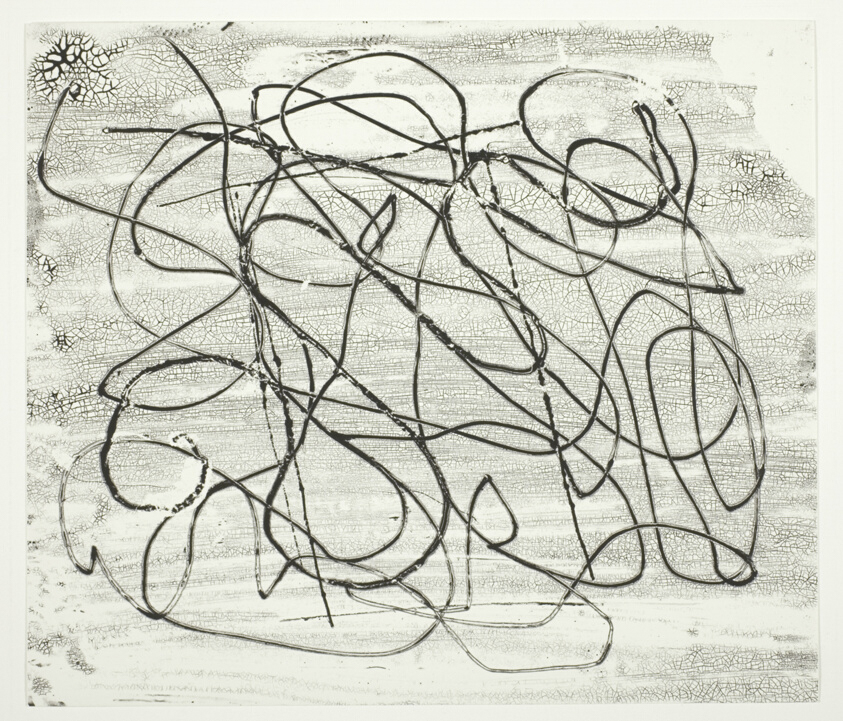

Vanishing from View | Cliché-Verre in Contemporary Photography

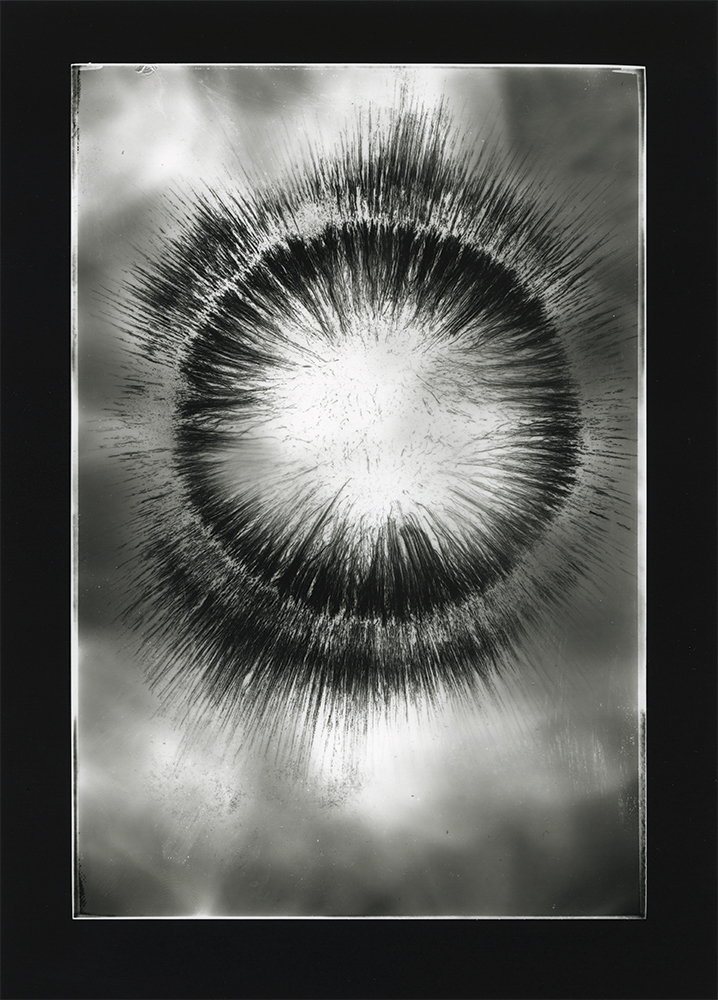

Discord, Naomi Savage, 1949, Gelatin silver print (cliche verre), from the portfolio Naomi Savage Portfolio XIX/XX (1981), Image/paper: 25.3 x 29.2 cm (10 x 111/2 in.), Gift of Terrence Donnelley, Art institute of Chicago.

