Photographers on Photographers: Al J. Thompson in conversation with Rashod Taylor

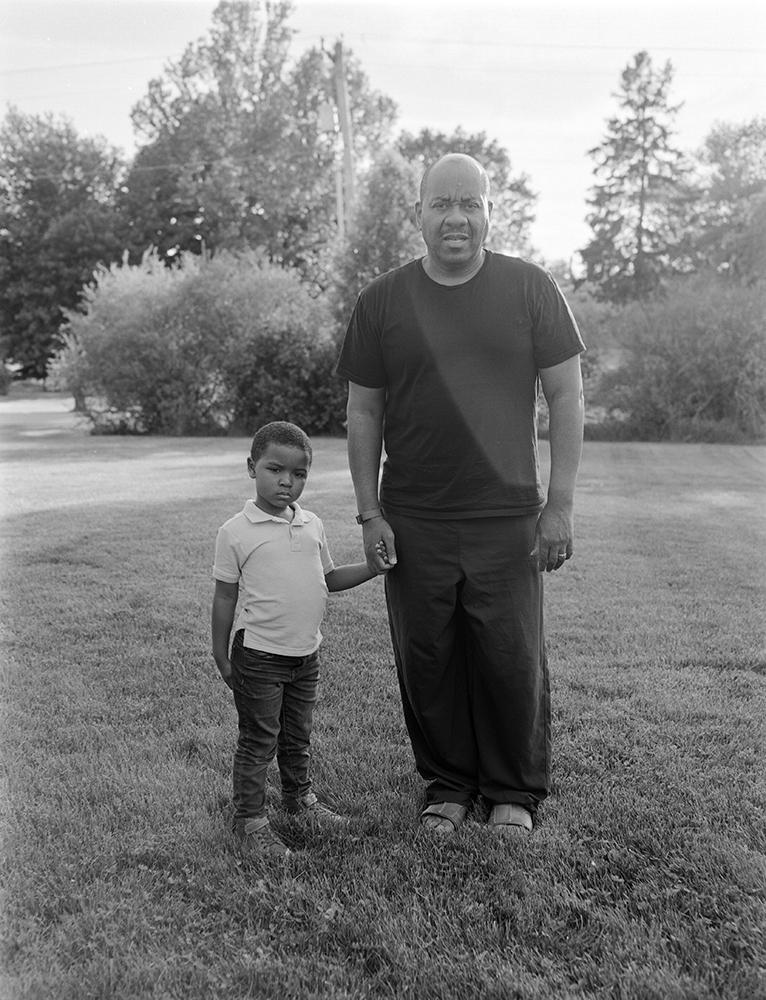

I can intensely recall the Saturday afternoon when I saw what would become my first vehicle. The smell of newness mingled with precision as it trickled up my nostrils. It is a familiar bond, having for the first time, eyeing Rashod Taylor’s poetic photographs of his immediate family—mainly his son. It still feels new, as if he had just stepped out of his dark room scented with chemicals. His images reminded me of my two children, who I’ve been documenting over the years.

Studying his images gave me a sense of calm, floating in the middle of a world that is surrounded by the noises of a pandemic and the second wave of the civil rights movement that was long overdue. His usage of home space directly translates into intimacy, cushioned inside the fabric of our hearts. As the world plows its way into a new era of relearning what has not been taught about people of darker skin; we find comfort in knowing that everyone is connected by degree. In some small [or large] way, Taylor’s photographs spells the importance of family. And as I’m constantly being reminded; it is a necessary dialogue in today’s new world.

