Dakota Mace: Listening to the Land

A pair of silver gelatin cameraless photographs, marked by painterly drips and splatters of photo chemistry and punctured by delicate patterns of red glass beads, were the first works by Dakota Mace that I encountered in person. This diptych, Náhookǫs Bikǫʼ I, registered as much more than an aesthetic exercise; these chemigrams presented a field of information about Diné culture, cosmology, and the design motifs that carry stories through ancestral lines of cultural practices. My research in experimental approaches to photo-sensitive materials had led me to visit and write about Direct Contact: Cameraless Photography Now, a diverse exhibition of works that pushed the boundaries of photography to mesmerizing effect. Since then, I have followed Dakota Mace’s work and career with fervent interest. She is a Diné (Navajo) artist whose interdisciplinary practice exemplifies the traits of Indigenous aesthetics: sovereignty, kinship, ceremonial customs, storytelling, and deep connections to homelands and place. Materiality and ancestral memory emerge as the most salient elements, and the following overview of her recent solo exhibition, with insights gleaned from a lengthy conversation at her studio, demonstrate the ways that Mace has found balance between vigorous experimentation and Diné tradition.

Instagram: @dmaceart/

Earlier this year, on one of the coldest days in January, I drove up to Madison, Wisconsin to visit Mace in her studio located in the Arts + Literature Laboratory. With many exhibitions on the horizon for 2025, her studio was full of works in progress and various stages of packing and organizing. Anthotype prints dyed with Osage orange and eco-printed silk panels ready to be steamed sat to one side; these new works would soon be installed in a group exhibition A Tale of Today: Materialities that opened in early February at the Driehaus Museum in Chicago. Neatly wrapped framed works were stacked in the back of the room, perhaps in preparation for shipment to other group exhibitions later in the year: Smoke in Our Hair: Native Memory and Unsettled Time at the Hudson River Museum, and An Indigenous Present at the Institute of Contemporary Art Boston. The rest of the studio was consumed by final preparations for her first major solo exhibition, DAHODIYINII – SACRED PLACES, which opened at SITE Santa Fe at the end of February. I caught glimpses of some of the works for the exhibition: a large weaving of natural churro wool with a deep red band dotted with glass beadwork, carefully folded on a table; a tanned sheepskin stretched on an easel; and several clamshell boxes filled with hundreds of cochineal-dyed cyanotypes. On a table near the windows, a tanned deerskin was laid flat with a large, beaded panel atop it, awaiting attachment; here she sat, threading ribbon through dozens of silver jingle cones while we talked. Our conversation spanned from her experience at the Venice Indigenous Arts School that coincided with Jeffrey Gibson’s Venice Biennale exhibition in 2024, to her undergraduate studies in photography at the acclaimed Institute of American Indian Arts, to building relationships with curators, to a Diné concept of cyclical time and memory: Ałk’idáá. Mace is soft-spoken, but unmistakably self-assured; when speaking about her work, she consistently returns to Diné philosophy, the importance of collaboration, and the agency of materials.

These imperatives are evident in her photo-based work, particularly the cameraless methods that she employs in her series of chemigrams and cyanotypes. These practices which make photographs by circumventing the inscriptive tool of the camera open up new possibilities for accessing the language of memory. Mace’s methods underscore photography as a material medium, a temporal medium–a fertile combination for exploring the language and ecology of memory. But it is primarily a way of knowing. In Mace’s hands, photography becomes a method of Diné epistemology: a way of knowing and a transmission of knowledge.

