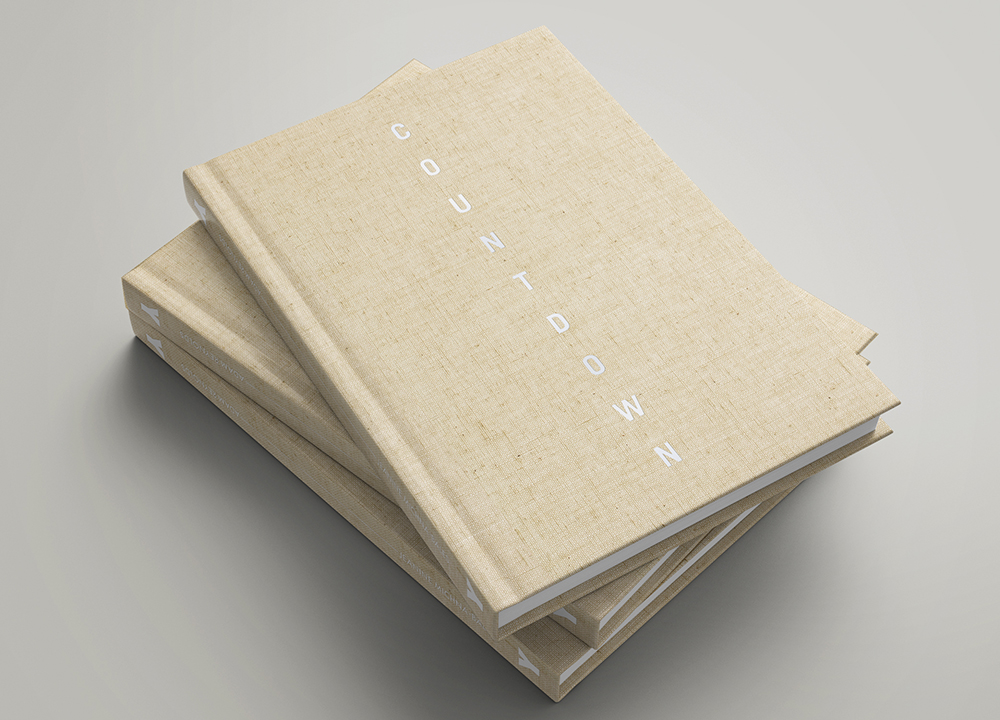

Jeanine Michna-Bales and Adam Reynolds: Countdown

For those of you who may remember the days when your elementary school teacher instructed you in the “Duck and Cover” air raid drill triggered by a lonely siren where you dove under your desk, covered your head with your arms and were instructed not to look out the windows of your classroom, the book, Countdown, should bring back some eerie memories. The book consists of two projects, “Fallout” by Jeanine Michna-Bales and “No Lone Zone” by Adam Reynolds, that focus on two opposing perspectives of the Cold War in the United States: the decidedly defensive posture of retreating to a fallout shelter in hopes one would survive a nuclear attack as depicted in “Fallout” and the coldly impersonal images of nuclear missiles, and the ghosts of crews that manned U.S. missile silos that are now nuclear tourist sites in South Dakota and Arizona as “No Lone Zone” illustrates. Both projects are coldly impersonal with nary a human figure in sight other than their remnants such as an empty whiskey bottle in a fallout shelter and a group photo of the last crew of a missile silo over a red Coke machine in a crew lounge.

