Photographers on Photographers: Megan Reilly in Conversation with Morgan Gwenwald

Every August, we run a month of photographers interviewing other photographers, and we finish this month with interviews by our amazing interns. Megan Reilly was critical in making the Lenscratch Student Prize effort so seamless and we are so grateful for her time and energies. Today we share her interview with the photographer Morgan Gwenwald. – Aline Smithson

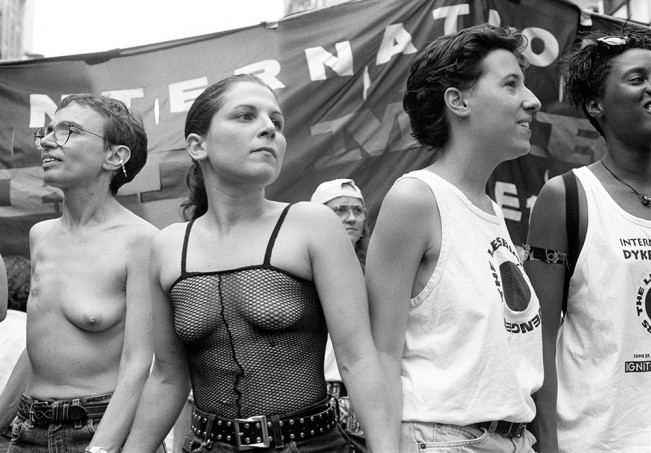

I met Morgan Gwenwald in May of 2019 when some of my classmates and I were asked to assist in curating a retrospective at the Sojourner Truth Library in New Paltz, NY out of some pages of negatives Morgan cautiously handed over to us, later titled, Framing The Invisible. I picked up those negative sleeves in awe of the images flaunting queerness before me. Looking at them felt like a bit of a homecoming, to see faces of the people before me that fought for justice and working with one of them in the flesh was an honor. The photographs varied between protestors on the street, portraits in the safety of a home, and many nudes of friends and lovers during the Gay Rights moment in NYC during the 80s. At the same time Morgan was preparing a photograph for Art After Stonewall 1945-1996 at the Leslie Lohman museum along with images by Robert Mapplethorpe and Diane Arbus. She holds one of the largest photographic archives of lesbians and queer people, yet I have only managed to get my eyes on a few and I am not the only one nagging to see more.

