CENTER’s Curator’s Choice Award Second Place Winner: Jeffrey Heyne

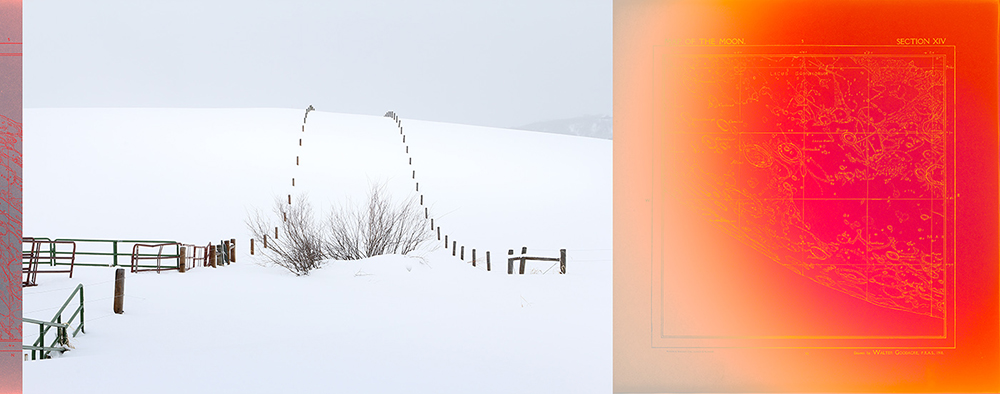

©Jeffrey Heyne, Contour Map with Cattle Fence and Silver Spur, 14” x 39” , 1971/2016, Prior to the Apollo landings, NASA cartographers produced contour gradient maps superimposed over satellite photos. NASA artists then created black & white gouache paintings depicting the lunar landscape as it would be anticipated by the astronauts’ point of view from the lunar surface. Silver Spur peak was a landmark feature that helped orient the astronauts. During summertime, I was not really aware of the cattle fences as they just blended in with the sage and scrub of the arid landscape. But not so during winter. Barbed wire, split rail, and electric fences etch dark lines that roll for miles through the stark white snow covered grazing lands. They clearly make evident boundary lines parsing up the landscape, defining property and land ownership—all backed by a deed on paper of a legal construct but very abstract to the native peoples of just a 120 years ago.

Congratulations to Jeffrey Heyne for his second place selection in CENTER’s Curator’s Choice Awards for his project, To Hunt a Moon. The Choice Awards recognize outstanding photographers working in all processes and subject matter and the winners receive recognition via exhibition, publication, admission to Review Santa Fe portfolio reviews and more.

Juror Lisa Hostetler, PhD, Curator-in-Charge, George Eastman Museums shares her thoughts on her selection:

As usual with CENTER awards, there were a number of strong submissions that made selecting the finalists difficult. The ones that I chose seemed to me to be the most effective combinations of concept and form; in other words, the idea for the project and its execution were equally matched in quality and originality. It was a coincidence that the three projects all had to do with the role that photographs play in constructing ethnic, political, and national history, but the fact that materiality is an important factor in each is not. Although images on screens are increasingly important in today’s culture (and, I believe, valid as an art form), my knowing that works by the photographers would be exhibited in physical space drove me to pay particular attention to the submitters’ notes about the images’ final form. I felt that the finalists had a solid vision about the presentation of their work, as well as its concept and images.

The second place project, “To Hunt a Moon,” also refers to a discomfiting event in US history—the 1898 Ute journey from their reservation to their ancestral home in Colorado for a month-long hunt. Although following ancient tradition, the indigenous people’s hunt violated state wildlife protection laws, and the army was deployed, eventually resulting in the Utes’ retreat. The works in the series poetically juxtapose images from the terrain the Ute traveled and lunar landscapes, along with maps showing their route.