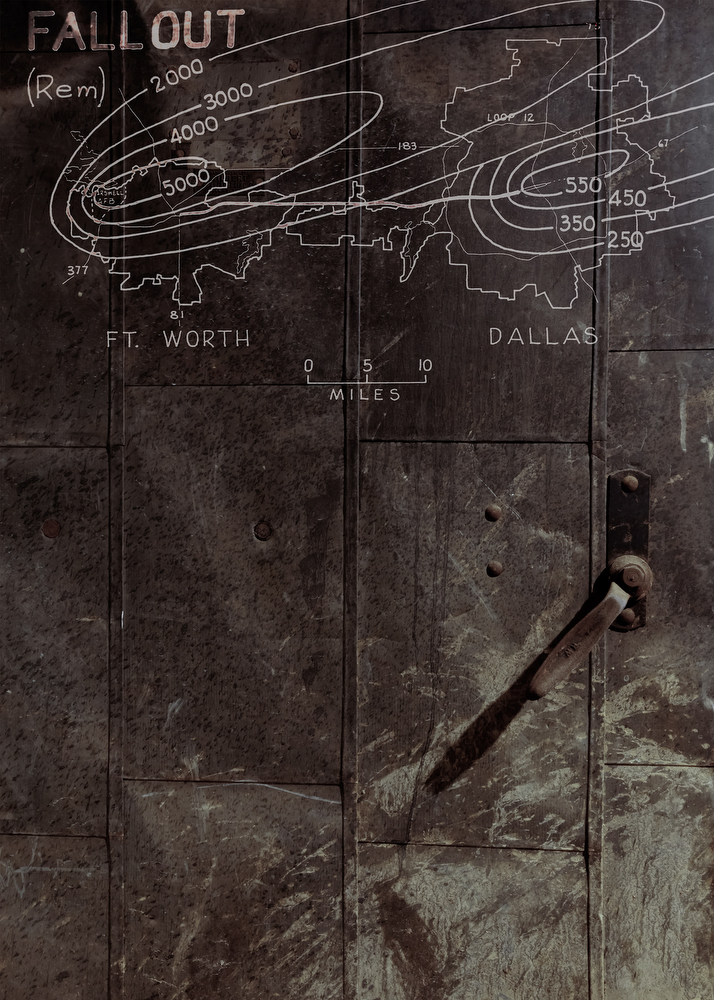

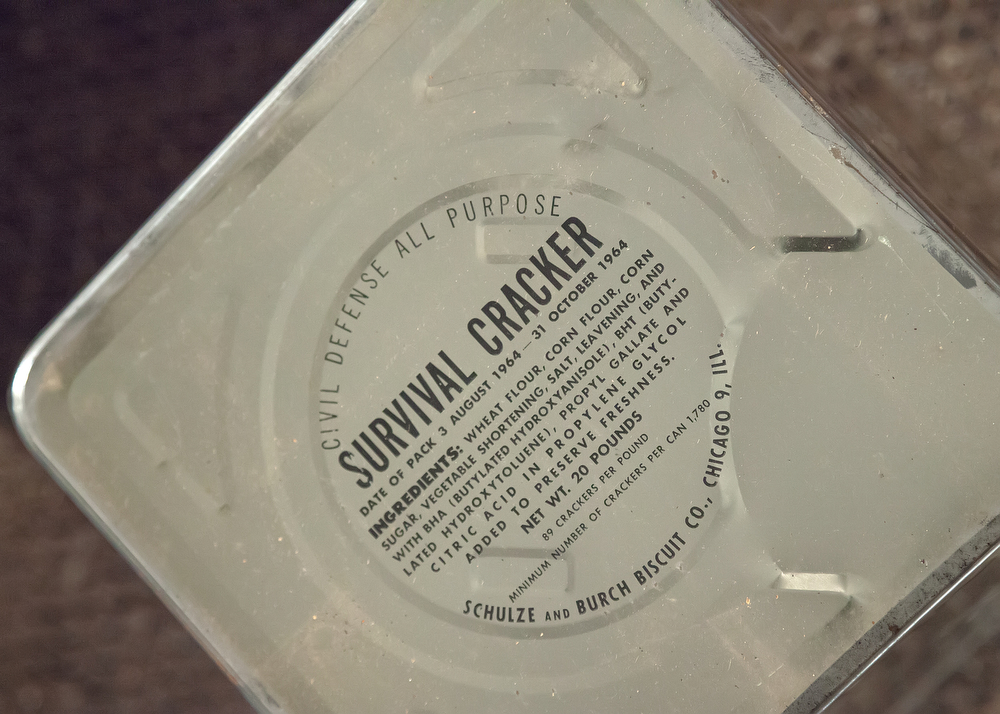

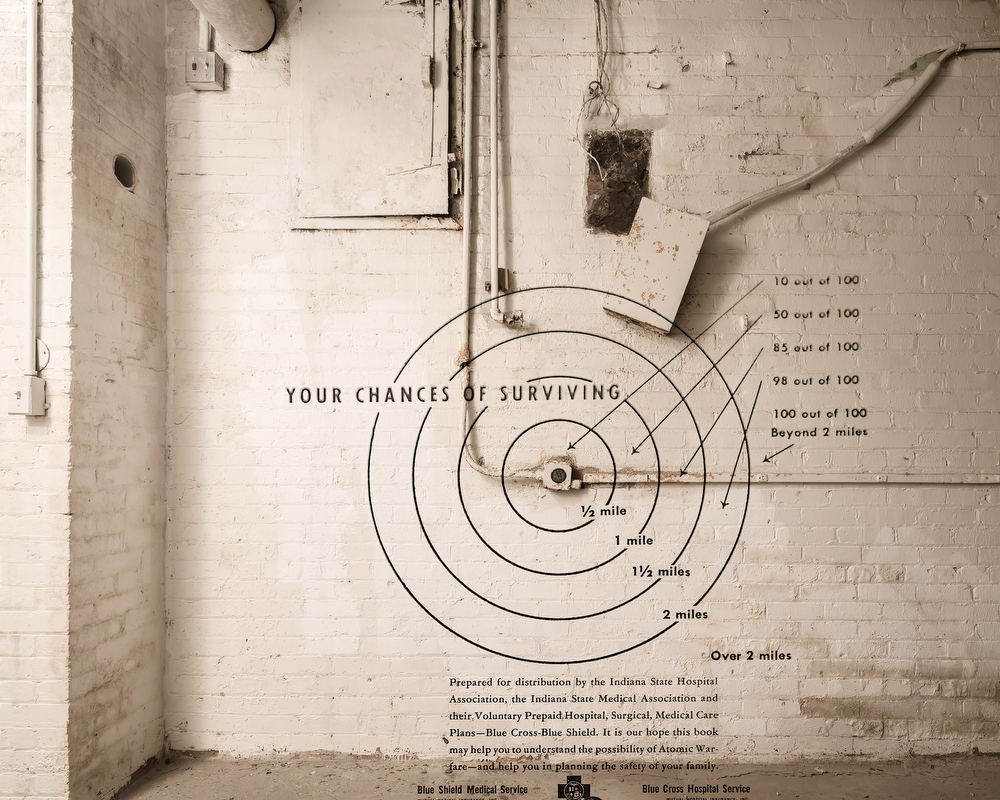

Michna-Bales takes us on a visual tour of decrepit fallout shelters, some public and others private, with shelves still stocked with unopened cans of foodstuffs and “survival crackers” from the 1960’s. In striking similarity to the theme of Neville Shute’s 1957 apocalyptic novel, On the Beach, she also fans the flames of destruction with documents and posters from the era depicting one’s chances of surviving a nuclear blast based upon your distance from it. The images clearly depict the ironies and fallacies of an era that now would appear quaint if it were not for how close Cold War political brinkmanship brought us to near mutual destruction.

