Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel Window

Fig. 1: Robert Frank, View from Hotel Window, Butte, Montana 1956 © Robert Frank Foundation, from The Americans

Recently I was able to travel to the western United States while working on a long-term photographic project. While planning my route, after seeing that I would pass through Butte, Montana, I had what I thought was an original idea: re-shoot Robert Frank’s View from a Hotel Window. In 2021 I’d done a re-photography project with a Brooklyn neighborhood as the subject using my own images made forty years prior; applying the same time comparison concept to an image made by such an influential photographer would an interesting challenge.

As it turns out, many people before me have had this very thought and thus I would not, by a long shot, be the first photographer to make pilgrimage to the spot from where Frank made his well-known and evocative image of 1956. It’s quite a testament that this unassuming picture had such an impact on so many practitioners of the craft. While in Butte, Robert Frank was in the process of traveling about the United States gathering material for what would be The Americans; my capture, also made from the ninth floor of the Hotel Finlen, would come sixty-nine years later as I travelled north and south documenting along the continental divide.

~ ~ ~

I began my study of photography as an undergraduate at Indiana University in the fall of 1979. While Robert Frank’s (in)famous book had been published twenty years earlier, it was still an enormously influential body of work. Indeed, I continue to stress its importance in my documentary photo classes today. At the time of its publication, however, it’s safe to say Frank’s book initially rubbed some critics the wrong way, primarily as having a limited view of the United States. Sarah Greenough writes, “Initially excoriated by critics, The Americans was soon passionately embraced by legions of younger photographers, who responded to its ruthless honesty, soulful lament, and unsettling grace.”

It’s intriguing to consider how seminal works might influence the creative production of subsequent photographers. After departing Indiana to finish my degree at Pratt Institute, I climbed onto my Brooklyn rooftop one snowy night to see if an image could be had. I’m not sure I had the Butte picture in my mind at the time of shooting, or later when I first saw it on a contact sheet, but I feel Frank’s beatnik spirit infused the work at some point along the way.

There are similarities to Frank’s Butte image with the old-school chimney pipes and wet tarpaper roof material, but more crucially in the off-hand composition, with no single object as its focus. It does not depict a decisive moment but rather suggests something more sustained, a lingering mood. The Brooklyn image also sports the grain and contrast only high-speed thirty-five millimeter film can organically provide. The horizontal scratch near the top of the frame testifies to the celluloid base of the analog process being used—not unlike how streaks visible on Julia Margaret Cameron’s albumen prints convey her use of collodion wet-plates.

A decade later, I made an image on Monhegan Island when Frank’s image was undoubtedly in my mind—with the results being, embarrassingly, a little too on the nose.

With re-photography as the task at hand, we should discuss the work of Mark Klett, Ellen Manchester, and JoAnn Verberg via their Rephotographic Survey Project made between 1977 and 1979. While works by the likes of Timothy O’Sullivan and William Henry Jackson (created in conjunction with 19th century governmental surveys of the west) were represented in photo history texts, Klett et al would bring those historical views into the contemporaneous consciousness anew with their book of 1984, Second View. With painstaking research and a rigorous field technique, this corpus made an important connection between the collodion era with that of the time when the use of Polaroid Type 55 was a trend.

Fig. 5: Mark Klett and Gordon Bushaw for the Rephotographic Survey Project Castle Rock, Green River, Wyoming 1979

Based on an elegant and straightforward notion, the Rephotographic Survey Project produced a complicated and influential body of work. It juxtaposed western myth-making with concern for the environment; the history of westward expansion with contemporary land use. It then wove all of that into the history and tradition of western image making. Created not long after the New Topographics movement exploded, the RSP continued a new way of looking at landscape photography, removed from that of Ansel Adams and other modernists of his ilk. Ultimately Klett’s project, spanning a hundred years, illustrated an intriguing examination of time very much beyond the hundredths of a second with which photographers most often dealt.