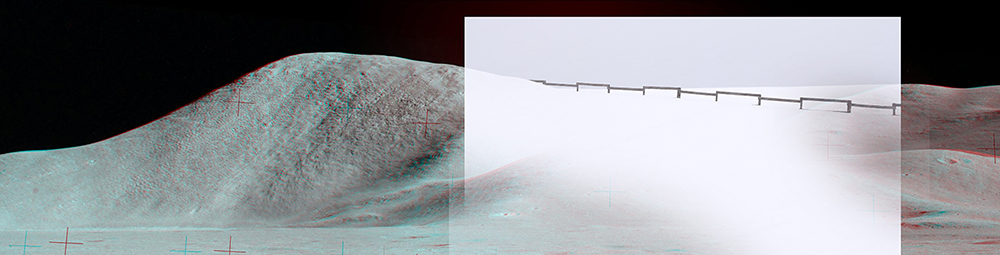

©Jeffrey Heyne, Mt. Hadley Anaglyph Pan with Fence and Snow Storm 14” x 55” 1971/2016 This 3D stereoscopic NASA photo from Apollo 15 is a stitched together panorama of multiple photos. After capturing a series of photos, the astronaut would step a few feet to one side and re-take another series of photos of the same scene. After processing back at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, lab technicians would apply red color to the left hand photos, and cyan to the right hand photos. By viewing the completed image through color filtered eye glasses, a three-dimensional view could be imparted. About 20% of the Apollo photos were captured this way.

Lisa Hostetler, PhD, Curator-in-Charge, George Eastman Museum

Prior to the Eastman Museum she was the McEvoy Family Curator of Photography at the Smithsonian American Art Museum and curator of photography at the Milwaukee Art Museum for seven years. Before her position in Milwaukee, Hostetler was a research associate in the photography department at the Met.

©Jeffrey Heyne, Electric Fences and Swann Range, 14” x 23”, 1971/2016, Most treaties with Native Americans are broken due to pressures in exploiting land resources be it minerals, agriculture, grazing, or the expansionist doctrine of Manifest Destiny. Today this is being tested in the heavens. Ratified by 105 nations, The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 declares governments cannot claim sovereignty over any celestial body such as a planet or the Moon. Yet in 2015 the United States signed the U.S. Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act. It gives private companies in space the right to extract minerals for commercial purposes, yet not claim any territory. The corporations Planetary Resources and Deep Space Industries are now developing robotic missions to the Moon and asteroids to mine for minerals. With inevitable boundary disputes, many legal experts believe this Act could be the first step in violating the 1967 Outer Space Treaty.

Jeffrey Heyne was launched three years after Sputnik, bought his first camera when eight, practices architecture sometime, and imagines photographic stories all the time. His various bodies of work are a search for narrative based on subtextual readings of seemingly disparate images and concepts. Be it images of Barbie dolls manipulated into normal human proportions, freeze-framed Muybridge photos made to be moving again, or iconic neo-classical and Renaissance paintings of the female form seen through a colored veil of the male gaze.

His extensive series “To Hunt a Moon” explores a narrative of land ownership centered on the native peoples of the West, cattle ranches, the fledgling statehood of Colorado, and the new frontier opened up by the Apollo Moon missions.

Jeffrey Heyne has exhibited his photography for more than twenty five years throughout the country and is represented in the collections of the Fort Wayne Museum of Art, Boston Athenæum, Boston Public Library, Fidelity Investments, Boston Properties, Marriott, and Compaq Computers. In April of this year his “To Hunt a Moon” series was awarded the Juror’s Award from the Fort Wayne Museum of Art, and week later he was selected for 2nd Place and awarded the Museum purchase prize. Last year the same series received the Hamedah Glasgow Director’s Award from The Center for Fine Art Photography in Fort Collins, CO. In 2003 he was honored with a Barbara Singer Award for artists exploring new media. His work has been represented by Studio Soto at the 2007 Iberoamerican Art Fair in Caracas Venezuela, NK Gallery, and currently 555 Gallery. In 2008 his Madison Ave. Mannequin Series was featured in Columbia Picture’s movie, 21, the story of MIT students cheating the Las Vegas blackjack tables. His makes his home and studio in Fort Point, Boston. More info can be found at www.unit35.com and followed on Instagram @jeffrey_heyne

©Jeffrey Heyne, Flag with Power Pole and Mt. Hadley, 14” x 39”, 1971/2016, The pairing of the American flag with the utility pole seem to acknowledge one another in that they both convey power—actual and symbolic.

