Photography Educator: Dana Fritz

©Dana Fritz, Betula papyrifera: an elegy, (2022, hand bound artist book,) takes the form of a scroll in which photographs of decaying, hollow birch trees are unfurled by a viewer. Paper birch trees have relatively short life spans but decompose slowly on the forest floor. Long after the inner wood has been recycled by insects and fungi, their water-resistant bark skins remain as hollow horizontal forms, vestiges of a bygone climate.

Photography Educator is a monthly series on Lenscratch. Once a month, we celebrate a dedicated photography teacher by sharing their insights, strategies and excellence in inspiring students of all ages. These educators play a transformative role in student development, acting as mentors and guides who create environments where students feel valued and supported, fostering confidence and resilience.

It gives me great pleasure to feature photographer, book artist and educator Dana Fritz and a few of her students this month. Dana’s dedication to her own photographic practice is readily apparent in the deeply researched and visually sophisticated books she shared for this article. As a Professor of Art in the School of Art, Art History & Design at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln School of Art, her teaching approach centers on immersive creative exploration, encouraging critical reflection and the growth of independent artistic voices within a supportive community. Her students’ work is conceptually strong, diverse and interesting, a testament to Dana’s commitment as an educator. Dana’s thoughtful responses to my questions in this interview make clear that she is deeply invested in supporting her students, going beyond expectations to help them cultivate a rich and long lasting artistic practice.

This article starts with a sampling of Dana’s work in book form.

Engaging ideas about climate change, environmental history, and ecology, I work to reveal the ways we shape and know the land in prints and books. My practice involves remote library and archival research as well as on site ground truthing through observation and photography. Black and white images expose human and non-human patterns while the page spreads, sequences, and texts of books offer pathways to interpretation and interrogation of our relationship to place.

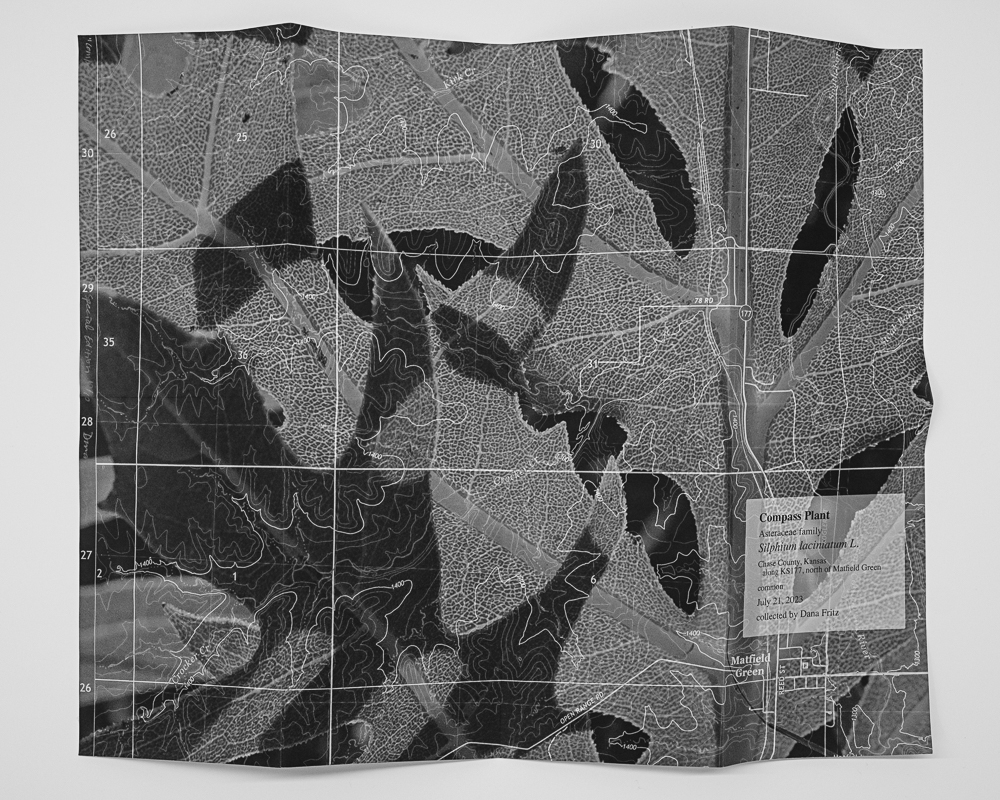

Compass Plant/Map, (2023, artist book,) is inspired by Silphium laciniatum’s flat vertical map-like leaves that point north and south but face east and west. Photographs of their flat, planar leaves are layered with a topographic map of the collection site with topographic lines that resemble the shape of compass plant leaves. The outside includes text prepared as if it were an herbarium specimen, including the collector and the site of collection.

ES: How and why did you get into teaching? Did you always want to be a teacher?

DF: Yes, I always wanted to be a teacher (and a student.) Even as a child I loved school and loved learning. In fact, I never stopped going to school. I went from preschool to graduate school to adjunct teaching to my job at University of Nebraska without a break. I don’t necessarily recommend this for everyone, but I couldn’t imagine myself doing anything else.