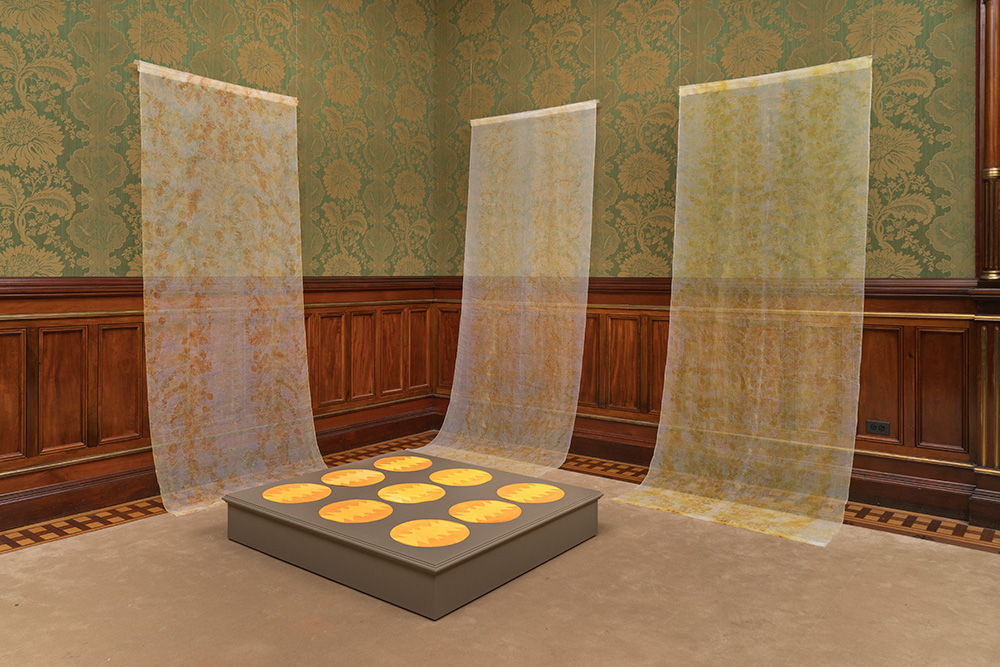

Dáda’ak’ehgo Litso (there are yellow fields all around), 2024. Panels of eco-printed silk with a golden floral pattern hang in one of the bedrooms in the Nickerson Mansion for A Tale of Today: Materialities. Installation photo by Bob (Robert Salazar and Robert Heishman), courtesy of Driehaus Museum.

Dáda’ak’ehgo Litso (there are yellow fields all around), 2024. Detail of eco-printed silk panel, installed in A Tale of Today: Materialities. Installation photo by Bob (Robert Salazar and Robert Heishman), courtesy of Driehaus Museum.

Like many contemporary Native artists working with photography, Mace must contend with the pervasive visual representations of Indigenous peoples that coincided with the dispossession and violence of the nineteenth century. Rather than using the colonial photographic archive as a point of departure, Mace subverts common methods of intervention, pursuing alternative routes to create a visual language that positions the land as an active witness. While DAHODIYINII – SACRED PLACES presented stories of healing and resilience, it also reckoned with the horrific history of the Long Walk and the internment of Diné people at the Bosque Redondo, known to the Diné as Hwéeldi. Beginning in 1863, the U.S. Army removed the Diné people from their ancestral homeland, forcibly marching thousands of people approximately 400 miles to the Bosque Redondo where they endured five years of internment. Notably, the first known photographs of Diné people were made at forts along the Long Walk or at Bosque Redondo; extant albumen prints and cabinet cards are held in the archives of the New Mexico History Museum.

Eschewing the camera, often seen as a tool of subjugation and surveillance, is one method for approaching this painful history, allowing the land and materials to become storytellers. In her refusal to reproduce any historical photographs or to reinscribe trauma, Mace further affirms her intention: “…it was never about this historical representation of it. That’s why Ałk’idáá is so important to this body of work, because it’s not a linear look into this history.”

Mace’s exhibition at SITE Santa Fe—her first solo exhibition in New Mexico—became the ideal setting to animate the connection between land, people, and memory, through the various forms of her visual language: photography, printmaking, beadwork, weaving, collaboration, and an embrace of ephemerality. Framing the entire exhibition were two site-specific, earthen wall installations, made in collaboration with Keyah Henry, one of Mace’s mentees from IAIA. Infused with cochineal, indigo, and ash from prayer ceremonies, these walls oscillated in their effect, acting as portals to the themes of the exhibition and the embodiment of reverential meditations.

Central to DAHODIYINII – SACRED PLACES was a project by the same name, in which Mace interviewed elders and family members, asking them to share stories about places or memories that hold significance for them. In addition to portraits, these works include photographs, both new and old, responding to the stories she heard: a large juniper tree, a well-worn spoon, a treasured snapshot of a relative. These are paired with cochineal-dyed cyanotypes, grounding the stories and memories to land—yet the installation at SITE gave them new meaning. Suspended from the ceiling in an elevated circular shape suggestive of a hogan, these photographs encouraged viewers to gaze up, as though they were looking up at the night sky. This was one of several clever moves by curator Brandee Caoba, crafting pathways through three sections of the exhibition—Land, Memory, Stars—with exquisite sightlines and spectacular lighting design.