~ ~ ~

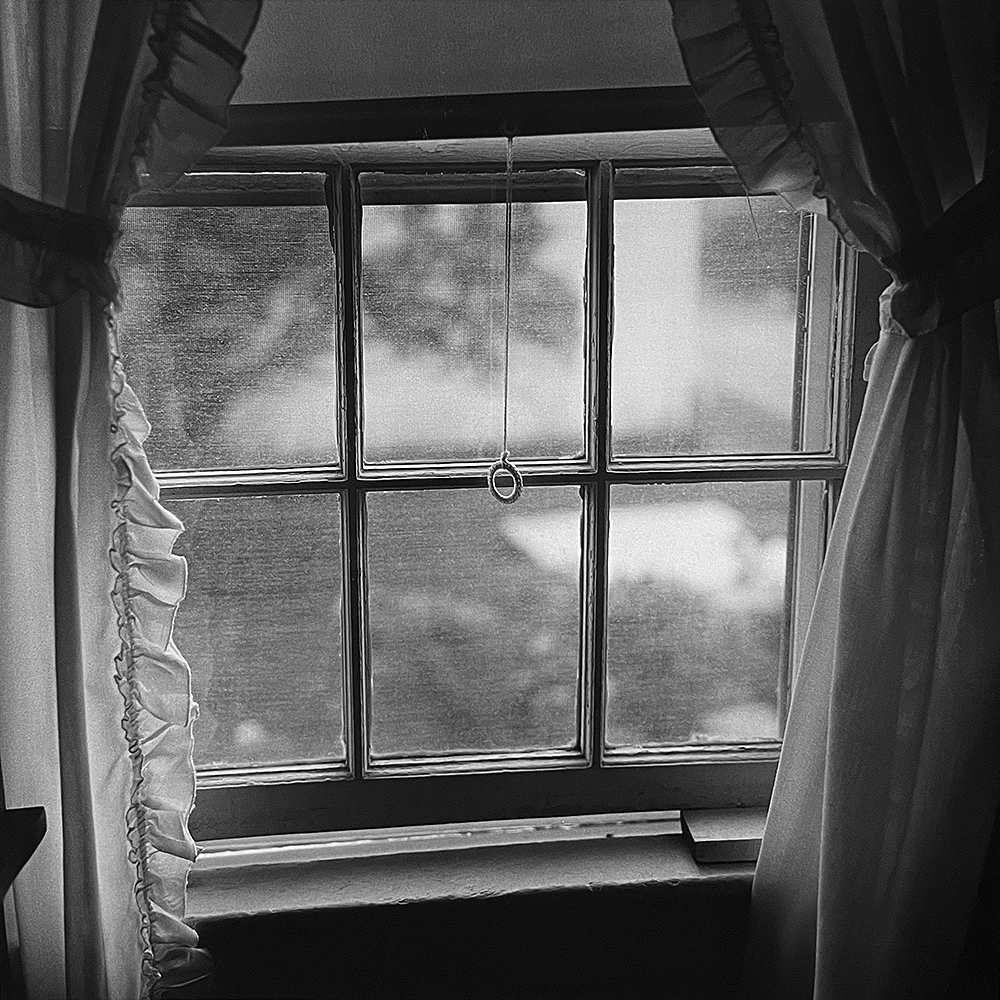

Prior to going west, but after my notion to re-shoot Frank’s image of Butte, I ran across a blog entry by Blake Andrews in which he discussed the well-known picture in relation to a newer one created by Alec Soth (see his book, Broken Manual). I also learned that the proprietors of the Hotel Finlen were well aware of the treasure to which they held title, that being a specific site endowed with photo history while providing a rich view of Butte and the mines beyond. Apparently they created a little mock-up of the room circa 1956, with frilly curtains installed to help with the sense of time-travel. I believe this is the space from which Alec Soth took his photograph seventeen years ago, fifty-two years post Frank.

