Flowering in Photography: Mayumi Lake

© Mayumi Lake, Unison (Causality), 2021, Pigment print on canvas, steel, Tyvek, acrylic paint, gold leaf, felt, vinyl, bead, thread, wire, chain, and motor 40 “x 40” x 82”

Can flowers ward off despair? What is it to invest in beauty in the face of fear? Mayumi Lake’s richly-layered sculptural photographic works draw from Japanese traditions that filled prayer sites with mythical flowers during troubled times. As Lake confronts the challenges of navigating two cultures, she creates her own mythical flowers, merging scanned imagery from the kimonos of her homeland with alluring plastic items of American pop culture. The forms of her floral assemblages feel protective and commemorative…bright offerings that honor hybridity and identity as exuberant construction.

© Mayumi Lake, Unison (Resonance), 2021, Pigment print on Canvas, gold leaf, sequins, synthetic hair, and wood 58” x 55” x 1.5”

Mayumi Lake (b. Osaka, Japan) is an interdisciplinary artist, whose work delves into childhood and pubescent dreams, phobia, and desires. She employs herself and others as her models, as well as dolls, toys, weapons, vintage clothes, and altered landscapes as her props.

Mayumi received her MFA in Photography from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She has exhibited nationally and internationally and has published 2 monographs from Nazraeli Press. Her work is in the permanent collections of the Art Institute of Chicago, The Museum of Fine Arts, Huston, Asia Society, Facebook, and more.

A new installation by Mayumi Lake will be permanently on view at Chicago O’Hare Airport Terminal 5 Arrival Corridor in Fall 2022.

Follow Mayumi Lake on Instagram: @deepfriedeast_mayumi

©Mayumi Lake, Unison (Echo) – right, Unison (Reverb) – left, 2021, Pigment print, Pigment print on canvas, resin, beads, gold leaf, fabric, and wood 36” x 53” x 2” each

Driven by my childhood fantasy, phobia, and desire, my artwork interacts with the ideas of time, memory, and floating between the real and imaginary.

I use photography to weave my autobiographical narrative — from the mimicry of prepubescent flesh surrounded by soft pastel clothing, emotionally-charged landscapes with a solitary girl soldier standing, and darkly illuminated and saturated stereotyped females; to bright and sparkly photo-sculptural mythical flowers. I also incorporate sculpture, sound, moving images, and installation to expand my narrative into more complex layers.

As a Japanese immigrant, my work is continually floating/shifting between states: East and West, longing and hope, memories and oblivion, and past and future. I am interested in archiving things that could be forgotten or become obsolete over time — otherwise I will forget where I came from. The awareness of the impermanence of things, or “Mono-No-Aware” in Japanese, has turned into an obsession and obligation to preserve the past as knowledge for the future. The idea of photography works very well to freeze and package the floating moments to archive them.

Although my obsession is rooted in a very personal narrative, I believe that the most personal is the most universal. In this way, I evoke emotional reactions from my viewers.

In Ancient Japan, when political chaos and a series of natural disasters occurred, the people believed the last days of this world were near. To calm their fear and despair, they filled sacred prayer sites with bright and bold images of mythical flowers, believed to bloom throughout the afterlife. Those flowers were called Housouge. The bigger the fear and despair, the more colorful and immense the flowers.

Unison is an ongoing sculptural photographic work, which features my interpretations of the mythical heavenly flowers or Housouge. The blossoms are constructed from motifs scanned directly from vintage girls’ kimonos. They are cut by hand and then reassembled, and include toy parts, plastic flowers, imitation gold, sequins, and various other objects that recall my own childhood in Japan which was saturated with objects that directly referenced American pop culture. The use of the kimono goes beyond being just a reference to my Japanese cultural heritage, it signifies a dying cultural tradition as the use of this traditional garb has all but disappeared and is relegated to a symbolic gesture reserved for special and rare occasions. Elements of the two opposing cultures are intertwined creating a strained and unique harmony illuminated through the constructed blossoms. -Mayumi Lake

©Mayumi Lake, Unison (Pink & Kaleidoscope) , 2021, Pigment print on canvas, acrylic paint, PVC tape, metal, chain, ribbon, plastic, thread, and motor 24” x 84” x 24” each

BC/LL: Creating mythical flowers to ward off fear and despair suggests a belief that flowers possess powers. What powers do you think they have?

ML: I believe that it is not that flowers (Housouge) themselves have power, but that people’s emotions and wishes were sublimated into imaginary flowers. I started to do the Unison project in 2016 and the meaning of this work expanded in me so much over 6 years: from simple fantasy and nostalgia to reflecting on my cultural heritage and self-questioning of the meaning to be an Asian immigrant in this turbulent time.

BC/LL: What do your mythical flowers suggest about the afterlife?

ML: I envision these (my version of) Housouge as blooming between life/death states, like Bardo. I think that is a world where what you see changes completely depending on the individual. For me, I hope it is a place that is both old and nostalgic, yet new and exciting, comfortable, colorful space. I understand that the afterlife is the place you recall your life and prepare to go on to life’s next journey, to be reincarnated.

©Mayumi Lake, Unison (Rainbow Unicorn) 2021, Pigment print, resin, ribbon, pin badge, felt, polyurethane form rubber, and wood 26” x 30” x 5”

BC/LL: Has working with flowers been healing for you?