ES: What keeps you engaged as an educator?

DF: This week I am preparing for my 28th year teaching at University of Nebraska-Lincoln, my first fulltime, tenure-track teaching job. I was hired to teach in an interdisciplinary foundations program where I mostly taught drawing, but moved to photography in fall 2011, so I have only been teaching photography at UNL for the last 14 years. This big change has kept me on my toes, along with teaching a study abroad course in Japan for 10 years and regularly teaching a Capstone course for graduating seniors of all studio areas. Teaching in these various contexts has keep me engaged and constantly reconsidering how I can make course experiences more meaningful and empowering for students. Since 2012, I have worked closely with graduate students as instructor, advisor, and mentor. This experience has taught me so much and I am grateful for the structure of our program that fosters this kind of exchange.

My basic teaching philosophy evolved over many years with the luxury of teaching relatively small undergraduate classes and working mostly independently with graduate students. In a studio art course with an average enrollment of under 16 that meets 5-6 hours per week, I get to know each student as an individual. The better I know them, the more I can help them. In these ideal learning settings, I recognize my students’ faces, voices, and developing visual language. I learn their individual strengths and challenges and work with them to identify and achieve goals based on the stated learning objectives and sometimes outside of them. This way of teaching demands a great deal of creativity on my part because each student may need a different approach or example to inspire or explain. Each interaction with a student draws on creative problem solving that is analogous to my own process as an artist. I also learn from each student how better to help them and others. This is an exceptionally rewarding teaching situation for me and many students stay in touch after graduating to update me on their accomplishments.

ES: Did you have an influential photography mentor or teacher? What was their biggest impact on you?

DF: I have had many influential teachers of all kinds over the years, but I learned some key things that shaped my work from three people. Patrick Clancy, a photography instructor at Kansas City Art Institute taught me that I could be motivated by and make art informed by ideas outside of myself and photography, pushing the bounds of traditional prints. Wendy Geller, his colleague and my video teacher at KCAI, taught me to take my work seriously and seek challenges, new information, and new experiences to feed it. Mark Klett taught me about understanding place in all its dimensions when I had the good fortune to work with him and others on a grant project about water in the Phoenix area (c. 1992-1995!) While I was never technically his student during my grad program at Arizona State University, he was certainly a mentor through this project. Each of these people modeled the life of an artist and professor when I was just learning what that could mean.

ES: What are some of the assignments that you give your students?

DF: One of my teaching goals in Intermediate and Advanced Photography where students work on self-directed projects is to foster student understanding of their work in multiple dimensions so they will be able to talk about it, write about it, and develop it. To support this, I assign an interview by a classmate where a student is asked to speak freely and without fear of not knowing all the answers right away. The questions span the student’s visual language, subject, content, process, inspiration/input, and intentions for the work. A related assignment is “Show and Tell: Research and Inspiration” where students share several times throughout the semester what they are looking at, reading, watching, etc. and how it supports their work. I require library visits so many of the items shared are photobooks from UNL’s large collection, but students also share artists websites, interviews, technical information, or readings from other disciplines.

In the Beginning Darkroom class, I have been increasingly concerned with the ever-higher cost of paper and film as well as the environmental cost of silver-based photography. In an effort to address both concerns, I developed a collage assignment in which students must use only printed materials that were deemed unfit for critiques: test strips, test prints, bad prints, etc. This assignment is the last of the semester in which they have saved everything they printed and incorporate it into a large piece or series that enables them to make work at a much larger scale than the typical 8×10 prints in a beginning course. It also diverts silver-based paper from the landfill.

One of my favorite courses to teach is an Environment/Landscape/Photography seminar, a mixed undergraduate and graduate course in which students read texts, lead discussions and presentations, and propose exhibitions of photography from the Sheldon Museum of Art’s collection. Over the last decade, I have taught this course four times and each time the Sheldon curatorial staff selected one or two student-curated exhibitions to install at the museum. Until taking this class, many students dismissed landscape photography as a genre that was mostly concerned with beauty. Through looking critically at landscape representations in photography, we can discuss food and energy systems, land ownership, recreation, conservation, and the conflict that arises when people with differing philosophies set sights on the same land. Students comment on how much they valued and were challenged by the readings, discussions, and experience of curating an exhibition for the museum. Some have even gone on to include curatorial practice in their varied professional work.

ES: How do you integrate your experience and success as an artist into your teaching practice?

DF: I share my successes AND failures/rejections with students. I share that I spend more time writing grants, proposals, etc. and on email correspondence than on actually making photographs and that my acceptance rate is not that high. I tell students that each rejection should inspire another application or proposal rather than a pitiful sulk. These admissions are revelatory, not only to my photography students, but to the graduating Capstone students in studio art I teach every semester and who assumed that their faculty are naturally and consistently successful. I am especially excited to share Natalie Krick’s new book published by Composit Press, We are Sorry that You Applied this Year. Natalie’s rejection letters that were modified by deleting large amounts of text have me laughing out loud and feeling seen while commiserating.

