Photographers on Photographers: Su Ji Lee in Conversation with Kensuke Koike

“If I have many ingredients in my refrigerator, I can cook everything I want. But some ingredients may never be used. If I find only a carrot inside, I must cook it in the best way possible by chopping, grating, roasting, boiling, frying, drying, etc. With many ingredients I would probably never discover that the carrot itself can be such a delicious ingredient.” – Kensuke Koike

How does one come across non-archival photographs? There are boxes and boxes of strangers’ faces ready to be picked up in antique stores, flea markets, or even weekly garage sales. Though they might have been forgotten by one, it never goes discarded through Koike. With additive motion and revealed subtraction to the found images, strangers tend to warp, mutate, or remobilized. When I first came across his works in my freshman year of college, I was in awe to witness his treatment of guiding the viewers into possible lifeforms of still strangers, introducing a new paradigm to image appropriation. Through Photographers on Photographers interview, I had the pleasure to take a peep behind his curtain, a tricky visible world.

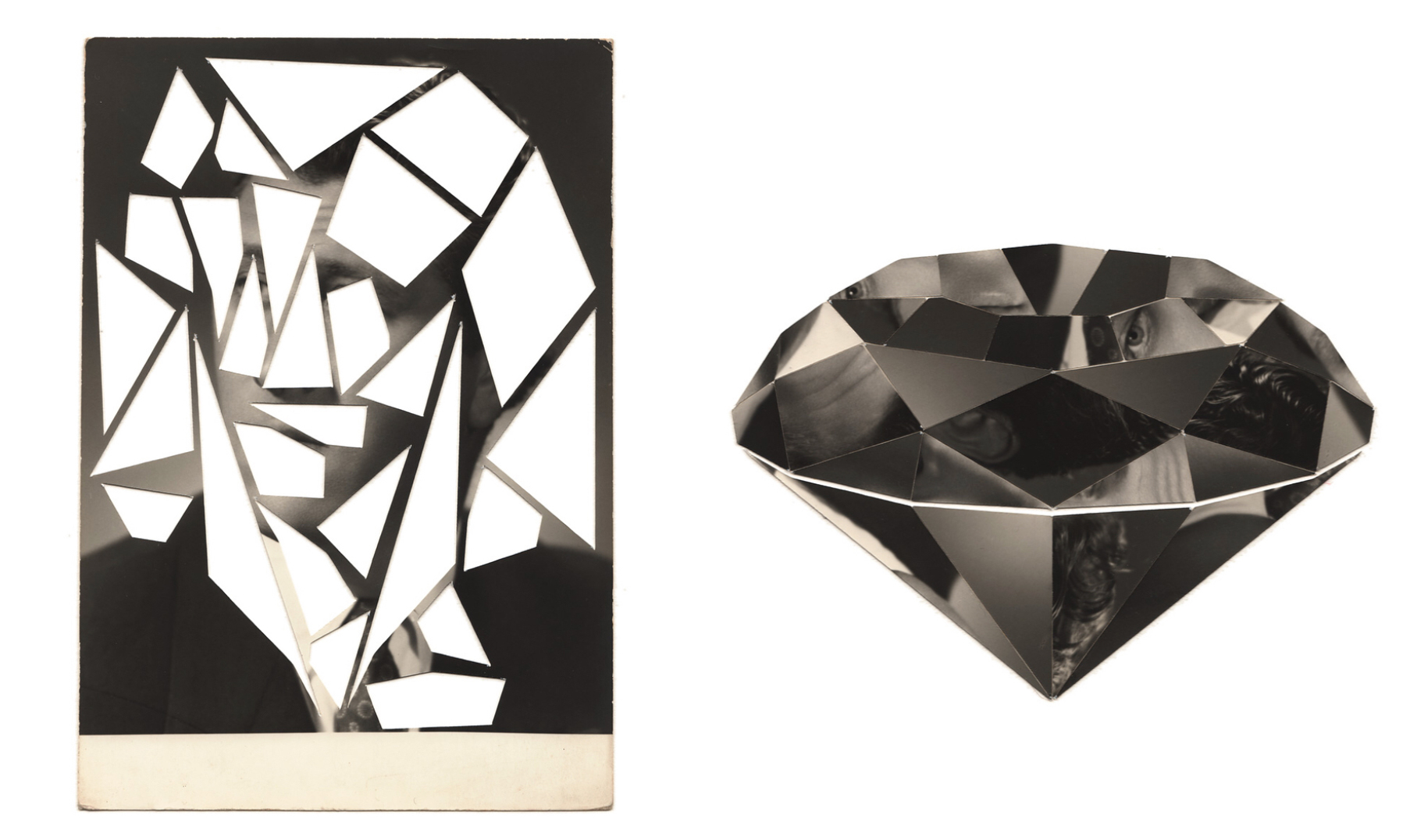

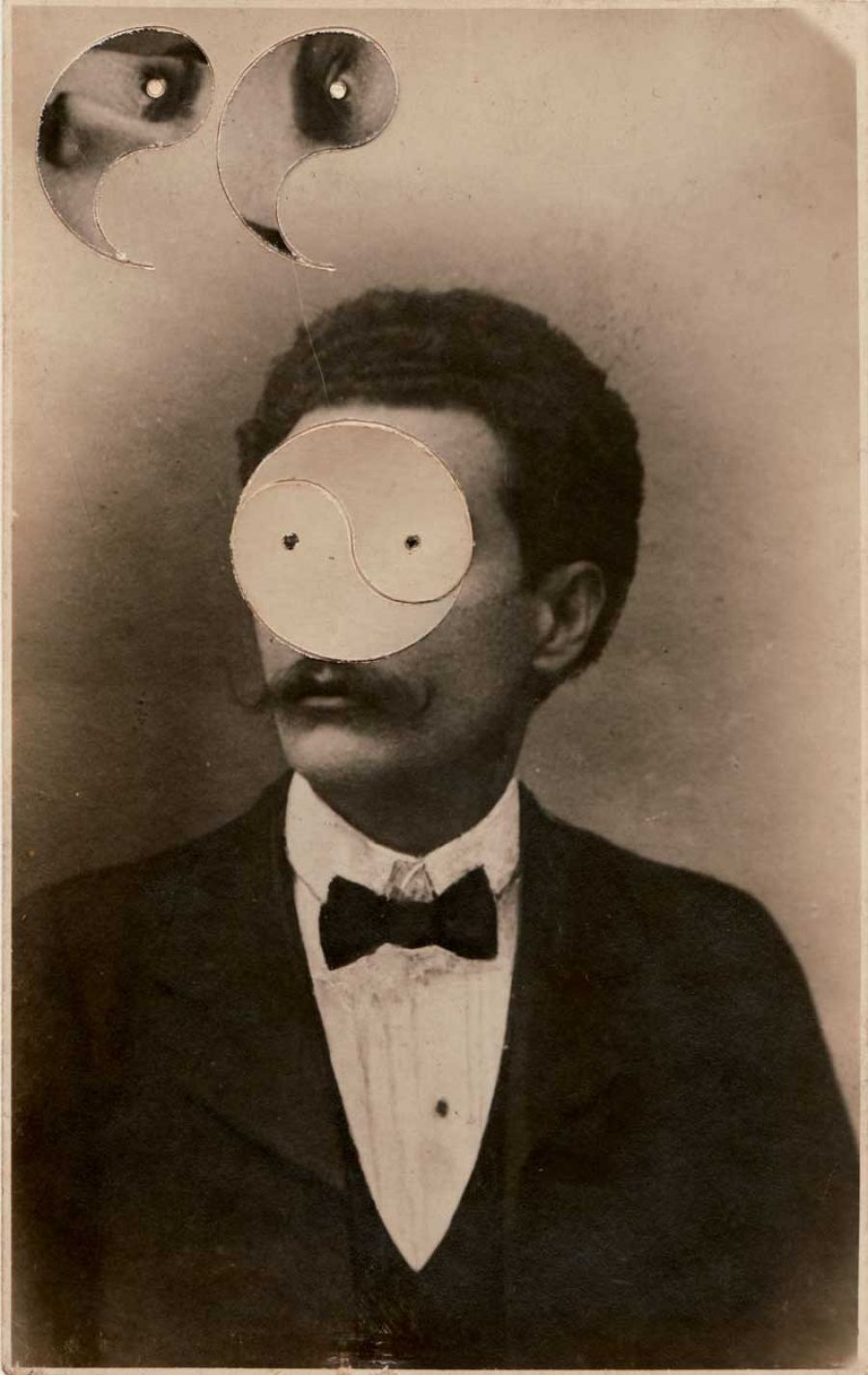

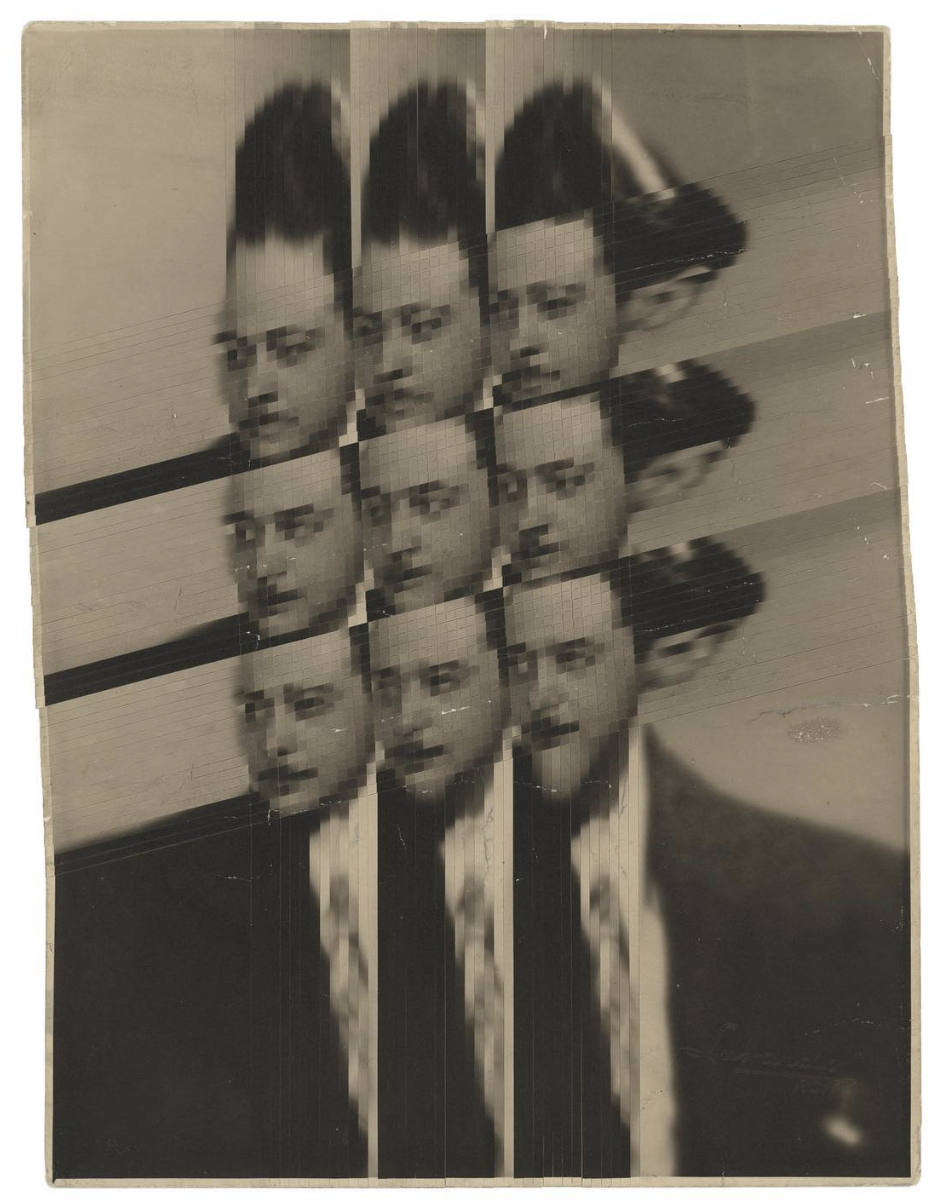

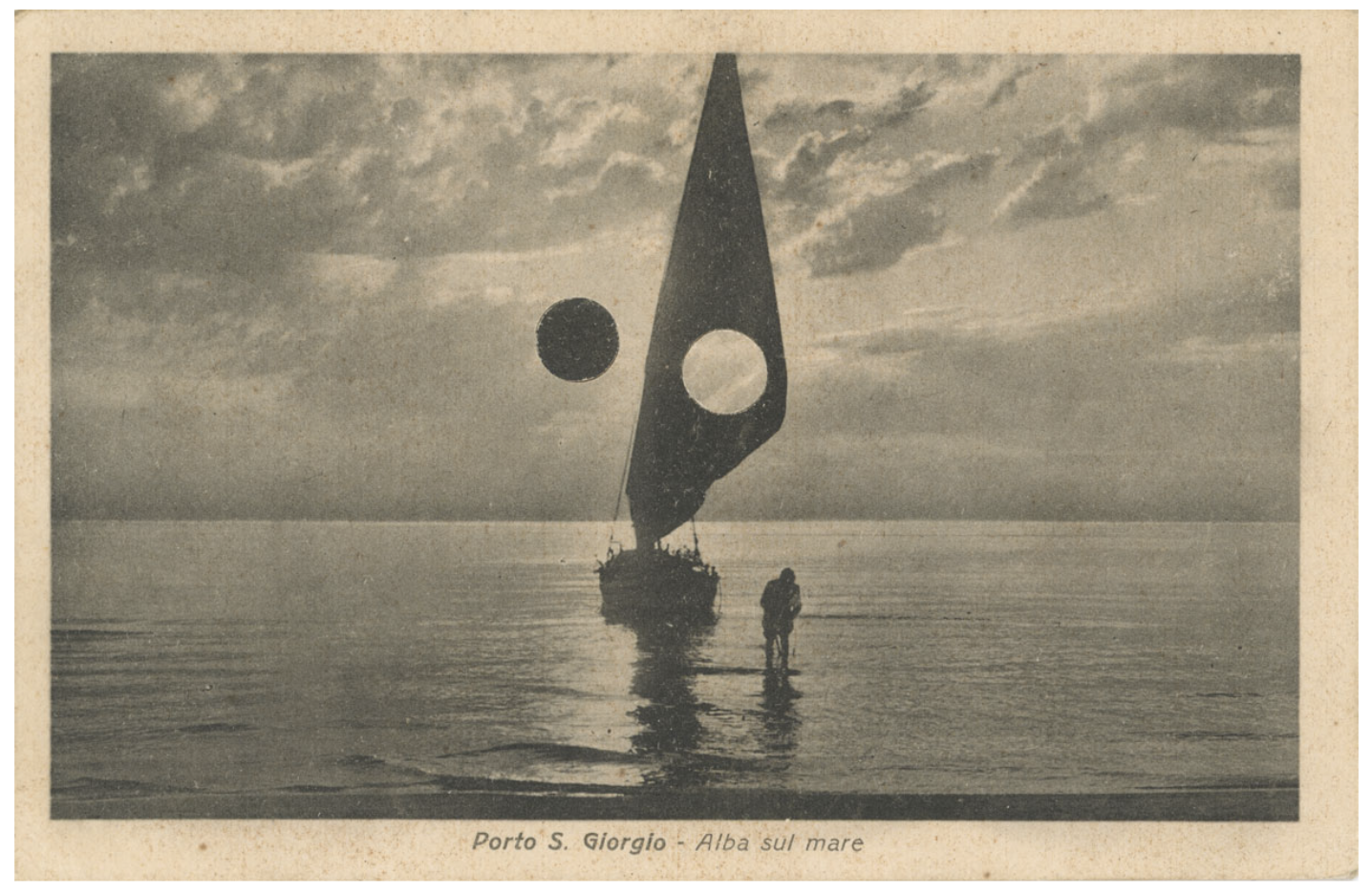

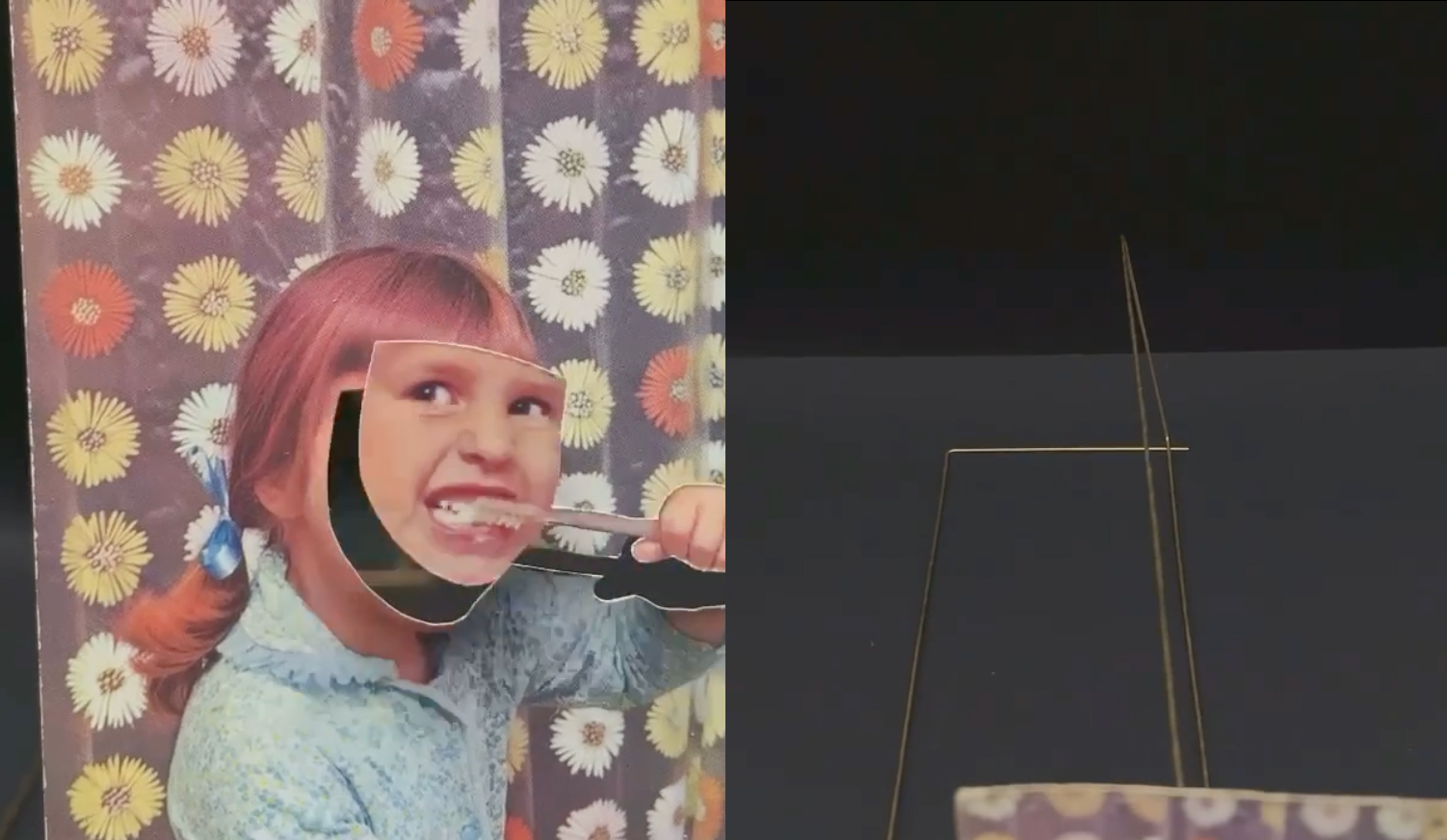

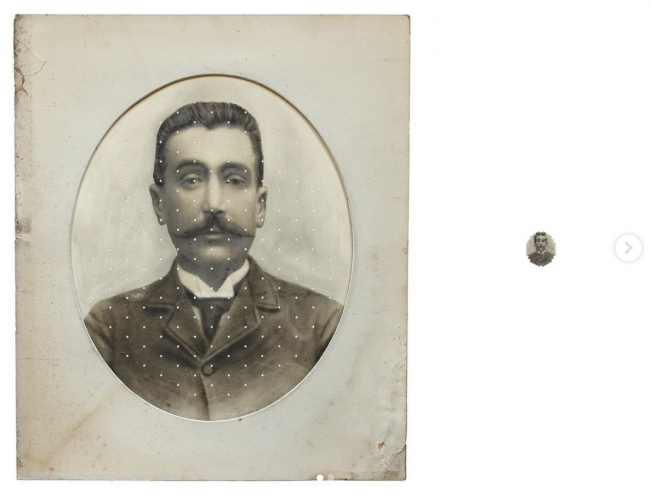

Kensuke Koike is a contemporary visual artist working at the intersection of photography, collage, and sculpture. In Dear Friend, Koike deconstructs vintage photographs or postcards to create new images by cutting, pasting and reassembling by hand. Many of his works visually transform in utilizing