The focal point of the exhibition was undoubtedly the installation of over 1,600 cyanotypes, made in situ at sacred places along the route to Bosque Redondo, a culmination of years of the Dahodiyinii project. Sprawling across the wall in undulating tones of red, magenta, rust, and blue, this massive grid of five-by-seven-inch cyanotypes was a transfixing experience. At a distance, the gradient of the grid conjured geological strata, a new form of topography for mapping memories trapped in the archive of the land. But then, the immense quantity became overwhelming: hundreds of individual prints, made to acknowledge the hundreds of Diné who did not survive the Long Walk and the internment at Bosque Redondo. Moving closer to the installation, slowly examining individual prints, the soft shapes and ghostly forms emanated from the surface of the paper. The land, transmuted through chemistry, was humming.

Mace uses the five-by-seven-inch format to reference the size of a cabinet card, a subtle connection to the unsettling portraits made at Bosque Redondo. She dyes the cyanotypes in cochineal to produce vibrant shades of carmine: a color that references her maternal clan; a color that symbolizes healing to Diné; a color that represents centuries of intercultural exchange amongst Indigenous peoples; a color that is earth itself. In our conversation, Mace credited Zapotec artist Porfirio Gutiérrez as a teacher and guide in the practice of natural dyeing, and in particular learning about the history and cultivation of the cochineal insect—the source of carmine—which became an inspiration for the Dahodiyinii series, incorporating the history of material exchange across the continent into the palette of the photographs.

Detail view of Dahodiyinii. Over 1,600 cyanotypes were installed across the wall. Photo by Brad Trone.

In positioning land as an archive, Mace’s work in Dahodiyinii joins a lineage of artists, writers, and historians that approach land as an active site of social and cultural history—deliberately resisting any reconciled stasis to propose counternarratives to dominant, colonial archives. Moreover, Mace’s cyanotypes made in situ at sacred places present the land as a counter-memory, a concept developed by archaeologist Alfredo González-Ruibal which emphasizes soil itself as both an ecofact and an artefact, transcending the divide between nature and culture. This approach to soil—or landscapes more broadly—provides a framework for engaging sites of repressed memories and trauma, including a place such as Hwéeldi. In this regard, Mace’s methodologies for collaborating with the land of Hwéeldi find some alignment with the work of Serbian artist Milica Tomić and her concept of investigative memorialization, or the contemplative photographs of American artist Dawoud Bey made along the Richmond Slave Trail. While neither Mace nor Tomić nor Bey are archaeologists, they are all committed to revealing stories that are literally embedded in the land—not as an abstraction but as a crucial and active agent in the process of knowledge formation. And yet, when I listened to Mace explain the concept of Ałk’idáá, I began to see her practice as a form of archaeology, a reading through time—neither backwards or forwards but through time, through the sacred places she visits to commune with ancestors and listen to the land. For Mace, bringing these stories to the surface is an act of healing.

Material culture of the Diné incorporates symbols and emblems drawn from Diné cosmology and creation stories, and the final gallery of the exhibition explored this relationship to the stars through silver gelatin chemigrams, vivid blue cyanotypes, and an earthen wall infused with indigo. Through her own adaptation of constellations, Mace renders variations of sacred designs that convey aspects of the Navajo creation story, like the Spider Woman and the Whirling Log. Coming from a long lineage of silversmiths, Mace’s series of chemigrams, Béésh Łigaii (Silver) and So’ (Stars), carry additional ancestral knowledge. By working with an emulsion imbued with silver, Mace tethers the materiality of each unique print to the traditions of Navajo silversmithing, utilizing the spontaneous application of photographic chemistry to conjure the cosmos.

During our conversation back in her studio, Mace definitively stated, “Land is always the memory keeper.” Guided by this belief and a synthesis of materials, Mace has developed a sophisticated visual language for telling the stories of her ancestors. More importantly, by framing DAHODIYINII – SACRED PLACES within the concept of Ałk’idáá, Mace’s work is an assertion of temporal sovereignty, holding the memories apart from any imposed historical narrative. The land has knowledge to share, and through intentional use of materials, Mace listens to the land and becomes a conduit to bring those stories to a new realm.

Installation view of chemigram series So’ (Stars) II and Béésh Łigaii (Silver) I, SITE Santa Fe, 2025. Photo by Brad Trone.

DAHODIYINII – SACRED PLACES was on view at SITE Santa Fe from February 28 – May 19, 2025. Mace’s work is currently on view in the exhibition Smoke in Our Hair: Native Memory and Unsettled Time at the Hudson River Museum through August 31, 2025. Her work will be on view in the upcoming exhibition An Indigenous Present at ICA Boston, October 9, 2025 – March 8, 2026.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026

-

Carolina Baldomá: An Elemental PracticeJanuary 5th, 2026