Rashod Taylor is a fine art and portrait photographer whose work addresses themes of family, culture, legacy and the black experience. Born and raised in Bloomington, IL Rashod was involved with photography at a young age. Working in his high school darkroom shooting portraits and capturing events for the school newspaper and

Rashod Taylor is a fine art and portrait photographer whose work addresses themes of family, culture, legacy and the black experience. Born and raised in Bloomington, IL Rashod was involved with photography at a young age. Working in his high school darkroom shooting portraits and capturing events for the school newspaper and

yearbook ignited his growing love for photography. He attended Murray State University and received a Bachelor’s degree in Art with a specialization in Fine Art Photography. Since then Rashod’s work has been exhibited and featured in publications and media throughout the Midwest. Most recently his tintype work was included in the “mobile” photography exhibition for the Midwest Chapter of the Society for Photographic Education Conference in Madison, Wisconsin. He has also been a visiting artist at Murray State University. He is currently working on a series called Little Black Boy where he documents his son’s life while examining the Black American experience and

Fatherhood. He currently resides in Bloomington, IL with his wife and son.

Born in the island of Jamaica, Al J. Thompson moved to an immigrant community in suburban New York in the year 1996. Two decades later he noticed the dramatic changes to the place he once knew, projected by what he termed as ‘political figures coiled with greed’.

As a devotee to the science of Psychology and Visual Arts, Thompson sets out to convey the nuances that he believes are circumstances of societal turmoil. His rhythmic approach to photography, at times envelopes people, places, and things that often generates poetic dialogue with subtlety ¬– one that he perceives is consistent to the impression that all things relate.

Thompson has been published in several magazines including PDN, Booooooom, Ain’t-Bad, The New Yorker, National Geographic, C-41, La Vie, Photo Emphasis, Viewfind, Rocket Science, among others.

