The Female Gaze: Jane Szabo – Recent Work

Los Angeles-based conceptual artist Jane Szabo merges a love for fabrication and materials with visceral photographic images. The core of her work revolves around ideas; she uses photography as a storytelling medium, where the narratives are deeply rooted in personal experiences. Her images can be seen as a diary that records details of life over time, or a series of self-portraits, even when she is not physically present in them.

Szabo’s work has been exhibited in solo shows at Danforth Art Museum, Griffin Museum of Photography, Forsberg Gallery at Lower Columbia College, Huntley Gallery/Cal Poly Pomona, Koslov Larsen Gallery in Houston, TX, John Wayne Orange County Airport, Museum of Art & History in Lancaster, CA, Foto Museum Casa Coyoacán in Mexico City, Orange County Center for Contemporary Art, Yuma Fine Art Center in Arizona, and Los Angeles Center for Digital Art.

Szabo’s art is in the permanent collections of Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Museum of Art & History, Arte al Limite Santiago, Chile, Centro de Arte Faro Cabo Mayor in Santander, Spain and in private collections throughout the U.S. and Europe. She holds an MFA from Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, CA.

©Jane Szabo – I Am Not Giving Up (digital pigment print, 2022), from the series I Am. I Am Here. I Matter.

I met Jane Szabo on Facebook about ten years ago. I’m sure I went out of my way to interact with her in one group or another, because she had made work I wished I had made. Eventually we attended several of the same portfolio reviews (pre-pandemic, when they were always in-person events) and became friends. After I started writing for Blue Mitchell at OneTwelve in 2020, I approached Szabo about featuring her portfolio because it gave me an opportunity to write about the work of hers that I loved so much, entitled Sense of Self. In 2023, writing The Female Gaze at FRAMES Magazine, I covered work from her Somewhere Else series—because that work made me feel as if she could read my mind.

Due of this history of writing about Szabo’s work, I’ve chosen to do this edition of the The Female Gaze a bit differently. Rather than re-covering series I’ve touched on elsewhere, I decided to focus only on the last three projects Szabo has done.

One of the things I love about Szabo’s work is her use of hand-made, non-photographic objects as part of her work. Another is how Szabo changes her work to fit the statement and concept she is working with. There is always something new happening with her work.

Her project I Am, I Am Here, I Matter turns inward, focusing on life’s fleeting details. Through photography, video, and sound, Szabo captures shimmering water, ripening fruit, and moments of profound stillness. The series is both meditation and proclamation: an assertion of presence, visibility, and worth.

In Damaged, she explores the tension between sorrow and resilience. Using pigment transfer on watercolor paper, she creates prints with jagged edges and textured surfaces that echo the scars born of human actions on our planet. They acknowledge hardship and loss while also pointing us toward solace—the warmth of sunlight, the whisper of wind but also to the beauty of the landscape inside ourselves. They remind us that though our world may break, it can also mend, and that humans do, as well.

With The Anthropocene Epoch, Szabo broadens her gaze. Fragile paper globes, covered in maps and placed in forests, meadows, and tidal zones, are left to weather sun, tide, and rain. These delicate interventions come from lived experience with climate change. They stand as metaphors for our planet’s precarity—and its potential for renewal.

Szabo’s photography invites us to consider the delicate balance between life’s harsher realities and the threads of hope woven through them. Her images lean into fragility yet celebrate the strength we draw from nature, memory, and the quiet rituals that carry us forward. Working with handmade objects, textures, and symbolic gestures, Szabo gives each piece a tactile presence that deepens its visual narrative.

© Jane Szabo – Fallen Pears (digital pigment print, 2022), from the series I am. I am Here. I Matter.

DNJ: I’m looking at your series, I am. I am Here. I Matter. Your experience with the pandemic led you to ultimately communing with nature in a way that feels similar to the way the ancient Hawaiians treated the land, the air, and the sea—which is maybe something I am projecting onto this, since I live in Hawai’i. What brought you to this way of thinking?

JS: My retreat into nature actually began right at the start of the pandemic—it was already part of my daily life. I live within the boundary of a national forest, so stepping into the woods is as simple as walking out my front door. When we were confined to our homes, the forest became a vital refuge—a safe space where I could move freely and reconnect with the world beyond walls.

