Photographers on Photographers: Dan Shepherd on Joseph Minek

This month, we feature our annual August project, Photographers on Photographers, where visual artists interview colleagues they admire. Thank you to all who have participated for their time, energies and for efforts. Today we are happy to share this interview with Dan Shepherd ‘s interview with Joseph Minek. – Aline Smithson and Brennan Booker

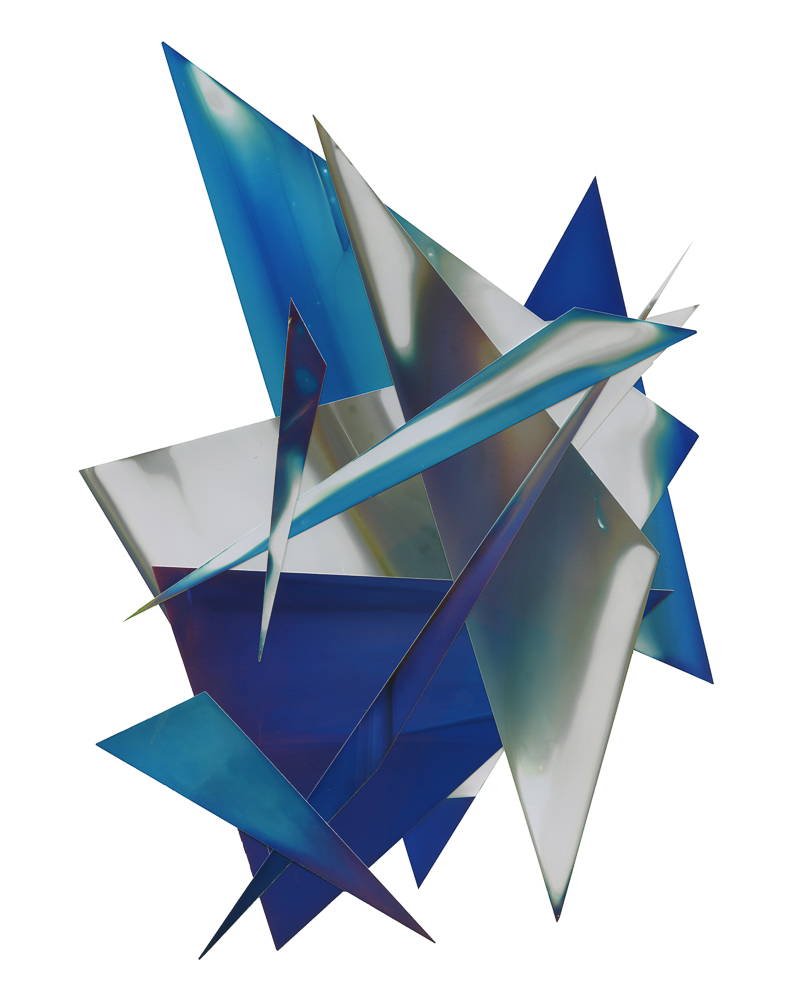

Confession time. I stalk a lot of photographers on Instagram. Some in my official capacity as a gallery owner and others just to pique the image-maker in me. The first time I saw Joseph Minek’s work was on Instagram back in 2016. I had no idea what I was looking at exactly, but I loved the color, geometry and painterly expression. My ‘gram reflex was to look for the #hashtags that would give a clue to process, subject, camera, etc. But Joe’s post descriptions are just the image and the print size with no hashtags. I would later find out that the sparse, ”Let the work speak for itself and make the viewer ask questions” approach is his artistic modus operandi. Both of my Instagram stalker hats loved Joe’s art and I subsequently showed his work at GALLERY 1/1 in 2017 and look for a new show of his work later this Summer.

Joe’s studio practice for nearly a decade has been solely cameraless which is much different than my personal practice, which has been heavily dependent on the camera as my tool of choice. However, my ongoing battle with multiple sclerosis has made the fine motor skills my camera demands a thing of the past. So, for this series I wanted to interview a photographer who has successfully forged an artistic path without the use of a camera.

Joseph Minek is an artist and educator based in Cleveland Ohio. Joseph received his Masters of Fine Arts degree in Photography & Film from Virginia Commonwealth University and his Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in photography from the Cleveland Institute of Art. His work has been exhibited his work in spaces such as the Cleveland Museum of Art, Galerie Kornfeld (Berlin), Gallery 1/1 (San Jose), and Denny Dimin Gallery (New York). Joseph is currently focusing on his studio practice dealing with the possibilities of photographic material.