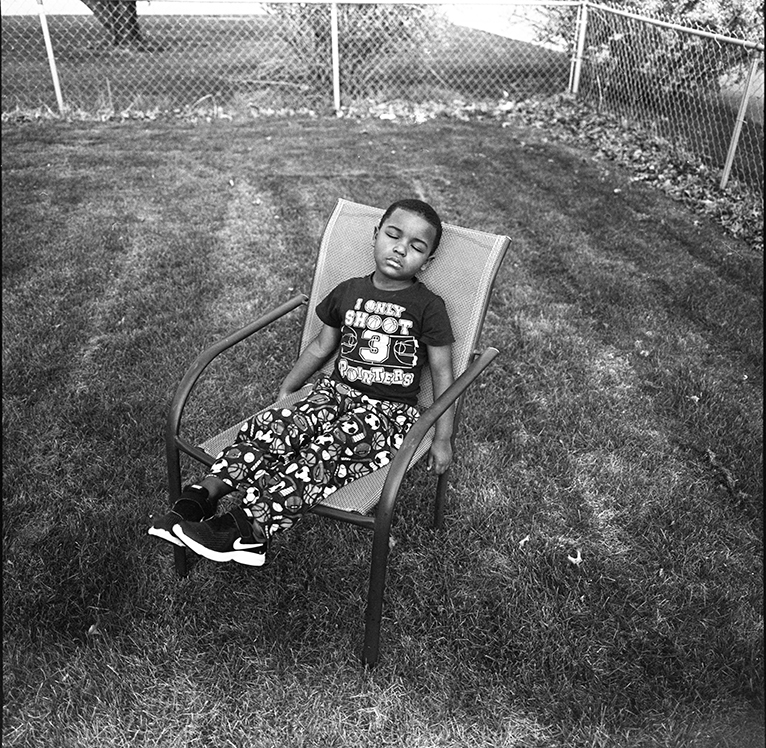

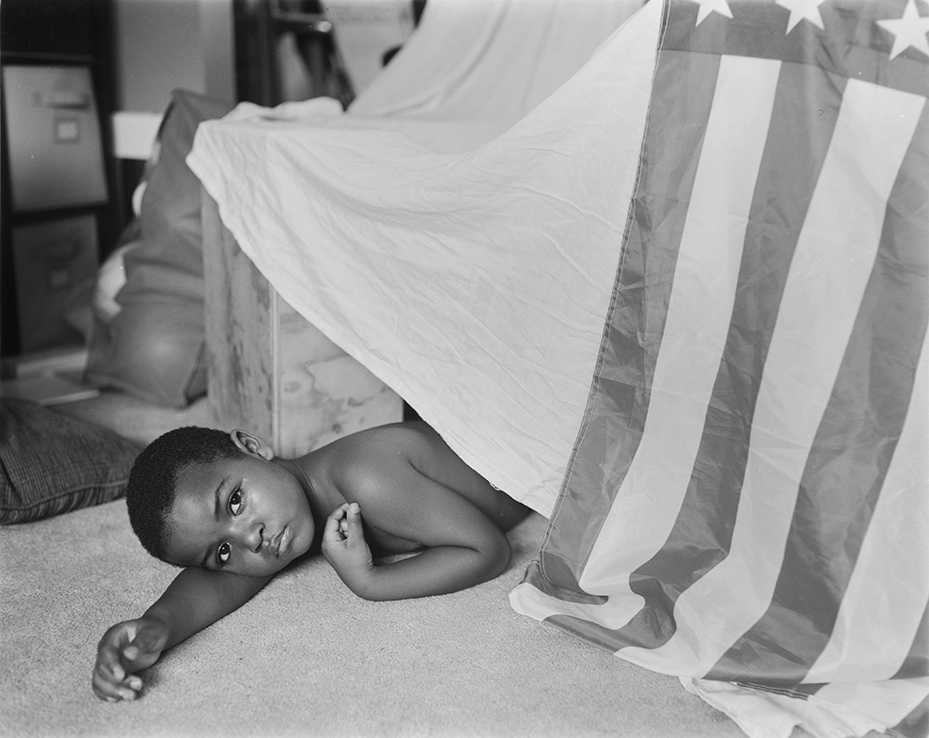

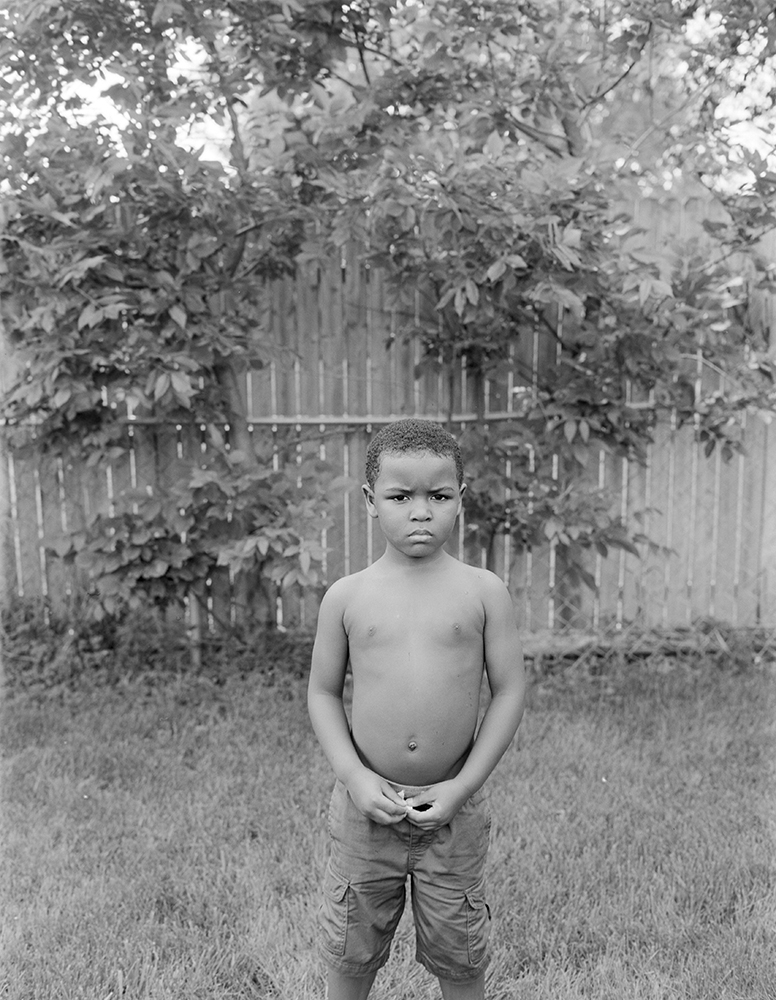

Little Black Boy

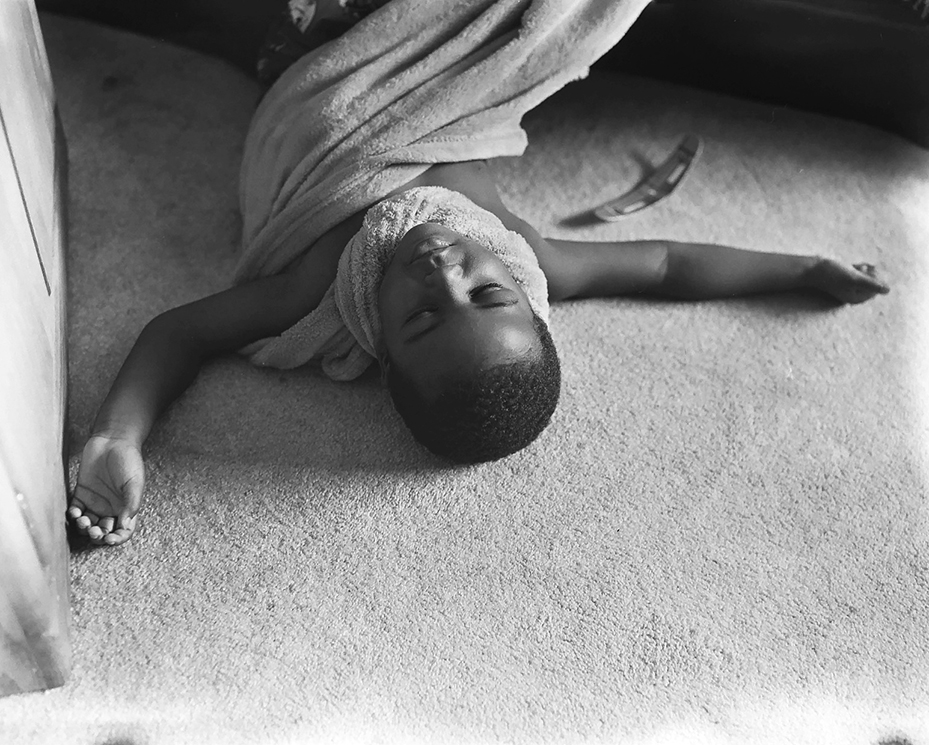

My work addresses themes of race, culture, family, and Legacy and these images are a kind of family album, filled with friends and family, birthdays, vacations, and everyday life. At the same time, these images tell you more than my family story; they’re a window onto the Black American experience. As I document my son I am interested in examining his childhood and the world he navigates. At the same time these images show my own unspoken anxiety and fragility as it pertains to the well-being of my son and fatherhood.

At times I worry if he will be ok as he goes to school or as he plays outside with friends as children do. These feelings are enhanced due to the realities of growing up black in America. He can’t live a carefree childhood as he deserves; there is a weight that comes with his blackness, a weight that he is not ready to bear. It’s my job to bear this weight as I am accustomed to the sorrows and responsibility it brings, the weight of injustice, prejudices, and racism that has been interwoven in our society and institutional systems for hundreds of years. I help him through this journey of childhood as I hope one day this weight will be lifted. – Rashod Taylor

AJT: All these shots of your son…you can make a book out of that! Are you planning on doing so in the near future?