ES: What has been your biggest sacrifice?

DF: One of my biggest sacrifices of my own studio time was an investment in my students: when I moved from teaching foundations to photography 14 years ago, I spent two summers and countless hours during the academic year overhauling photo lab and curriculum. I supervised and partially conducted the renovation of languishing facilities to support the curricular changes that include a greater emphasis on and integration with digital technology as well as reinvestments in traditional processes.

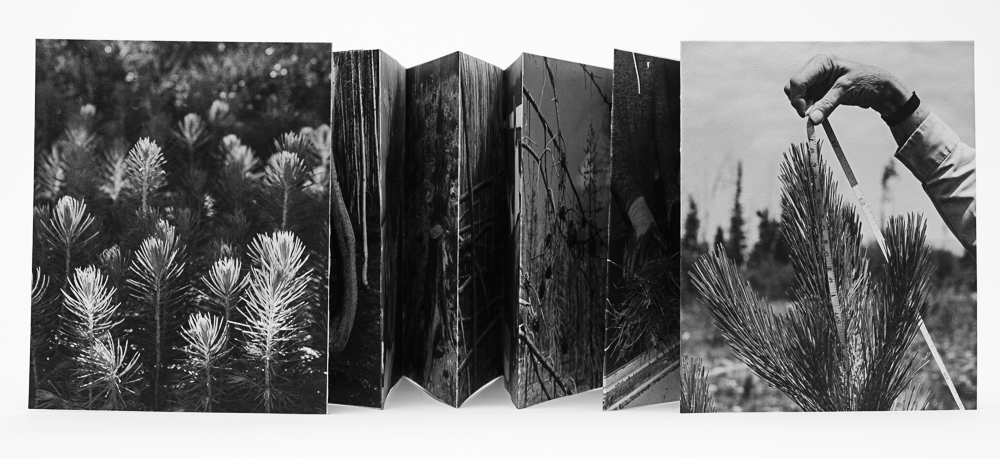

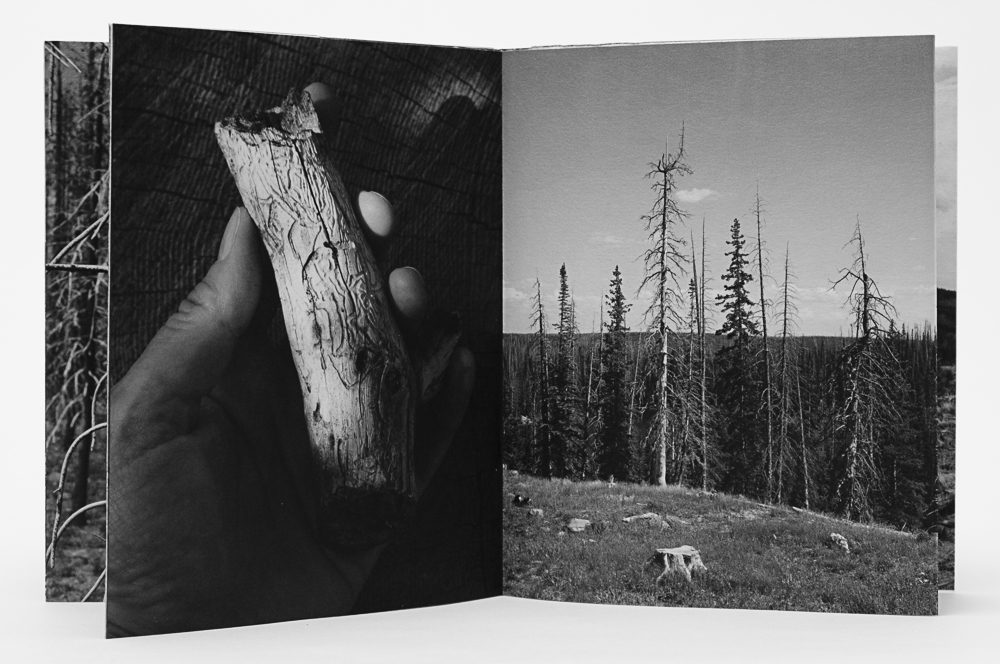

