Luther Price: New Utopia and Light Fracture Presented by VSW Press

We live in a world full of color, texture, and light. In Luther Price’s book “New Utopia and Light Fracture” published by Visual Studies Workshop Press, we are taken into a world that is so like our own and yet purely abstracted. Through this work, Price has enhanced the idea of what film and photography are while pushing the boundaries of our perception.

When looking through this book, I was astounded by the work included. Never before had I seen such intensity within images that can only be described as Price’s thoughts and memories abstracted within each other. With each image, I found myself diving into my own consciousness and discovering new feelings that arose from Price’s work.

Speaking with Tara Merenda Nelson, VSW Curator and Managing Editor for the VSW Press, granted a deeper understanding of Price and the impact of his work. Nelson recently wrapped up the book tour for this publication and shared her insights into the process of creating “New Utopia and Light Fracture,” which Price himself is unable to see in its completion. Thanks to VSW Press, viewers can experience Luther Price’s beautiful and haunting work in full through this new publication.

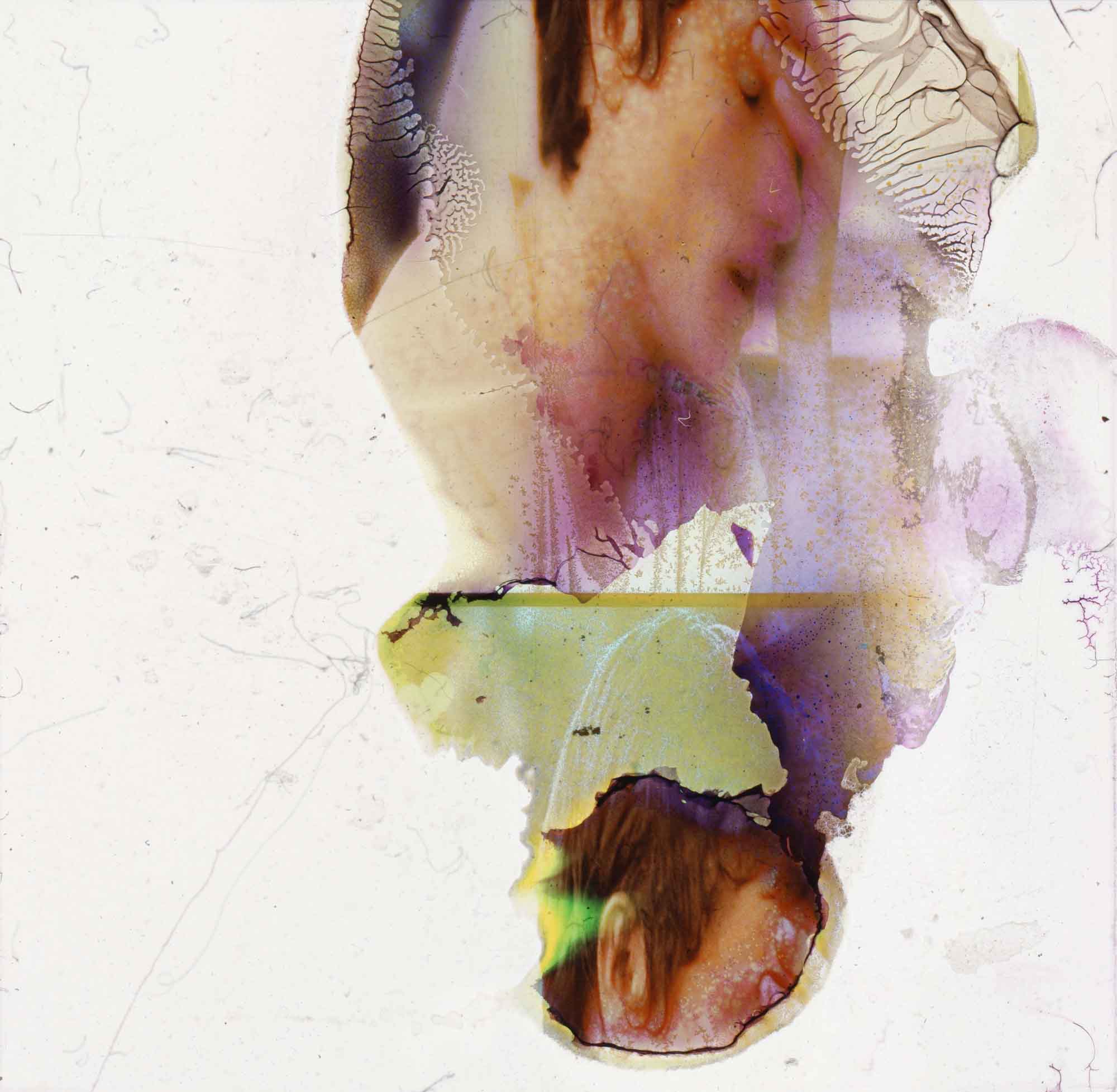

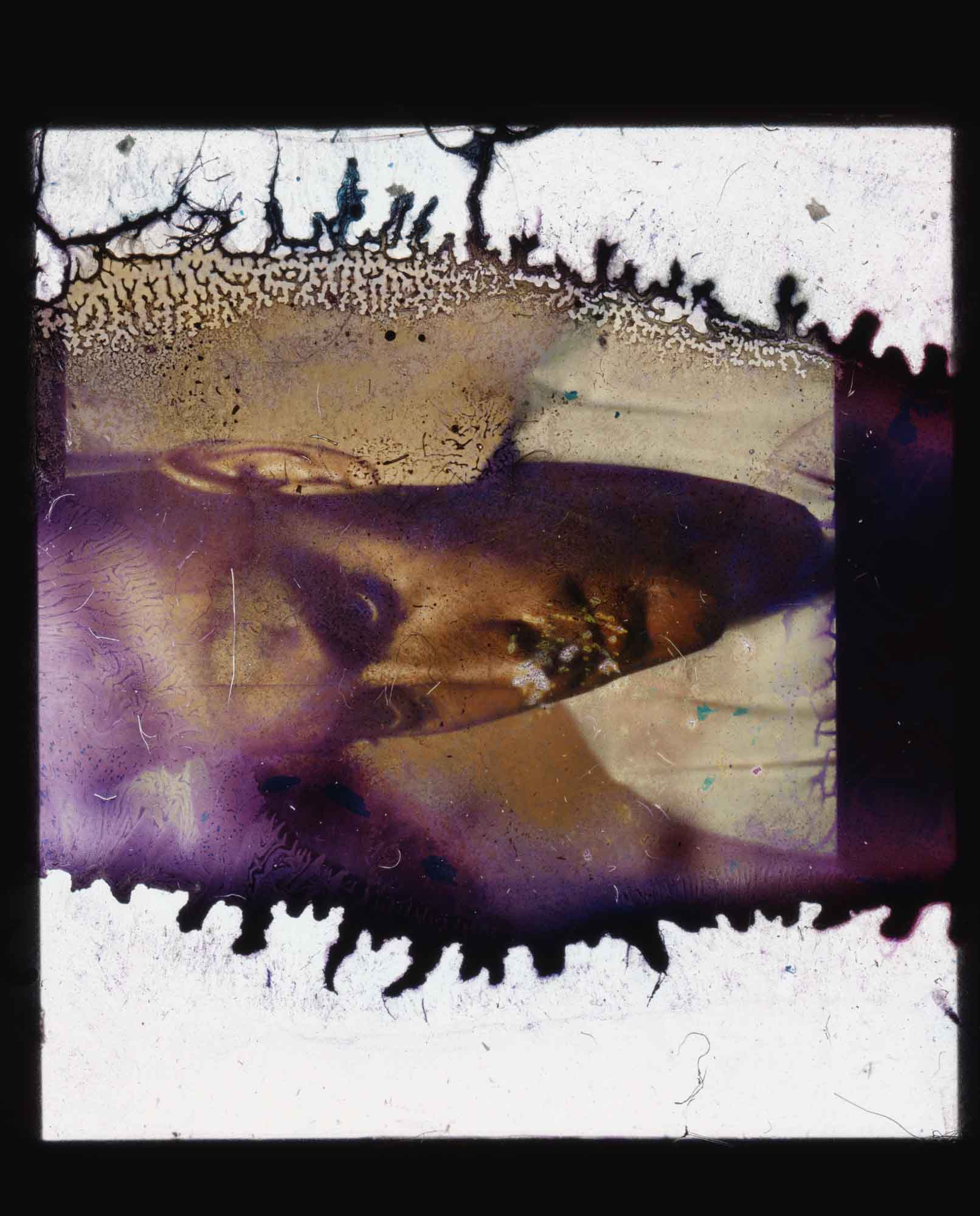

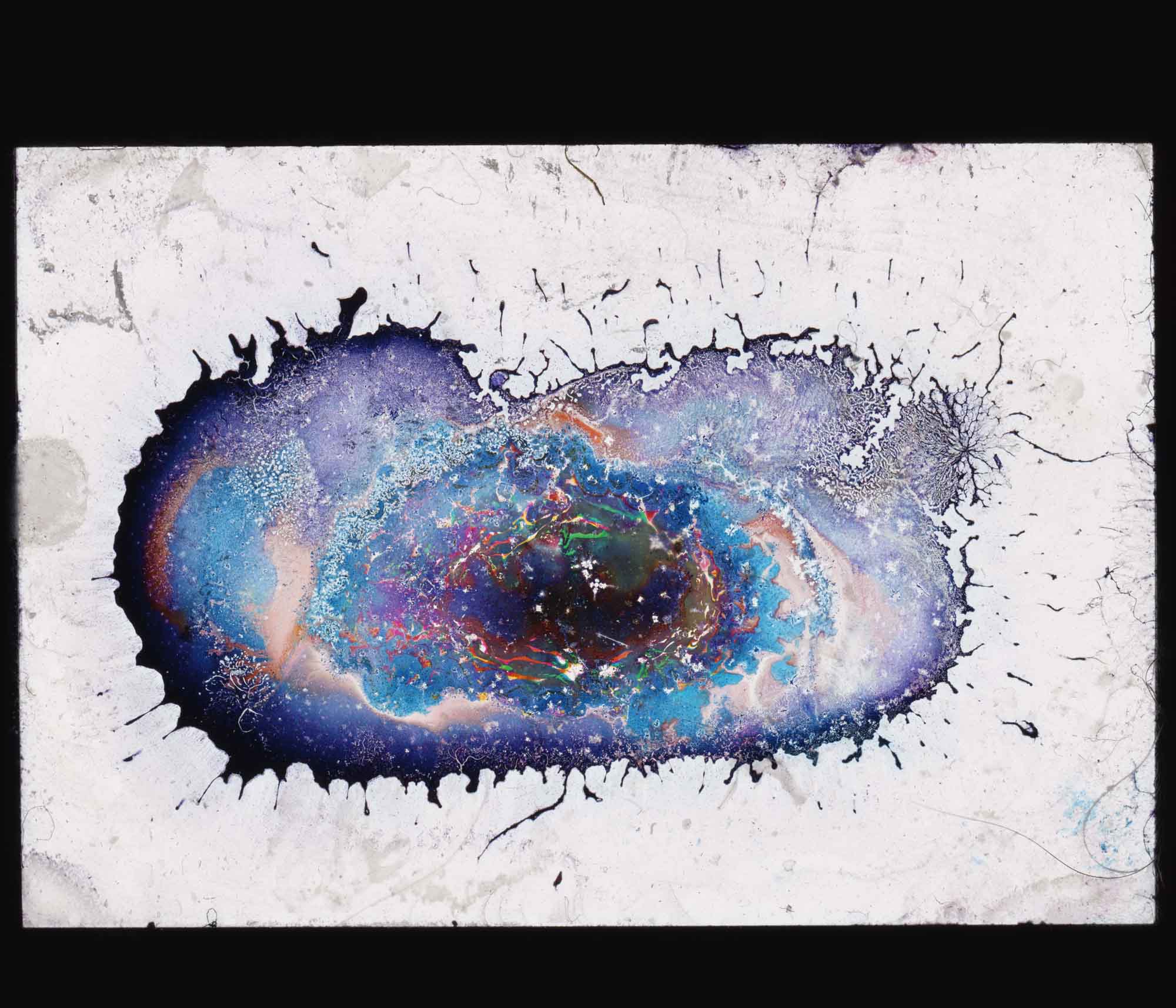

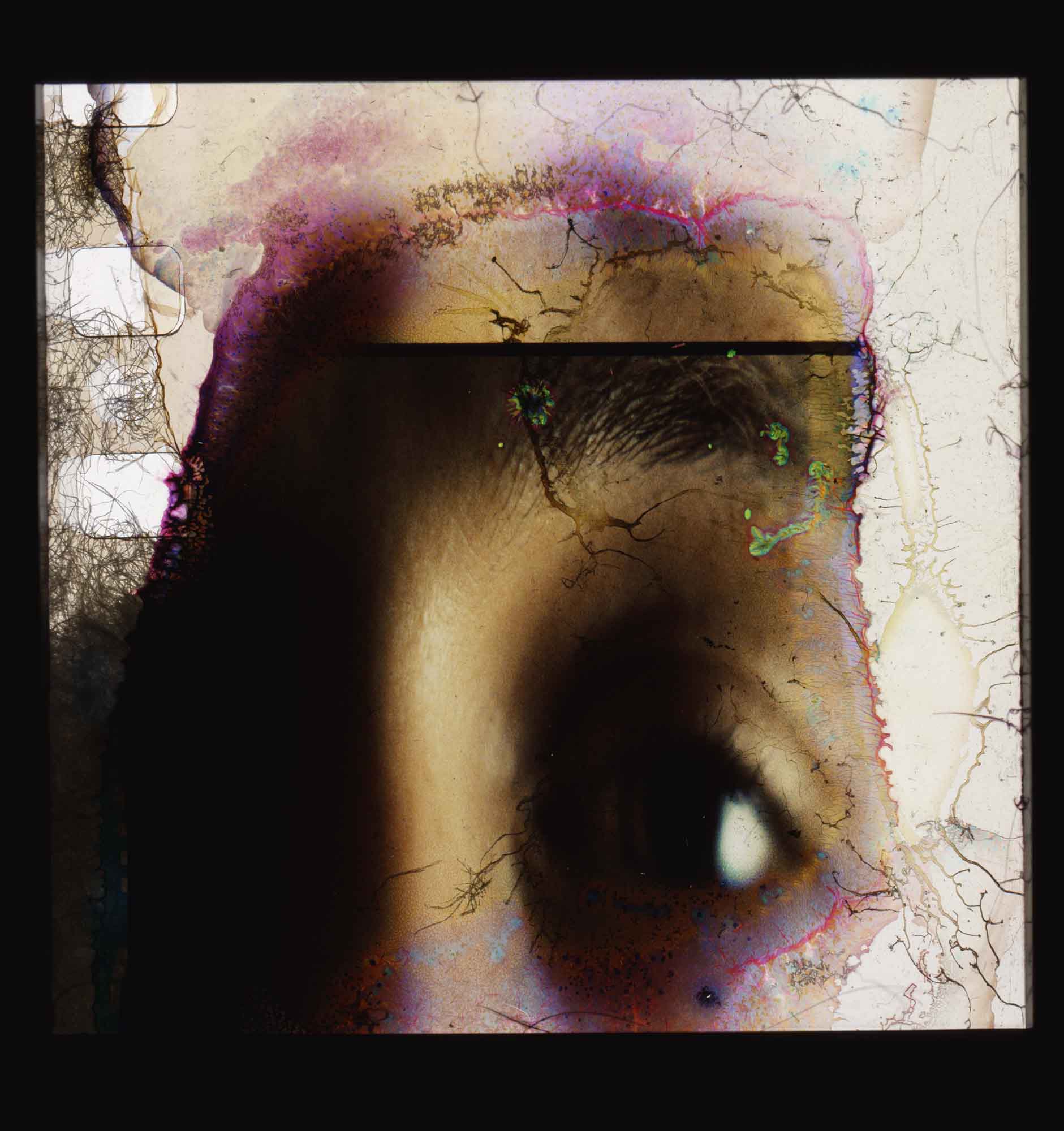

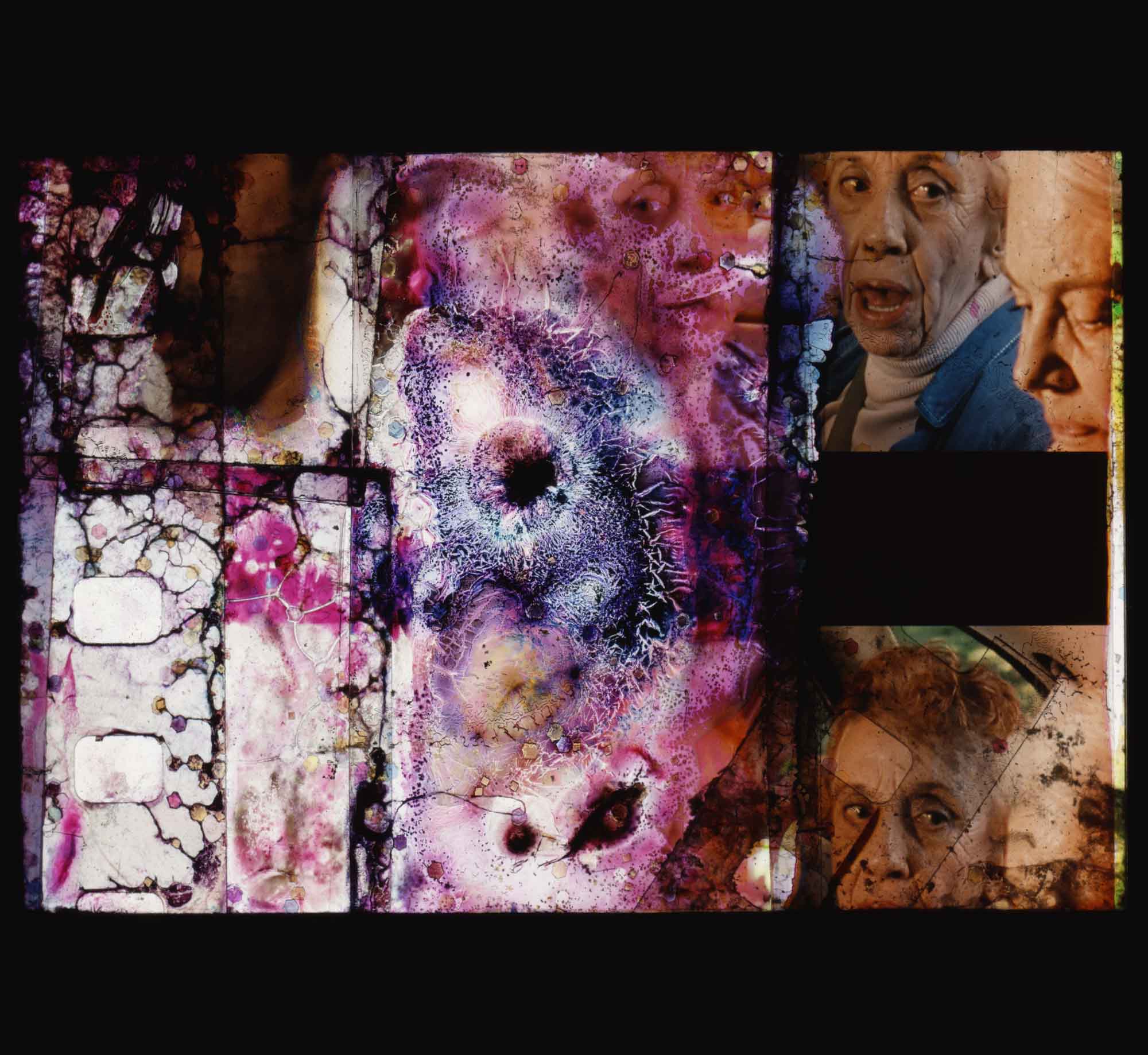

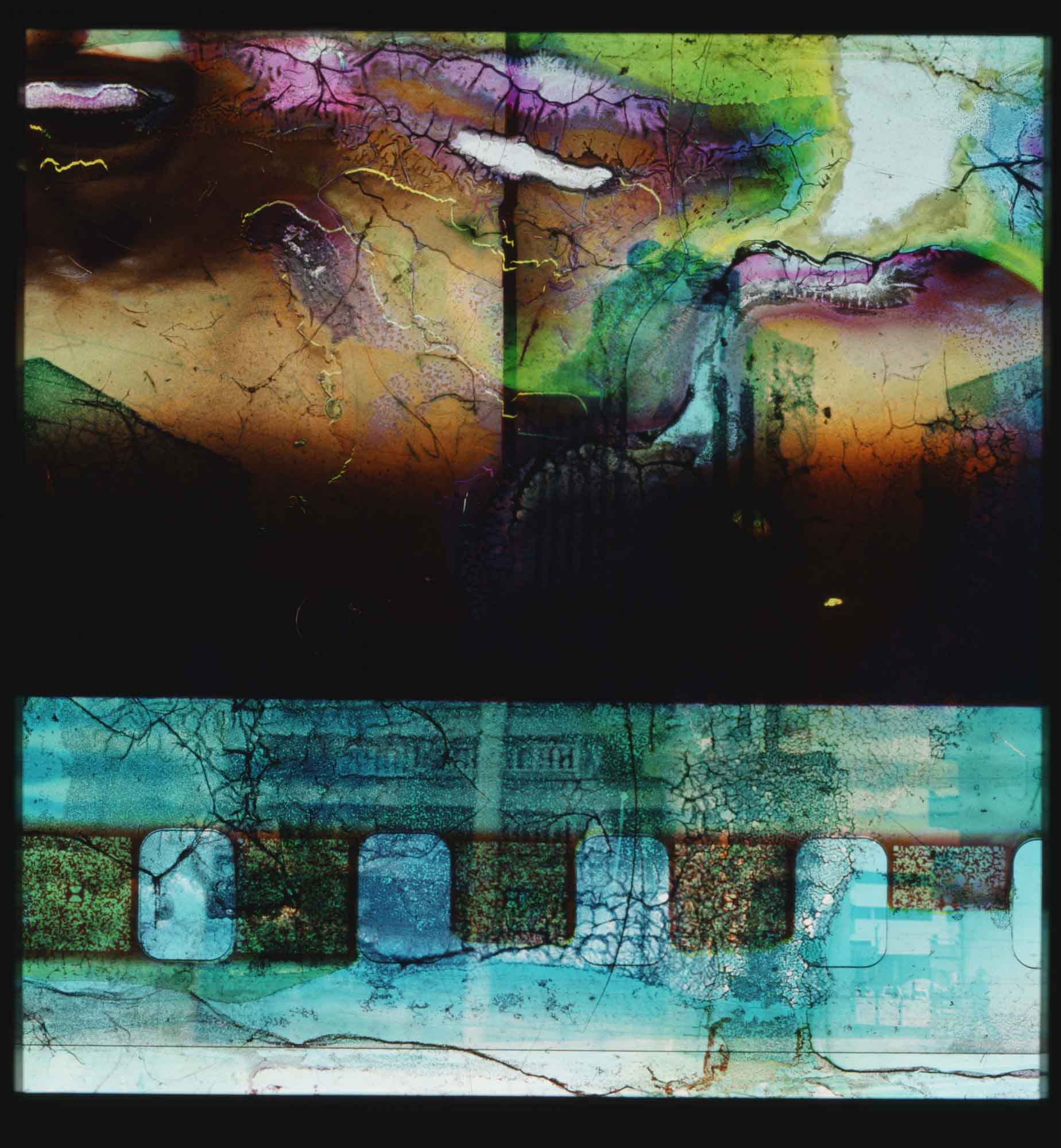

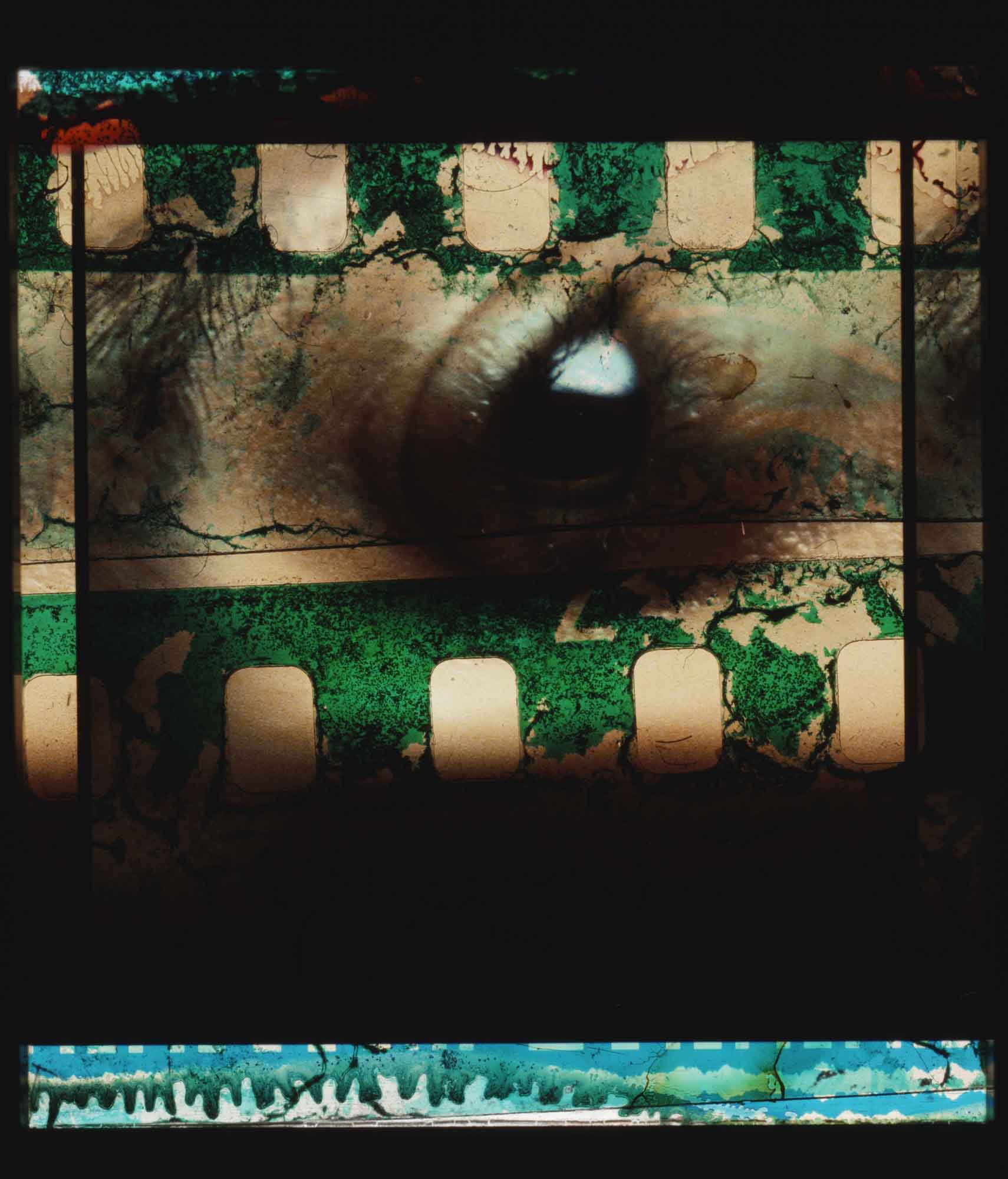

Luther Price (January 26, 1962 – June 13, 2020) was a prodigious artist whose work unearthed the deepest, darkest corners of the human experience. Working in film, sculpture, and performance, his haunting portrayals are often manifestations of