

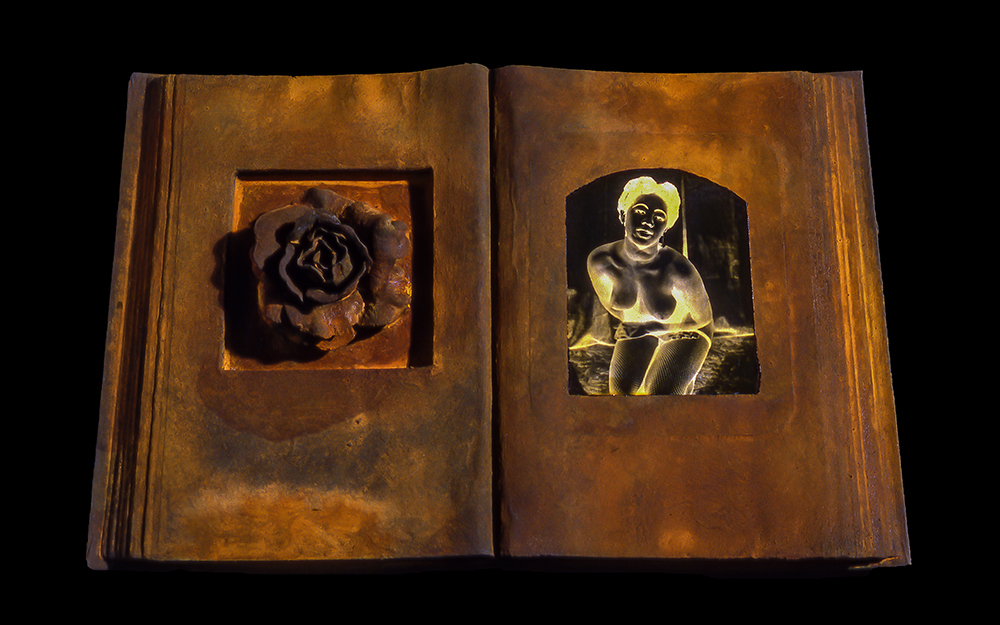

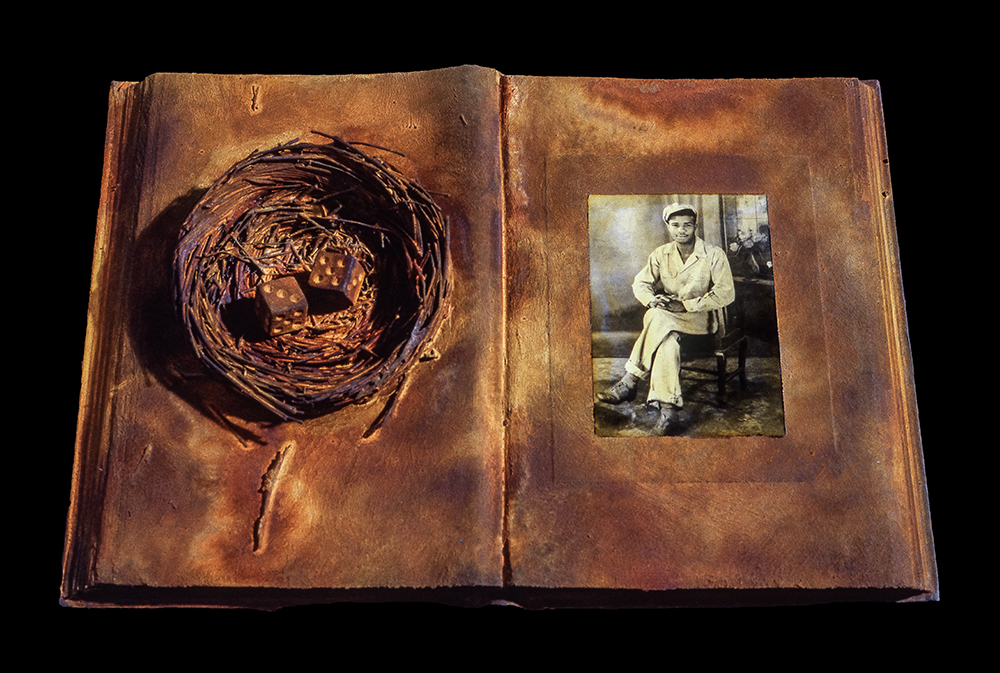

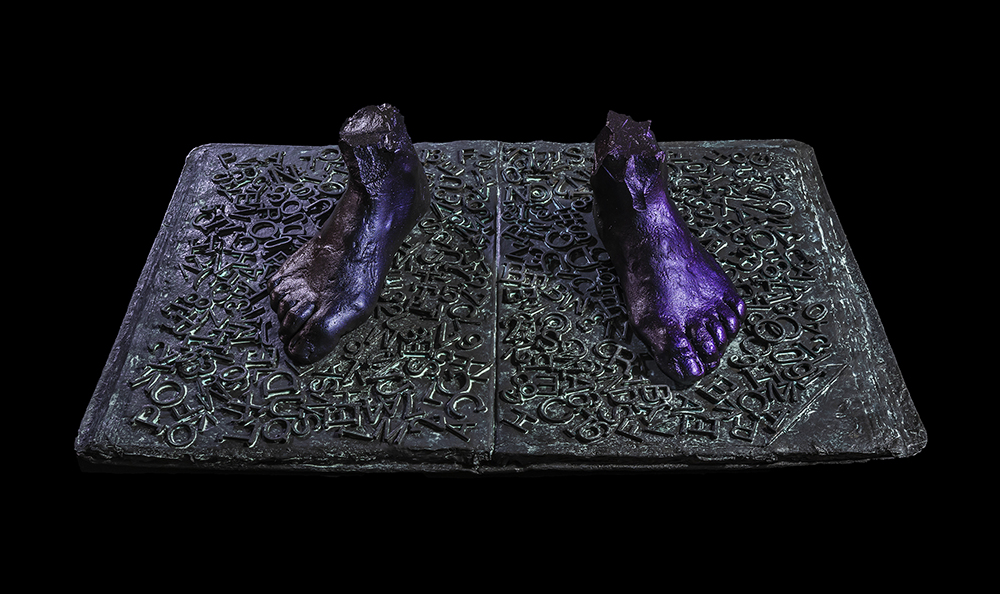

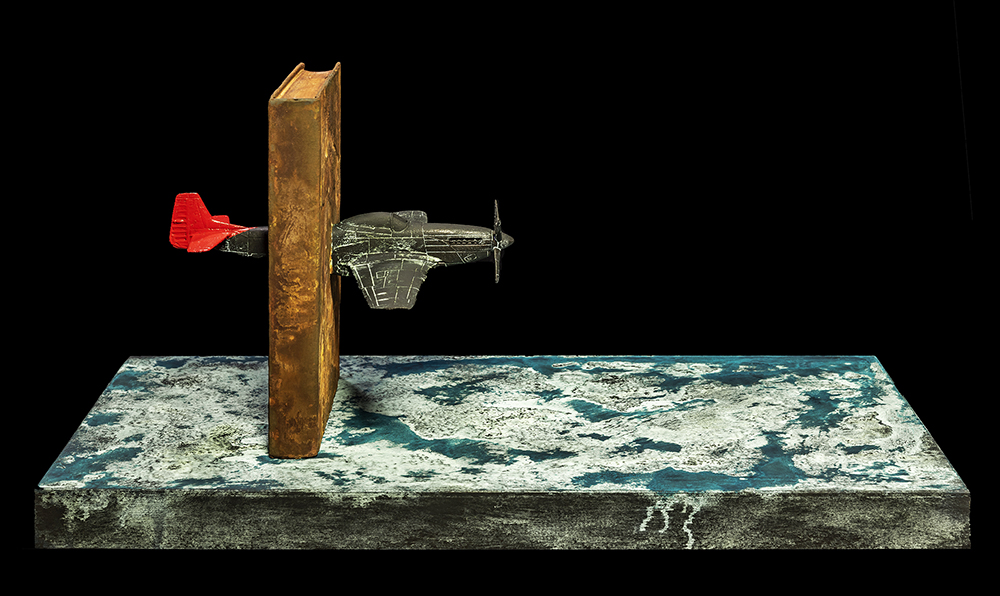

Preston Wadley’s work sits at the crossroads of photography, literature, and sculpture—objects that invite viewers to “read” them as much as look at them. Since first entering Photolucida’s Critical Mass in 2007, his practice has expanded in scale and sophistication, blending books, images, and found objects into three-dimensional forms that carry both cultural familiarity and layered metaphor. With themes of colonialism, Black community, and personal narrative running through the work, Wadley aims not simply to be seen but to catalyze thought, asking audiences to participate in the act of meaning-making. In this conversation, he reflects on the origins of his sculptural practice, the role of titles and semiotics in his process, and how the work continues to evolve with the resonance of blues music and haiku poetry.