Glass holds dimensions within it, of other worlds that lay just beyond it. In the right light, it can reflect our image back to us, and yet simultaneously we can peer beyond the raking light. A fingerprint can be seen; evaporated water lines, breathe upon it and it becomes a fogged surface, momentarily a canvas, able to be drawn upon. These fleeting curious happenings with transparent materials can penetrate our imaginations.

Glass is at the very essence of photography, without it, the medium would not exist, the first photographic impressions were made upon glass, but often it was designed to disappear, to be cleaned and made as invisible as possible. The cliché-verre is one such technique that pushes expectations of how translucency is used in photography. It harnesses the power of light through the manipulation of its use of glass to retain a unique photographic drawing. Derived from the French, cliché-verre loosely translates to glass plate, it is a technique which has continued to be shrouded in mystery, a process falling somewhere between painting, printmaking and photography.

Over the years, the cliché-verre has alluded to any one simple classification. Often housed in both print collections as well as photography in institutions, the definition of a cliché-verre is either debated or unknown. There have been many ways of labeling the process, such as glass print, etching on glass, photogenic etching, and cliché photographique sur verre, are only a few of the names in which the technique has been identified throughout its long life.

Souvenir of Bas-Bréau, Jean Baptiste Camille Corot, 1858, Cliché-verre on ivory photographic paper, 18.4 × 15.1 cm (7 1/4 × 6 in.), The Joseph Brooks Fair Collection, Art Institute of Chicago.

Fontainebleau Forest, Eugène Cuvelier, early 1860s, Salted paper print from paper negative, 19.8 x 25.8 cm (7 13/16 x 10 3/16 in.), Purchase, The Howard Gilman Foundation and Joyce and Robert Menschel Gifts 1988, Met Museum