personas drawn from lived traumas, thickly layered with paint, glitter, glue, and bodily fluids. Price’s films are sculptural compositions in which images of eviscerated bodies, raw meat, hardcore gay porn, and laughing clowns occupy the same psychic space as quiet scenes of street corners, blue skies and empty clotheslines. Born in Marlborough, Massachusetts, Price attended the Massachusetts College of Art in the early 1980’s, where he studied sculpture and performance before turning to Super 8 film after being shot in Nicaragua in 1985. With the support of Super 8 filmmaker SAUL LEVINE, his teacher at MassArt, Price pushed the boundaries of the “home movie” medium, stepping into each role of the fractured family to conjure complicated apparitions on the scratched surface of the film. His practice evolved to include found footage and “handmade film” techniques, incorporating ink, dirt, spit, splices and the process of decay into the production. Price’s work with 16mm found footage is some of the most sophisticated in the tradition, with more than 80 original titles created in the course of his career. In the last decade of his life, Price created breathtaking collages on 35mm slides, combining the techniques he had mastered in his film works to culminate in single frame compositions. A selection of these slides can be seen in New Utopia and Light Fracture by Luther Price.

“New Utopia and Light Fracture” by Luther Price includes images derived from the depths of Price’s 35mm collages, representing some of the most accomplished work of the artist’s career. The sparse text in the book comes solely from Price’s messages to Shaw over a two year period.

To purchase this book, please click here.