To Hunt A Moon

To Hunt A Moon grew out of a chance encounter with Bill, a ranch owner in Steamboat Springs. In 2015 I was photographing in the middle of a large ranch capturing the summer evening light. I thought I was the only one around for miles except for some cattle and hay bales. A mile away I see an old fellow limping towards me. After 30 minutes he approaches, takes off his cowboy hat, and I can see his face is deeply creviced and darkly tanned from being outdoors his entire 70 years. He asks me if I am taking photos, if I realize I’m trespassing, and if I consider myself a kind soul. I slowly answered yes three times.

I quickly came to realize he was just toying with me, but in an eloquent and philosophical manner, and we strike up a friendship after just a few minutes. The following winter I visited again to photograph his ranch. But this time the stark white snow covered landscape reminded me of the Apollo astronaut photos from the Moon. There, the overwhelming brightness of the Sun makes the powdery lunar surface resemble snow.

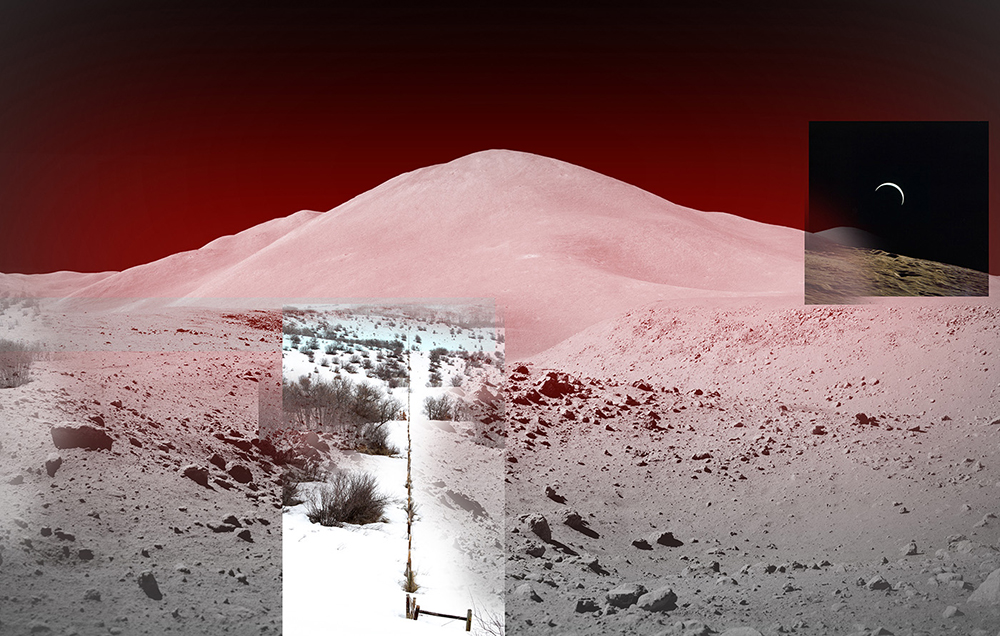

©Jeffrey Heyne, Silver Spur Pan and Grazing Pasture after Passing Storm, 14” x 46”, 1971/2016, Composed of five telephoto images stitched together, the name of step-like mountain peak formation was coined by the Apollo 15 astronauts. The hill line of the snow covered grazing pasture blended naturally with the ridge line of Silver Spur. This was one of my initial collages of Moon photos with snow covered ranch photos.