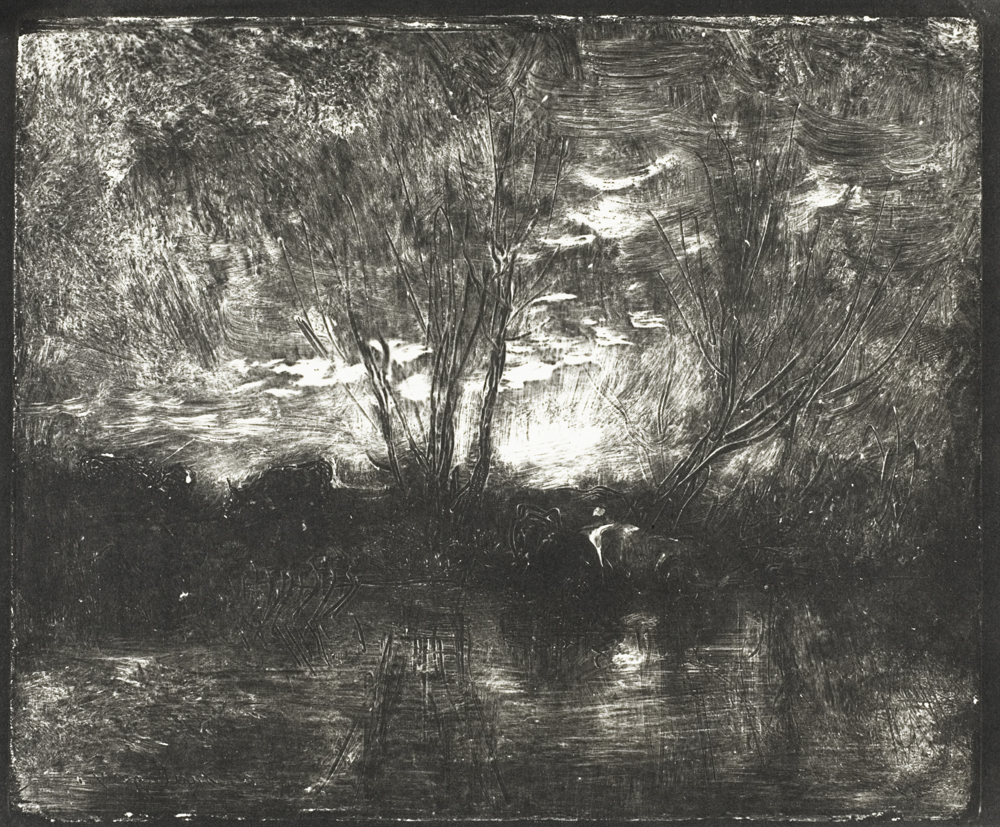

First used in 1853 in collaboration with prominent French romantic landscape painters including Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Charles-François Daubigny, and Jean-François Millet. Initially made popular by the photographer Eugene-Adalbert Cuvelier and drawing professor Jean-Gabriel-Léandre Grandguillaume, the cliché-verre was used as a technical innovation to replicate their drawings through a process considered less cumbersome than lithography. The painters instead of using a copper plate or wood cut would draw directly onto treated glass plates assisted by Cuvelier to make reproducible photographic impressions.

A cliché-verre plate is created manually either by etching away an opaque material or through additive means of drawing upon a translucent substrate. Once the composition is complete, the plate becomes an analogue, akin to a photographic negative, exposed in direct contact to light-sensitive paper to create a photographic image.

Cows at the Watering Place, Charles Francois Daubigny, 1862, Cliché-verre on ivory photographic paper, The Charles Deering Collection, Art Institute of Chicago, 14.8 × 18.5 cm (5 7/8 × 7 5/16 in.)

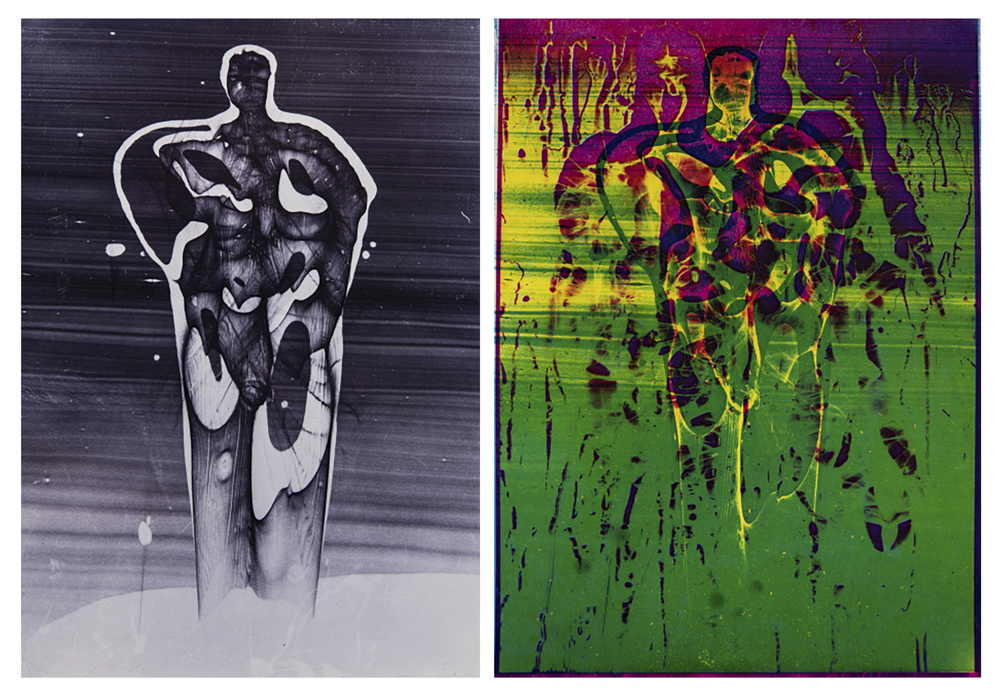

Giant, Henry Holmes Smith, Dye transfer prints, 8 13/16 x 6 3/16 in. Henry Holmes Smith Archive, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University