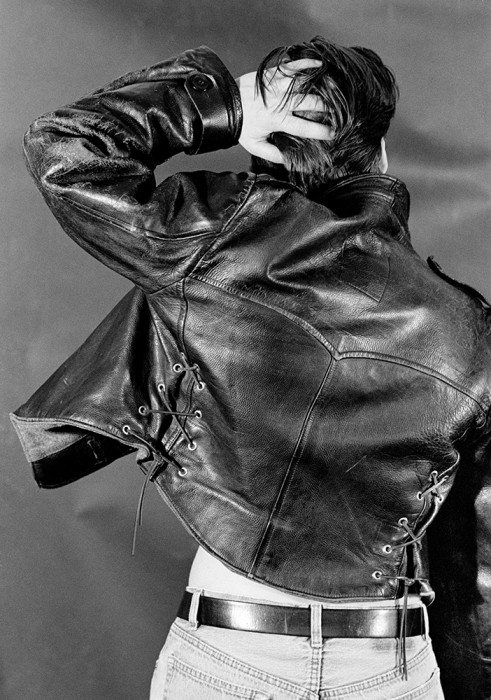

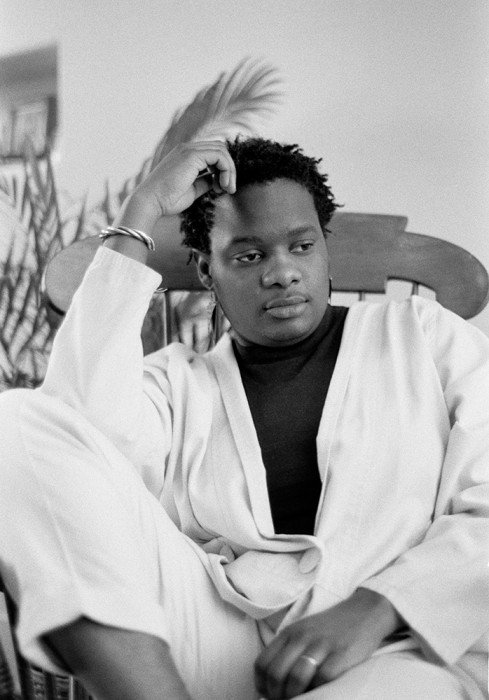

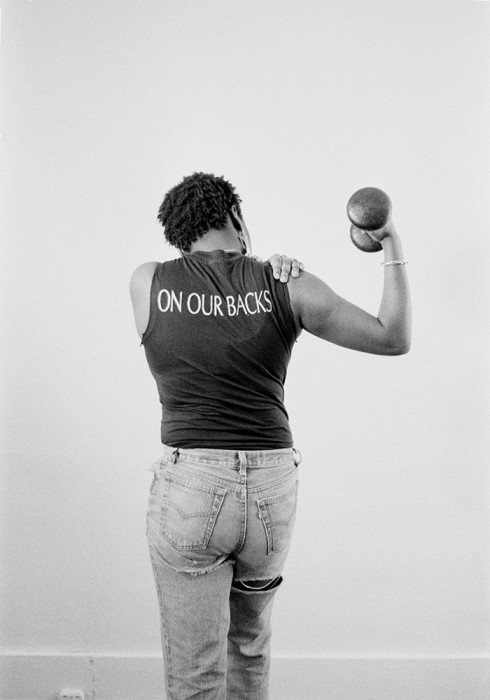

Morgan Gwenwald is one of a small group of lesbian photographers who emerged during the early days of the gay rights movement. While still in high school she talked her way into photography courses at the local college. When she graduated with a BFA she had a clear understanding that the world she wanted to portray was not welcome in the art world or the rest of the mainstream. This was a time of few “crossover” artists. The few working professional lesbian photographers were in the closet and the small but growing group of out dyke photographers worked primarily in their community. Gwenwald’s work has been embraced and well documented within that community of the 70s, 80 and 90s. In those years of a thriving women’s and queer press her art work was featured on many covers and her documentary work filled newsletters, journals and magazines of the era. Her goal was to show the world in which she lived and the women who populated that world visible in honest and loving detail. Her move to New York in 1979 and long-term involvement in the Lesbian Herstory Archives opened the doors to a broader community. Early on she took up the challenge of portraying lesbian sexuality in all its diversity and was one of the few to publish such work. (On Our Backs, Coming to Power, Stolen Glances, Nothing But the Girl).

Megan Reilly: You’ve created a photographic archive of lesbians and queer people experiencing the fight for respect, family, liberty and justice while using art as a secret cubby of communication. What brought you to the point of deciding to not only participate, but make art within the gay rights movement in NYC?

Morgan Gwenwald: When talking about my work as a photographer I find it so important to understand the context in which I was working. That is basically, the life I was living. I was drawn to photography as a young person, did some photo work on the h.s. newspaper and was able to take photography classes at the local campus, FSU, while in my last year. Coincidentally, the head of that department was a somewhat closeted lesbian (what are the odds!) I went to Florida Presbyterian College my Freshman year, not to be confused with a religious school, it was like southern Antioch, or New College across the Bay. I studied photography there with the curator of a local museum who taught the Zone System and classic B&W photography, which I loved. He gave me the keys to all those amazing images I had been looking at for years. My political and social life exploded when I returned to Tallahassee to earn a BFA. I turned my camera almost exclusively to the amazing world we were creating as feminists, lesbians, outsiders, activists. I was surrounded by amazing women and joined a community of friends, comrades and lovers. For decades my community formed the greatest part of my work and I left the academic art world behind.

MR: I recently met up with my cousin Susan in New York and we discovered that she is planning on working with the Lesbian Herstory Archives, where you were a coordinator and are a contributor to. We were stuck in between feeling shocked and astounded being faced with how small the queer community can be. The people we could reference and name, were from your images, continuing their travels through the New York queer community. How did these images begin to make their way out of your hands and into the public, even your erotic work?