On Bill’s ranch, the contrast of the dark cattle fencing against the white snow is very apparent and I’m intrigued with the way property is parsed up—especially since the region was once occupied by the Ute Indian Tribes. While undertaking research on the region, I came across an1898 newspaper story about the US Army being called in to prevent a Ute hunting party from taking game around Steamboat Springs. According to the newspaper, the Ute travelled from their Utah reservation determined “…to hunt a moon,” or a month long period. The Ute hunting party conferred, and with the intimidating threat of US soldiers looming, the Ute acquiesced and were escorted under armed guard back to their reservation. After almost 5,000 moons, this was probably the Ute’s last hunting party on their native lands.

©Jeffrey Heyne, North Massif and Pleasant Valley Ranch, 14” x 188”, 1971/2018 [triptych], During a passing heavy snow squall, I rotated my tripod mounted camera for a 400 degree sweeping panorama of Pleasant Vally Ranch. A few miles behind the wooded foothill and rising up 2800” and obscured by the snow storm, is the Continental Divide. One broken treaty came as a result of misunderstanding boundaries. To the Utes, the meandering Continental Divide was understood as the eastern limit of their lands. But the legal boundary written by the US Government, set the boundary on a longitudinal line. This was an abstract concept that made no sense. Why would a property line run up and down mountains, across rivers, and cut in half alpine grazing meadows?

The phrase “to hunt a moon” was my spark. This metaphor for time and the Apollo missions of exploring and conquering of new worlds launched my thinking of a dialog through pairing and collaging my snowy ranch photos with the Apollo Moon photos.

Along with my ranch photos, I’ve sourced vintage moon map engravings by Walter Goodacre published just a few years after the repelled 1898 hunting party, accessed NASA’s 1960’s moon cartography files, and poured over NASA’s Apollo astronaut photo archives from 1969-1972.

©Two Soldiers Stereo Card with Pasture in Snow Storm, 14” x 21” , c:1880’s/2017, While the federal government’s Bureau of Indian Affairs appointed Indian Agents to manage relationships between Indians and the local white population, they proved ineffectual. Some Agents were operating as kleptocrats, but many were there with noble intentions of helping guide the Utes to assimilate into an agricultural lifestyle—which meant to be more like the white pioneers. Strong resistance from the local white settlers and miners often overruled the Agents by citing Washington had no right to tell them what to do on their lands while the “savages” were stirring up trouble. In fact, it was often the local settlers who artificially created tensions to provoke the Ute into retaliation and forcibly defend their Indian lands. This ruse was used by the state governors to demand the Federal government send in the US Army and forcibly push the Utes further away and shrink their territory.

Of the images I selected, I’ve arranged, grouped, and collaged them together looking to meld the form and contours of the lunar topography with the snow covered hills and cattle pastures around Steamboat Springs. Purposeful color shifts and imprints of fencing straddle and blur the line between the terrestrial and the lunar.

Barbed wire, split rail, and electric fences etch dark lines that roll for miles through the stark white snow-covered grazing lands around Steamboat Springs. They clearly define the property boundaries parsing up the landscape that demarcate land ownership—all backed by a deed on paper—a legal construct very abstract to the native peoples of just a 120 years ago. Why were the Ute not being allowed on the lands where they always hunted?