the approach of “nothing added, nothing removed,” by rearranging pieces and parts, into something completely reimagined. Koike’s eye for the surreal reinvents found imagery into surprising and delightful objects. His “renewed” photographs challenge the viewer’s expectations with new associations that reveal humor, curiosity, absurdity, and beauty.

Kensuke Koike (Japanese, b. 1980) was born in Nagoya, Japan and is currently based in Venice, Italy. Koike has exhibited nationally and internationally, including Postmasters Gallery, NYC, USA; The Photographer’s Gallery, London, UK; IMA Gallery, Tokyo, Japan, among others. Koike studied at the Academy of Fine Arts, Venice, Italy (1999-2004) and IUAV University, Faculty of Arts and Design, Venice, Italy (2004-2007).

Follow Kensuke Koike on Instagram: : @kensukekoike

Su Ji Lee: It is fascinating how you often present yourself as an alchemist. Can you tell us why?

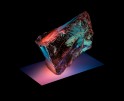

Kensuke Koike: I had a moment when I was researching how to make gold and diamond. To make a diamond, you need a big machine to make pressure on the carbon material. I was then very surprised to come across a memorial diamond where the family could transform a deceased body into a diamond. This sparked my curiosity about what kind of economical and marketable value difference these two artificial diamonds hold in our society. For them to be indistinguishable in plain sight, the amount of emotional engagement that went into the object is what makes the body diamond way more significant than the other. This feeling pointed toward my collection of vintage photographs that could become something precious, translating the physical pressure on an image instead of carbon.