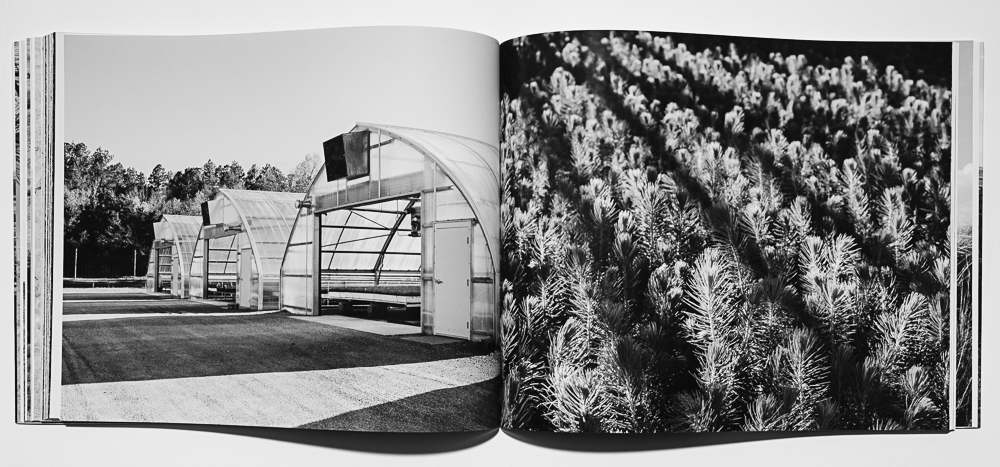

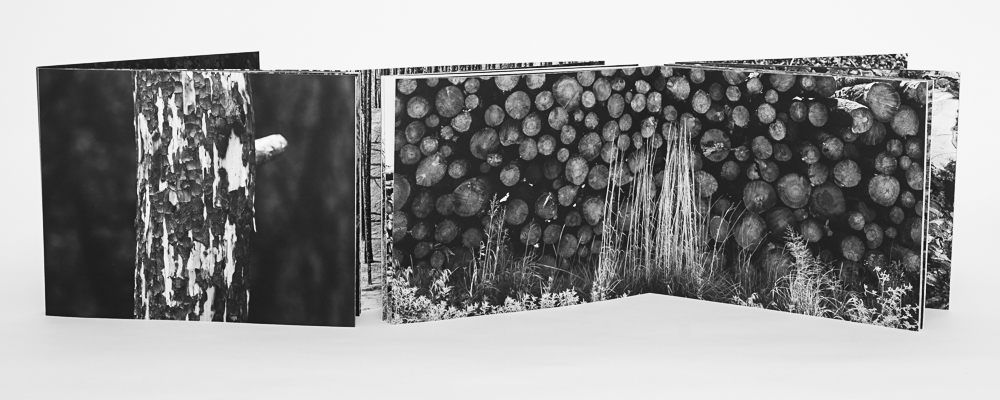

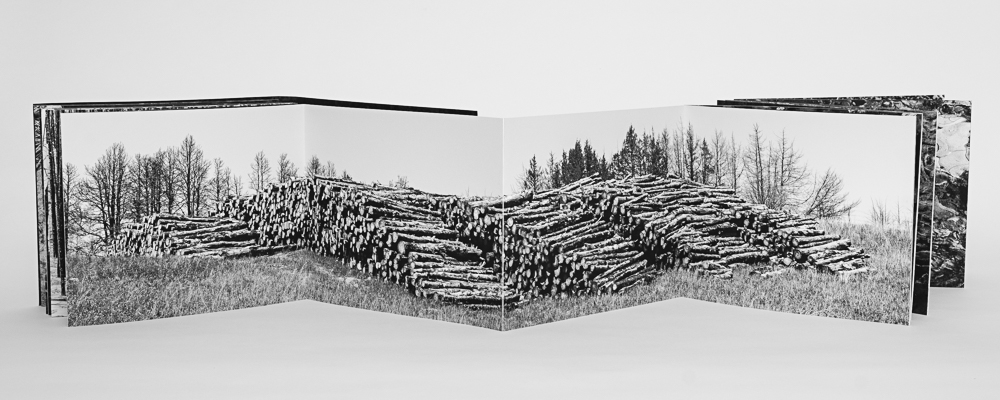

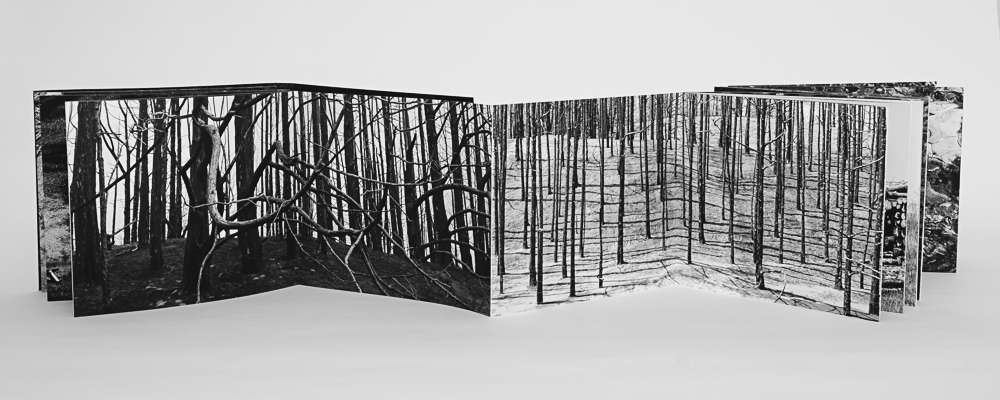

Re: forest, (2022, hand bound artist book,) follows the circular path from Nebraska’s Bessey Nursery to where seedlings are planted in Pike, Roosevelt, and Medicine Bow National Forest areas in Colorado and Wyoming that have suffered catastrophic wildfire and beetle infestations. The photographs loop from the nursery to the forests and back, reminding us that we are inextricably part of this process and that our work to maintain forests is ongoing.