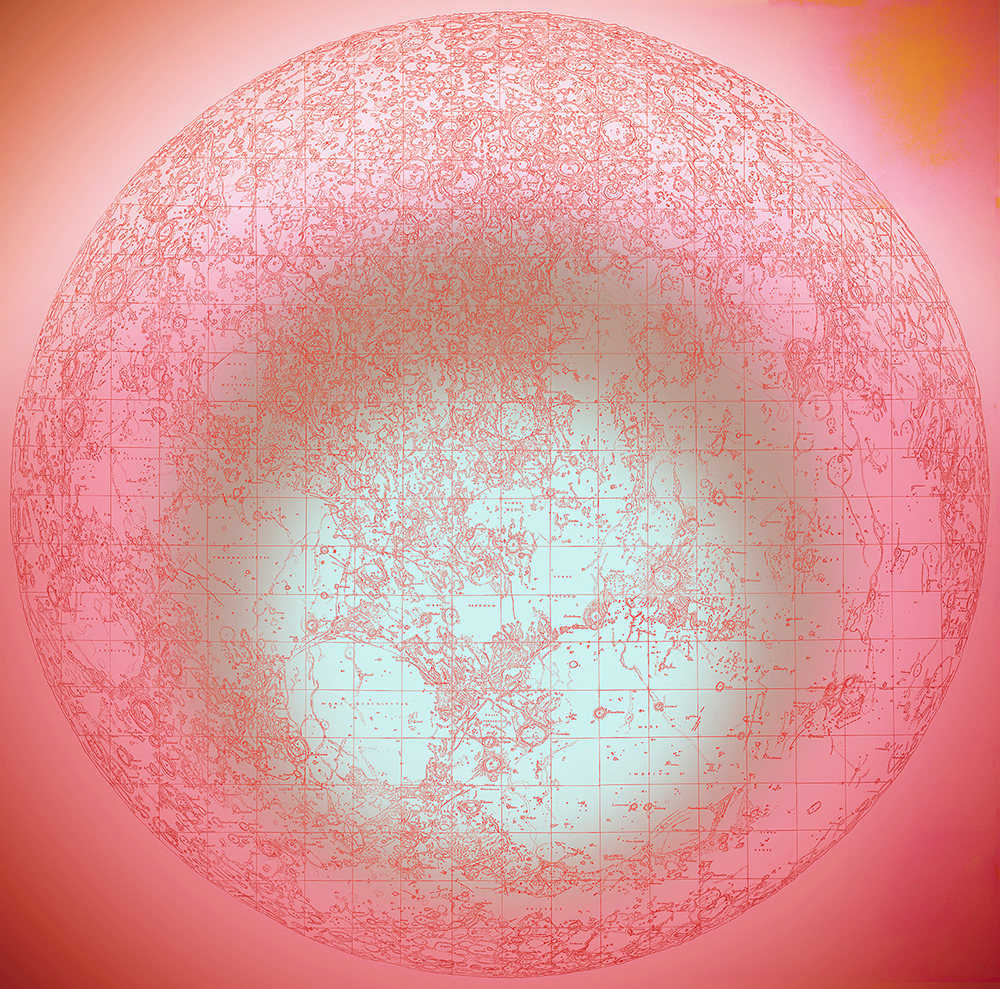

©Jeffrey Heyne, Goodacre’s Moon Map, 36” x 36”, 1910/2017, The British astronomer Walter Goodacre began his Moon observations and drawings just a few years after the repelled Ute hunting party incident of 1898 and then published in 1910. When all twenty-five panels are assembled together, they make for an overall size of six feet in diameter. His map was so lauded for detail and accuracy, it was the resource of reference for any Moon research project for the next fifty years. It was also used by NASA for the initial planning for the Apollo mission landing sites, and where to plant the American flag.

Goodacre’s map was so accurately detailed that it was referenced by NASA fifty years later for the initial planning for the Apollo mission landing sites, and where to plant the American flag.

