Anna Guseva: The Black Night Calls My Name

Post Co-op

This exhibition brings together four photographic practices that trace the post-Soviet condition as a lived reality shaped by space, fear, discipline, displacement, and the body. Across landscape, portraiture, and long-term documentary work, these artists examine what remains after systems collapse or harden, when “home” becomes unstable and visibility is negotiated rather than guaranteed.

Soviet microdistricts re-emerge as overgrown Arcadias, where vegetation quietly reclaims utopian architecture and transforms control into unpredictability. The psychological aftermath of the 1990s appears as an inherited inner climate, where violence and instability leave lasting marks on identity. In the closed world of women’s football, queer youth find solidarity and refuge within strict boundaries, while the surrounding environment remains hostile. In exile, immigrant communities form fragile “spaces of appearance,” offering temporary belonging while intensifying the tension between survival and assimilation.

Together, these works speak to endurance under unstable conditions: how people adapt, hide, re-root, and continue. Here, “home” is neither guaranteed nor singular. It is overtaken by plants, haunted by memory, protected by rules, searched for in diaspora, and continually reconstructed, one image at a time.

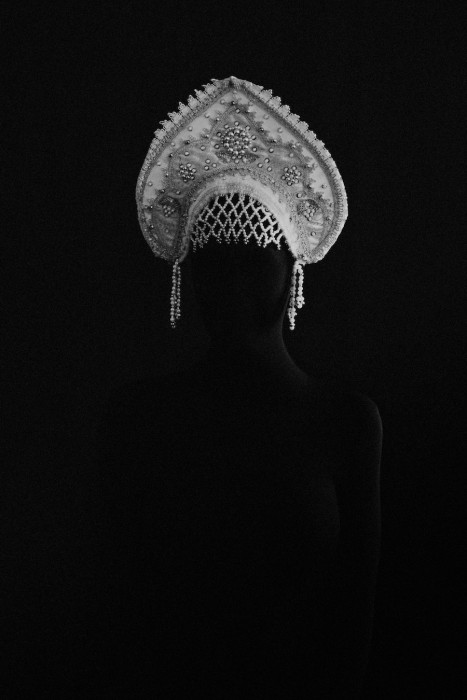

Anna Guseva (b. 1994) is a visual artist born in Russia and based in France since 2018. Her practice engages with the politics of memory, focusing on collective trauma and the weight of difficult historical legacies. Working with performative strategies, she examines how the fragile human body absorbs and reflects structural violence and the invisible pressures of cultural and political environments.

Anna was shortlisted for the Gomma Grant 2024 (announced in early 2025). In 2024, she was also a finalist for the PhMuseum Women Photographers Grant, the Singapore International Photography Festival, the Prix Révélation at Festival OFF Les Rencontres d’Arles, GUP Fresh Eyes, and the Belfast Photo Festival. Her work has been presented in group exhibitions at the National Library of Singapore and the Kommunale Galerie, Berlin, and in portfolio screenings at the PhotoVogue Festival in Milan and Festival OFF Arles. Her series have been published in Fisheye Magazine, Der Greif, Yogurt Magazine, and FK Magazine, among others. In 2024, she gave an artist talk at the photobook festival Nizina.

Follow Anna Guseva on Instagram: @annagsv

© Anna Guseva

The Black Night Calls My Name

I was born in Russia in 1994. It was a turbulent period after the collapse of the USSR, known as the “wild nineties.” Though I was a child, the chaos of that decade left a deep imprint on me.