MG: When I look at my march photographs I see the subjects looking directly back at me, with a smile, a smirk, pride, joy… whatever, we clearly “know” each other. I spent more than a solid decade documenting the queer community in NYC, at the burgeoning Lesbian and Gay Community Center, at the Lesbian Herstory Archives. I shot events for organizations, marches and protests, readings, concerts, practically everything I attended I photographed. And having a camera in hand gave me something comfortable to do so I didn’t have to be so social. It was an exciting time to be a young dyke in NYC. I published my work in newsletters, queer journals, books and participated in a few shows. In the early 80’s I started documenting the erotic in the lesbian world around me as well. I was one of the early out lesbian photographers shooting erotic images of women. I was aware that there was very little “real” imagery of lesbian sexuality and I worked to create a body of work that reflected the various joys and styles of woman on woman lovemaking. I have always considered this part of my work to be an intersection of documentary and art photography and highly political. Some of this work was controversial to others because it exhibited what some termed “politically incorrect” sexuality. I will never forget the Lesbian Sex Wars and how that fissure in my community left me distrustful of feminism. I felt that old suffocating feeling of being told how I was supposed to censor myself and how I should think to be a “good girl”.

©Morgan Gwenwald, Maxine Wolfe, Marshalling at Irish Lesbian & Gay Organization (ILGO) Protest, NYC, 3/16/96

MR: Photographers can be conveyed as a voyeuristic, always searching and sometimes scalping the world for imagery that does not belong to them, but your images appear to be at ease. You, the photographer, the people photographed, the atmosphere, appear to have mutual respect for one another, unworried with hierarchy. They seem to be in admiration and taken with consideration in a time where respect for a queer body was not relevant to many.

MG: I approached this work in collaboration with the models. My models were often my friends, sometimes my lovers, and occasionally women who just asked me to photograph them. None were professional models and I’d have an in-depth conversation about my work, where it might be exhibited and about what their consent could mean. Few photographers worked so hard to be honestly consensual. I let them see the proof sheets after the session and they had the right of refusal of any image. I remember one really wonderful set of photographs I shot of a couple only to have one of them back out when the contact sheets were in hand. Even without her face in the images, she felt she might be recognizable. Those beautiful images have never been shown. I have been criticized for having so many headless bodies… but that is what made it safe for many of my models. I also think not having a face attached sometimes makes it easier for a viewer to enter into an image in her imagination. This was during a time that unless you had access to a darkroom and knew how to develop and print film, you needed to send your negatives to a commercial lab. This was often risky, the FBI was always lurking in the background and it was impossible to safeguard the images unless you did all the work yourself. A camera in the hands of an outsider can become a truth-teller for freedom and a doorway into the dreams of a better world. The visualization of who we were and what we were doing fed me and broke down the isolation I felt in the first 20 years of my life. There was an entire movement of queer artists and musicians breaking down the walls of invisibility and demanding space to discover who we were, to be seen as we saw ourselves, not the pathologies they called us. In many ways our work is what we needed to do to survive. That has not really changed for the queer community. We are still discovering our individual truths and building structures and cultures to support them. I find it heartening that the growth just continues, new ways of being in the world are explored and shared, and are now photographed by EVERYONE. I no longer feel the need to document everything around me, it is being done by so many. I am also far removed from my people (living upstate) so I photograph my mother earth instead. Now I put energy into getting my images (70s-90s) scanned and out into the world in other formats and collections. Most of the publications that I contributed to no longer exist and were never collected by libraries, and are only included in a few queer archives. And sadly, as time passes I am asked more and more for photos for “In Memoriam” uses.

MR: I find it complicated to read “In Memoriam” as I am just learning and seeing these images, your people for the first time. They are all new faces, but ones that have contributed to the way that I live my life that I can be thankful for. Let them live on through everyone that feels that homecoming when looking at the images.

Megan Reilly is an artist and curator living in Athens, Ga after completing her Bachelors of Fine Arts at The State University of New York at New Paltz. She was born in Staten Island, NY and resided most of her life in the Hudson Valley. Megan works with photography and digital fabrication as a way to process and express her inner dialog throughout adolescence and into adulthood. You can find her on Instagram at @honeyp.ie.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

Ben Alper: Rome: an accumulation of layers and juxtapositionsJanuary 23rd, 2026