Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Cathy Cone (2023) and Takeisha Jefferson (2024)

Photolucida is a Portland-based nonprofit dedicated to providing platforms that expand, inspire, educate, and connect the national and international photography community. Critical Mass, Photolucida’s annual online program, is designed to foster meaningful connections in the photography world. Open to photographers at all levels, anywhere in the world, participants submit a portfolio of 10 images. Following an initial pre-screening, 200 finalists are selected to have their work reviewed and voted on by up to 200 distinguished international photography professionals. From this process, the Top 50 are chosen, and a range of awards is presented. Submissions open each June.

In 2025, we celebrate the twentieth year of announcing the Critical Mass Top 50 finalists! We are honored to partner with Lenscratch to reflect on this history through a special series highlighting two artists from two different years in each post. Each featured artist offers a window into the diversity of projects and voices that make up Critical Mass—from documentary and narrative photography to conceptual, photo-based practices. These Q&As share the history, intention, and trajectory of the artists, pairing their Critical Mass portfolios with newer work.

For Critical Mass 2025, we received submissions from artists across 26 countries, tackling subjects in countless styles—from black-and-white and digital photography to chemigrams, cyanotypes, photographic sculpture, and textiles. Our esteemed jurors, representing a wide range of global perspectives, dedicate their expertise and thoughtful consideration to this process, often leaving feedback and encouragement for the artists.

Critical Mass continues to elevate emerging photographers, providing a platform that amplifies their voices to broader audiences and to the industry professionals who help shape careers. We are deeply grateful to everyone who makes this possible.