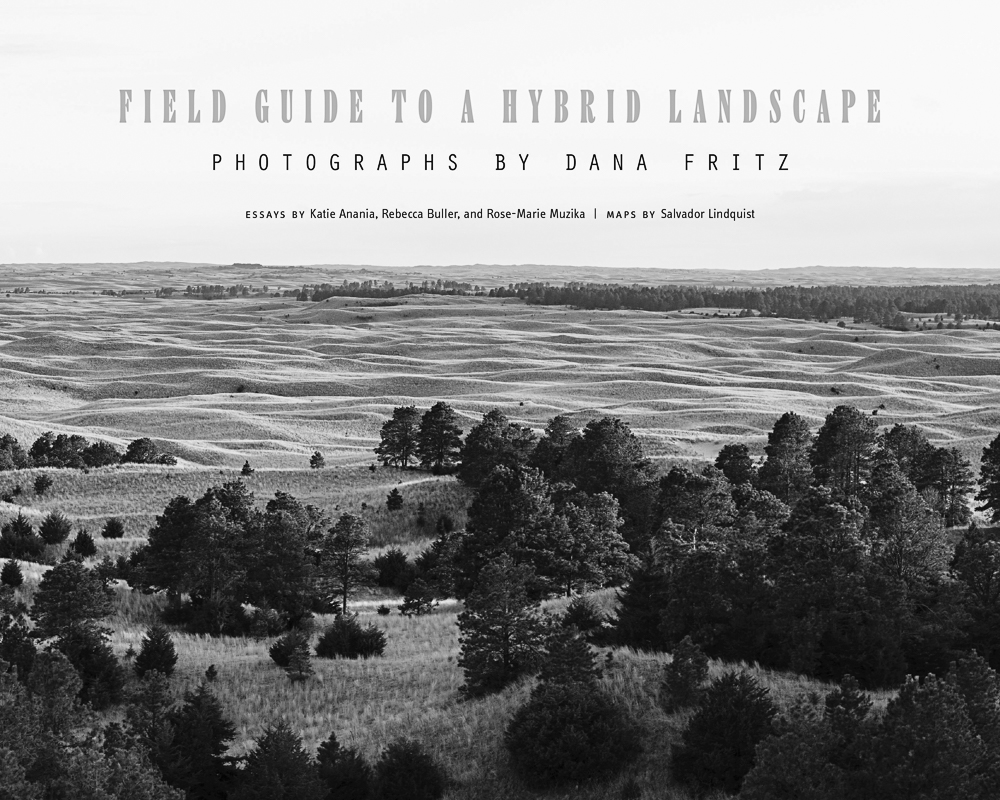

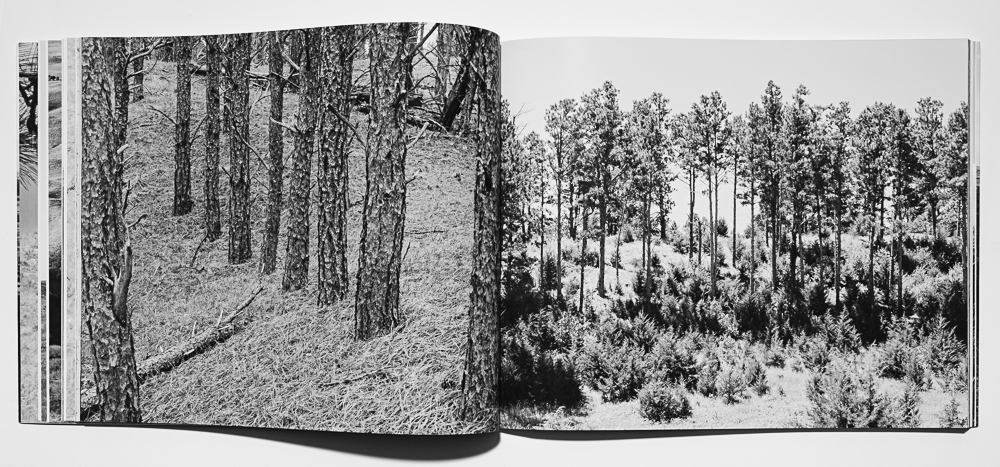

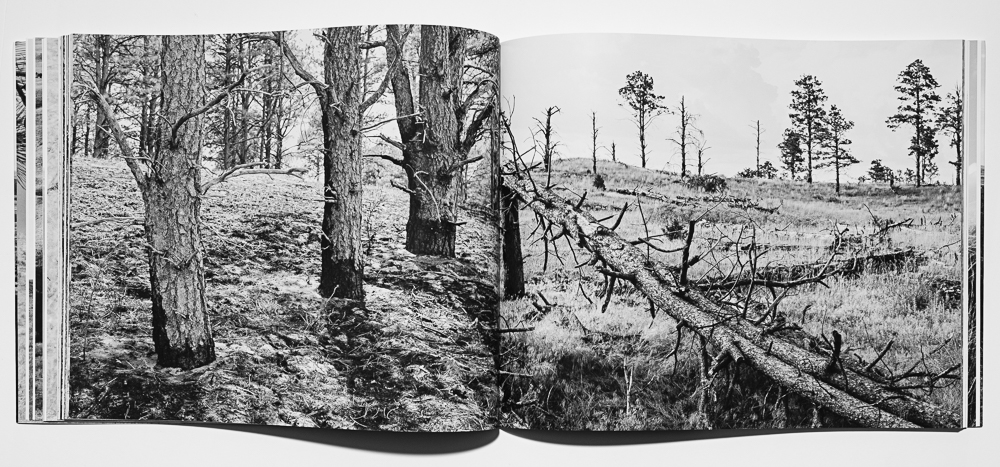

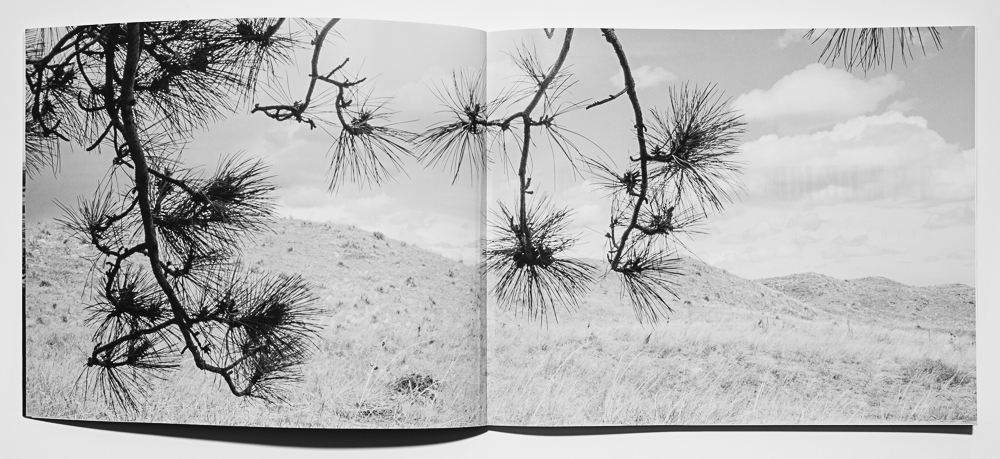

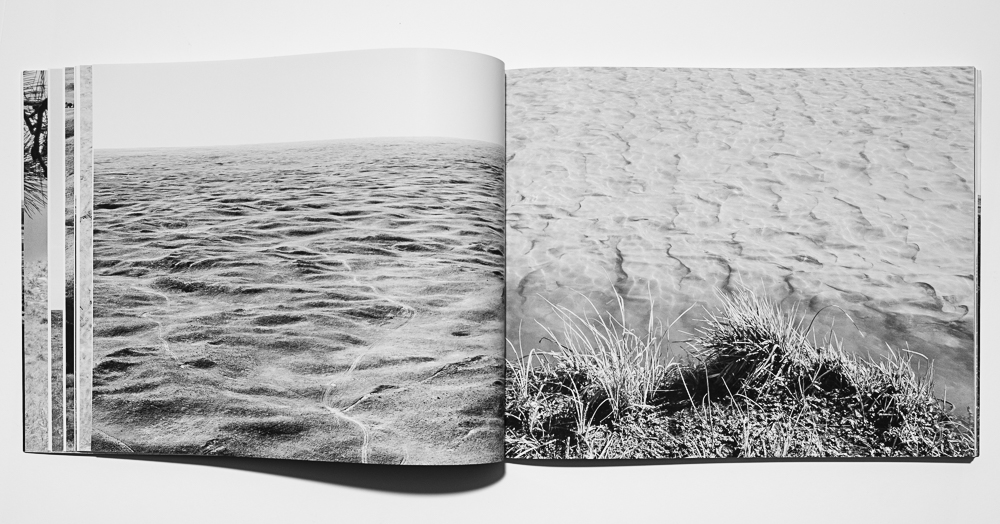

Field Guide to a Hybrid Landscape (2023, University of Nebraska Press,) reveals the human and non-human forces shaping what was once the world’s largest hand-planted forest in what is now the world’s largest intact prairie. Black and white photographs offer contrasts of patterns from the forces of sand, wind, water, planting, thinning, fire, decomposition, and sowing that contribute to its unique environmental history.