RT: You took the words out of my mouth! I just ran across a book from a friend online on the process of making a photo book. I need to start reading it and doing research but yes I would love to print a photo book of the images of my son. I still have quite a bit of shooting to go in this series but I would love that. I am a sucker for photo books, and I really believe that art in general should be accessible and most photo books check that box.

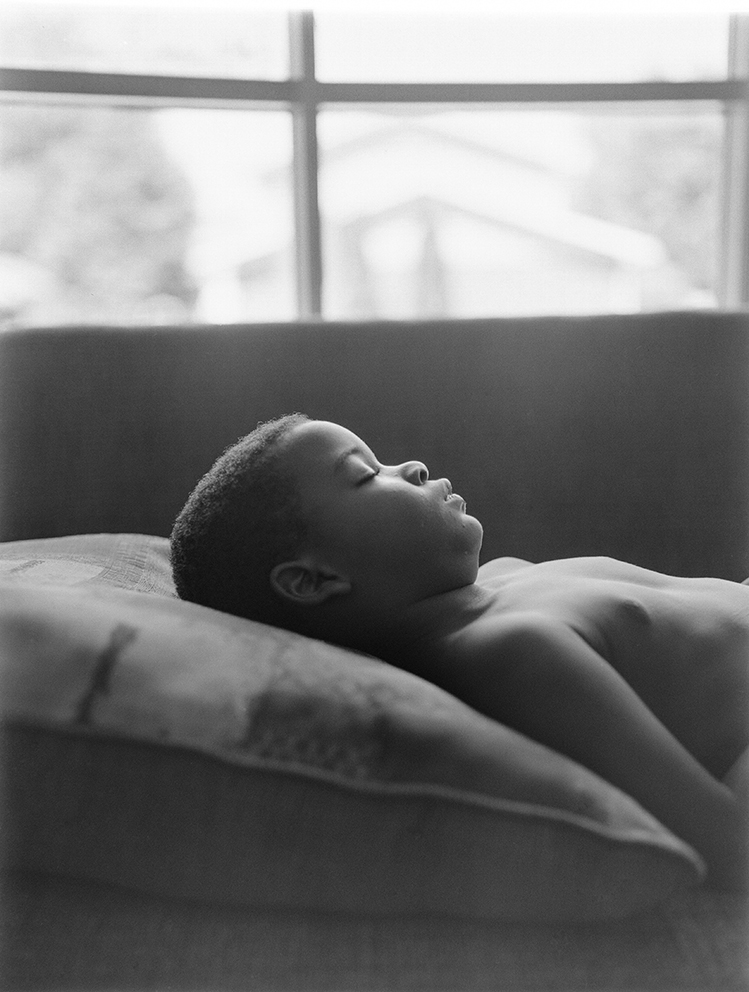

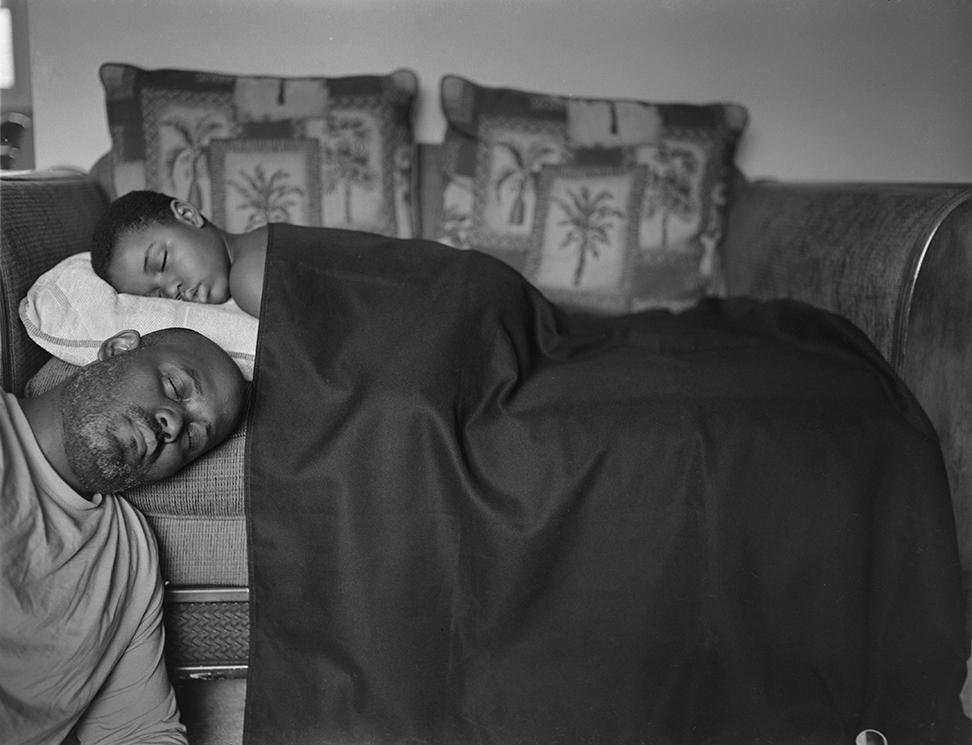

AJT: That shot of your son, presumably sleeping in the couch. It reminds me of a couple of things: Death, in the way it translates the mode in front of the window. But youthfulness, in subject matter. Interpretation can go either way. What were you thinking at the time?

RT: You hit the nail on the head. That image actually has taken me about 2 years to make. I think because of the logistics of getting a four year old to do exactly what you want with large format and secondly me facing my own insecurities. In my mind this image has a duality that I strive to be present in this work. On one hand it shows youthfulness, beauty and peacefulness but on the other side it really shows this post-mortem look of my son. It embodies one of my greatest fears. It speaks to the fragility and vulnerability of being a black father and having the possibility of your child being killed by outside forces whether that be police or people who have a hatred for you because of the color of your skin. You would think that children would be exempt from this type of evil in the world today, but unfortunately they are not. When I see things like Tamir Rice, Ramarley Graham, Antwon Rose, Jordan Edwards and host of other young people unjustly killed by the hands of police I get knots in my stomach and feel like that could have been my son or will be my son. So yeah, this image scares me to death but I needed to face these realities and my own insecurities, which I do through this work. I appreciate your insight on this image, which is one of the reasons, why I enjoy art. People can see different things in the work that they can connect to, which in some cases can be the intent of the artist and in other cases be some new idea that can lead the viewer down another road of meaning.

AJT: I think it’s safe to say that if we take part inside the structures created for us, for better or worse, then all people of various colors have been touched in some form. How have you been personally affected by the ongoing changes pertaining to the topic of race?

RT: I feel like this time is different. I feel like what is happening in the world today is the start of something bigger. The work that is happening to change the very systems and institutions that were made to oppress people that look like me are being challenged and dismantled. That really gives me hope; it gives me hope that things will be better for my son and then his family one day. It also gives me hope that white people are standing with us more, and its not lip service. For this thing to really change we need allies and we need them to stay for the duration. We don’t need any fair weather fans right now as this thing is not going to change overnight. The second part of these recent events have made me tire, and thinking, wow we are still trying to figure this thing out after hundreds of years! With that frustration is something that I feel quite often. I use that frustration as fuel as I make my work, probably more in my other series My America, but we can get to that one next time.

AJT: As artists, we all have end-goals. What do you hope to achieve 20 years from now?