Joseph Minek is an artist and educator based in Cleveland Ohio. Joseph received his Masters of Fine Arts degree in Photography & Film from Virginia Commonwealth University and his Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in photography from the Cleveland Institute of Art. His work has been exhibited his work in spaces such as the Cleveland Museum of Art, Galerie Kornfeld (Berlin), Gallery 1/1 (San Jose), and Denny Dimin Gallery (New York). Joseph is currently focusing on his studio practice dealing with the possibilities of photographic material.

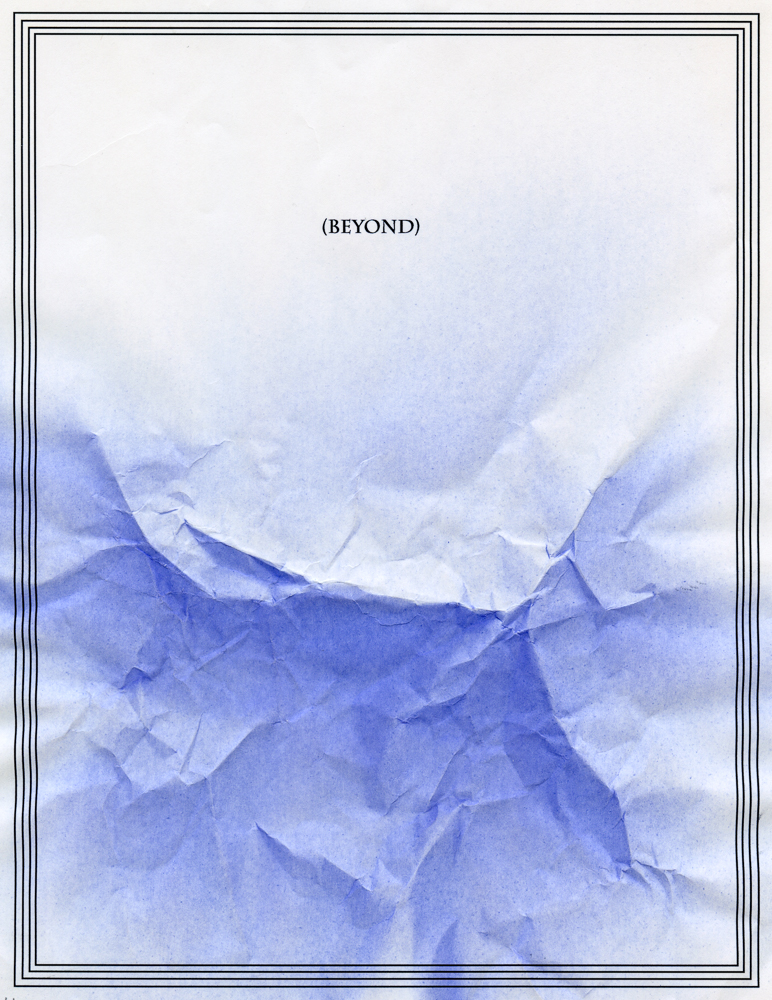

Photographic Works – Artist Statement

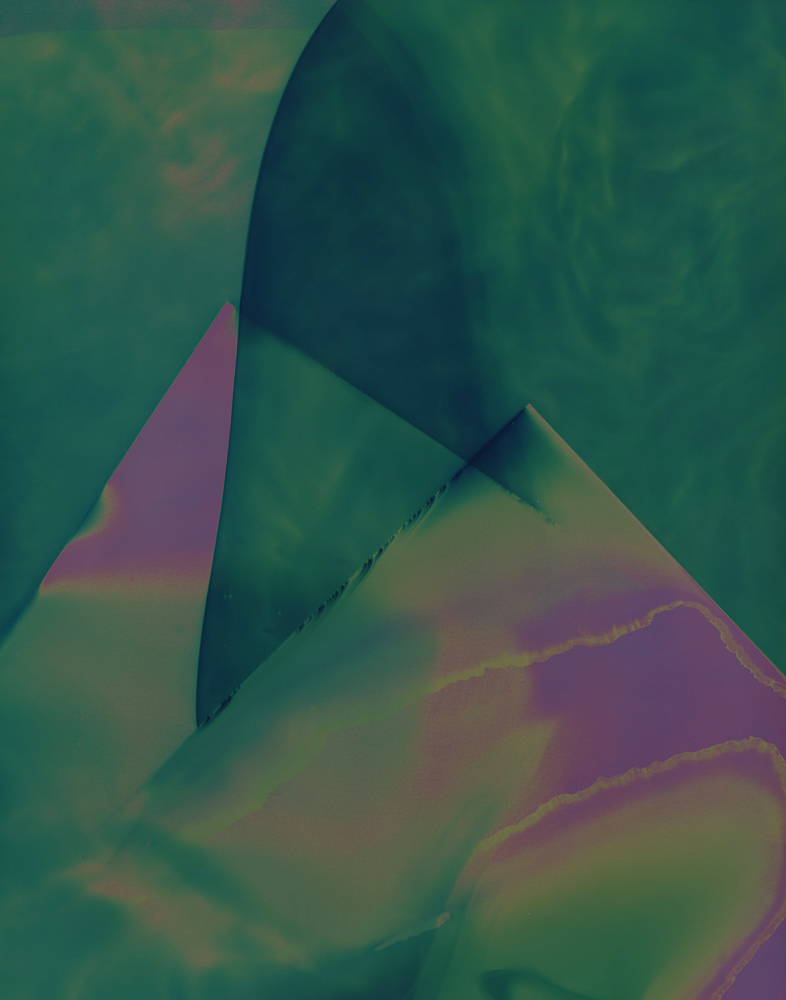

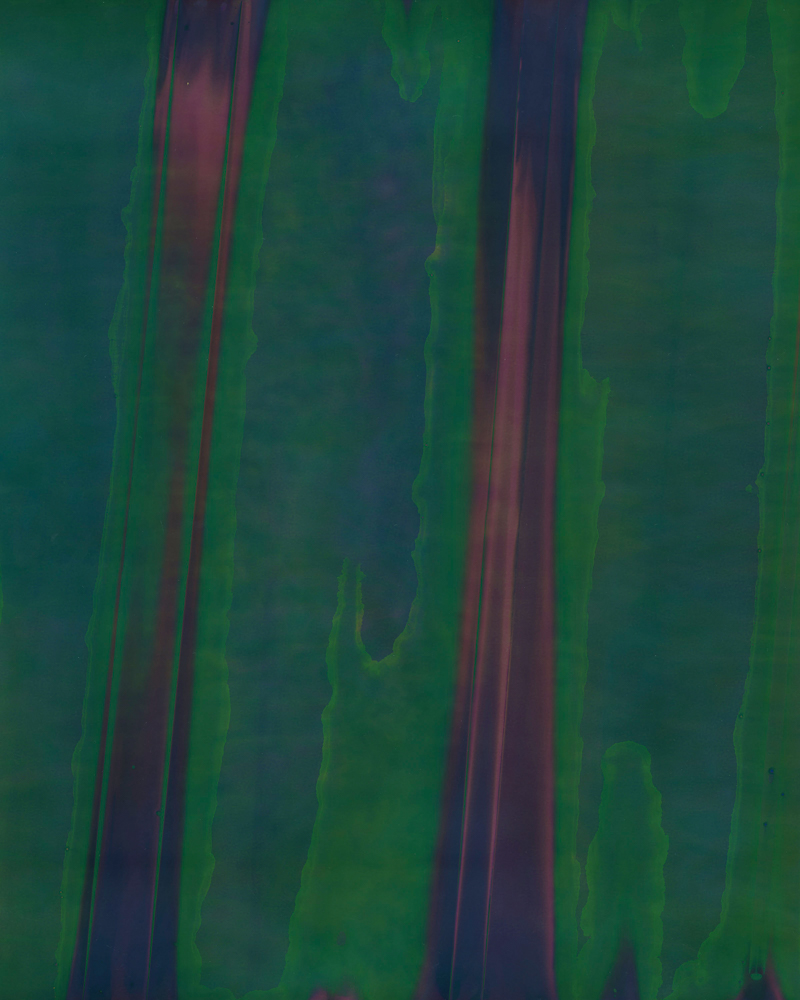

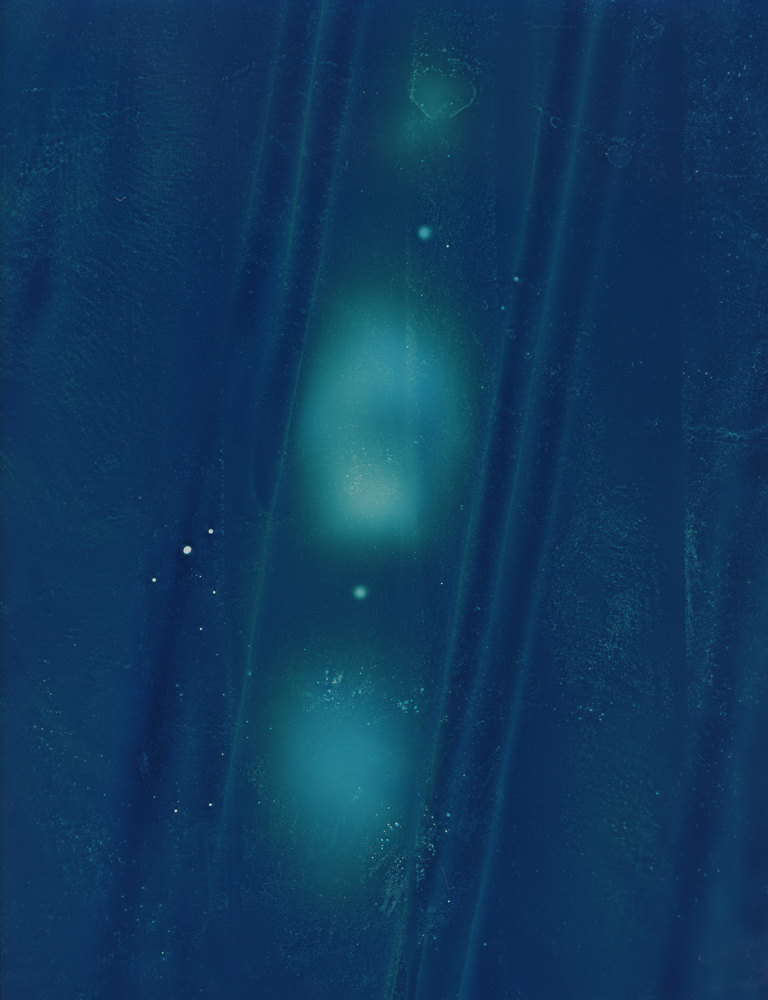

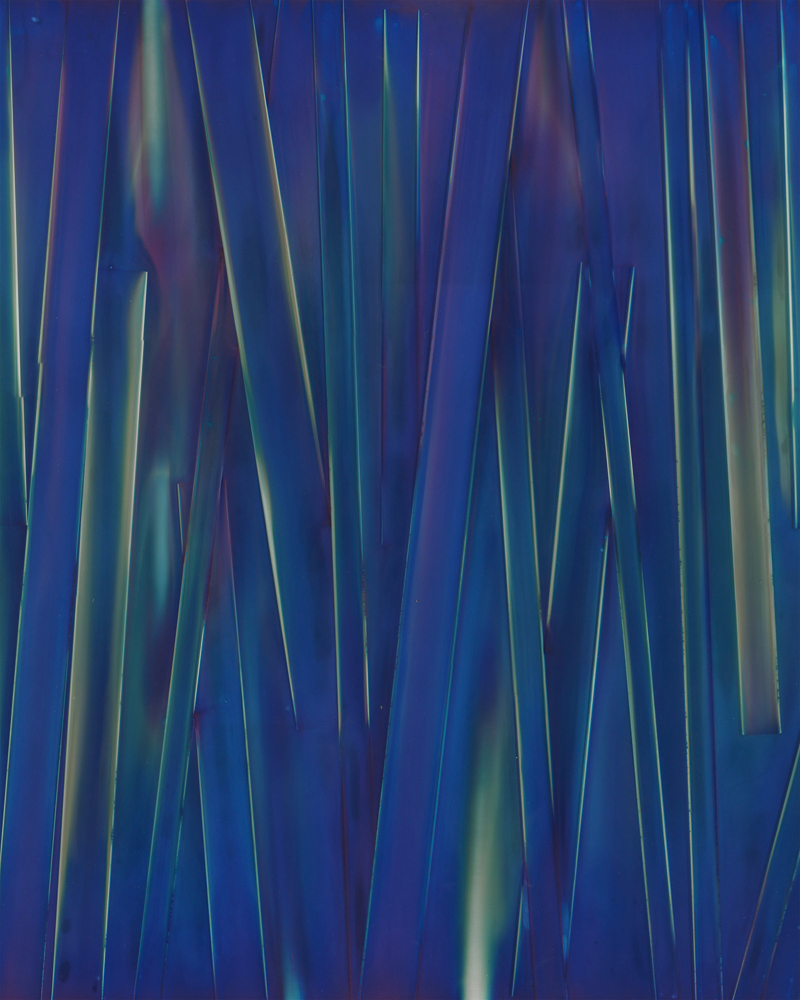

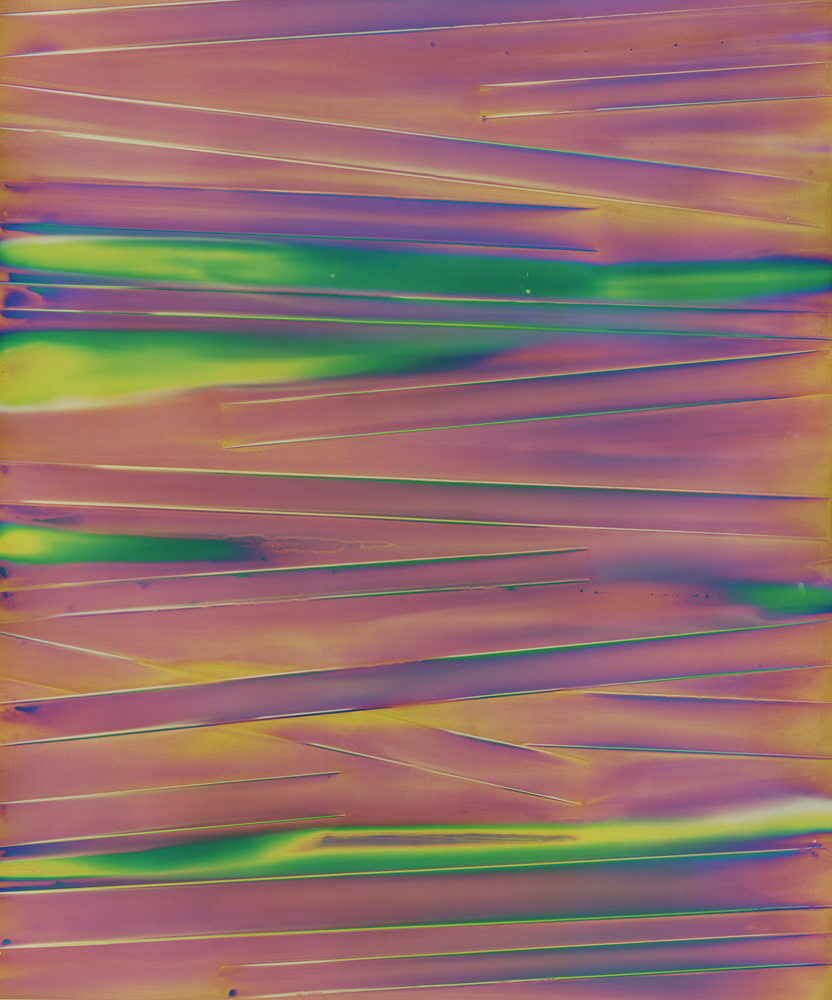

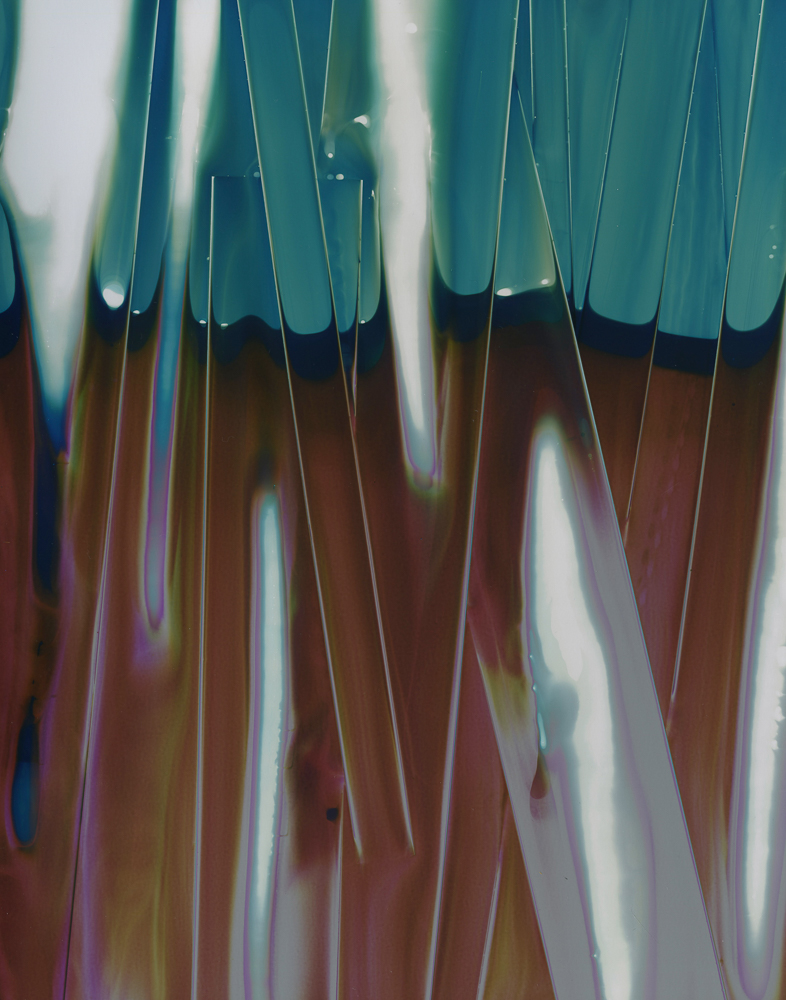

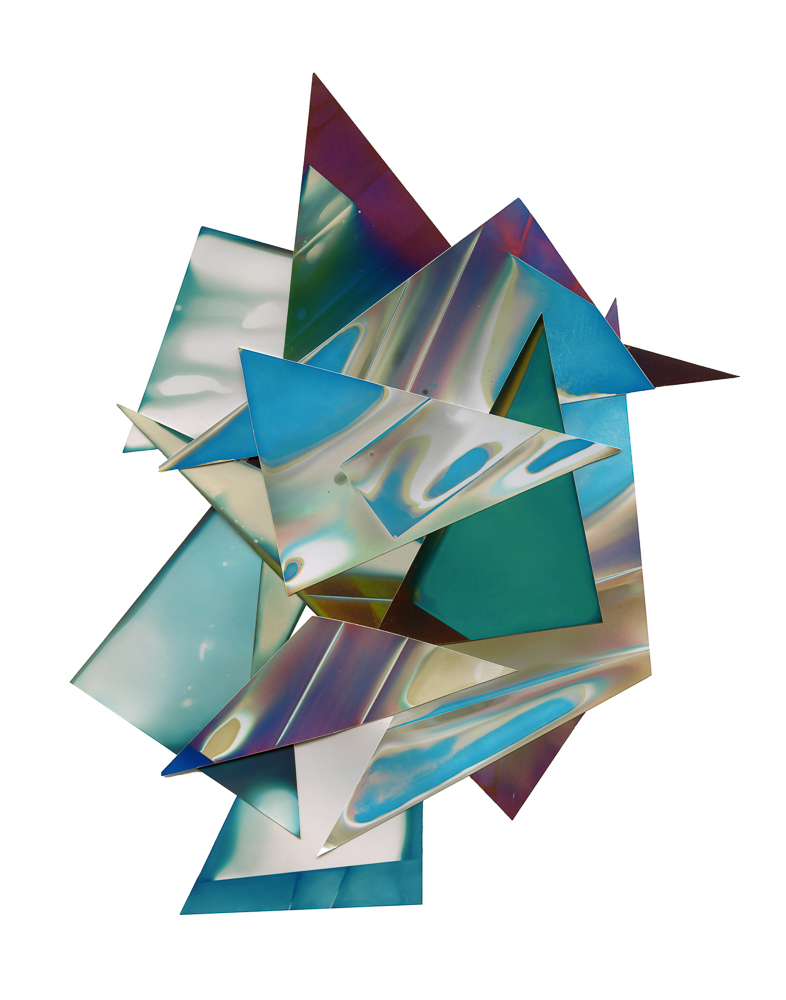

Through a mixture of process art and minimalist abstraction, I question how to depict photography as a self-reflexive entity, not as a conduit to speak of the outside world. Being