The technical innovation of the cliché-verre brought a playful, experimental and airy quality to the replication of the talented romantic painters’ drawings. Working in the open air of the landscape, Camille Corot would use a stick or the blunt end of his paint brush to etch into the printer’s ink on glass, creating wispy, erratic shapes and lines dancing in the light, to then be exposed by the same sun from which the drawing was rendered. The haziness of trees in Camille Corot’s landscapes were influenced by photographic blurring that resulted from the motion of leaves during the long exposure periods required in photography. Both his methods of drawing and painting, as well as his range of tones, seemed to be derived in part from his love of photographs1 The cliché-verre technique opened a door of opportunity for creative co-mingling to take place between two mediums. For one of the first times in art history, these painters were momentarily multimedia photographic artists.

However, as with many other processes during this time of the swift and fast paced rise of photography in the 19th century, the cliché-verre quickly fell into obscurity. Its means as a tool to replace lithography or wood cutting was not seen to be efficient but rather cumbersome and confusing. Although its mechanical reproductive nature was not sufficient, it did ignite a profound collaboration between painter and photographer. Gesture, chance, mark making and all the elements of painting were introduced in a unique way never seen before in such detail with the photographic print. The cliché-verre technique can be remembered as the first interdisciplinary photographic artform, allowing artists to harness the power of sunlight to render their works.

The cliché-verre has since nearly vanished from view, ebbing in and out of the memory and discourse of photographic history, yet secretly holding a lasting impression on the imaginations of many artists throughout its obscure life. Over the last 175 years, the cliché-verre has found its way into the repertoire of a subset of prominent visual artists including; Barbara Blondeau, Heinz Hajek-Halke, Sameer Makarius, Jack Sal, Naomi Savage and Henry Holmes Smith, to name a few. Their cliché-verre works open a window into seeing another world of their artistic practices. Glimpses of a sincere experimental nature and a wondrous curiosity of alchemy can be found within the cliché-verre’s unique ability to manipulate material and entice new ways of seeing.

Vanishing but not entirely forgotten, the cliché-verre technique holds a unique stance in contemporary artists’ practices. The earliest form of the cliché-verre used smoke soot over fogged collodion on glass that was etched into. Over time, chosen materials used for drawing with and articulating the final image have become unexpected and expansive. Artists have continued to gravitate to the technique as a means to turn the familiar into the strange, with their final results becoming beautifully atmospheric, inscrutable and wonderfully puzzling.

Coal and Glacier Water Cliché-Verre #5, Shoshannah White, 2019/2024, Scanned and printed on Kozo, 36 x 36 in, courtesy of the artist

The cliché-verre allows for the suggestion of an idea as to what we are looking at, and there continue to be endless results which can be obtained through the handling of an artist’s chosen translucent material. In Fredick Sommer’s paint on cellophane works, a body emerges and hovers upon black space, evoking a spirit-like figure. The paint on cellophane, by chance, elicites a human torso, almost like an X-ray. Barbara Blondeau’s Victim,1966, brings a visceral and haunting vulnerable image of a human form in profile as if in a state of decay.

In 1970, Henry Holmes Smith discovered the cliché-verre, his drawing tools were household materials such as corn syrup manipulated through light play to create an amebic family of distorted and disorienting human-like figures. Balance and harmony is quietly made in the work of Jack Sal in No Title #2 from 1985, interior monologues of the mind are scribed within acrylic on plexiglass. Printed using the cibachrome method, Sal’s work offers a poetic connection to the vernacular and history of painting through mark making and the handling of paint.

When the world is held under a microscope or expanded to such a large scale, magic takes place and can transcend our expectations as to what we are truly seeing. The alchemical nature of Shoshannah White’s work is produced through this intensity and practice of looking. Using glacial ice and coal as her drawing medium, White brings the smallest details forth for us to meditate on the fragility of the natural world.