Preston Wadley, born in Los Angeles, CA, is an artist and educator working in Washington State. He received his MFA from the University of Washington. Wadley’s projects have twice been selected to Photolucida’s Critical Mass top 50 and is currently Professor Emeritus at Cornish College of the Arts in Seattle, WA.

Q: Can you tell us how you first learned about Photolucida’s Critical Mass, and what motivated you to enter?

PW: I first heard about Critical Mass through the BlueSky-o-Sphere. In 2006, I had an exhibition there and also participated in Photolucida that same year—both experiences were extremely positive. Entering Critical Mass felt like a natural next step, a way to expand my exposure and build on that momentum.

Q: Can you describe how and why you began incorporating books, photographs, and objects into sculptural works? Was there a particular artistic influence or catalyst for this shift?

PW: At heart, I’m a populist who approaches visual art as a form of language. My goal is to create constructs that communicate with the broadest possible audience—beyond just the art-literate—without compromising artistic rigor. Books, photographs, and objects all carry cultural familiarity: books as repositories of knowledge, photography as evidence, objects as tangible forms. Titles, too, are central—they frame the essential meaning of each piece.

If these elements come together successfully, the work embodies what it’s about. The viewer encounters something visually striking yet familiar, feels comfortable enough to “read” it, and begins the process of interpretation. This practice wasn’t a shift away from photography but an expansion. I still make conventional photographs, but sculpture allowed me to make thought visible in a uniquely personal way.

Q: Your process looks very labor-intensive—does the photograph or the object typically come first? Do you draw the theme from the image and then extend that intention with an object, or does it unfold differently?

PW: All of the above. Titles are the only actual literature I use, and I treat them carefully—crafted to be poetic, or at least poetic in tone, so they give the viewer an access point. They represent the essential meaning of a work. All other “reading” happens semiotically, through the interplay of signs, symbols, and imagery.

I keep an ongoing list of titles and phrases. Sometimes I work almost illustratively, creating until the piece looks like the title in question. Other times ideas emerge from anywhere—it’s my job to recognize their significance. Over time, I’ve trained myself to see the world through symbolic metaphor. Titles also serve as a measure of accomplishment: they don’t just describe what you see, but what you feel as you look.

Q: The themes of colonialism and Black community are clearly present in your work. Do individual pieces tell singular stories, or do they function as part of a larger narrative? Do you know the meaning of a sculpture before you begin, or does it emerge as you work?

PW: Both. Each piece tells its own story, but they also contribute to the larger narrative of my life. The more you see, the more diverse and layered that narrative becomes. Meaning can emerge at the start or in the process, but in either case it has to pass the semiotic test—does it hold up visually and symbolically? In the end, art is what it looks like.

Q: How long have you been working in this sculptural way, and did you feel it allowed you to convey more than a two-dimensional photograph could? In what ways?

PW: I began this approach around 2003–04, when I received a residency at the Center for Photography at Woodstock. That time and space allowed me to fully explore this way of seeing. I believe strongly in aligning media and technique with idea and content—there are many ways to do the right thing, but some are more right than others.

One advantage of sculpture is that it occupies space. Unlike a photograph, which can only simulate reality, a three-dimensional object asserts its presence. That tangibility carries a different kind of power and resonance.

Q: When creating this body of work, what were your intentions for the viewer? What impact or response did you hope to elicit?

PW: My primary goal is to catalyze abstract thought—to spark the interpretive process so the viewer actively engages with the work rather than passively observes it.

Q: Do you feel you achieved some of those goals? If so, how?

PW: Yes, and more. In 2023 I presented a major solo exhibition of 40 sculptural works alongside photographs at the Bellevue Arts Museum. The show ran for ten months and became a real-world test of my theories. The audience there was demographically rich, thanks to the tech industry’s global draw, and to my delight, the work resonated across ethnicities, generations, and genders.

People weren’t just responding—they were identifying with the work. I think about what audiences know and how they know it, and when they bring their own life experiences to the metaphors, it produces what I call “unanticipated identifiers.” Viewers arrive at conclusions I could never predict, and that’s when I know the work is doing its job.

Q: How do you feel your work has evolved since you were a Critical Mass Top 50 finalist in 2007?

PW: The work has expanded in scope, sophistication, and form. I now create book sculptures without photos, sculptures that integrate photographs, and stand-alone sculptural pieces. For the sake of continuity, I submitted works in a similar format to those from 2007, but in hindsight, I’d include others as well for context.