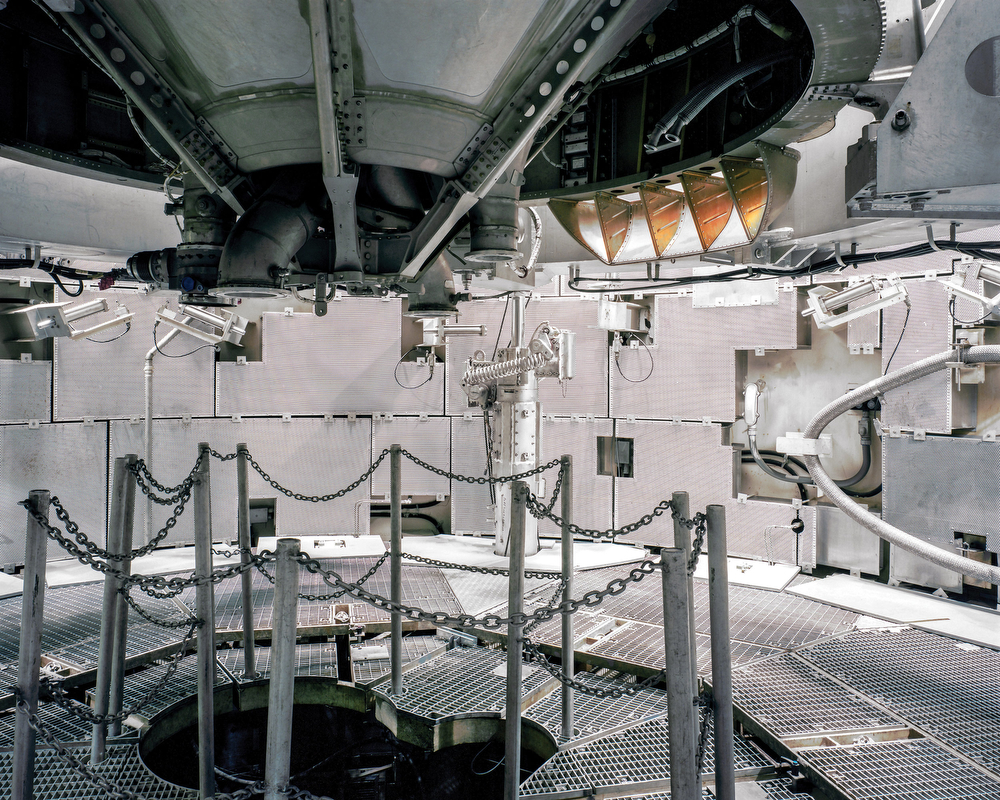

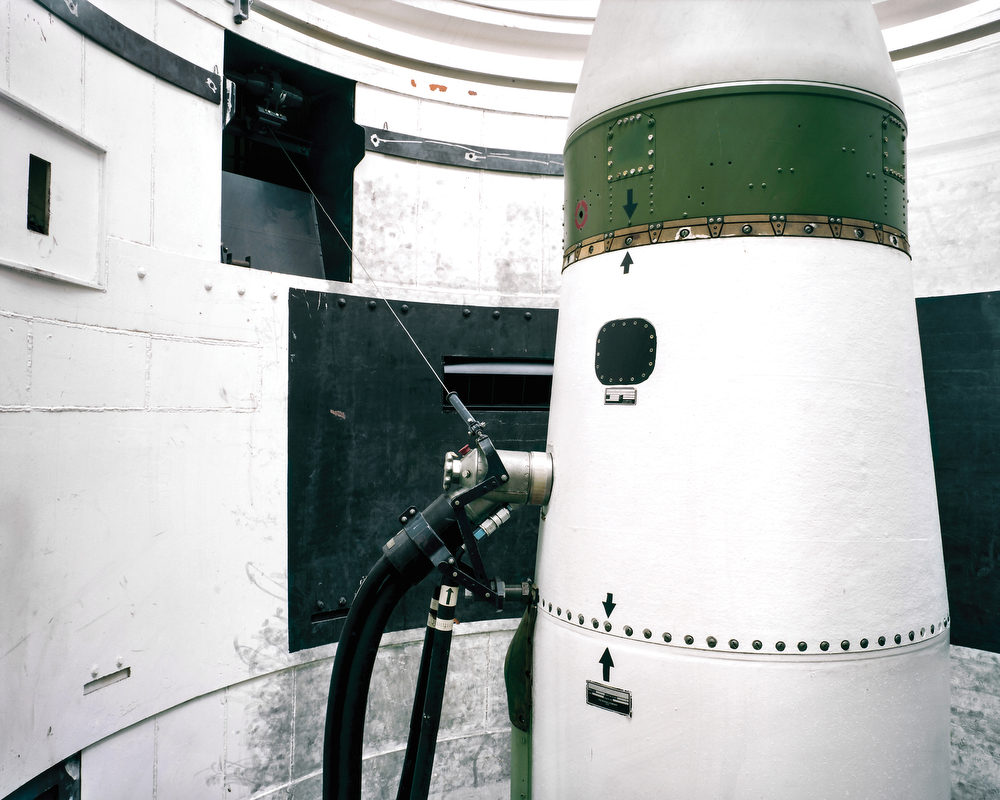

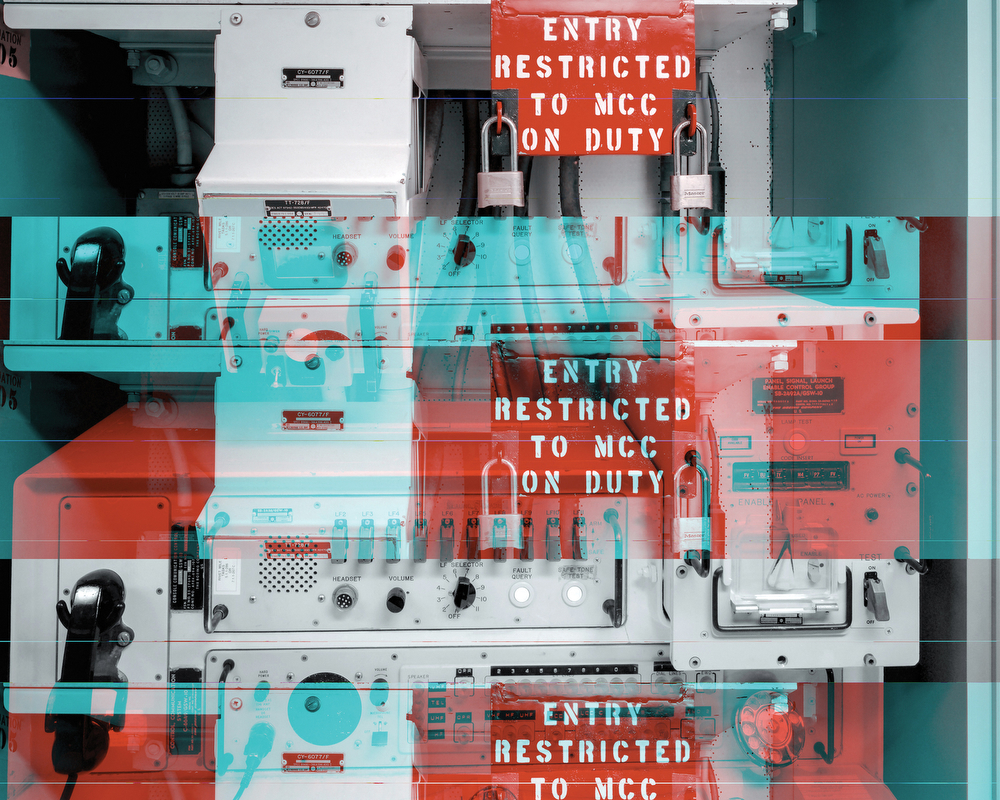

Adam Reynolds covers the destructive side of the Cold War in cold images of cold weapons that required teams of two “missileers” to oversee their readiness to launch a nuclear missile and hence, the project title of “No Lone Zone” since two crew members deterred potential sabotage. The image of two hanging rocket fuel handlers’ coverall suits provides a symbolic glimpse of the destructive power of the missiles they serviced. I was also intrigued by the concept of nuclear tourism that is alluded to in this segment of the book since most of these missile sites were de-commissioned after the fall of the Soviet Union and these two sites are now open to the public. Reynolds also uses glitch art techniques in various images in the book to provide an other-worldly affect to depict the surreal nature of the surreal world view created by the Cold War.

I would be remiss if I did not mention the fine design features of the book that give each project its own space and a clever textured double cover that one can flip to view the opposing project. There are also moments of collaboration between the two artists that utilize glitch techniques and mutual inputs effectively.

The book is published by Yoffy Press and be ordered at: Yoffypress.com

Jeanine Michna-Bales is a fine artist documenting our fundamentally important relationships — to the land, to other people and to oneself — and how they impact contemporary society. Her practice is based on in-depth research — taking into account different viewpoints, causes and effects, and political climates — and she often incorporates found primary source materials into her projects through quotes, ephemera and extended captions. Michna-Bales has released two monographs, “Through Darkness to Light: Photographs Along the Underground Railroad” (Princeton Architectural Press, 2017) and “Standing Together: Inez Milholland’s Final Campaign for Women’s Suffrage” (MW Editions, 2021). She was named a 2018 AIRIE Fellow (Artist in Residence in the Everglades). Her work has been exhibited throughout the United States, is held in many permanent collections including the Library of Congress, and has been featured in numerous media outlets such as BBC World News and the New York Times.