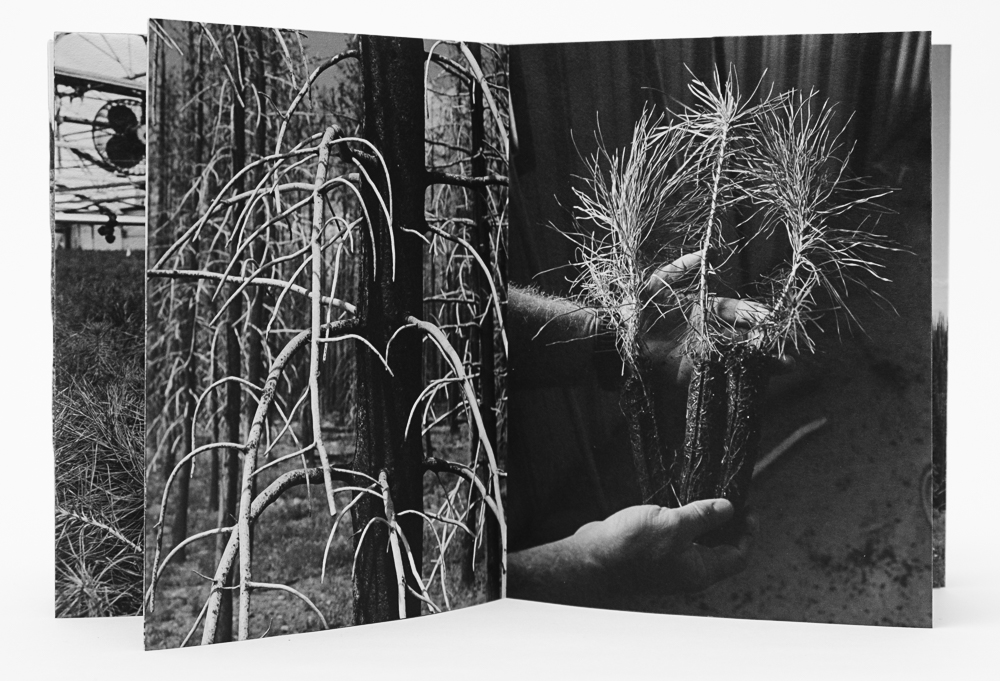

Post-fire Postscript (2024, hand bound artist book) follows the changes in land after a catastrophic wildfire swept through the hand-planted forest and grasslands. Over two years I photographed in the evolving fire scar and eventual clearcut and timber sale to create an artist book that acts as a companion and update to my trade book.

ES: What advice would you give to photography students?

DF: I think I must be spouting advice quite often, especially in my Capstone class. It is our last chance to prepare them for the increasingly precarious world as professional artists and sometimes it feels like a race against the clock. (I tend to stay in closer touch with our MFA alums, so our dialog is ongoing.) My general advice, aside from innumerable granular tips on grant writing, applications, proposals, lectures, studio business, etc, is: Show up for your work. There are no short cuts. (The only way is through.) You must find your people and maintain relationships. (This is made easier through the Society for Photographic Education.) Be kind. Our field is small and everyone knows everyone.

To follow is a small selection of images and statements from some of Dana’s students.

Rana Young, MFA 2017

I had the pleasure of working with Dana during my MFA residency from 2014–17 at UNL; she also served as my Thesis Chair. Her mentorship was nothing short of transformative—she cultivated an atmosphere of rigor, curiosity, and care that pushed me to grow as a maker, thinker, and teacher. Dana’s critiques were exacting and compassionate, urging me to dig deeper, refine my vision, and expand my artistic language. She modeled integrity and dedication in all aspects of her art practice and teaching, shaping how I approach my students and the studio. Perhaps most profoundly, Dana taught me how to be practical and intentional, instilling habits of organization and persistence that have sustained my career long after graduate school. I feel incredibly fortunate to share a close relationship with her today, and I continue to be inspired by her wisdom and unwavering support.

Zora J Murff, MFA 2018

I studied with Dana at UNL from 2015-18 and she taught me many things about being an artist and educator. Three lessons stick out the most, the first being how to cultivate a well-rounded studio practice. She showed me the importance of mapping out your desires, planning for how to get there, and becoming an effective communicator in helping others understand your vision. The second was the value of rigorous study. Dana was always attentive to individual student needs, which made her effective in both teaching how to find a center of your research interests and developing exciting ways of articulating unique ideas. Lastly, and most importantly, Dana taught me how to make art and teach with conviction; she helped me understand that what we do as makers, interpreters, and teachers of photography is meaningful beyond putting something pretty on a white wall.

Terry Ratzlaff, MFA 2021

I think of Dana as someone who always stood firmly behind her students. Her support was constant, and you always knew she was in your corner. In grad school, there were times when I felt that making sense meant not making sense—and that this was my answer to creative problems—and fortunately, Dana was there to bring her logical and rational perspective to a lot of my more outlandish ways of thinking.