RT: I don’t know if I have an end goal with my art per se. I just know I want to be in a place that I can continue to have the freedom to make the type of work that I want to make and that I am passionate about. Right now I have that luxury and I am extremely grateful to work full time and make work outside of that. But of course as an artist you want the exhibitions, books, gallery representation and so on. Now don’t get me wrong, I do want to be successful in that way (Galleries, Museum’s and publishers feel free to reach out), but the intent of art making for me is an outlet of self-expression. I strive to communicate the things that are important to me in hopes that others can connect to whatever part of these ideas speaks to them. I feel like the place I am now is free from outside pressures to make a certain kind of work or quantity of work. In addition I want to continue to make images that show black people and people of color in a positive light outside of the negative optics that we so often see in the media. There is a false narrative out there that I want to do my part to change. When I look back in 20 or 30 years I want to know I played a small part to getting more art in the world that elevates the depiction of black family life and our black experience into more mainstream thinking and dismantle the deep rooted ideal of black inferiority. In the end as long as I can stay true to myself (my work reflects that), I know opportunities will come around.

AJT: Lastly, this question is more about tools and process than a philosophical one. I see that you shoot with a 35mm, large format, and Wet Plate. Maybe I’m missing more (120 film?). What’s your favorite tool shooting.

RT: I’m a gear head and my wife would tell you I have too many cameras. I have shot withall formats and feel like there is a place for every format, really. 120 has a special place in my heart, however I have recently moved to shooting exclusively in large format. I would love to only shoot 8×10 but I would have to sell all of possessions to do that right now. This series of my son has been shot mostly in 4×5, outside of a few images. I really gravitate to large format because I love the process. It really slows me down and gets me thinking more about light, composition, and connecting with my subject. I also like the formalized nature of it all, when you show up with a large format camera people know you mean business and or have no idea what kind of camera you have. Shooting this way disarms people a little bit when shooting portraits; it can be meditative of sorts.Now shooting large format with my son is totally the opposite of meditative and disarming. Most times when I photograph him it’s a challenge, Imagine telling a 4 year old to sit still for longer than 20 seconds and see how that goes. But it truly is a joy shooting this way and also spending time with my son, teaching him how to use the camera and just having fun with it all. He really gets it now, and sometimes he asks me if Ican take a picture of him when usually it’s me begging and negotiating with him.

For all the gear heads out there; most of these images were shot with an old Graflex Speed Graphic with a 135mm, 4.7 Schneider Xenar lens. I also shoot with an Schneider Super- Angulon 90mm, 5.6 lens for wider shots and a Schneider Symmar-S 210mm, 5.6 for longer portraits. There are a few Mamiya 6 images in the series also. In terms of Film stocks my go to for large format is Illford HP5 and I do my best to hoard as much of it as possible. You remember when everyone was going crazy over toilet paper earlier this year? That’s me with film; I’m that guy with boxes on boxes stashed in the freezer. These days you never know how long your favorite film stock will still be made so I am prepared.

AJT: Haha. Quite relatable with the popular hashtag ‘stay-broke-shoot-film’. And, I don’t mean this as an insult…I have the same problem too. There’s a reward for this kind of dopamine and the memory that it preserves. I mean…it is about chemicals.

RT: I totally agree. I think the reward comes in the ability to continue to do what you love, and to let your voice be heard. Having the tools and resources that I prefer to make the work is very important to me. The idea that the prints and negatives will outlast my son and I, help keeps things in perspective. It’s totally worth the investment and sacrifices I have to make to shoot film, print, and archive them. And not to take anything away from the digital shooters out there, film is just my preference, which fits what I want to do with my art. So yeah! You won’t see me flexing on anyone with a new car, but come check out my darkroom, cameras, and freezer.

AJT: Excellent, Rashod! And on that note, we’ll freeze the conversation here. I truly look forward to seeing your work represented through galleries and publications in the near future.

RT: Thanks so much for the opportunity to share my work and process.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Paccarik Orue: El MuquiDecember 9th, 2025

-

Lauri Gaffin: Moving Still: A Cinematic Life Frame-by-FrameDecember 4th, 2025

-

Dani Tranchesi: Ordinary MiraclesNovember 30th, 2025

-

Art of Documentary Photography: Elliot RossOctober 30th, 2025

-

The Art of Documentary Photography: Carol GuzyOctober 29th, 2025