Follow Jeanine Michna-Bales @jmbalesphotography

Adam Reynolds is a documentary photographer whose work focuses on aspects of contemporary and historic political conflict. He pursues long form documentary projects that balance photographic creativity with a journalist’s fidelity to the subject. Reynolds’s background as a photojournalist continues to inform his present work with heavily researched and observed projects with images meant to inform. He holds a Master of Fine Art degree in photography from Indiana University. He began his career covering the Middle East in 2007 as a freelance photojournalist. Reynolds holds undergraduate degrees in journalism and political science from Indiana University with a focus in photojournalism and Middle Eastern politics. He also holds a master’s degree in Islamic and Middle East Studies from Hebrew University in Jerusalem. His first photobook, “Architecture of an Existential Threat” (Edition Lammerhuber, 2017), explores contemporary Israeli bomb shelters.

Follow Adam Reynolds on Instagram: @aprenol13

©Adam Reynolds, No Lone Zone, from Countdown, The game of Battleship is set up in the day room of the Delta-01 Launch Control Facility at the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site in South Dakota.

© Adam Reynolds, No Lone Zone, from Countdown, Minuteman II training missile at Delta-09 at the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site in South Dakota.

©Adam Reynolds, No Lone Zone, from Countdown, The Deputy Missile Combat Crew Commander’s Console with the red safe secured by to locks that contained the launch keys and codes at the Launch Control Center Delta-01, part of the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site in South Dakota. At the height of the Cold War, the United States deployed thousands of Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBM) in a network of underground complexes across the American landscape. These nuclear weapons made up one part of America’s vast deterrent force as it faced off against its ideological rival, the Soviet Union, until its collapse in 1992. And as the Cold War itself has faded from memory, so too have the lessons and fears these weapons once elicited in the general public. Yet the issue of unchecked nuclear proliferation has returned that fear to the forefront. With much of America’s Cold War era nuclear arsenal deactivated and dismantled today, there are a growing number of former missile sites whose mission is to preserve the history and memory of the period. These frozen time capsules are open to the public, catering to an array of nostalgic “nuclear tourists.” As “Shrines to an Armageddon,” they preserve the dramatic vestiges of a power that can destroy the world. The sites stand sentinel as potent reminders of American military might, but also serve as a cautionary tale for future generations. Two such sites, the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site in South Dakota and the Titan Missile Museum in Arizona, are the only remaining ICBM sites in the United States that not only allow visitors into the underground launch control center, but also to come face to face with a (nonfunctioning) intercontinental ballistic missile as well. The project’s title refers to the Air Force’s mandatory two-person buddy system in place at all ICBM sites. This applied both to the on-duty officers on 24-hour alert in the launch control center and to the work crews tasked with maintaining the missiles. The policy was intended as a safety precaution and as a safeguard against potential sabotage. The images pair America’s most prolific ICBM (the Minuteman II) with its most powerful (the Titan II) and offer a calculated look at the nuts and bolts of Mutually Assured Destruction, the mad logic behind nuclear deterrence.

@ Adam Reynolds, No Lone Zone from Countdown, Elevator to the underground Launch Control Center Delta-01 at the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site in South Dakota.

©Jeanine Michna-Bales, from Countdown, From the series “Fallout: A Look Back at the Height of the Cold War in America, circa 1960” 2013 – 2022

©Jeanine Michna-Bales, from Countdown, From the series “Fallout: A Look Back at the Height of the Cold War in America, circa 1960” 2013 – 2022

©Jeanine Michna-Bales, from Countdown, From the series “Fallout: A Look Back at the Height of the Cold War in America, circa 1960” 2013 – 2022

©Jeanine Michna-Bales, from Countdown, From the series “Fallout: A Look Back at the Height of the Cold War in America, circa 1960” 2013 – 2022

©Jeanine Michna-Bales, from Countdown, From the series “Fallout: A Look Back at the Height of the Cold War in America, circa 1960” 2013 – 2022

©Jeanine Michna-Bales, from Countdown, From the series “Fallout: A Look Back at the Height of the Cold War in America, circa 1960” 2013 – 2022

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Michael O. Snyder: Alleghania, A Central Appalachian Folklore AnthologyJanuary 18th, 2026

-

David Katzenstein: BrownieJanuary 11th, 2026

-

Amani Willet: Invisible SunJanuary 10th, 2026

-

Jamel Shabazz: Prospect Park: Photographs of a Brooklyn Oasis, 1980 to 2025December 26th, 2025

-

Andrew Lichtenstein: This Short Life: Photojournalism as Resistance and ConcernDecember 21st, 2025