The turning point came after visiting several UNESCO World Heritage Sites, including the Caves of Altamira, Las Monedas, and El Pendo, to see the Paleolithic cave art of northern Spain. Standing inside these caverns—once homes and gathering places for Neanderthals and early humans—I was struck by the immense stretch of time the Earth has been inhabited, and how much of the planet’s damage has occurred only in the relatively short period since the Industrial Age.

I spent much of my residency enjoying the solitude, walking through farmlands and along the coast. I became acutely aware of my presence on the land, my connection to humans over the ages, and how human activities—farming, cattle raising, development—have shaped and scarred the land. That awareness fed into my work, as I began to ask “How can we continue to exist on this planet while minimizing our impact? Can we?”

©Jane Szabo, I am, I am Here, I Matter (digital pigment print, 2022), from the series I Am. I Am Here. I Matter.

DNJ: After the pandemic, you did a residency at SM Pro NAT Art Residence in Cantabria, Spain, that you’ve described in your writings as a “turning point.” What did being immersed in that landscape and culture unlock for you that isolation alone could not?

JS: By the time I arrived in Spain, long daily hikes had become a grounding ritual, something I relied on to maintain balance and clarity. The urge to move, to “take a hike,” became almost compulsive—but in the best possible way. It was a form of communion, a practice that deepened my relationship with the land and my own state of being.

DNJ: Why was it vital for you to create I am… as a multi-media installation, rather than strictly photographic images? (Readers: you can see the video here.)

JS: The work began as a walking meditation—an immersive state of awareness that engaged all the senses: the wind on my skin, the sound of the surf, the smells of freshly cut grass and nearby farm animals.

Expanding the project to include video and an audio recording, based on writing I did on site, allowed me to convey that experience more fully. That said, to date, I’ve had the opportunity to exhibit the work strictly as photographs rather than an installation. They hold their own as standalone works.

©Jane Szabo – Can I Stop Running Now? (digital pigment print, 2022), from the series I am. I am Here. I Matter.

DNJ: In the artist’s statement for this work, you describe seeking your voice not as a human, but as the “pulse of the air” or “the flow of the water.” Can you expand on what it means to dissolve the boundary between self and nature?

JS: Spending extended time alone in a foreign country gave me space to honestly reflect on my existence—especially my hopes and fears around climate change and our collective survival. Those long, contemplative walks became a way to disconnect from devices, noise, and the constant pressure of urban life. I slowed down. I breathed.

I walked in the rain without worrying about getting wet, simply allowing myself to feel the sensation of water on my skin. I found comfort in solitude—chatting with cows and sheep along the path, pausing to watch a slug cross the road, sitting quietly as the tide rolled in.

Over time, I stopped feeling like a visitor in the landscape and began to merge with it. I was no longer just observing; I was part of the rhythm. Each evening I found myself breathing a little deeper, soothed by the soft, familiar chime of cowbells from nearby fields as I fell asleep.

DNJ: What do you hope viewers will feel or experience when they engage with this installation? If viewers walk away with one changed perspective from this project, what would you like it to be?

JS: The vision for the complete installation was to create an immersive experience by combining photography with video and audio—to invite viewers to slow down and truly enter the landscape. I wanted them to hear the wind, see the grasses shift in the breeze, notice the subtle changes in light and movement, and hear my reflections recorded on site.

My hope is that people leave feeling just a little different—more attuned to the natural world, more willing to notice the quiet details that surround them every day. If there’s one shift I’d like to inspire, it’s a deeper sense of connection and care. We need more people to truly see the fragile ecosystems that sustain us, because without that awareness, we can’t hope to protect them.

© Jane Szabo – Northward (#2 of 5 unique, hand-printed limited edition pigment transfer prints, 2021), from the series Damaged

DNJ: Damaged followed I Am. I Am Here. I Matter. This series balances darkness and light, hardship and beauty, fragility and resilience. You describe Damaged as both an escape into the forest and an encounter with our own marred edges. How do these two seemingly opposite impulses coexist in the work?

JS: The title “Damaged” refers not just to emotional or ecological distress, but also to the physical surface of the work itself. The photographic prints are intentionally imperfect—with blurred images and smeared edges, to evoke a sense of vulnerability and erosion. These gestures reflect both the degradation of the environment and the inner damage we all carry, especially in the aftermath of collective trauma like the pandemic.