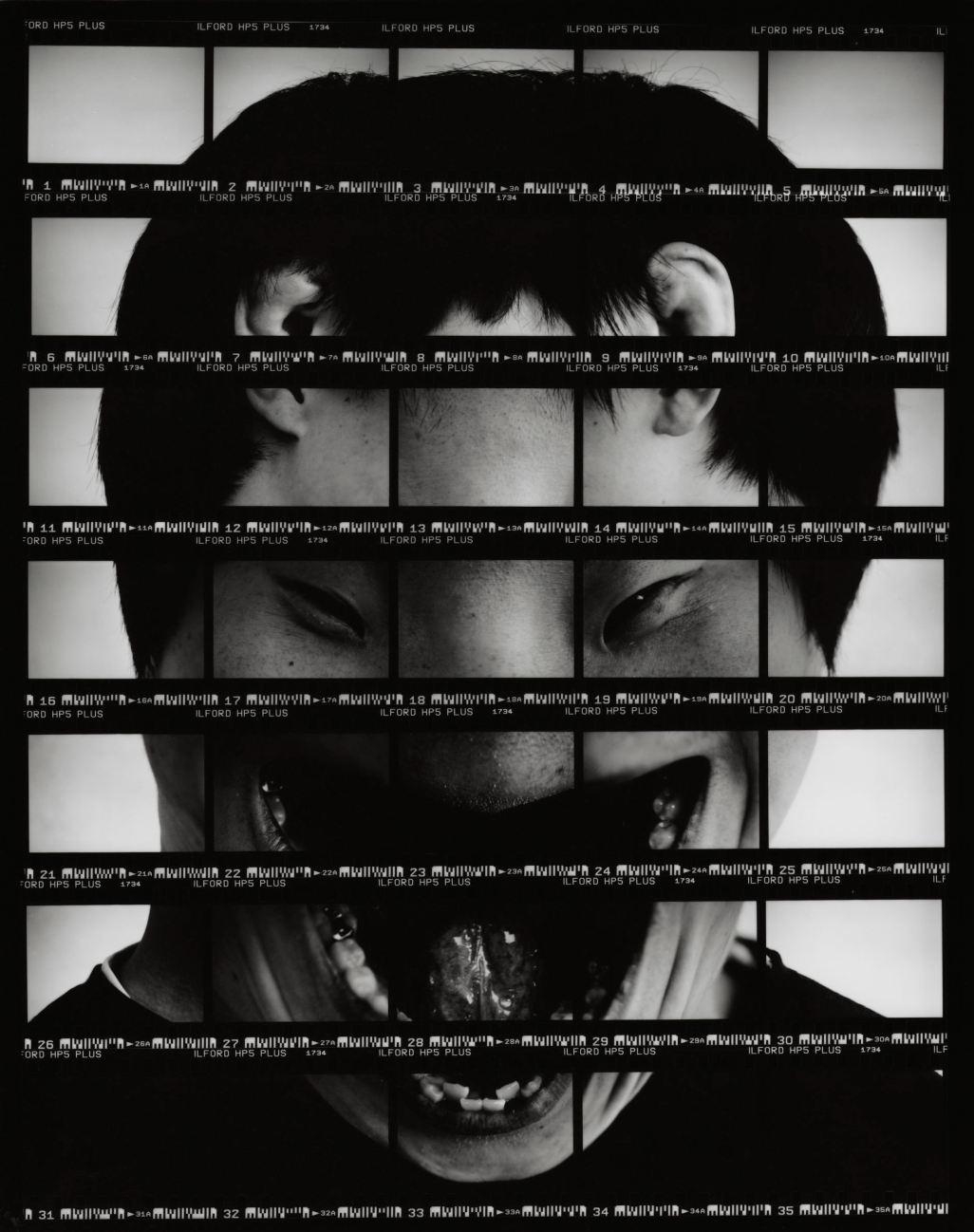

SL: Yang Yang, 2012 is the very first work of the Single Image Processing series. How did this project develop from here and where does your fascination with altering found images come from?

KK: I was shooting some analogue photos before I got my hands on vintage photographs. When I was passing by some flea markets, I bought a couple of abandoned vintage photographs for just two or three cents per image. These images were unwanted yet unique as their own, so I can constantly challenge myself to use something that I cannot make any mistakes or “undo”s.

SL: Your subject matters are in a wide range from babies to family photographs. Does staring at strangers and unfamiliar faces from different eras ever startle you? If so how do they inspire you to the specific alterations?

KK: It is actually in reverse where I first choose an image randomly and then contemplate what to do with them. I create prototypes with random images and begin to play around, to have a clearer idea of what kind of interactions are needed in the characters in order to take away the importance of the content itself, and what they offer through manipulation. I especially seek small interventions to make in human faces, for it to become a direct key for inducing foreign recognition. It has significant qualities that altering a landscape doesn’t fulfill, since you can barely recognize any difference once you are not familiar with that specific territory. Unlike landscapes, a slight rotation of the corner of one’s eye ignites eeriness that you instantly recognize.

SL: How did you get to perfect your technical skills for your ideal execution? It seems like loads of meticulous mechanisms are involved for even one arm to jiggle.