Back in 2007, the works were all repurposed hardback novels. Today, the pieces are handmade, much larger—sometimes four times the scale—and more interactive in nature.

Q: Do you feel there is still more for you to explore within this process? Do you continue to feel inspired to make work about the Black experience in this way?

PW: Absolutely. I see this practice much like haiku poetry or blues music—economical forms that nonetheless allow for infinite variation and depth. The structure is simple, but within it lies boundless potential for expression.

Think of Frank Sinatra, B.B. King, Ray Charles, Bonnie Raitt, the Rolling Stones, Howlin’ Wolf, John Coltrane, Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton—you get the idea. Each worked within a tradition, but each found their own voice and kept pushing it further. That’s how I see this work, and why it continues to inspire me.

Ian van Coller 2008

South African photographer Ian van Coller has spent more than three decades navigating the intersections of identity, history, and environment through his lens. From his early portraits of domestic workers in post-Apartheid Johannesburg to his ongoing Naturalists of the Long Now project that bridges art and ecological science, his work consistently grapples with intimacy, power, and the legacies that shape our shared present. Recognized as a Critical Mass Top 50 finalist in 2008, Ian continues to use photography as a way to both witness and question—whether confronting the enduring complexities of race and class in South Africa or translating the slow processes of forest decomposition into images that resonate emotionally and scientifically. In this conversation, he reflects on the challenges of representation, the value of collaboration, and the role of art in expanding how we see both each other and the planet.

Ian van Coller was born in 1970, in Johannesburg, South Africa, and grew up in the country during a time of great political turmoil. These formative years became integral to the subject matter van Coller has pursued throughout his artistic career. His work has addressed complex cultural issues of both the apartheid and post-apartheid eras, especially with regards to cultural identity in the face of globalization, and the economic realities of every day life.

Van Coller received a National Diploma in Photography from Technikon Natal in Durban, and in 1992 he moved to the United States to pursue his studies where he received a BFA from Arizona State University, and an MFA from The University of New Mexico. He currently lives in Bozeman, Montana with his wife, and two dogs, and is a Professor of Photography at Montana State University.

His work has been widely exhibited nationally and internationally and is held in many significant museum collections, including The Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Getty Research Institute, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Library of Congress, and The South African National Gallery. Van Coller’s first monograph, Interior Relations, was published by Charles Lane Press (New York) in 2011. He is a 2018 Guggenheim Fellow, and a Fellow at The Explorers Club.

Van Coller’s current work focuses on environmental issues related to climate change and deep time. These projects have centered on the production of large scale artist books, as well as direct collaborations with paleo-climatologists.

Instagram @ianvancoller

Q: Can you tell us how you first learned about Photolucida’s Critical Mass, and what motivated you to enter?

IVC: It’s been 17 years since I first submitted to CM, so I don’t remember exactly. I believe I first heard about it when I attended the Photolucida Portfolio Reviews right after finishing graduate school in 2005.

Q: In your Critical Mass 2008 Top 50 finalist portrait project of domestic workers within the homes where they are employed, you allowed them to choose their dress and posture. How did those decisions shape or even challenge your own expectations of how they might present themselves?

IVC: I was fortunate to meet Seydou Keïta in Bamako, Mali, in 1998, and his work was a major influence on me. He represented one of the first African photographers making portraits of African identities. At the same time, I was acutely aware of the destructive legacies of colonial photography in Africa, and what it might mean for me—a white South African man—to create formal portraits of Black South African women. It was a tenuous line to walk.

I also spent time with the writings of Okwui Enwezor, who emphasized the “straightforward presentation of the self” and the role of fashion in constructing uniquely African identities. This reinforced the need for the women in my portraits to assert themselves through their own choices. My expectations were more than met: they dressed and posed with great dignity, projecting strength and confidence in their identities.

Q: The project is situated in the complicated space between intimacy and inequality—where employers and domestic workers live in close proximity yet remain divided by race, class, and history. How did you navigate that tension while photographing, and did the process alter your understanding of post-Apartheid relationships?

IVC: This was without a doubt the most difficult project of my 30-year career. As someone who grew up with privilege in South Africa, I constantly asked myself whether I was the right person to make this work. Yet it was also bound up with my own experience growing up in Johannesburg, where the men and women my family employed played significant roles in my life.

The camera, of course, also places the photographer in a position of power, which made the encounters even more complex and intimate. Navigating that tension was deeply personal as well as photographic. At the time, this felt like an untold story—an enduring legacy of Apartheid that I felt compelled to document.