At the same time, the forest—where much of the imagery was made—served as a refuge. It was a place of quiet, a space where I could breathe deeply and begin to process everything that felt fractured. The physical damage to the images contrasts with the healing nature of the subject matter: light filtering through trees, open skies, the reflections and ripples on the water.

So, the work holds both impulses at once: the need to withdraw and repair, and the acknowledgment of harm—personal, environmental, and societal. The materials and surface treatment of the images make that duality visible. They don’t hide the wounds; they hold them alongside the beauty.

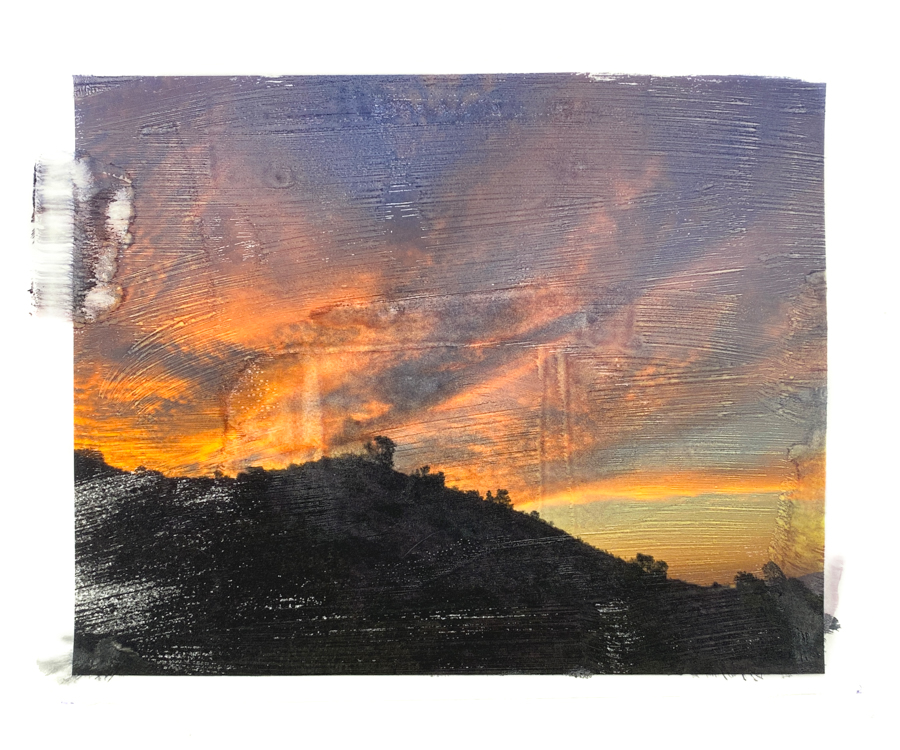

©Jane Szabo – Little Round Top (#2 of 5 unique, hand-printed limited edition pigment transfer prints, ), from the series Damaged

DNJ: Nature plays a central role, described as a place of solace and even transformation. What is it about the forest, specifically, that allows that alchemy to happen in the Damaged work?

JS: I know some people describe forests as intimidating or even claustrophobic, but I’ve always experienced them the opposite way. For me, being beneath towering firs and other majestic trees feels like a kind of embrace—expansive, grounding, and deeply comforting.

I lived for a time in the Seattle area and have returned often to visit family, so the forest has always felt like a homecoming. There’s something about being in the woods that reconnects me to my roots—both literally, through the landscape, and emotionally, through memory and family.

The forest offers a quiet that allows transformation to take place. It doesn’t demand anything. It just holds space—for reflection, for presence, for healing. That’s where the alchemy happens—in the stillness, the repetition of walking, the sensory immersion. It reminds me who I am beneath all the noise.