fascinated by the complex processes used to generate a photographic work, I strip down photography to essentials: light and chemical reactions. Working in a brightly lit darkroom, I expose photographic paper to the space, rendering it useless for its intended purpose. Through various ways of applying photographic chemicals to the exposed paper, I purposefully test the edges of what happens when different parameters are intentionally set beyond their limits. The finished works are luminescent, vivid- colored abstract compositions on glossy, metallic paper that resemble modernist abstract paintings; a deliberate use of aesthetic tropes intended to question it’s making. Lying between confusion and discovery, a conversation about photography’s own making and abstraction begins.

Dan Shepherd: Joe tell me more about how you ended up ditching the camera and embracing your current alternative process?

Joe Minek: In 2009, my last year of undergrad at CIA, I started doing polaroid transfers with burns and mark making. People would see a show of the work and say I was a painter, but I think the work is about photography and that confusion began my interest in the existential dialogue about what is a photograph. Summer 2010, I was playing around with a toy camera that had some slide film in it and one of the slides came out just pure blue. I must have accidentally shot the sky. At that time I was bored with just taking pictures of things. There was nothing I wanted to talk about. Then I decided to burn that medium format slide film as a rebellious act of f*ck photography. I was intrigued by the chemical reaction of the flames and the mark making of the soot. I scanned the manipulated film and made pigment prints. That was the start of my cameraless artistic practice..

DS: You then went off to grad school at VCU. Is that where you found your artistic voice and honed the new methods?

JM: Yes. I don’t have an agenda to be pushed with my work. I’m not trying to convince you of anything. It is what ever you see it as. Undergrad was where the idea of material really interested me more than the representation of stuff. Then I headed straight off to grad school. At VCU I continued with slide film and deconstructing