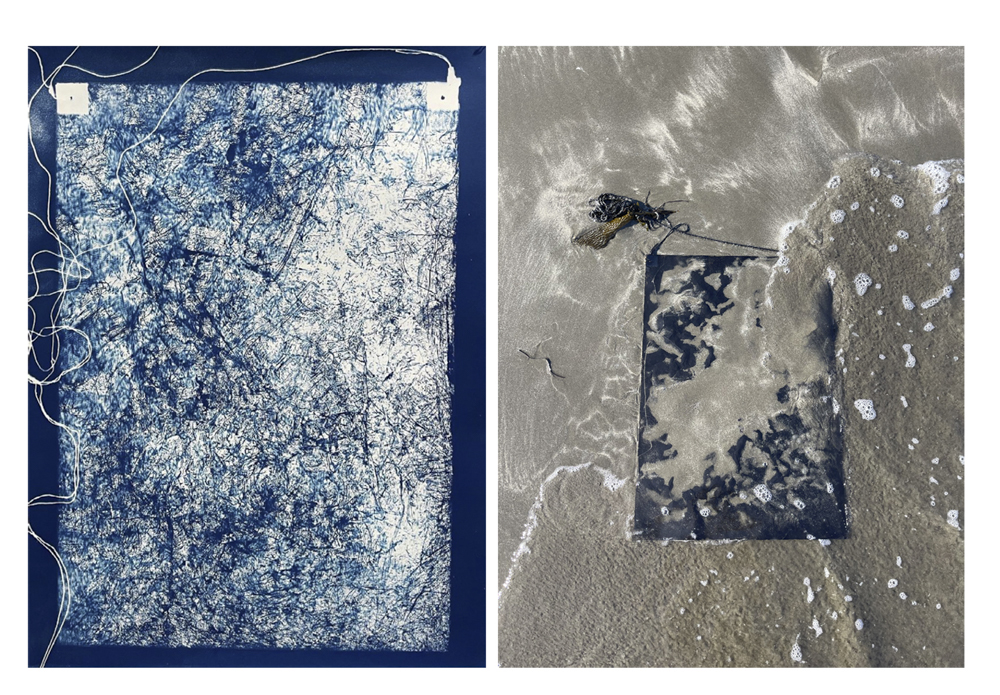

Four Cardinal Directions : East, Governors Island, New York, Betsy Kenyon, 2019, Hand-coated cyanotype print on platine paper 40 x 30 in. courtesy of the artist

Betsy Kenyon’s negatives are created from mylar sheets coated in sumi ink, thrown into the surrounding waters of the four cardinal points of the contiguous United States.Their results are memories of the water’s movement, trusting chance and collaboration with the natural elements. Erratic, yet calming, the results of Kenyon’s cliché-verre series brings back the processes’ first historical uses, one that is connected to the intimacy of nature, in plein air, and printed through harnessing the power of sunlight.

Automatic Magnetic Field Drawing XXI, James Baroz, 2025, Silver gelatin print, 5 x 7 in. courtesy of the artist 9. Cliché Verre, Alexandra

Cliché Verre, Alexandra Leykauf, 2018, Photogram prints on photographic paper, courtesy of the artist

In James Baroz’s Automatic Magnetic Field Drawing XXVI, 2025, the unseeable is stilled momentarily using the cliché-verre, magnetic fields draw themselves that otherwise may go unnoticed. Alexandra Leykauf’s prints were made using the natural cause and effect of the light casting through her drawings upon the windows at night. The works become abstracted living landscapes that are experiments in trial and error. A memory of the light is retained on silver gelatin paper, the architecture’s glass windows becoming the artist’s ‘negative’.

Paint on Cellophane, Fred Sommer, silver gelatin print, 1958 © Frederick & Frances Sommer Foundation.

Victim, Barbara Blondeau, 1966, cliché-verre silver gelatin print, 23 ⅝ x 20 ⅞ in. © 1976 Visual Studies Workshop, Rochester, New York

Evocative and transformative, the cliché-verre technique has endless potential, it has evolved as a tool that can allow science, art and poetry to touch equally through the photographic process. Heinz Hajek-Halke once said of his photographic practice that there were ‘two difficult aspects that have always overshadowed (his) character…defiance and curiosity, so it came to pass that (he) became a photographer in spite of a background in academic painting; and remained a painter in spite of being a photographer.(2”)

What was once a failed tool of mechanical reproduction, the cliché-verre has since been appropriated to push the expectations of photography further and foster greater curiosity in the world surrounding us.The photographic practice has always been determined to be manipulated, pushed and defied, and it is through the use of the recurring curiosity of the cliché-verre technique that artists can continue this beautiful defiance.