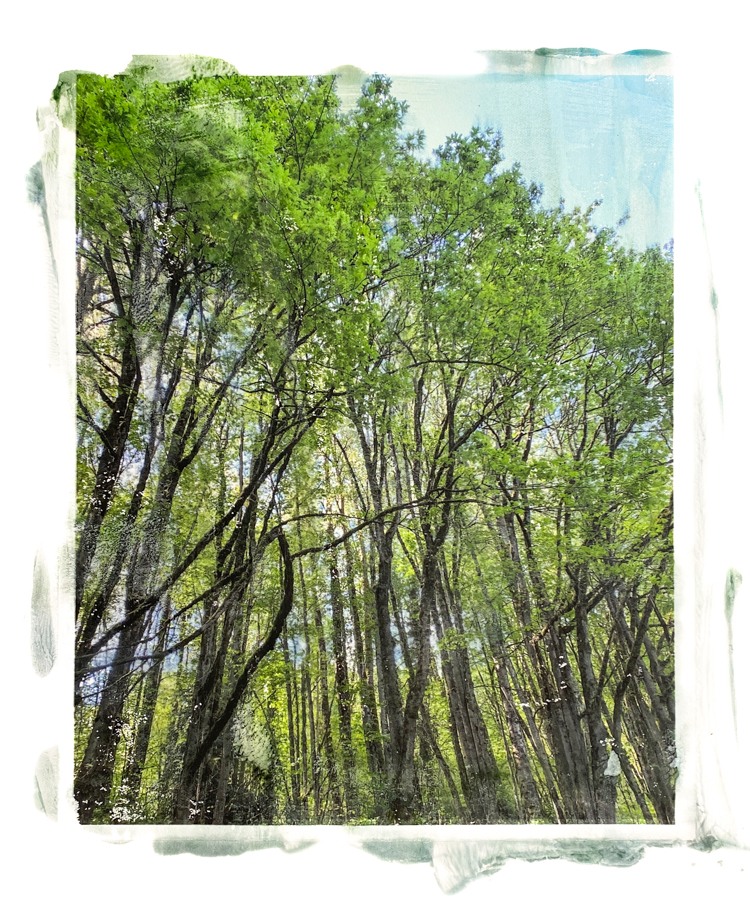

©Jane Szabo – Chorus of Trees (#1 of 5 unique, hand-printed limited edition pigment transfer prints, 2021), from the series Damaged

DNJ: You call a walk in the forest a “spiritual experience.” Do you see Damaged as a kind of ritual, or even an act of healing?

JS: Absolutely. Being in nature is seriously healing for me—it’s where I can finally breathe a little deeper and feel the weight begin to lift. The forest becomes a place of quiet ritual, where I witness the shifting seasons, listen to the birds’ conversations overhead, and observe the slow transformation of soil and rock. Even minute details—a fallen leaf, the arc of a branch, the hush after rain—root me in the present moment, in the vast continuity of the natural world.

That awareness is humbling. It reminds me that my time here is just a blink in the geologic timeline. And yet, within that blink, we’ve inflicted enormous damage.

©Jane Szabo – The Tempest of Emotions (#1 of 5 unique, hand-printed limited edition pigment transfer prints, 2022), from the series Damaged

Living near the area that was devastated by the Station Fire (160,000 acres of National Forest burned in 2009), and more recently the Eaton Fire (more than 9000 homes and businesses destroyed in January 2025), I’ve walked through landscapes that were reduced to white ash—moonscapes stripped of life. But I’ve also watched those places recover over time—native grasses, sages, lupines, and oaks returned—slowly, quietly, persistently.

Sixteen years after the Station Fire, signs of the fire are faint, though still present if you know how to look. That regeneration gives me hope. Damaged is very much tied to that idea: that healing is possible, but it takes time, attention, and a willingness to change. It’s both a personal and ecological act—an invitation to reflect, to reconnect, and to reconsider how we move through the world.