Cathy Cone 2023

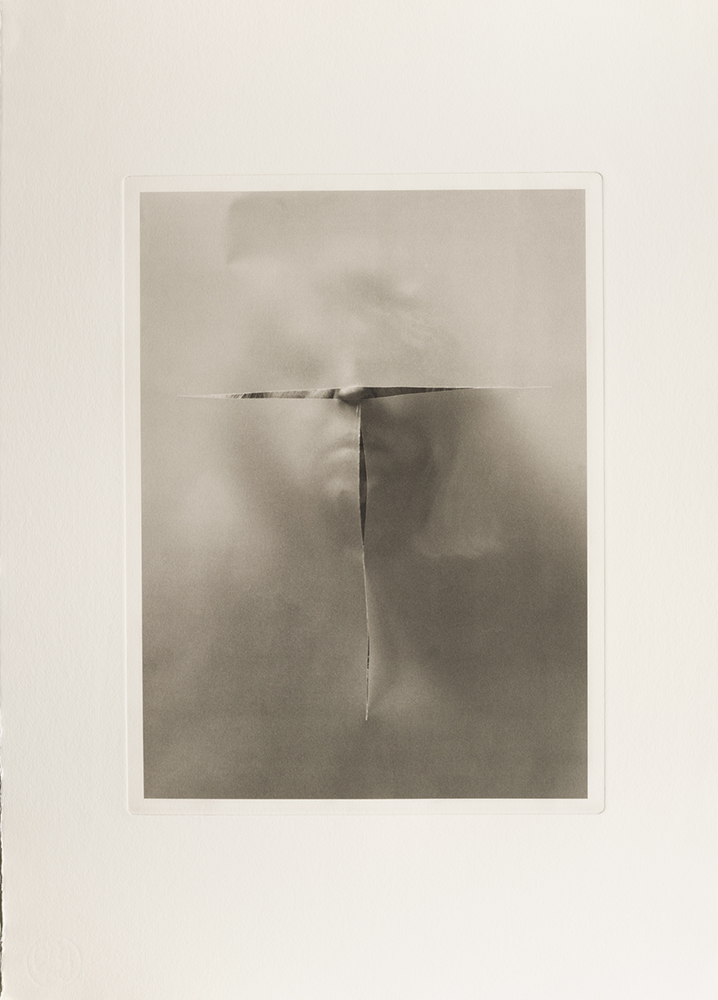

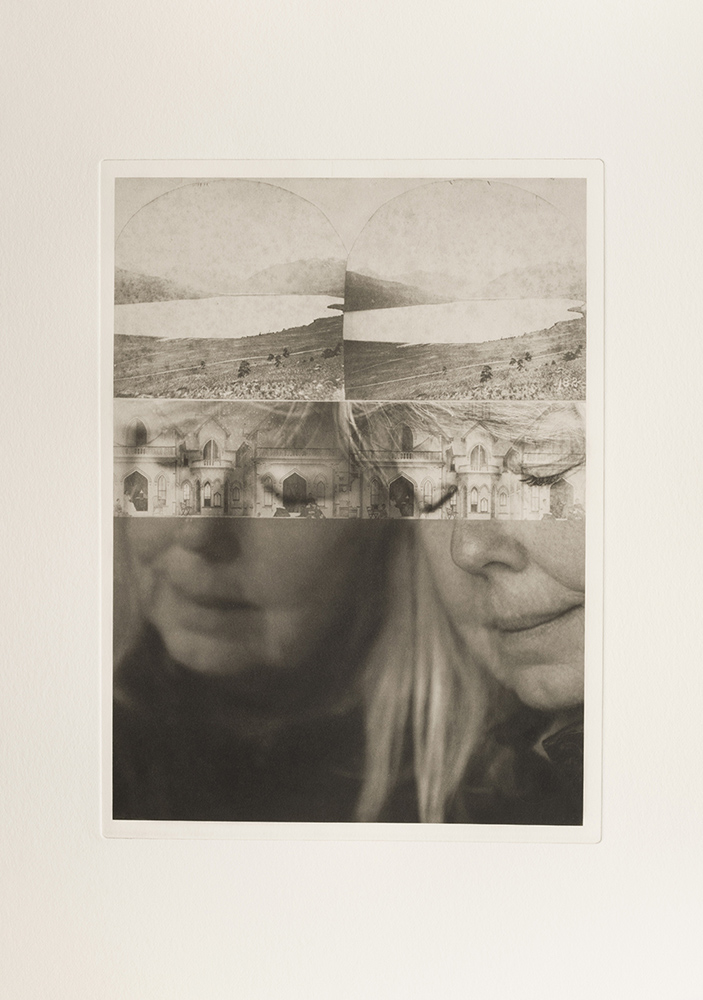

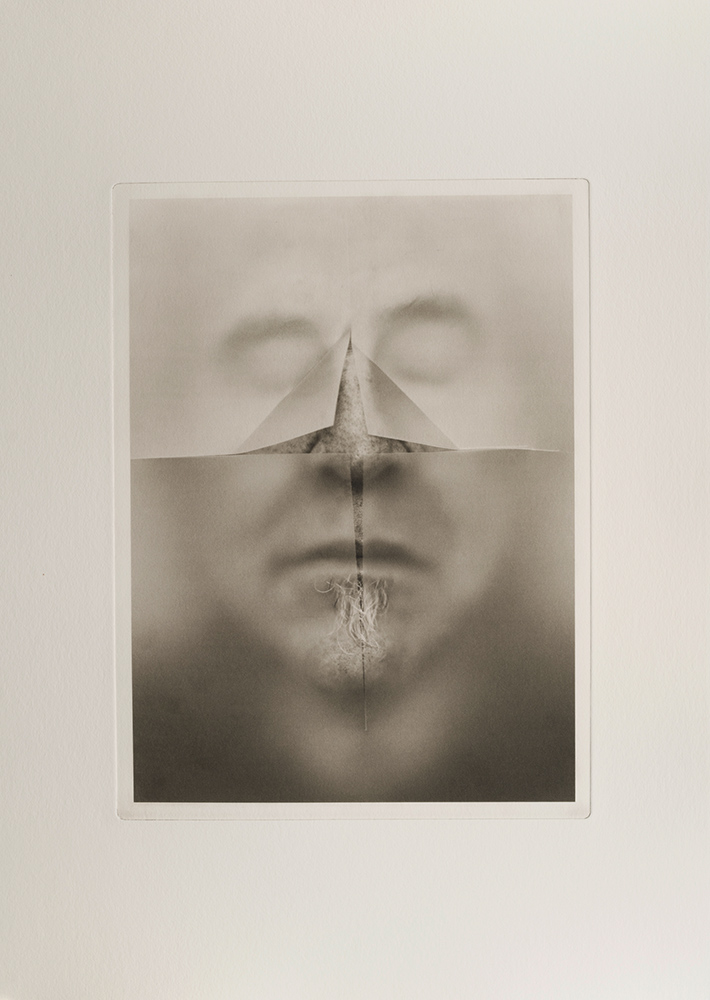

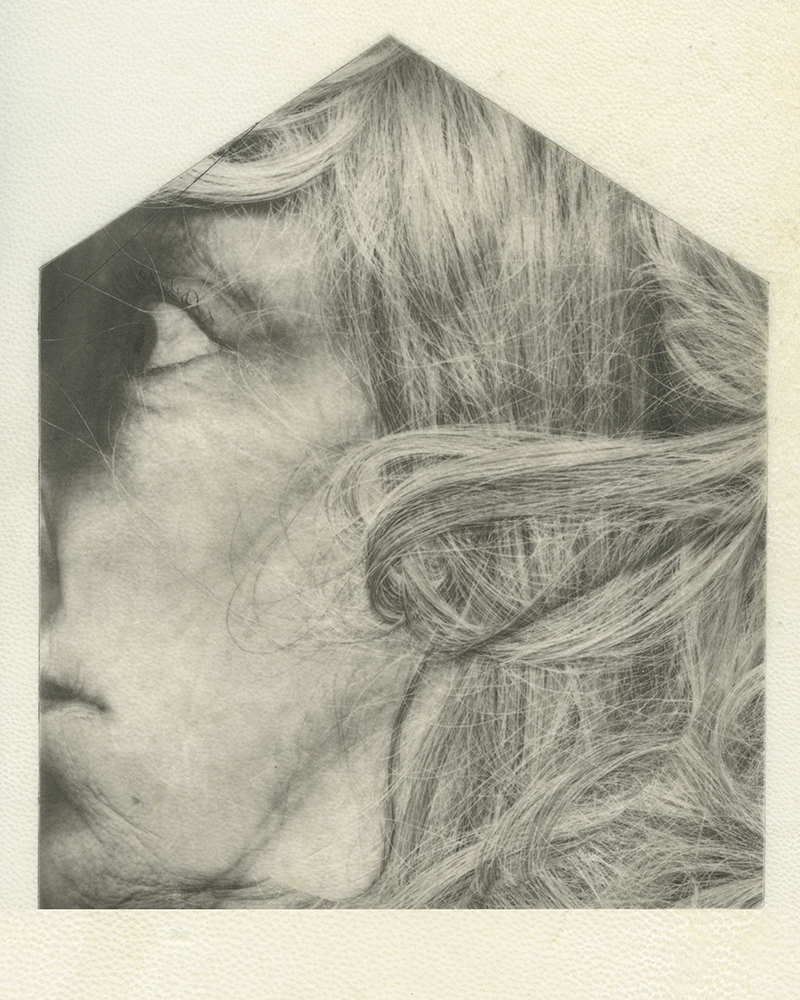

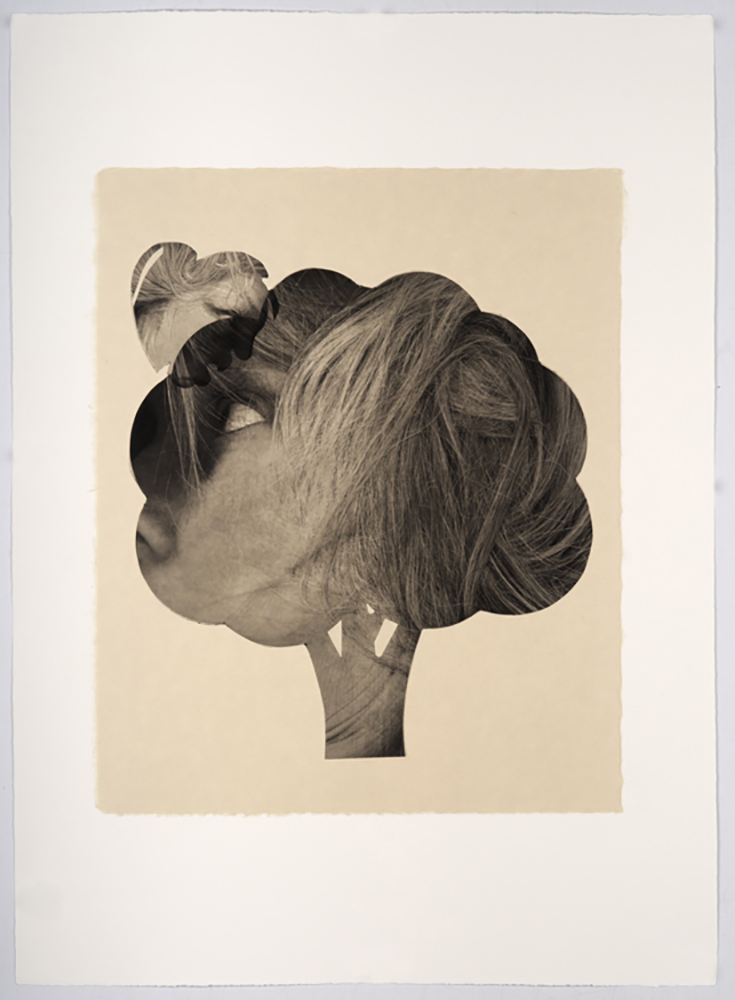

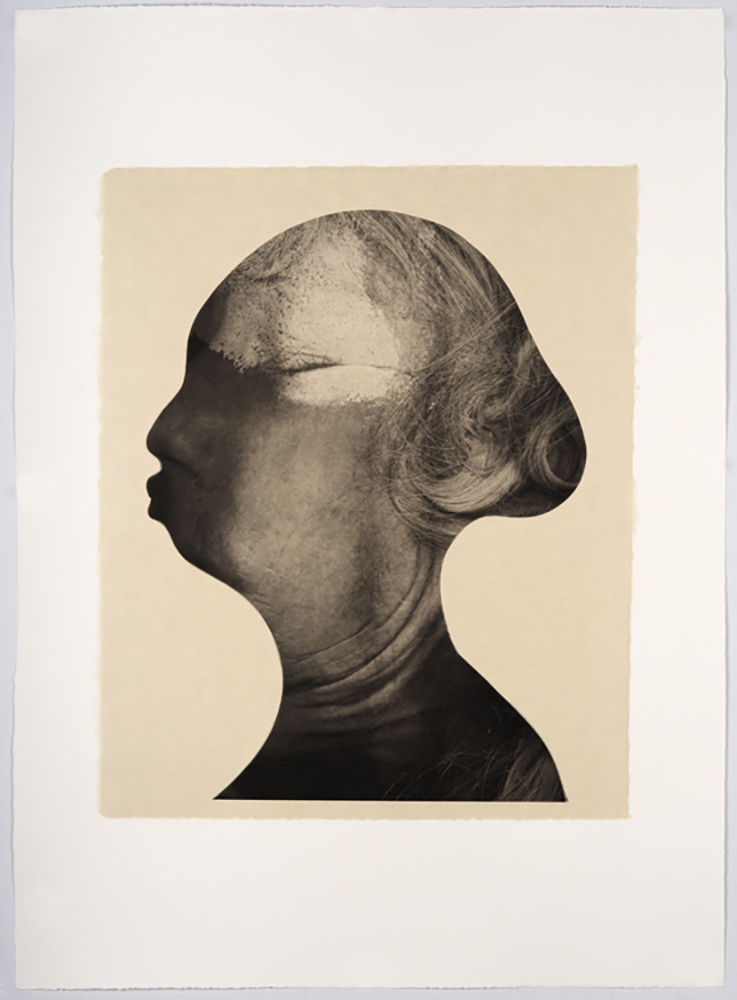

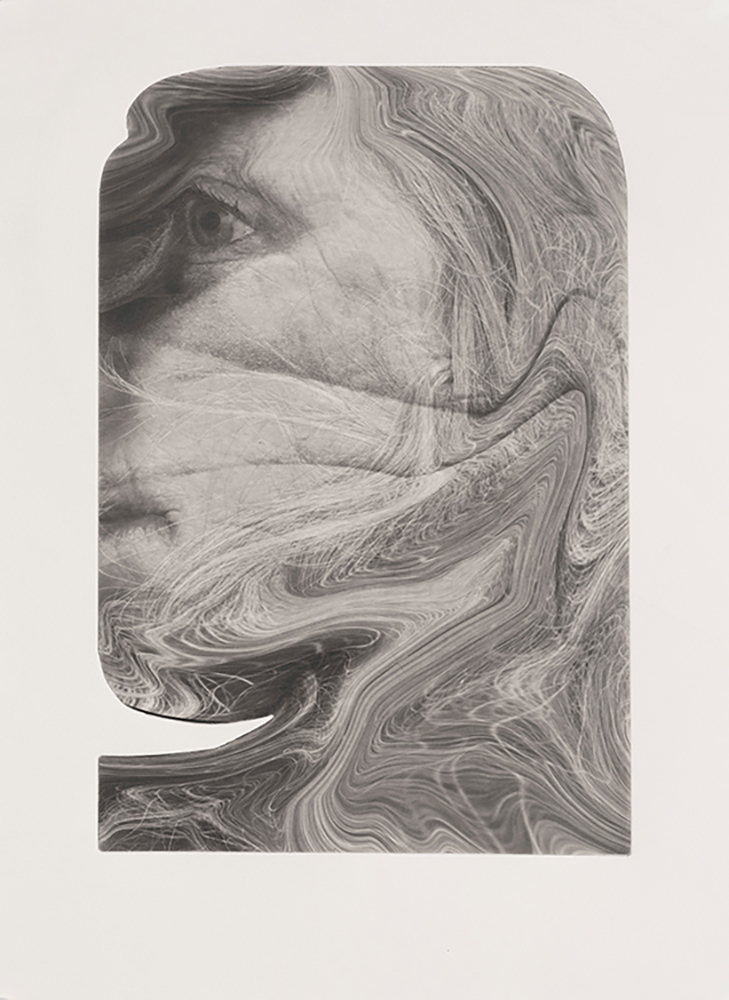

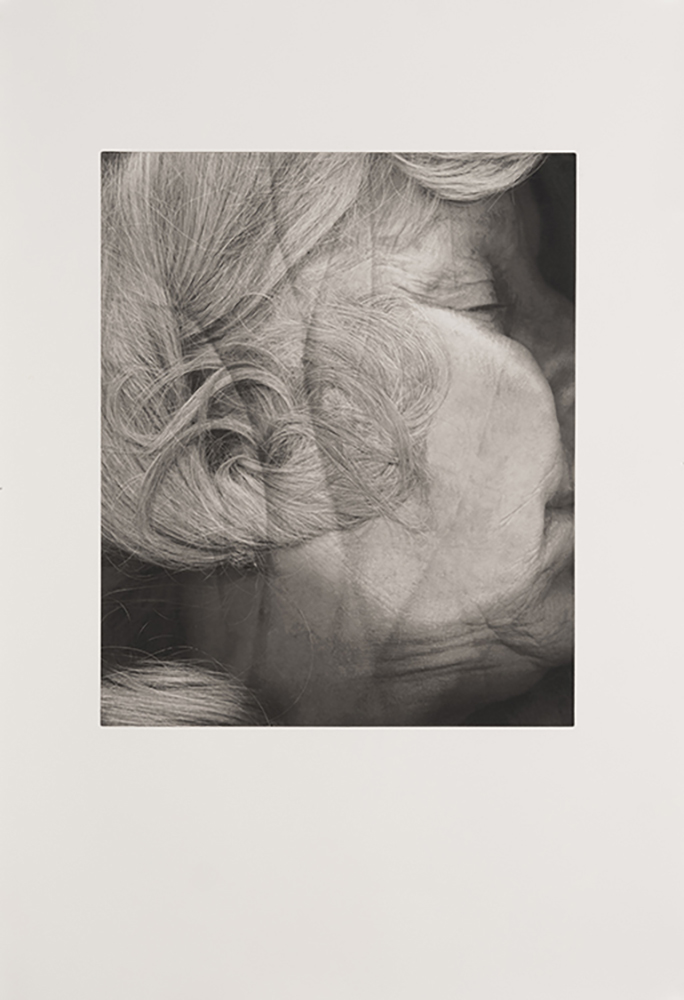

In Apparent Close-Up, her 2023 Photolucida Critical Mass Top 50 portfolio, Cathy Cone bends portraiture into a layered, dreamlike state. Working with photogravure, stitching, and distortion, she transforms the human face into a site of memory, revelation, and inner mapping. Her practice bridges analogue and digital processes while drawing on influences as varied as tai chi, meditation, and family history. In this conversation, she reflects on how residencies, generational stories, and material experimentation continue to expand her understanding of portraiture and the human condition.

Cathy Cone is a photographer, painter and printmaker. Her surrealist approach to photography began in the late 1970’s with the introduction of the “Diana” camera. This led to investigation of experimental techniques towards a multidisciplinary approach to her poetic image making. Cathy received her training at Ohio University, Vermont Studio Center. She received her MFA at the Maine Media College where she served as a mentor and guest faculty. Some of her exhibitions include Sewanee: University of the South, Weisman Art Museum, University of Alabama, DeCordova Museum, Griffin Museum of Photography, Brattleboro Museum and Art Center and the Vermont Center for Photography. Her works are in the collection of IBM, Hallmark Fine Art Collections, American Express, Beekman a Thompson Hotel, New York and many private collections. Cathy with her husband, master printer Jon Cone, founded Cone Editions Press in 1980 in Port Chester, NY as a collaborative printmaking workshop. Cone Editions Press is now located in East Topsham, Vermont where Cathy is director of the Workshops and Studio.