Q: You paired photographic portraiture with oral recordings of the women. How do you see the relationship between voice and image functioning in this project? Do they reinforce one another, or do they reveal contradictions?

IVC: Honestly, I don’t have a strong answer for that. When Charles Lane Press published the project, Sindiwe Magona contributed an introductory essay, but we chose not to include the oral recordings. Collecting oral histories is a skill in itself, and what I had gathered wasn’t strong enough. That’s one reason I value collaboration so highly—others can bring expertise and depth that I cannot.

Q: In what ways do you see this body of work contributing to photographic discourse around Africa and post-colonial identities, both within South Africa and internationally?

IVC: Photographs and stories by Africans are essential in countering the pervasive misconceptions about the continent. Africa is not a country; it is a vast, complex place. Photography has too often flattened it into a monolith of war and starvation. South Africa alone is filled with extraordinary image-makers creating new narratives.

I see my project as just one contribution among many that grapple with post-colonial identities in the wake of Apartheid. Its intimacy—and its focus on domestic labor—make it somewhat controversial, but that tension is part of the conversation I hoped to provoke.

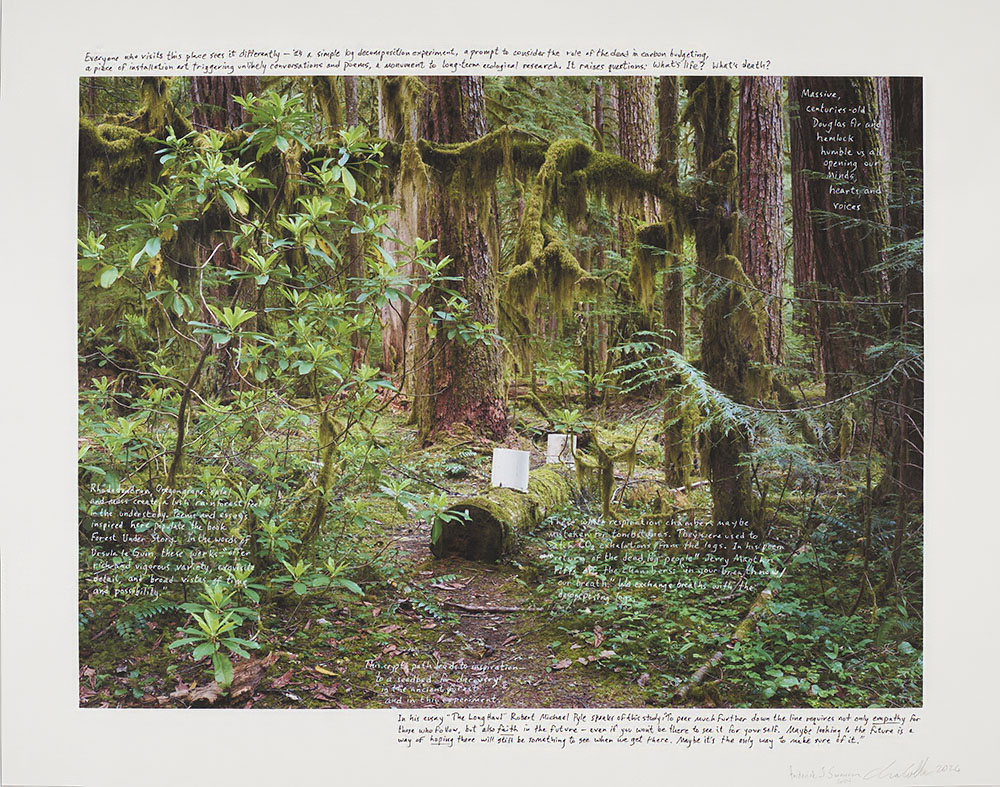

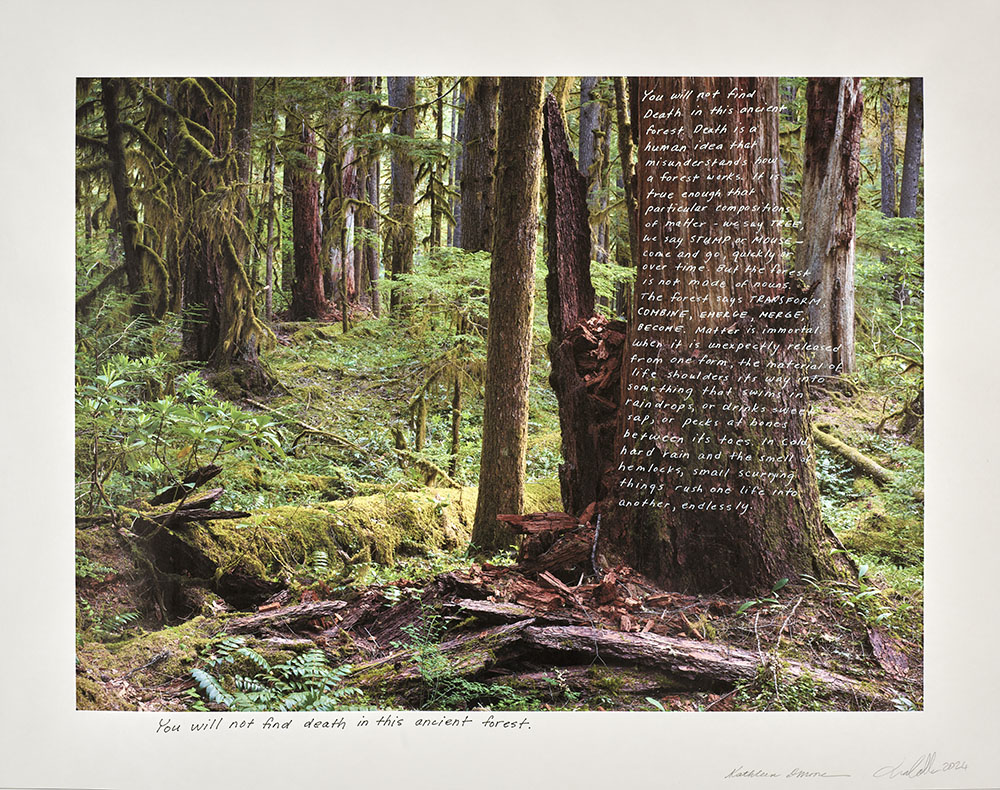

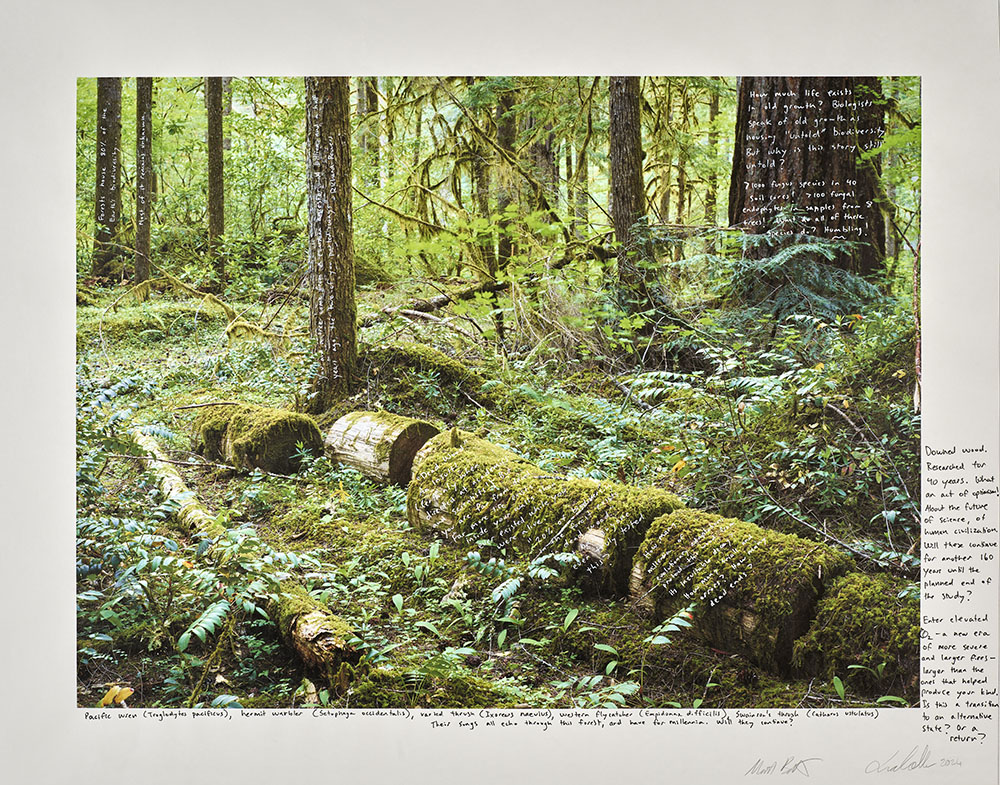