Kassandra Eller: I would love to begin by discussing how the idea of this book came to be. What role did VSW play in getting this project off the ground?

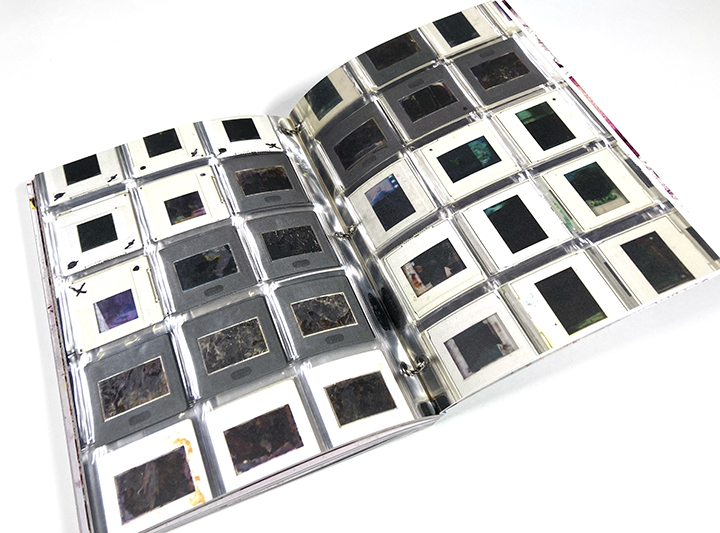

Tara Merenda Nelson: In June of 2017 I invited Luther Price to conduct a 5 day workshop on Handmade Film as part of Visual Studies Workshop’s VSW’s Summer Institute. He brought with him a binder with 164 35mm slides, which he gifted to the VSW archives. After looking at them, I said “We have to make a book with these,” and Luther was excited by the idea. A few days later he met with VSW Press Editor Tate Shaw, who proposed some ideas on how the book could be laid out.

KE: How much of “New Utopia and Light Fracture” was completed when Price was still present? How did you approach decisions regarding composition and sequencing after his passing?