Instagram: @cathy_cone

Q: How did you first learn about Photolucida’s Critical Mass, and what motivated you to enter?

CC: I first learned about Photolucida’s Critical Mass while pursuing my MFA at Maine Media College. It felt like an invaluable way to connect with a larger photographic community, continue exploring the medium, and publicly share my work.

Q: In your 2023 Critical Mass Top 50 portfolio Apparent Close-Up, you photographed and re-photographed through the transparent cover of the photopolymer plate. How did this process of layering and distortion shift your understanding of portraiture?

CC: I was looking for a way to deepen the psychological dimension of the portrait. The transparent film covering the plate—part of the direct-to-plate photogravure analogue/digital process—introduced a dreamlike distortion. It intuitively added a multi-layered, interior quality that opened up new ways of seeing and experiencing the portrait.

Q: You describe veiling as a form of unveiling. How do the acts of stitching, marking, and layering transform the images into sites of revelation rather than concealment?

CC: I’ve practiced martial arts and tai chi for many years, and both traditions hold hidden truths that are revealed through repetition. One of my meditation teachers once told me that we learn everything through its opposite—except for the divine mystery. That wisdom resonates with my practice. The mark-making and stitching created an active dialogue, a process of asking “what if,” where concealment often revealed more than it hid.

Q: The series fuses past and present into a multi-sensory experience distilled within a single image. How do memory and lived experience shape the portraits in Apparent Close-Up?

CC: These images are layered with fragments of memory and experience, each comprised of many different moments. The portraits become distilled histories—evidence of lived experience re-shaped in a nonlinear, evolving way.

Q: The project emerged during your residency at the Tusen Takk Foundation in 2022. In what ways did the environment or conditions of the residency influence either the conceptual development or technical execution of the work?

CC: The immersive setting on the Leland Peninsula next to Lake Michigan gave me quiet and focus. Just as important, it was a collaboration with my husband, master printer Jon Cone. The residency provided protected time, an incredible studio, and Jon’s technical mastery—all of which allowed me to fully concentrate on vision and image-making. It was simply magical.

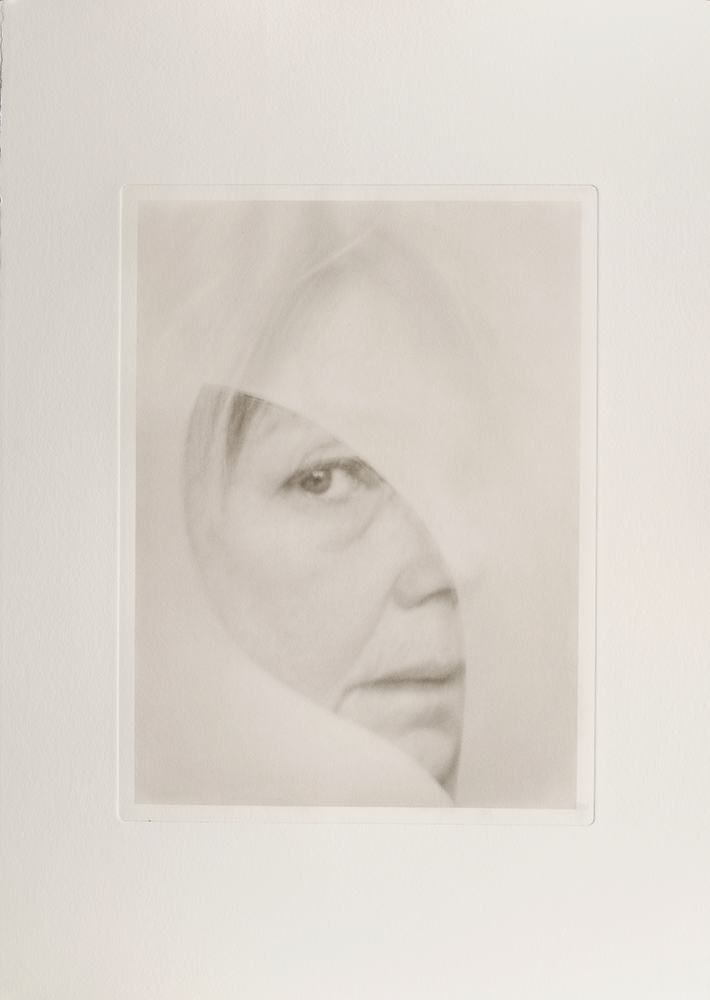

Q: In your Return series, you began by pressing your face against a scanner, creating distortions that opened unexpected visual possibilities. How did this unconventional starting point reshape the way you approached portraiture?

CC: The scanner’s inherent distortions freed me from expectation and offered surprising new perspectives. I first used scanners in the 1990s to make images of hair and found objects, sometimes adding paint. Returning to it for portraiture felt like visiting an old friend—one that opened new ways of working.

Q: Your reflections on aging, beauty standards, and your grandmother’s visible birthmark bring a deeply personal dimension to Return. How have these generational experiences influenced your exploration of visibility, imperfection, and self-perception?