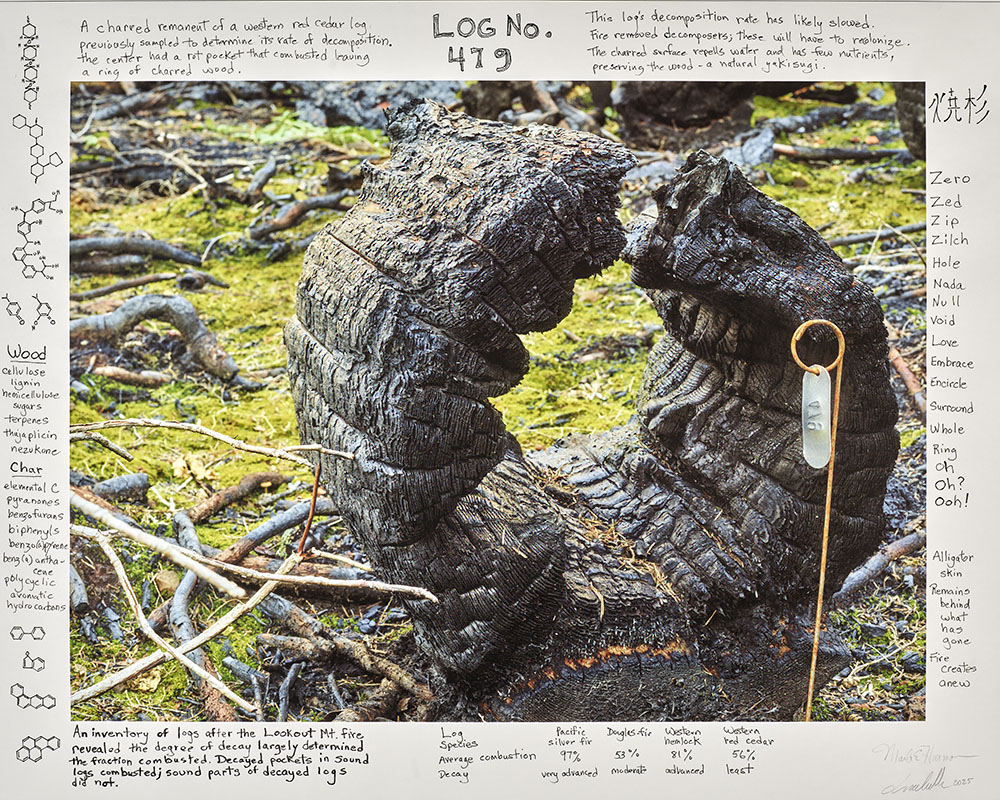

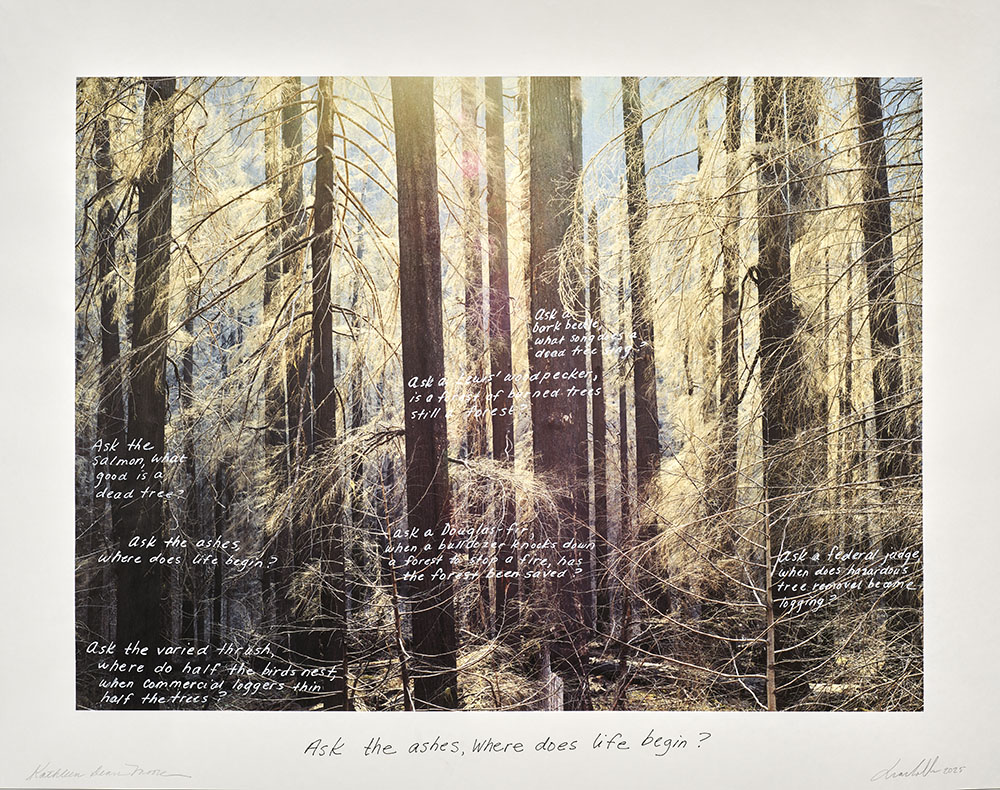

Q: Your more recent work, part of Naturalists of the Long Now, is deeply tied to the scientific study of decomposition and carbon storage. How do you see your role as an artist in translating this long-term ecological research into a visual and emotional experience?

IVC: Since the Victorian era, the arts and sciences have become increasingly siloed. Our educational systems reward narrow specialization, and academic papers on climate change are often impenetrable to the general public. Art can make science accessible and emotionally resonant. It builds empathy and connection.

When I began this work 13 years ago, climate change was rarely covered in mainstream media. Now, entire sections of newspapers are dedicated to it. Artists, I believe, have helped push this awareness by translating scientific urgency into human terms. My goal is to bring beauty, empathy, and understanding to these ecological issues.

Q: The annotations from scientists and writers have become integral to the work. How did these collaborations shape your understanding of the forest and influence your photography?

IVC: This began in 2012, when I collaborated with two artist friends, Todd Anderson and Bruce Crownover, on fast-melting glaciers in Montana. I realized I was seduced by the beauty of those landscapes but lacked deep understanding. Around that time, I read Andrea Wulf’s The Invention of Nature, about Alexander von Humboldt, who articulated the concept of interconnected ecologies. His map of Chimborazo, blending scientific data with artistic vision, became a touchstone for me.