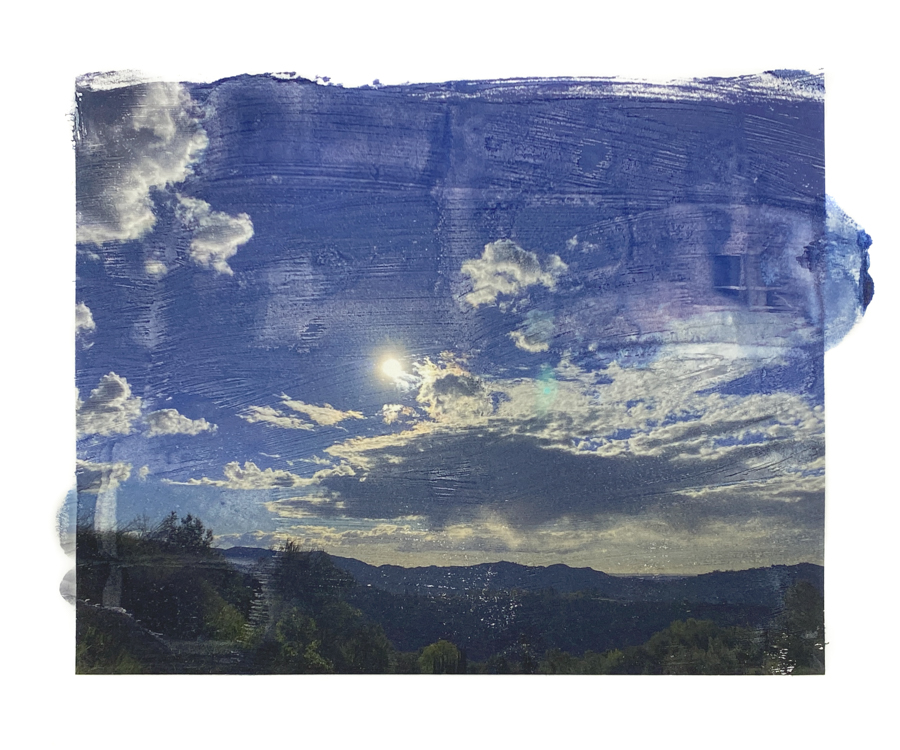

©Jane Szabo – Southern Night (#1 of 5, unique, hand-printed limited edition pigment transfer prints, 2022), from the series Damaged

DNJ: When viewers encounter Damaged, what do you hope they recognize in themselves?

JS: That’s a challenging question, because I don’t necessarily expect viewers to find something specific within themselves immediately. Instead, I hope the work opens a doorway to something beyond the self—a heightened awareness of the beauty and fragility of the natural world, alongside the urgent reality of the damage we’re causing.

At the same time, I hope that this awareness sparks reflection. Perhaps viewers will recognize their own place within this fragile ecosystem—how our choices and actions are intertwined with the health of the planet. I want the work to gently invite people to consider their relationship to nature—not as distant observers, but as connected participants.

Ultimately, if “Damaged” helps someone pause and feel a more profound sense of care or responsibility, even just for a moment, then I believe it has succeeded. It’s less about demanding immediate answers and more about planting a seed of recognition—an opening toward empathy, connection, and hope.

©Jane Szabo – Suffocated by Prairie Grass (digital pigment print, 2025), from the series The Anthropocene Epoch

DNJ: Let’s talk about The Anthropocene Epoch series, which is currently in a work-in-progress. As a resident of Altadena, the Eaton Fire deeply affected you and your community. How did living through that climate disaster shift your perspective on environmental grief and responsibility?

JS: I’ve long been aware of the risks climate change poses—catastrophic fires like the one we faced in Altadena, increasingly powerful storms, flooding, heat waves, and the financial burdens that come with adapting to these new realities. Even though I was actively preparing for these threats, nothing could have fully prepared me for the experience of seeing half of our town burn and facing long-term displacement.

Living through that disaster deepened my sense of environmental grief but also strengthened my resolve to act. It’s pushed me to embody the change I want to see, both in my daily life and through my creative work. My goal isn’t to produce instructional or didactic pieces, but rather to create work that is poetic and inspirational—something that moves people emotionally and opens space for reflection and hope.

©Jane Szabo – Perilous Balance (digital pigment print, 2025), from the series The Anthropocene Epoch

DNJ: The papier-mâché globes are central to your interventions. How did you arrive at this form, and what do they allow you to express that photographs alone could not?

JS: I have incorporated maps into my work for many years across diverse projects, so using a globe felt like a natural extension of this exploration. However, I found traditional globes too rigid and precise for the ideas I wanted to convey.

By creating handmade papier-mâché globes, I introduced distortion and imperfection—not only in the shapes of the continents but in the very form itself. This looseness shifts the narrative away from a fixed, factual world map toward something more symbolic and open to interpretation. These globes embody the disarray, fragility, and collapse I perceive in the world today, capturing its instability and uncertainty.