1 Coke, Van Deren. ‘The Painter and the Photograph: From …’, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, NM. 1986

2 Siben, Isabel. Fantasy and Dream – the Late Light-Graphic Work of Heinz Hajek-Halke, exh. cat. Deutscher

Kunstverlag, 2008

Südliche Erinnerung, Heinz Hajek-Halke, 1957, gelatin silver print, negativmontage aus verschiedenen gezeichneten Elementen, Fensterrahmen Heinz Hajek-Halke Estate, Courtesy CHAUSSEE 3

Feverfew, Marcy Palmer, 2022, pigment print on mulberry paper, gold leaf, 11 x 14 in. courtesy of the artist

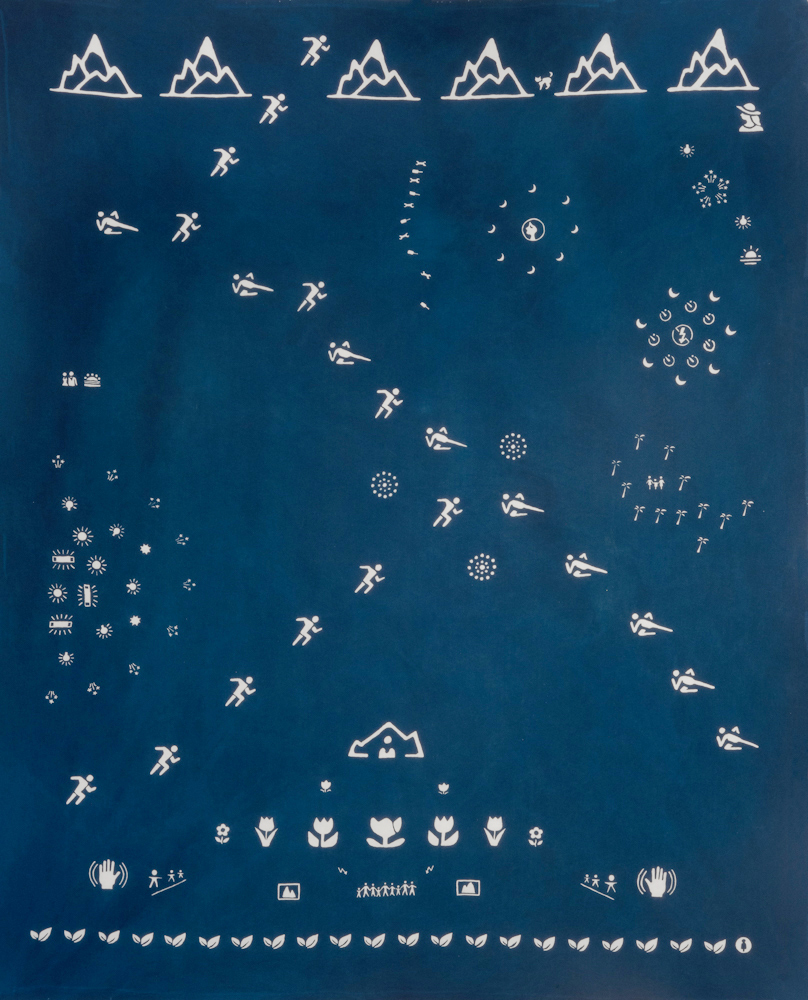

My Generic Life: A Scene Mode Autobiography, Meggan Gould, 2019, cyanotype on muslin, 40in x 32in. courtesy of the artist

Daniel Hojnacki (b.1989) received his MFA from the University of New Mexico in 2022 and a BA from Columbia College Chicago 2011. He is a recipient of the Penumbra Foundation Workspace Artist-In-Residence, The Patrick Nagatani Photography Scholarship, The Phyllis Muth Arts Award, among other honors. He has exhibited work at the Museum of Contemporary Photography, University of New Mexico Art Museum, and the Chicago Cultural Center. His work has been featured in Aint-Bad, Pamplemousse Magazine and Southwest Contemporary Magazine. He is represented by 203 Fine Art in Taos, NM, and he currently lives and works in Chicago, IL

Instagram: @d_hojnacki

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026

-

Carolina Baldomá: An Elemental PracticeJanuary 5th, 2026