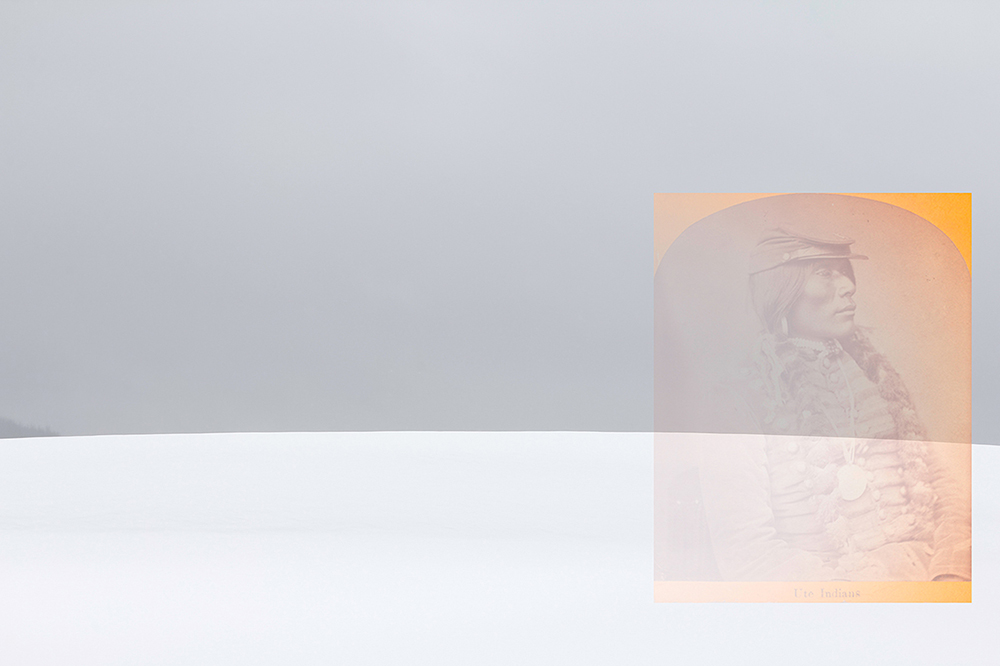

©Jeffrey Heyne, Ute Stereo Card with Pasture in Snow Storm, 14” x 21”, c:1890’s/2017, While the name of this noble looking Ute in this portrait has been lost, it could have been someone associated with Chief Ouray. Ute Chief Ouray was appointed by the US Government to represent the various Ute Tribes in the Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah areas. Ouray was a mix of Mexican and Ute heritage, had command of many languages, including perfect English, lived in a large settlers’ style homestead, and farmed instead of hunting and gathering. He was equally at home with his traditional Ute apparel, as well as wearing the latest Anglo-style fashion. This delighted the local politicians as well as President Grant. Ouray was feted with high level royal treatment in Washington and New York, and with his input, many Ute treaties were established with Ouray’s negotiating skills. The other Ute chiefs back in the West either felt jealous of Ouray, or were angered that he had sold them out. The chiefs gave Ouray a pejorative nickname, Indian Apple, which means “red on the outside, white on the inside.”

©Jeffrey Heyne, Barbed Wire Fence With Half Earth and Damaged Film, 14” x 34”, 1971/2016 Accidental scratches in the film’s wet and soft emulsion while in the processing tank.

©Jeffrey Heyne, Mt. Hadley with Cattle Ranch and St. George Crater, 14” x 72”, 1971/2016, Mt. Hadley is big. It rises up from the lunar mare plain for 12,000 vertical feet in a very a sharp incline. No where on Earth has such an abrupt uplifting of land. In contrast, my collage pairing with Elk River Ranch, there the ridge rises less than 800’. Standing in the powdery regolith next to the lunar lander, one of the Apollo 15 astronauts ruminated while staring up at the mountain six miles away, “…this reminds me of skiing back in Squaw Valley.”

©Jeffrey Heyne, Wessex Cleft with Fence in Snow Storm and Sunstruck Rock, 14” x 44.5”, 1972/2016 , One of my favorite Apollo images is this astronaut walking away. It captures those fleeting matter-of-fact everyday street photography scenes, but framed in such an extraordinary situation. During my week on the cattle ranches in Steamboat, the passing snow storms made for moments of total white-out to then be interrupted with blazing sunlight. And often both occurring at the same time. Sunstruck is a term used by NASA to indicate photograph degradation due to a camera light leak while either on the Moon, back in Houston, or during the wet chemical processing in the photo lab. Usually these accidents resulted in wildly varied colors, which to me seems artistically inspiring. I have purposely applied my own “artificial” wild color accidents to most of my series as an artifact of the technology of the time and the process.