I’ve used these objects both as elements within staged photographs and exhibited them as sculptural pieces. Presenting them as sculptures invites viewers to fully engage with their physicality—leaning in close to observe the warped roadways, uneven surfaces, and irregular forms. This tactile experience reveals the vulnerability and impermanence of the world.

©Jane Szabo – Creature of the Anthropocene (digital pigment print, 2025), from the series, The Anthropocene Epoch

DNJ: Collaging the globes with maps—roads, waterways, and green spaces—creates a layered symbolism. How do these cartographic fragments function in the narrative of the work?

JS: Maps are traditionally tools for navigation, helping us find our place in the world. But the globes I create resist that clarity. Instead of offering guidance, they embody chaos and fragmentation.

The collaged maps—with their disrupted roadways, blocked rivers, and fragmented green spaces—reflect the haphazard, often destructive ways we’ve altered the Earth. These cartographic fragments symbolize how human development frequently ignores the natural ecosystems it impacts, imposing order that ultimately creates imbalance and disarray.

©Jane Szabo – Returning to the Source (digital pigment print, 2025), from the series The Anthropocene Epoch

DNJ: The interventions are intentionally impermanent, vulnerable to wind, rain, and tide. How important is ephemerality to the meaning of the project?

JS: The interventions I create are designed to be photographed—they’re not meant to remain in place over time. I’m careful to leave no trace of my presence in the landscape, but I also want the natural elements—wind, rain, tide—to become active participants in the work.

This vulnerability and impermanence convey a powerful sense of fragility and risk. Will the tide wash it away? Will the wild grasses reclaim the space? Will the wind topple the stack of globes? These questions introduce tension and life into the images, allowing the landscape itself to continue the narrative long after the physical objects are gone.

©Jane Szabo – Recovering Waterways (digital pigment print, 2025), from the series The Anthropocene Epoch

DNJ: The project holds both grief and hope. How do you navigate that balance in your creative process?

JS: This balance stems from my experience witnessing fires sweep through our forests multiple times. The devastation is heartbreaking, but it’s followed by recovery and regrowth. I often find myself deeply troubled by the damage humans are inflicting on the planet—and yes, I do sometimes fall into despair.

Yet, I also find joy and hope when I escape into nature. Creating work in the landscape becomes a form of personal healing, a way to process the climate-driven trauma I’m experiencing as a displaced resident of Altadena. Through this creative process, I hold space for both the grief of loss and the possibility of renewal.

©Jane Szabo – Line of Uncertainty (digital pigment print, 2025), from the series The Anthropocene Epoch

DNJ: What is coming up on the horizon for you?

JS: The past nine months since the Eaton Fire tore through Altadena have been incredibly challenging. While our home survived, we’ve been displaced due to smoke damage and frustrating delays from our insurance provider. Normally, I consider myself resilient, but this sense of helplessness in trying to move the recovery process forward has been overwhelming.

In a moment of impulsive desperation, I applied to an artist residency in Sweden — and I’m honored to have been selected. This fall, I’ll be heading to Björkö Konstnod (BKN) to take part in the Lucid Dreaming Program, a four-week residency where the forest meets the sea. While BKN typically hosts a diverse group of international artists, this particular residency was proposed by fellow Altadena artist Susannah Mills as The Los Angeles Wildfire Residency.

I’ll be joining 11 other artists — painters, photographers, writers, dancers — all of us impacted by fire, to spend time in creative healing and communion with nature on a Swedish island. I’m deeply grateful for the opportunity to step away from the stress of post-fire life and curious to see how this experience will shape my work moving forward.

©Jane Szabo – Rewilding the Land (digital pigment print, 2025), from the series The Anthropocene Epoch

Thank you ever so much, Jane, for taking the time to speak with me about these works. I’ve enjoyed learning about these projects, and I am sure our readers will as well.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The Female Gaze: Anne Berry – Ode to the Blue HorsesNovember 13th, 2025

-

The Female Gaze: Lara Gilks – Just Outside the FrameOctober 23rd, 2025

-

The Female Gaze: Jane Szabo – Recent WorkSeptember 21st, 2025

-

The Female Gaze: Karen Klinedinst – Nature, Loss, and NurtureAugust 23rd, 2025

-

The Female Gaze: Judith Nangala Crispin – A Committed PracticeJuly 31st, 2025