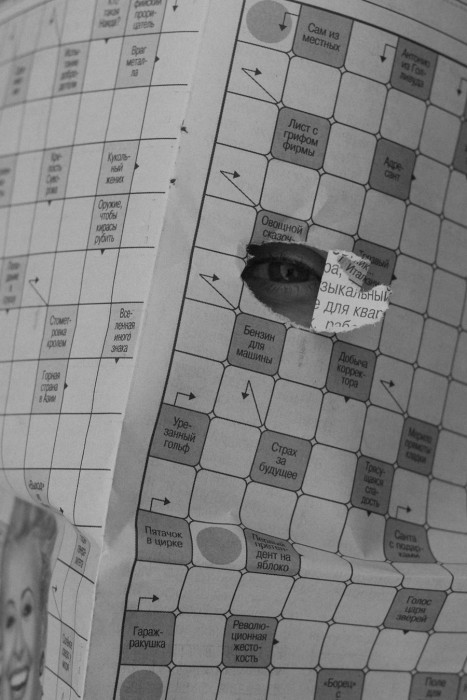

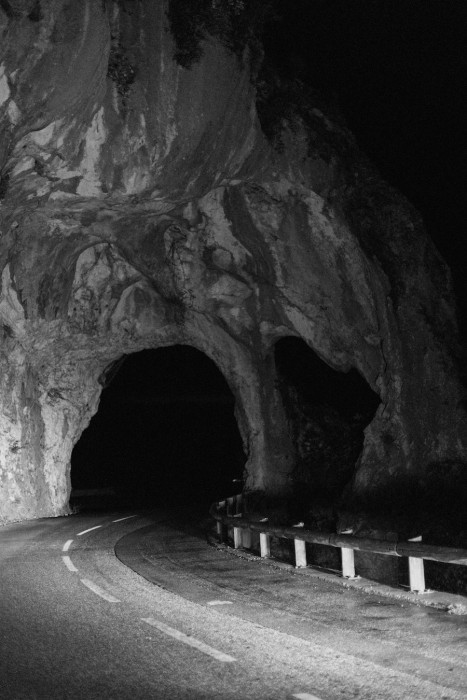

I remember stepping over the bodies of drug addicts sprawled in the stairwell. Syringes crunched underfoot during walks near my house. My grandmother scared me with stories about rapists. On New Year’s Eve, men walked around with broken noses, spitting blood. I remember the unease of watching cars driven by drunks swerve unpredictably. Demonic symbols were painted on the windows of a sectarian apartment. I hid in the corner when the doorbell rang—because that’s how murder and robbery scenes began in TV series. Crime shows ran nonstop. For some, they fueled fear; for others, aggression.

The pessimism, anxiety, and suspicion formed during the 1990s became part of my identity and still manifest in me. But what if, in obsessively fearing aggressors, I unwittingly absorbed their traits? As I study my own blind spots, I fear discovering a monster nurtured in the nineties. The greatest threat is not revisiting frightening memories, but confronting a predator within myself.

As I try to identify areas of uncertainty within me, I encounter a universal mechanism of unpredictability: the external environment shapes us in ways that are impossible to foresee.

Yana Nosenko: How did you begin working on The black night calls my name?

Anna Guseva: The project emerged from my attempt to understand the preconditions that made Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine possible. There are, of course, numerous trajectories for such reflection from analyzing current events to examining earlier chapters of Russian history. However, it was crucial for me to focus on an era that is embedded in my own lived experience and whose consequences I can trace within my own biography. That is why I turned to the 1990s.

© Anna Guseva

Furthermore, what is happening today bears a terrifying resemblance to that decade: the normalization of brute force, the dominance of aggression, and the logic of racketeering over law, rights, and respect for the individual and human life. By engaging with this period, I am not working with the past as a closed historical chapter, but with the ongoing impact of a social environment that continues to shape ways of thinking and responding in the present.

© Anna Guseva

YN: The work is deeply grounded in post-Soviet Russia, yet it touches on fears that feel universal. How do you imagine viewers who didn’t experience the ‘wild nineties’ entering the project?

AG: My aim is not only to document the specific historical experience of the 1990s, but to show a more universal mechanism through which environments influence the individual. Anyone can find themselves in a situation where historical events or the current political reality of their own country begin to shape their thinking, all while remaining only partially conscious.

In a world with a continuous and shared information field, this influence is no longer confined by national borders. We can be affected by the violence, aggression, and instability occurring in other, geographically distant contexts, without immediately understanding how it imprints itself upon us. I imagine that a viewer who did not experience the “wild nineties” does not access the project through the recognition of specific details. Rather, they enter it through an encounter with a sense of uncertainty and anxiety born from the inability to recognize and control the influences of the external world.

© Anna Guseva

YN: Do you see this project as an act of confrontation, healing, or preservation, or something unresolved?

AG: In Russian culture, the 1990s have long been romanticized. Gangsters in films and TV series were often portrayed almost as knights – bearers of a particular code of honor, devotion to their mothers, and loyalty to their gang. The music of that era was frequently reused as a form of cultural exoticism, carrying a deliberately reckless or “wild” aura. Over time, I became increasingly uncomfortable with the realization that I myself had participated in reproducing these narratives – often automatically, without analyzing what they truly carried within them. For me, this project is an attempt to look honestly at the imprint that era has left on me, without romantic and nostalgic filters, even when it leads to uncomfortable discoveries about myself.

YN: Many of the memories you describe are fragmentary and sensory. How do you translate those internal sensations into photographic form?

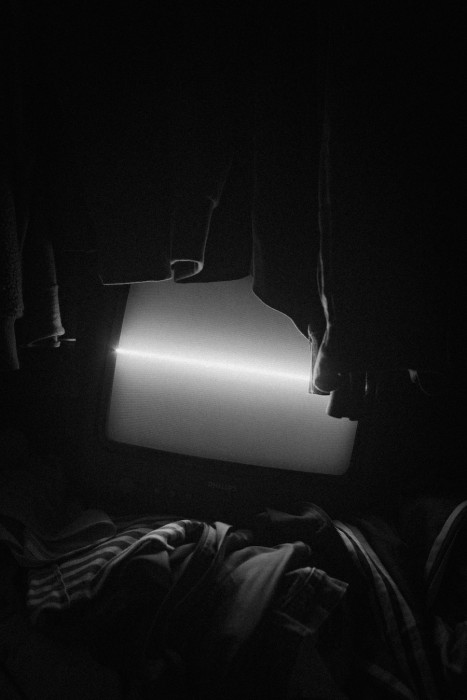

AG: The project took on a performative form and features numerous self-portraits that capture my bodily movements. However, I do not consciously seek a specific corporeal language to express these images; it emerges on its own, rising from within. Most situations connected to that time do not trigger sequential memories in me, but rather bodily flashes.