it, then scan it in and make large prints of it. But I was driving me nuts that the print was a generation removed it was not the actual object. My final year of grad school, I went on to actually deconstructing the photo paper. I was mark making on the photo paper similar to Marco Breuer. I would get c-prints made of color fields and then go at them. I liked that the color filed is both the thing and a representation of the thing which is different than a portrait of a person. I liked the idea of merging these two things that can’t really be merged in straight photography. That is when I embraced the unique print with the mark making and all physical labor it took to make a print in the dark room. That is what makes it worthwhile and satisfying compared to just printing from the computer. During a grad school studio tour I was asked by a visiting photographer, “Are you an intellectual?” I replied, “No, I’m just a dude whose f*cking making things.” The physical act of making my work is very rewarding.

DS: You mention Marco Breuer. Do you have other artists that have inspired you?

JM: William Henry Fox Talbot. He sparked it all for me as well as May Ray and other historical experimenters. The way Jessica Eaton approach to color is brilliant. Something that has stuck with me is the story when Talbot was corresponding with Hooker in 1839 about some photogenic drawings of lace. Hooker had showed them to some muslin manufacturers and asked if they thought they were a good representation of lace. The lace makers thought Hooker was trying to fool them and they believed it was actual lace and not a photograph. And thus began the age-old photography dialog about the confusion of truth and representation.

DS: You have such a unique vision and experimental process to the way you make your current body of work. How would you describe it?

JM: I would rather have a conversation about photography than what is in the photograph. I am trying to create this confusion and dialog about photography and photographic material and how that can function to still create a photographic piece of work. Photography itself is the main subject of my work. It relates to the history of photography. The early pioneers were just figuring it out on the fly and that is how my work started too. I was just playing around seeing if I could make something with the leftover paper at the CIA darkroom that had no color processor. The materials are what interest me and the elemental way you can make a photographic image with light sensitivity on paper with a chemical reaction.

DS: I have heard you say that you have to know the rules to be able to break the rules.

JM: I use all the materials in the wrong way. Staring with opening a roll of R4 paper in the studio exposing it to light and wrecking for traditional photography. I asked myself, Can I make a photo on this paper with out a color processor? We had a lot of chemistry and paper lying around at CIA that wasn’t being used anymore and I just started experimenting to see what kind of colors I could make with various chemistry combos. The first six or seven months was just trial and error. The ah hah moment was figuring out what chemistry/paper combinations would give me colors that spoke to me and then I built up a chemistry pallet of colors like a painter might do with pigment.