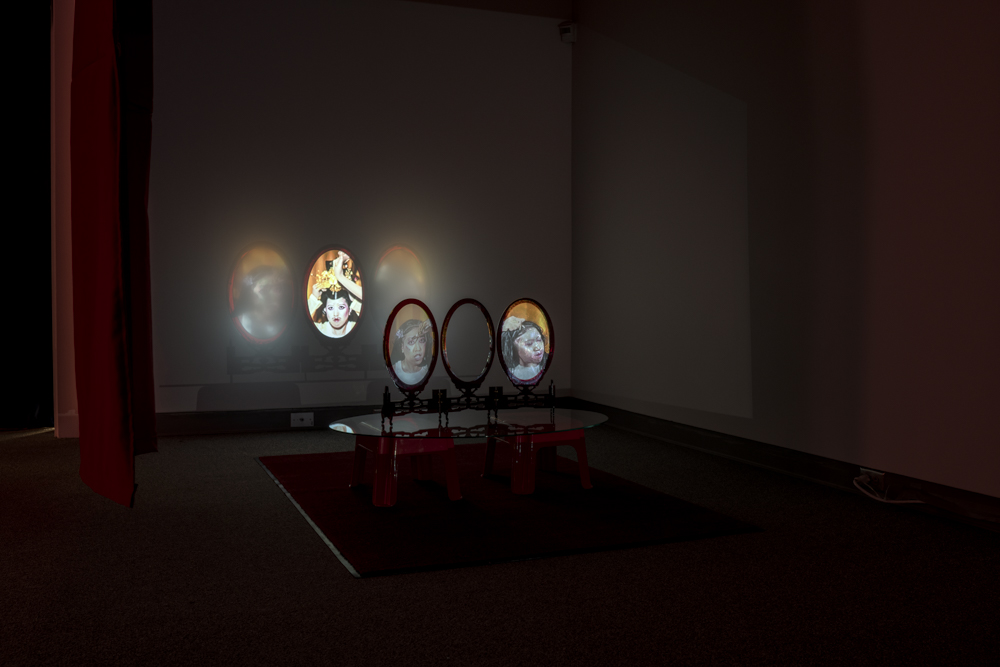

Jamie Ho, MFA 2023

Dana Fritz was my professor during my time at graduate school and has continued to champion my work during and still to this day. I have benefited so much from her mentorship as her approach to teaching and mentoring has deeply impacted my own approach with students. She cares not only about the trajectory of my work, but me as a person trying to succeed in a field that is notoriously difficult to navigate. Whenever Dana has visited my studio, she demonstrated her generosity and curiosity by providing feedback that is both insightful yet allows room for critical questions. I cannot express enough how deeply appreciative of her continued guidance and support.

About Dana

Dana Fritz holds a BFA from Kansas City Art Institute and an MFA from Arizona State University. Fritz is currently Professor of Art in the School of Art, Art History & Design at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln where she received the 2025 Annis Chaikin Sorensen Award for Teaching in the Humanities. Her honors include an Arizona Commission on the Arts Fellowship, a Nebraska Arts Council Individual Artist Fellowship, a Rotary Foundation Group Study Exchange to Japan, and a Society for Photographic Education Imagemaker Award. Fritz’s work has been exhibited widely in the U.S. as well as in Canada, France, Spain, the Netherlands, China, South Korea, and Japan. Her prints are held in collections including the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City; Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago; Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Pennsylvania; Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, Arizona; the Center for Art + Environment at the Nevada Museum of Art; and Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris. Fritz’s artist books are held in collections including Yale University’s Beinecke Library; the Museum of Fine Arts Houston’s Hirsch Library; Rare and Distinctive Collections at Colorado University Boulder; and Wellesley College’s Clapp Library.

Fritz has been awarded artist residencies at locations known for their significant cultural histories and gardens or unique landscapes: Villa Montalvo in California; Château de Rochefort-en-Terre in France; Biosphere 2 in Arizona; PLAYA in Oregon; Brush Creek Foundation for the Arts in Wyoming; Huron Mountain Wildlife Foundation in Michigan; and Homestead National Historical Park in Nebraska. Her work has been published in numerous exhibition catalogs including IN VIVO: the nature of nature, Encounters: Photography from the Sheldon Museum of Art, Grasslands/Separating Species, and Reclamation: Artist Books about the Environment, and also in The New York Times, Liberation, Harper’s, Orion, Border Crossings, Studio, and Photography Quarterly. University of New Mexico Press published her monograph, Terraria Gigantica: The World under Glass, in 2017. University of Nebraska Press published Field Guide to a Hybrid Landscape in 2023.

Upcoming Exhibitions

Selections from Field Guide to a Hybrid Landscape and Post-fire Postscript are included in From the Great Lakes to the Great Plains: The Visible Currents of Climate Change at Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts in Omaha, Nebraska through September 14, 2025.

The complete Field Guide to a Hybrid Landscape, Post-fire Postscript, and Re: forest are on view at the Museum of Nebraska Art in Kearney, Nebraska through January 4, 2026.

Website: www.danafritz.com

Instagram: @danafritzphoto

Facebook: danafritzphotography

Bluesky: @danafritz.bsky.social

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Erin Ryan StellingJanuary 9th, 2026

-

Time Travelers: Photographs from the Gayle Greenhill Collection at MOMADecember 28th, 2025

-

Photography Educator: Juan OrrantiaDecember 19th, 2025

-

Photography Educator: Lynn Whitney in Conversation with Andrew HershbergerNovember 14th, 2025