©Jeffrey Heyne, Hadley Rille and Delta with Barbed Wire Fence and Crescent Earth, 14” x 22”, 1971/2016, One of the goals of Apollo 15 was to determine the geological origin of lunar rilles which meander their way across the Moon’s surface. The current thinking is these linear formation are a result of collapsed subterranean lava tubes. Hadley Rille resembles an Olympic snow-boarding half-pipe 3,000 feet across and 1,000 feet deep. The astronauts field trained a very similar sized canyon in Arizona. Photos from these training sessions are comical. The astronauts are walking around with their oxygen back packs, large Hasselblad cameras, and lunar rock sample scoopers, while sporting aviator sunglasses,T-shirts, shorty-short shorts.

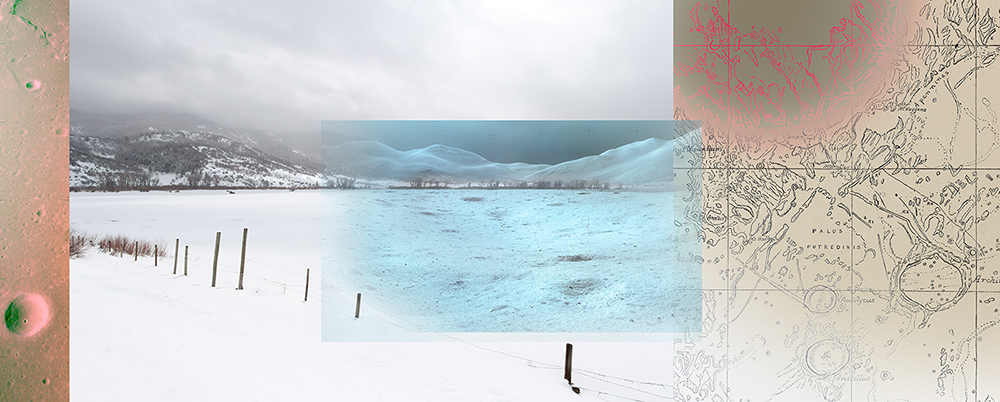

©Jeffrey Heyne, Palus Putredinis from Orbit and Pleasant Valley Ranch with Map, 14” x 35”, 1971/2018, In the middle of this 1500 acre Pleasant Valley Ranch is where Bill caught me trespassing, questioned me, then became my dear friend. A decade ago he and his family where approached by a developer who wished to purchase the valley and adjacent mountain to create a commercial ski resort. Bill and his family declined the offer and instead, enacted a land covenant into the property deed restricting future owners to not develop the land. The ranch can now only be used for grazing and is to be maintained as open space with a natural wildlife habitat along its Yampa River watershed.

©Jeffrey Heyne, Right of Way Fences and Moon Map, 14” x 36” 1971/2016, The grazing pasture is bisected by a right-of-way access to another ranch property beyond the crest of the hill. Early settlers in Colorado were asked to not be alarmed if they say saw large Ute hunting parties passing through their homesteads. The Treaty of 1868 granted the Ute the right to pass through areas off their reservation to access traditional hunting grounds. This relationship proved to be an annual source of friction. Despite protests of Native Americans and conservation groups, in the fall of 2017 the federal government took steps to shrink the size of Bear’s Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in Utah. With four other national monuments also on the list to be reduced, an area the size of Connecticut will become open to mining, logging, and other commercial enterprises.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Arnold Newman Prize: C. Rose Smith: Scenes of Self: Redressing PatriarchyNovember 24th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Cathy Cone (2023) and Takeisha Jefferson (2024)October 1st, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: George Nobechi (2021) and Ingrid Weyland (2022)September 30th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Amy Friend (2019) and Andrew Feiler (2020)September 29th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Jennifer McClure (2017) and JP Terlizzi (2018)September 28th, 2025