ML: There are many processes including both digital and analog (physical, hand-oriented processes). It is very hard and time-consuming until the hand cutting is finished, but once I move to the stage of layering hand-cut motifs, it can be very intuitive and therapeutic. This sounds very cheezy but I feel like I am connecting myself to ancient time and the future — like parallel timelines. As a traditionally trained photographer, it is hard and also exciting to turn my work into three-dimensions. Every piece I make/made for this series is full of experiments, and discoveries.

©Mayumi Lake, Unison (Typecasting) , 2020 Pigment print on Canvas, ribbon, fabric, motor, LED light, and wood 42” x 43” x 1.5”

BC/LL: How is photography central to this body of work?

ML: Photography is still my core media and the base of my visual languages. However, this body of work also came out of my frustration about the limitation of the media and my desire to go beyond the limitation of the photographic presentation. Beyond the two-dimensional surfaces and frames, I wanted to add a more physical presence.

©Mayumi Lake, Unison (Decora Kei #2) 2020, Pigment print, gold leaf, resin, synthetic hair, sequin, and wood 32” x 37” x 2”

BC/LL: What can flowers teach us about the past and the present?

ML: Knowing and understanding the past helps us see the future. People’s emotions, karma, despair, hopes, and wishes haven’t changed much a thousand years later. Probably 1000 years into the future, too, even if things/objects do not survive as a form.

©Mayumi Lake, Unison (Gate – You Were Here), 2019 Pigment Ink print, plastic, resin, fabric, bead, seqin, mirror, metal, and wood 36 x 72 x 18

©Mayumi Lake, Unison (Elicitors), 2019, Pigment print, resin, plastic, imitation gold leaf, sequin patch, vinyl, and wood 12’ x 8’ x 2”

©Mayumi Lake, Unison (Nimbus/積乱), 2019, Pigment print on Canvas and backlit film, plastic, gold leaf, fabric, wire, and wood 15’ x 5’ x 2”

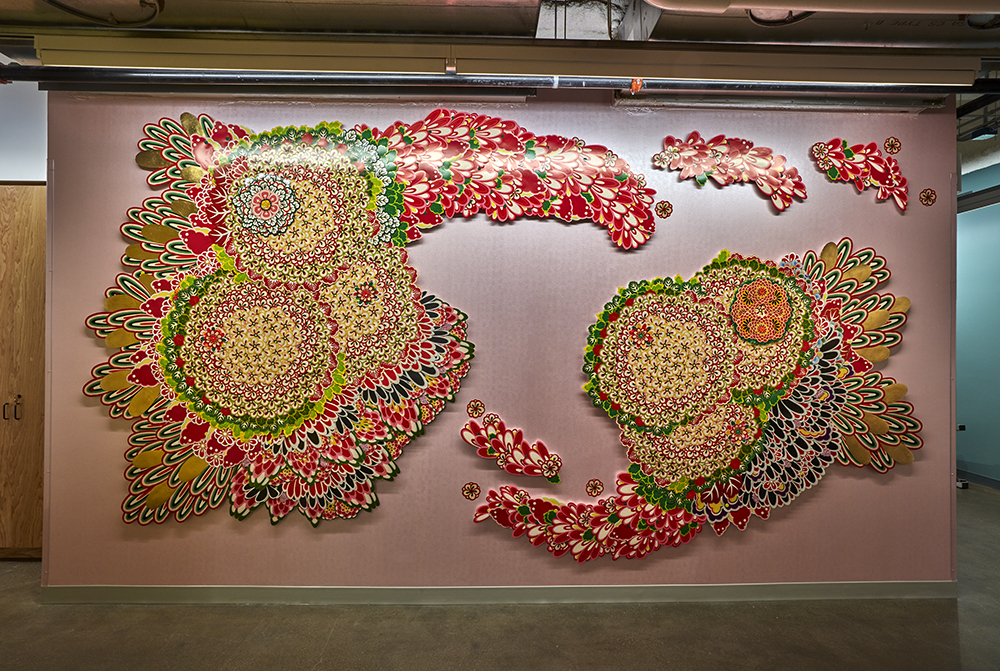

©Mayumi Lake, Unison (Pangea) Front wall, Permanent installation for Facebook Chicago office 2018, Pigment print, resin, plastic, imitation gold leaf, sequin patch, vinyl, silk, pink metallic wall paint, and wood 17’ x 10’ and 8’ x 14’ walls

©Mayumi Lake, Unison (Pangea) Front wall, Permanent installation for Facebook Chicago office 2018, Pigment print, resin, plastic, imitation gold leaf, sequin patch, vinyl, silk, pink metallic wall paint, and wood 17’ x 10’ and 8’ x 14’ walls

©Mayumi Lake, Unison (Amaterasu) 2017, Pigment print, resin, plastic, synthetic hair, imitation gold leaf, wire, and wood 55” x 50” x 4”

©Mayumi Lake, Unison, Installation view, Chicago Artists Collation Bolt Residency Solo show 2017, Pigment print, imitation gold leaf, synthetic fur, synthetic hair, fabric, beads, sequin, wire, wood, mirror ball, motor, LED light, color effect gel, black aluminum foil, USB audio player, and speakers. 15’ x 35’ x 12’ (Space size) Installation video documentation

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The Female Gaze: Alysia Macaulay – Forms Uniquely Her OwnDecember 17th, 2025

-

Bill Armstrong: All A Blur: Photographs from the Infinity SeriesNovember 17th, 2025

-

Robert Rauschenberg at Gemini G.E.LOctober 18th, 2025

-

Erin Shirreff: Permanent DraftsAugust 24th, 2025

-

Shelagh Howard: The Secret KeepersJuly 7th, 2025