TMN: We created a couple of options for the book that did not include any text, just to consider how these works could exist in book form. It became clear immediately that representing this work on paper would be a challenge, as the slides are both sculptural (as objects) and require some form of illumination to be understood as projections. We considered some options that might reference the formal aspects of the slides, but nothing could come close to capturing their impact as projected artworks. Luther never saw any of the mock-ups, because we were not satisfied that we had an option worth showing him.

It was during this period that the text messages and emails from Luther to Tate (which are now the primary text in the book) were written. The project was tabled for various reasons, as we felt the need to step back and think about how this work could exist in book form. Luther was not well during this period, and that made us more reluctant to push forward on the project. After Luther died in 2020, we felt it was very important to complete the book, and to hear Luther’s voice directly. Tate suggested using the text and emails that Luther had written to him, as it was apparent that Luther was telling us exactly what he wanted to say in the book. We had the slides scanned, and chose excerpts from the images that were emotive but not illustrative. Darkness, saturation and fragmentation were guiding principles for the selection of the images. The sequence of the text corresponds to the timeline in which the messages were sent, and the image sequence groups the two series, beginning with New Utopia, then a break at mid-point that includes cell phone photos sent by Luther, followed by images excerpted from Light Fracture. Finally, we chose to create an eBook companion that includes scans of each slide, so they can be seen as illuminations as intended by the artist.