CC: In Return, the scanner became a tool for mapping imperfections, magnifying them into terrain. My grandmother’s story has become my guide and my strength—what I once thought of as a limitation I now see as a superpower. It’s a map, but not the territory.

Q: Cutting a rectangular photogravure plate into the shape of a house was both a bold and symbolic act. How does this archetypal form connect to ideas of longing, memory, and belonging within the portraits?

CC: Shaping the plate into a house grounded the work in a symbolic and spiritual way. For me, it became “the long way home,” a metaphor for longing and belonging.

Q: You describe weaving an “interior fabric” that highlights a psychological or soulful existence beyond outward appearance. In what ways does the photogravure process itself help reveal this inner dimension of the human face?

CC: Photogravure’s physicality and hand-made qualities naturally extend the image. I wasn’t interested in simple reproduction but in the infinite variations the process could generate. That openness created a more intimate dialogue, one that revealed an inner dimension and led me toward more authentic portraits.

Q: Finally, how has recognition as a Critical Mass Top 50 artist shaped your career—whether through immediate opportunities or in the longer arc of your artistic practice?

CC: Being selected for Critical Mass Top 50 was both professional recognition and personal validation of my process and dedication. It affirmed the value of exploration in my work, which means everything to me.

Takeisha Jefferson 2024

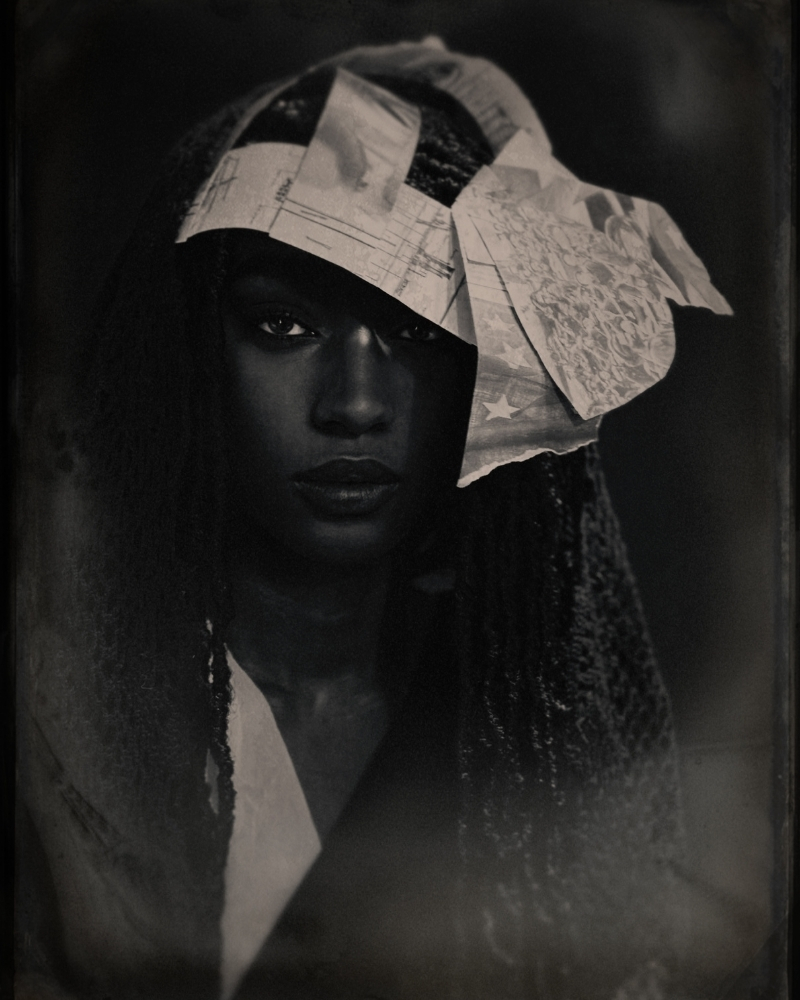

Takeisha Jefferson’s work is rooted in testimony—her own and that of her ancestors. A 2024 Critical Mass Top 50 finalist, her series Testify reclaims narratives too often erased, confronting the ways history has been distorted and censored, particularly around the lives of Black women in America. Through reimagined Civil War texts, intimate family portraits, and echoes of early photographic processes, Jefferson challenges audiences to reckon with both personal and collective memory. Her practice insists that visibility is not a gift but a right, and that art itself is a form of evidence—a way of testifying to presence, resilience, and truth.

Takeisha Jefferson is an international portrait photographer and artist, based in Michigan. Her artistic journey developed during her time as a Public Affairs Specialist, serving in the Air Force. Shortly after that she established a successful photography business and continued to refine her craft at Auburn of Montgomery University. During this time, she expanded her Birthright Series and developed a deep passion for art history.

Takeisha Jefferson’s talent and dedication have led to her participation in over 50 global exhibitions. Her work has garnered recognition, including a nomination for the Lecia Oskar Barnack Award and a feature on Google Arts and Culture. Her art revolves around significant themes such as family, black womanhood, and empowerment.

One notable accomplishment in her career was being featured in “As We See It – Redefining Black Identity,” a publication from the UK that showcased 30 global artists. Takeisha Jefferson’s artistic practice has been greatly influenced by her experiences as a disabled veteran, wife, and mother of four, adding depth and richness to her work.

Instagram: @takeishaart

Q: Can you share how you first learned about Photolucida’s Critical Mass and what motivated you to enter the competition?