DS: What I love about this approach is that brings up yet again the idea of representation. These are not pictures of blue, it is blue. And you do it blind because you cant see it until the print is fixed, so you can’t respond to how the colors relate to each other in real time like a painter would.

JM: I like bright colors on shiny metallic paper. Which is funny because I mostly wear gray monochromatic clothes and I am not a particularly bubbly personality. I definitely look like an ink covered skater. So, when people see me standing beside my work like a big print of pink neon color they are a little weirded out. I think it is hilarious. It seems a little subversive to people that I like to make pretty things.

DS: There is no instruction book of recipes you have been given, right? You are creating the chemical combinations and its iterative with lots of trial and error, right?

JM: People often ask how much chance is in my work and I might say 5-10% at most. Things like chemistry temperature, dilutions and timing are elements I am constantly considering and controlling. It is a an ongoing process of experimentation. I have made nearly 1700 prints in the last four years since I started this process. There are lots of failures. All the print names are sequential numbered and only the ones that pass my quality control get shown. (Note: you can see the print number in the titles and the cryptic recipe code of chemistry that Joe used to make each one.)

DS: Do you keep notes and document the chemistry processes you have developed?

JM: Nope. It’s all in my head. I have told some people that I keep notebooks because they can’t believe I wouldn’t, but truth be told I don’t. It’s not a big secret. It just seems like a lot more effort after I have already labored to make the prints.

DS: Where do you see the work heading?

JM: I exclusively use Kodak Endura Metallic paper rolls and I want to go bigger than the 30 x 40 trays I have, but I will need to build a custom system to make my 8 feet long dream prints. I am perfectionist and the high gloss of this paper is easily scratched which drives me crazy. I can be a bit of a control freak when it comes to making the prints

DS: You teach several classes at the Cleveland Institute of Art (CIA, your alma mater) and at a local community college. With such a busy schedule what is an average day like and when do find studio time?

JM: I get up at 4 am and head to the gym for two hours most mornings, then I get into CIA by 7am on both teaching days and studio days. I teach full time so the intensive studio time only really comes in blocks during school breaks. Studio days start with and hour of boring paper cutting and then I make work until about noon. The afternoon will include a nap and often time doing my other love, skateboarding.

DS: At the gallery we have shown the custom designed skateboards based your prints. People really liked them.

JM: Yep, those are made by my friend’s company, Colony Skateboards. I have a really eclectic set of skater friends who would have never be hanging out together, if it were not for skateboarding. I actually picked up a camera to start documenting the group for Colony. It is the first time I have seriously used a camera for a personal project in almost a decade. At first it felt kind of weird. I wondered, “Do I still know how to “take” a photograph?” But it has been a nice change of pace and a fun side project.

DS: Skaters are a tight community and mainstream now. City sanctioned skate parks were not a thing when I was young. That big Sotheby’s auction of the complete set of Supreme deck sold for $800,000 to a 17 year old collector in January. Crazy.

JM: Skateboarding has definitely become a growing cultural influence. Actually, I will be in an up coming show at The Carnegie Center for Art and History in Indiana where all the artists are skaters or influenced by skateboard culture. Blunt: Inspiration in Transition. It runs August 2 through September 28, 2019.

Dan Shepherd was raised in the Pacific Northwest, enjoyed many creative years in New York City, Los Angeles, and Seattle before finding himself based in San Jose. The balance between urban living and love of nature is an ongoing pursuit for him and a universal human theme that drives his artistic practice. When he is not making art, he loves to champion the art of others. Dan is the owner and director of GALLERY 1/1 that specializes in alternative process and experimental photography as well as an occasional Guest Editor for LENSCRATCH – Fine Art Photography Daily and a Contributing Writer for Don’t Take Pictures Magazine. Dan has a Masters in Environmental Science from Columbia University and an International Diploma in Plant Conservation from the Royal Botanic Garden, Kew in England, as well as a BA in Japanese from the University of Oregon.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Ragne Kristine Sigmond: Portraits of Painterly LightDecember 2nd, 2025

-

Mary Pat Reeve: Illuminating the NightDecember 1st, 2025

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025

-

MATERNAL LEGACIES: OUR MOTHERS OURSELVES EXHIBITIONNovember 20th, 2025