© Anna Guseva

© Anna Guseva

The images of the 1990s are rooted not so much in the conscious mind as in the body. I believe this is because I lived through that era at an age when I could not yet rationally comprehend what was happening, yet I perceived it acutely on a physical level. These experiences became encoded as bodily impulses. Some of these bodily “situations” or “urges” are even difficult for me to translate into words – I can feel and recreate them, but I cannot name them.

YN: When working with imagery tied to fear, violence, or trauma, how do you distinguish between documenting fear and reproducing it, and how, if at all, does the present political climate in Russia influence those decisions?

AG: Since 2022, I have not returned to Russia, and the entire project has been shot in Europe – in France and Germany. Initially, I searched for locations that might visually echo the environment of the Russian 1990s. However, I soon realized that for me, it was not about specific places as such, but about particular configurations of space that activate that familiar, childhood sense of anticipated threat in the body. Working this way allowed me not simply to reproduce or replicate something external, but to physically enter and experience states of anxiety, foreboding, unpredictability, and loss of control during the act of photographing itself.

© Anna Guseva

© Anna Guseva

YN: How did the decision to make this project emerge, and do you imagine the viewer as yourself, a generation shaped by the 90s, or someone without that lived experience?

AG: It is important for me to share this project with different audiences. Certainly, with those who lived through the 1990s and, over time, came to perceive that period through the lens of romanticization and nostalgia. But also with viewers from other countries, for whom this historical context is unfamiliar, yet whose lives may have been shaped by other social or political traumas that imperceptibly deformed their inner landscape. The project does not assume a shared experience. Instead, it offers a space for recognizing the mechanisms through which collective history penetrates private life and continues to operate even when the original trauma appears to belong to the past.

© Anna Guseva

YN: Has working on this project changed how you relate to your memories of the 90s, or how present those experiences feel in your life now?

AG: Completing the project did not lead to reconciliation with these memories, nor did it diminish their presence in my life – but I never approached this work as therapy. I continue to observe how that era keeps unfolding within me, in social processes, and in politics. The intensity of my reactions to certain symptoms of that time has not subsided.

© Anna Guseva

© Anna Guseva

Recently, I came across television advertising from 1994 – commercials promoting Cypriot offshore schemes and cruises from Genoa to Tenerife. I was struck, and could not easily let go of the sense of indignation provoked by the scale of social inequality. While thousands of people – professionals with higher education, much like my parents – could not find decent work and shared a single sausage for dinner, the screens cheerfully broadcast opportunities that were light-years away from the reality of most viewers. I don’t believe a definitive endpoint is possible here. Rather, this is an ongoing process of observation and recognition.

Yana Nosenko is a multidisciplinary artist and curator whose work explores immigration, displacement, nomadism, and familial separation — drawing from her own experiences and expressed primarily through lens-based media.

She has exhibited at the International Center of Photography Museum, Gala Art Center, MassArt x SoWa, and Abigail Ogilvy Gallery. In 2023, she was awarded a residency at The Studios at MASS MoCA. That same year, she joined the Griffin Museum of Photography as a Curatorial Associate and Exhibition Designer, where she helped co-curate and organize exhibitions, oversaw daily operations, facilitated artist talks and panels, designed marketing materials, and worked closely with visitors and artists. In 2025, Yana was appointed Director of Education and Programming at the Griffin Museum, where she continues to foster artistic dialogue and learning through exhibitions, public programs, and community engagement.

Before focusing on photography, Yana studied graphic design at the Stroganov Moscow Academy of Design and Applied Arts and worked as a graphic designer at Strelka KB, an urban planning firm in Moscow. In 2017, she completed a major independent project: the design of Mayak, a typeface inspired by Soviet Constructivist fonts of the 1920s–30s, later released by ParaType.

She holds an MFA in Photography from the Massachusetts College of Art and Design and a certificate from the International Center of Photography.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Anna Guseva: The Black Night Calls My NameJanuary 26th, 2026

-

Nathan Bolton in Conversation with Douglas BreaultJanuary 3rd, 2026

-

Jake Corcoran in Conversation With Douglas BreaultAugust 10th, 2025

-

Matthew Cronin: DwellingApril 9th, 2025

-

Jordan Gale: Long Distance DrunkFebruary 13th, 2025