TJ: Photographer Mara Magyarosi-Laytner changed everything for me. During my artist talk for Testify at the Nova 24 photo + film festival in Detroit, which she co-founded, she came up to me and said: “You need to submit this work to Critical Mass. Testify. This exhibition. Submit this.”

She told me I had only two days before submissions closed. I applied that weekend.

What began as her advice quickly became something larger. Ten to fifteen other artists gathered around as she explained Critical Mass. She created space for all of us—no gatekeeping, just encouragement and information.

I’m forever grateful. She saw my work and refused to let the opportunity pass. That’s the kind of support our community needs more of.

Q: Your 2024 Critical Mass Top 50 portfolio Testify explores how dominant narratives often overshadow truth, particularly in the history of people of color in America. How do you see your work reshaping—or reclaiming—those narratives for future generations?

TJ: With every exhibition, I claim space for Black women whose perspectives have too often been filtered through someone else’s lens. Testify pushes back against those borrowed vantage points. Our voices carry authority. Our truths matter.

My ancestors fought in the Civil War. Some were enslaved. Others fought for freedom. That layered history gives me both the right and the responsibility to tell the story differently.

I’m also an Air Force veteran. My family has served this country for generations. We’ve earned the right to tell our own stories.

Look at art history: most images of women’s bodies were made by men; most portrayals of Black life came from outside our communities. We need the chance to show what we see—what we saw—what we hope to see.

Our history is being erased even now. What little access we had was already sanitized. In a time when reading was once illegal for my ancestors, repurposing literature to confront those lies feels beyond poetic

Q: In Testify, you weave together personal and collective histories. How does bringing your family’s story into the broader American narrative shape the way audiences connect with the work?

TJ: History becomes real when it has a face. I begin with my own family—people whose names were erased, and people whose names were celebrated at our expense. I carry both lineages, and I refuse to flatten either one.

When audiences encounter my work, they aren’t looking at abstractions. They’re meeting witnesses. They’re seeing the ripple of choices and consequences that still shape our present.

My family is American. They’ve been here for generations. My family also includes the people who enslaved them. That truth needs to be told. People say we should move on, stop talking about the past—yet they fight to keep Confederate statues standing. If those stories are worth preserving, then so are mine.

Family grounds history in flesh and memory. It leaves no room to look away.

Q: By repurposing books on the Confederacy and the Civil War, you echo current efforts to restrict access to certain histories. What do you hope viewers take away from the parallels between these altered objects and today’s debates over education and censorship?

TJ: I love books. I don’t even like dog-eared pages. Cutting into them felt like a violation—but that tension is the point.

I bought every book secondhand, in part to take them out of circulation from people who romanticize the Confederacy. Those volumes already carried violence in their pages. Altering them was my way of stripping away reverence for the lie and exposing the mechanics of control.

And then I began watching what’s happening across the US: classes pulled from schools, universities challenged over curricula, DEI programs dismantled nationwide.

People need to see what censorship looks like. Enslaved people risked punishment for trying to read. Now students risk ignorance because truth is withheld. Different century, same fear of knowledge.

If viewers are upset by my headpieces made from torn Confederate texts, that’s fine. Let’s talk about why I’m angry—why we are angry. People never worried about my comfort when they removed my history from classrooms. Why should I protect theirs?

I’ve altered pages from one book. Others are banning hundreds, even thousands. The parallels aren’t theoretical.

Q: You’ve said that Testify is not only about the past, but also about how we engage with history in the present. How do you see art—distinct from academic or political discourse—cultivating the kind of critical thinking you believe is essential in this era of media saturation?

TJ: Art is evidence. It preserves how we lived, what we valued, and what we resisted. That’s why, in times of conflict, art is often destroyed first—it holds memories that cannot be silenced.

Art shapes our understanding of everything. We study pottery, poetry, architecture to know what came before. That’s why I called the series Testify. In a courtroom, testimony determines which version of events becomes “truth.” Who gets to testify in art history? Who gets to say what happened?

When someone stands before my images, they aren’t reading theory or legislation. They’re in direct conversation with a witness. That immediacy is what art makes possible.

Art carries a voice in ways academic writing and political debate cannot. When you stand in front of my work, you hear my testimony directly. No filter. No interpretation. Just witness.