KE: We touched a bit on this in the previous questions, but I would love to discuss how Price’s death has impacted how “New Utopia and Light Fracture” is presented.

TMN: Luther was almost always there when his works were shown, and his energetic presence was deeply embedded in the experience of his work. He cared deeply about his audience, and took great care to deliver a performance that would be memorable to them. For every exhibition he chose his programs very carefully, often resequencing slides or swapping titles once he was in the room with the audience. He wanted to be seen and heard. He wanted to communicate.

I take the responsibility of representing Luther’s work to new audiences very seriously. I am not Luther Price, and I cannot communicate on his behalf. But I was his student and his friend, and I have seen him present his work many times. On this tour, I show the slides as dual projections on 35mm slide projectors, as I saw Luther do with his other slide works. Luther sometimes added black leader to his 16mm films to interrupt/underscore a particularly impactful moment. I have resequenced the slides several times, adding intermittent gaps between them to provide space for the audience to sit with what they have just seen.

We showed the slides on a continuous loop in a beautiful installation at Light Industry back in October. At that show Ed Halter, one of the curators at Light Industry and the author of the introduction to the book, remarked “you know, Luther never would have shown all of these slides at once”. He’s right. But as a curator, I have chosen to exhibit all 164 slides in this collection. I want them to be seen, all of them.

KE: During March, you were on a book tour for Luther’s book in many different

cities. How has this experience affected the way you interact with “New Utopia and Light Fracture?” How has your perception of this book changed since its inception?

TMN: Once we had decided how it would be designed, I reached out to a selection of Luther’s closest friends to share with them the idea behind the book, and to hear their thoughts on the approach. It was important to me that Luther’s community felt included in this project, and that the book didn’t take them by surprise. It became clear in these conversations that we were all still grieving his loss, and that it would be cathartic to have an opportunity to share his work with new audiences. The idea of a book tour with the slides came out of these conversations. I began calling it a “grief tour”.

Now that the tour is nearly over, I would call it more of a celebration. At almost every location, the local curator has chosen a selection of Luther’s super 8 films to show before the slides, giving the audience an opportunity to understand Luther’s expansive creative practice. The films show his range as an artist, and provide a context for the slides, which were his primary form at the time of his death. I have found that these screenings have made new audiences more curious about who Luther Price was, and in the book they have the opportunity to hear his voice directly.

KE: Let’s take a step back and talk about your past with the artist. I see that you were a student of Price’s. What lessons did you learn from Price and his work during your time as his student? What about his work made you want him to join a workshop at VSW later on?

TMN: I chose to go to graduate school at MassArt in part because Luther Price was there. I had seen a couple of his films and I was drawn to their audacity, honesty and innate ability to punch you in the face and in the gut, all at the same time. That’s what I aspired to do in my work. In the classroom, Luther would show us hours of films that inspired him – Kurt Kren, Anne Charlotte Robertson, Kenneth Anger – and he loved to tell stories. He told incredible stories about performances he had done, people he had met, his family. The workshop was 5 hours long, and we would hang out in the screening room for the first 3, then head down to the workshop and go wild making our own films.

I must add – Luther was a meticulous splicer, so if we showed up in the booth to show our own films with inadequate splices we would be kicked out (as I once was). And if we ever dropped a frame or more on the cutting room floor he would insist that we pick them up and put them in a baggie so we could “use them for something else later”. I once threw away film I had shot because I had underexposed it, and Luther made me retrieve it from the bin. He convinced me that there was something there, I just needed to uncover it. He told me “Don’t be afraid of the darkness. Don’t be afraid to make a bad film.” That film became one of my most exhibited works, Snow.

When I began teaching I realized that his work was hard to find and many people hadn’t seen it at all, so I would show it whenever I could. When I had the opportunity to invite him to show his work or teach a class, I did not hesitate, as I knew what an influence he would have on students. He was a superstar in my mind.

KE: Is there anything I didn’t mention that you would like to add?

TMN: There is always more to say, but I think you have asked very good questions. I might add that Luther was one of the hardest working artists I have ever known, with an expansive practice in sculpture, performance, writing and journaling. I hope that his archive will someday be available to the public so that he can continue to inspire – and challenge – artists and audiences in the future.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photography Educator: Erin Ryan StellingJanuary 9th, 2026

-

The Female Gaze: Alysia Macaulay – Forms Uniquely Her OwnDecember 17th, 2025

-

Bill Armstrong: All A Blur: Photographs from the Infinity SeriesNovember 17th, 2025

-

Robert Rauschenberg at Gemini G.E.LOctober 18th, 2025

-

Erin Shirreff: Permanent DraftsAugust 24th, 2025