Seeking out scientists transformed my practice. Traveling with them to research sites, listening to their insights, I came to see the forest differently. For example, I learned that a decaying log can contain more living cells than a standing tree because of the multitude of organisms involved. That knowledge shifted my eye—and my camera—toward decay as a site of life and abundance.

Q: You photographed the forest before and after a major burn event. What was it like to return afterward, and how did it affect your perception of time, change, and resilience?

IVC: Photographing climate change can be depressing. But I find hope in beauty, and even the burned landscape had its own sublime allure. Beyond aesthetics, I came to understand fire as an agent of renewal, opening new avenues for research and regeneration.

Fred Swanson, who invited me to residencies at the HJ Andrews Experimental Forest, has written beautifully about this. He described how fire reshaped long-term ecological experiments and opened new questions, even new roles for the humanities in helping us grapple with grief and transformation. That perspective has been vital for me.

Q: This project emphasizes thinking in “long now” terms—hundreds or thousands of years. How do you balance making work that resonates with audiences today while pointing toward such distant futures?

IVC: My friend Eirik Johnson introduced me to the Long Now Foundation and their 10,000-year clock, designed to prompt long-term thinking. I found that concept inspiring and began to think of my own photographs—as records of glaciers, forests, and earth systems—as Long Now clocks.

Whether audiences connect with that time scale, I’m not sure. But for me, it’s an essential way to frame the work, to push beyond the short-term horizons we’re used to.

Q: Finally, did being recognized as a Critical Mass Top 50 artist open opportunities for you—either immediately or over the longer term?

IVC: Yes, absolutely. I’ve continued to submit to CM over the years because it remains an accessible way to share new work widely. I’ve had projects published and exhibited as a direct result of people seeing them through CM—everything from features in Osmos Magazine and MIT Technology Review to two solo exhibitions at Blue Sky Gallery in Portland. It’s been a consistent and valuable platform.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Shane Hallinan: The 2025 Salon Jane Award WinnerFebruary 12th, 2026

-

Greg Constantine: 7 Doors: An American GulagJanuary 17th, 2026

-

Yorgos Efthymiadis: The James and Audrey Foster Prize 2025 WinnerJanuary 2nd, 2026

-

Arnold Newman Prize: C. Rose Smith: Scenes of Self: Redressing PatriarchyNovember 24th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Cathy Cone (2023) and Takeisha Jefferson (2024)October 1st, 2025