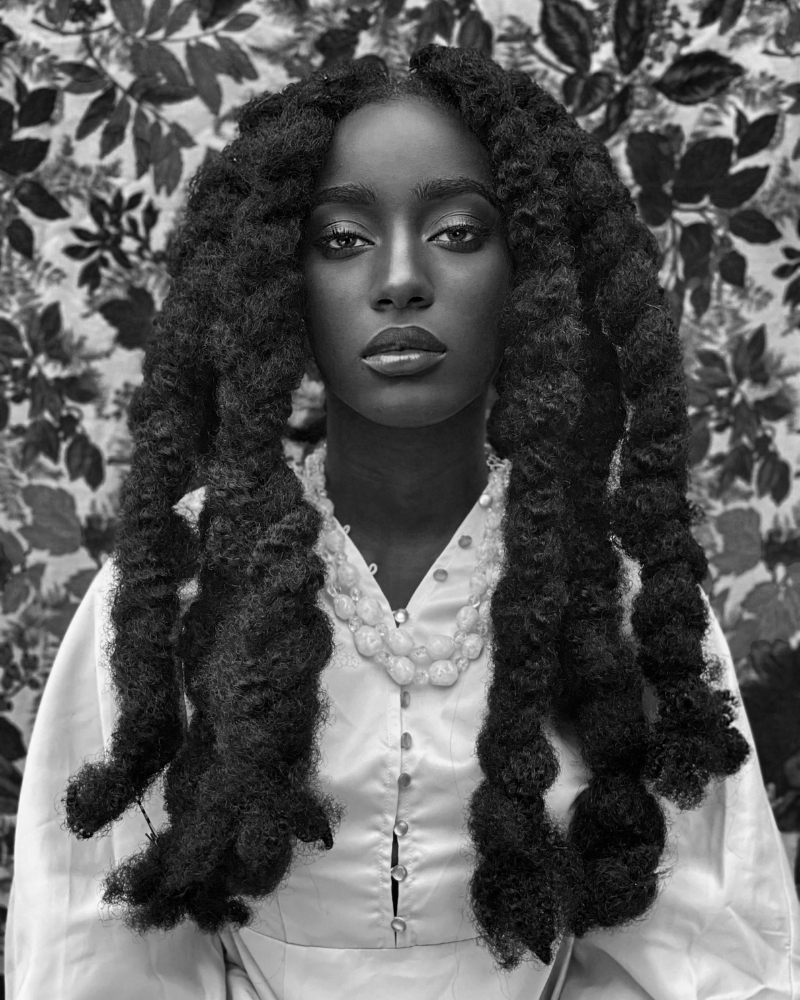

Q: In Art History Too, you’ve described the work as not about “filling in a gap” but about “reframing the conversation.” What does reframing mean to you, and how do these images challenge the boundaries of the traditional canon?

TJ: Reframing begins with the gaze—who’s being seen, and who’s looking back.

The portraits in Art History Too are my family—my daughters, my mother, my aunts—looking back from the walls of spaces that rarely reflected them. I’m not filling a gap in art history. I’m shifting who gets to look you in the eye.

Frederick Douglass understood the power of controlling his own image. I follow that lineage. These photographs don’t “add” to the canon—they reveal how narrow it has always been. We’re not additions to the conversation. We are the conversation.

Reframing means we’re not waiting for permission to be included. We’re creating the frame, setting the terms with intention. The traditional canon never included us by design. So we don’t respect those boundaries—we redefine them.

Q: The series draws inspiration from early photographic processes and from your grandmother’s photo albums, which you call your “first museum.” How did those personal archives shape both the visual language and the emotional tone of this work?

TJ: My grandmother’s albums were the first archive I encountered—a private museum curated in living rooms and shoeboxes. I spent hours turning their fragile pages, studying faces of people I’d never met, revering images that felt as delicate as butterflies.

Later, when I studied daguerreotype, tintype, and wet-plate photography, I realized I was drawn to the same fragility and weight. That reverence carried forward. Without knowing it, I’d been recreating her albums—building my own continuation of that legacy.

Those portraits carry intimacy and permanence. They show what my grandmother’s albums held privately—our joy, our smiles, our everyday selves—and extend them into public history.

I now work digitally for health and environmental reasons, but the emotional tone remains the same. Photography, for me, is a way of extending her legacy forward—holding space for those who came before and those still to come.

Q: You’ve said these portraits are not just images but “proof of presence”—that “we were here, that we are here.” How do you see photography functioning as both evidence and affirmation of Black life?

TJ: Photography holds our honor, our dignity, our truth. It is witness.

For me, it records our wholeness—joy and struggle, intimacy and determination—without asking permission to exist. Each portrait becomes evidence: evidence of love, of connection, of lives lived with intention and grace.

This is what proof of presence means. We matter enough to be remembered. We matter enough to be seen—on our own terms.

Q: You’ve emphasized that visibility is not a luxury but a right. In what ways do you hope Art History Too encourages viewers to reconsider the politics of visibility and who is remembered within art history?

TJ: Visibility is not a luxury. It’s not a favor. It’s a right.

For too long, Black presence in museums and textbooks has been treated as an exception or a token. Art History Too rejects that logic. These portraits insist our stories are central. We aren’t guests in art history—we are its authors.

Look at who fills museums. Look at whose names are remembered. Then look at who’s missing. We’ve been here all along—creating, loving, living lives worth remembering.

I want the next generation to grow up assuming what should have always been obvious: our presence is permanent. I want curricula that center Black women’s perspectives from day one, and gallery walls that reflect the true diversity of this country.

We’re not waiting for inclusion anymore. We’re taking our place.

Q: Finally, has being recognized as a Critical Mass Top 50 artist opened new opportunities for you—whether immediately following the honor or over the longer term?

TJ: Yes. One hundred percent yes.

Since receiving the honor, I’ve been awarded a grant, featured in articles, invited to exhibit in New York, and even learned my work was being studied in a university classroom. The professor used Testify as a teaching tool.

These opportunities matter. They put my work in rooms where decisions get made. They accelerate momentum—what I thought might happen years down the line has already begun.

Recognition creates momentum. One opportunity sparks the next.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Shane Hallinan: The 2025 Salon Jane Award WinnerFebruary 12th, 2026

-

Greg Constantine: 7 Doors: An American GulagJanuary 17th, 2026

-

Yorgos Efthymiadis: The James and Audrey Foster Prize 2025 WinnerJanuary 2nd, 2026

-

Arnold Newman Prize: C. Rose Smith: Scenes of Self: Redressing PatriarchyNovember 24th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Cathy Cone (2023) and Takeisha Jefferson (2024)October 1st, 2025