It’s interesting to note that it was made from a lower floor than the original, given away chiefly by the taller appearance of the chimney pipe but also apparent in the more shallow angle of several roofs seen in the middle distance. Whomever chose this lower floor for the mock-up missed the mark, but this would be corrected by the time I arrived in Butte.

Mr. Andrews, in his blog, notes that Soth focused his camera on the curtains rather than the city and landscape beyond. I’ll note that his switch to a 4:5 aspect ratio provides for more image at the top and bottom of the frame. Wetness plays a part in Frank’s image, by creating high-key reflections on the roads and roof surfaces, but we now see precipitation in the form of snow, providing for a softer feel to what once was a gritty cityscape. In any case, Soth matches the slightly off-kilter composition, seen in his angled address to the window sill.

In the end, once all the bits and pieces of the composition have been combined via the mysterious process of gestalt, Soth has created a poetic homage to Frank’s famous image, engendering a similar melancholic feeling without getting lost in the technicalities of exactly matching spatial relationships (due to him being directed to shoot from a lower floor). The updated image is his, but for those of us who have that of Robert Frank burned into our cerebral cortex, it’s instantly recognizable, like bumping into an old friend.

~ ~ ~

When I arrived in downtown Butte, I was immediately taken by the late-19th century architecture, worn brick walls with ghost advertisements, and a smattering of working neon signage here and there. I wanted to stay in the Hotel Finlen of course, and even though I called well ahead, I had to settle for the attached Finlen Motor Lodge. I made contact with Sandra McNair who works the front desk: the following day she would be happy to take me up to the room where Frank made his photograph. In the meantime I was able to soak up my surroundings: while the hotel itself was built in 1924 and contains a somewhat grand and decorative lobby, the motor lodge is a midcentury time capsule, with exterior turquois panels, interior cinder block walls, and nothing but straight lines everywhere one looks.

At the appointed time the following day, I met Ms. McNair and we ascended to the ninth floor. Since the time of the mock-up room on a lower floor, someone, a visiting photographer perhaps, had determined the correct vantage point for Mr. Frank’s image. As a result, the current suite has been made into a minor shrine of sorts, with Frank’s books, including a copy of The Americans, resting on a side table. She left me to it and I went about trying to lock down the correct position and angle for my camera.

~ ~ ~

When doing a straight, time-comparison diptych, there is tension between similarity and difference. If the photographer can match the original photograph’s point-of-view and camera-to-subject-distance, while using the correct focal length lens, change in the subject itself should come through distinctly. But beyond these straightforward aspects, some creative decisions may be made that can nudge the new picture either toward, or away from, the original, as desired by the photographer.

While working in-camera, one may manipulate the depth of field. Matching the original seems to be in order, though a different range of focus may be needed given a physical limitation or alteration in the historical site. At the Hotel Finlen, for instance, I had to work around a window screen that could not be removed. Beyond focus, one could make changes in lighting at this time as well, though this is another aspect that I would simply mimic, if possible, so as to not cloud physical changes between the two views. In this case I had to shoot when I had access to the space, so time of day, with its idiosyncratic natural light, was not within my control, like the weather itself.

Then there are several characteristics that may be addressed during post-production with the most impactful being the color of the original work. Many time comparison diptychs involve mimicking a piece that was created in a monochromatic (cyanotype, albumen, platinum, toned) or an achromatic (truly neutral) media. In a straightforward sense, matching the original print color would allow the physical changes of the subject to be more readily apparent without the distraction of a shift in hue. On the other hand, using contemporary digital color for the new image can place the new work in the current time as it illustrates advancements in the photographic media itself. Lastly, there are more subtle aspects of optimization that can be utilized, such as tonal manipulation or the addition of digital grain, which might be another way to cozy up to the original work.

~ ~ ~

Once I had the proper location and angle for the camera, I made captures with the blinds completely closed and completely open (more on that below). I also shot several variations in terms of focal length to allow some wiggle room in terms of the crop. Later, while processing the image, while I could have selected a capture that matches the framing of Frank’s image, after much anguish, I chose one where I had pulled back somewhat to include the window frame. This was selfishness on my part as I felt it works to document the fact that I was present in the hotel room in which Frank stayed during the middle of the last century. I decided to retain full color to reflect the time in which it was made, but added grain and used the 2:3 aspect ratio to move it back toward Frank’s version a bit.

East Broadway Street (toward the left side of the frame) and East Park Street (right side), provide a structural grid for this view as well as the original; beyond that, we may assess the changes time has wrought. Four of the original buildings in the center of the composition are extant, with one heavily modified. Several of the surrounding, smaller structures have come down, with there being a noticeable net loss of structures overall. Often with time comparison diptychs, as with my project in Brooklyn, the growth of foliage is significant, but not so here. Perhaps this is related to what lies near the top third of the frame: an area where massive mineral extraction has taken place.

One will note that an entire hillside in the distance has been removed with whatever earth remaining smoothed over; just beyond that is where the renowned Berkeley Pit is located. This mining operation commenced—as an open pit, rather than the previous underground shaft mining—one year prior to Frank staying at the Hotel Finlen. In the intervening years it became one of the largest Superfund sites in the United States. Closed in 1982, an ongoing effort has been undertaken to clean up the site, in particular the toxic water contained in the pit. Noise cannons and drones are utilized to keep migrating birds from pausing there, for their own good. One can visit the site by way of a viewing platform that overlooks the immense pit, which I imagine may be viewed by astronauts flying over in the International Space Station.

~ ~ ~

At the conclusion of my trip west, I stumbled across another notable re-boot of Robert Frank’s famous view, this time made by McNair Evans. I was intrigued with what he composed in that hotel room.

While Evans didn’t match Frank’s angle exactly (note his square address to the window frame), it’s what he does with the blinds and other found objects that impress. [Mr. Evans tells me, while he was at the Hotel Finlen in 2017, the correct room for Frank’s view had recently been vacated by a long-time resident and was undergoing renovation.] Evans has zoomed back to include more of the sill area and room interior. But he goes further, allowing himself creative license to leave the blinds akimbo, if not arrange them so, while also finessing a funny little loop in the drawstring. Likewise, Evans let remain, or placed, various pieces of molding here and there along with a curious, crumpled paper cup. In this way he suggests an unseen human presence, authoring a new, or additional, story for that hotel room. The various accoutrement serve as value-added visual interest, while Frank’s original photograph still comes through loud and clear for those of us who know it.

I would have never taken such daring and creative chances such as these, but I do ardently wish I’d shot the blinds partially open (albeit level), while I was on the ninth floor, most likely never to return. I’m quite straightforward when composing and optimizing images: I lean toward detail and information, often at the expense of expression and drama. In any case, after comparing my photograph with these two fine re-boots, that of Soth and Evans, I now see my effort as informative but rather dry.

~ ~ ~

In the end, there are many ways to handle a re-shoot, with the first being an accurate rendition of the original, spatial relationships replicated to clearly show the changes in the subject and thus valued as a historical document. Mark Klett is the master of the form, but he would not be defined by it. After returning to the historical sites of the original Rephotographic Survey Project two decades removed for his book Third View, he expanded the form by embedding historical views within large color contemporary panoramic views: see Yosemite in Time, made with Byron Wolfe.

While in Butte, Soth and Evans showed us their druthers: create a new and expressive work that might be more about their feelings regarding the subject matter and/or the artist who made the original work. For that school of thought, one must inject soul or poetry into a piece when doing the re-shoot, akin to when a musician covers a well-known and beloved song, or when a director revives an important play. The contemporary artist is tasked with having to both acknowledge the original while crafting it into something new.

Richard Koenig

Genevieve U. Gilmore Professor of Art

Kalamazoo College

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

The Next Generation and the Future of PhotographyDecember 31st, 2025

-

Spotlight on the Photographic Arts Council Los AngelesNovember 23rd, 2025

-

100 Years of the Photobooth: Celebrating Vintage Analog PhotoboothsNovember 12th, 2025