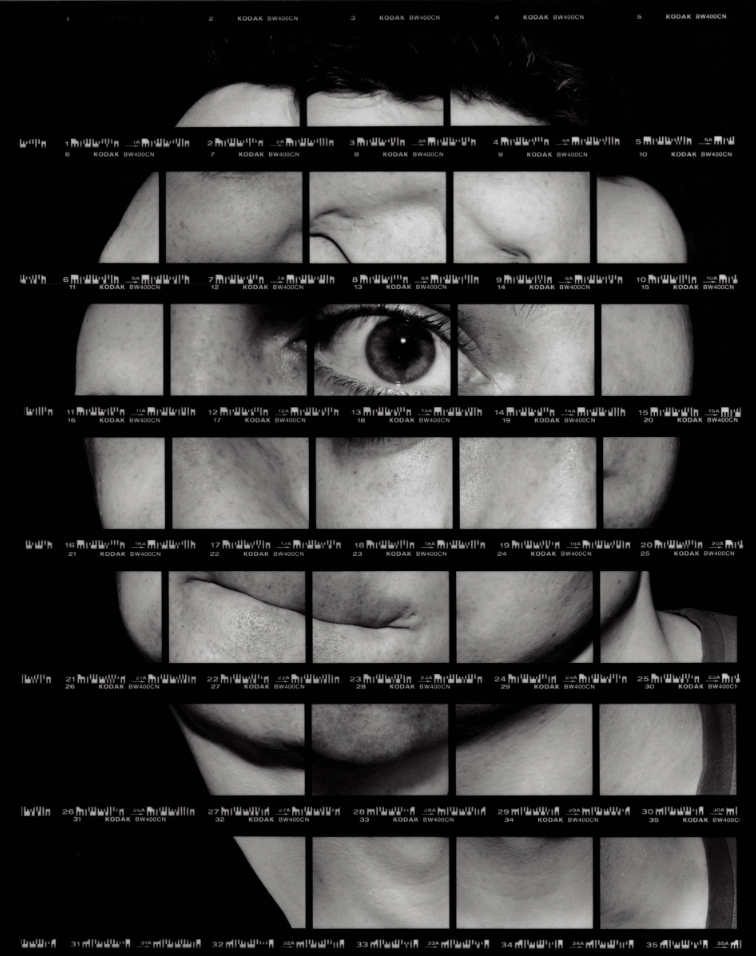

KK: Ah, yes. I can use this as an example. This is probably one of my biggest works (referenced above). I found a dirty magazine on the floor and now, they are in my possession. In order to make punctured images, I make a template that comes on the photograph. I also used a separate vintage paper that I also found in the magazine to create the miniature face with the punctured remains from the original image. So preparation is everything for me, especially with fake facsimiles that I could run through trial and error. Ten days of preparation and ten days of holing it down. It is quite stressful to think that I cannot make any mistakes because once you advance with a single mistake, ten days of your life vanish in a split second! I don’t even drink coffee the day before to prepare my physical body before the actual operation.

SL: You are a just like a surgeon!

SL: Since you majorly work with vintage photos, it was a nice surprise to come across your No One Knows contact sheets, where you viscerally utilize the structural value of contact sheets and manipulation of consecutive frames are inspiring. Did these come before your obsession with found imageries?

KK: Yes, this came up prior to working with vintage photos when I was showing my works to the Italian galleries. The collectors were more drawn to the analogue photographs, and that was when I gave myself the challenge to transform my playfulness to the analogue format by creating these two contact sheets. I simply wanted to show them that I can make something with analogue photos. So this is only, like a game to me.

SL: How did your creative brand, POLE & TOTEM come to life? They seem like one of your treasured toys, as opposed to works shown in galleries and an object that people could actually interact with and wear. Do you have any further plans for this project?

KK: Yes, I am actually making playing cards with a part of the faces printed double-sided. My attempt is to research the randomness of the images and when I shuffle the images. What will happen beyond my imagination? The random shuffling through the cards will give me much more information about what I can do and cannot see. For this, I can also make enough to distribute it to the mass because usually my works are usually kept by galleries and collectors. Actually, I noticed that my works do not always exist in a frame but in a box! This is very strange to think how sometimes people pull out my work from the box under the bed, check out my work from time to time, smile, and put it away. You can say that my real works are always hidden so I stride to distribute more from POLE & TOTEM.

SL: Is there a conscious way of thinking to sustain your passion and yourself as a maker?

KK: The most important thing is to know the know-hows. I sometimes have to revisit what I have done in order to activate it as I envisioned. When the original pieces are scattered all around the world, I look at my own videos to replicate the same movement and rekindle the technical mechanism. It is not so cute to say but I definitely am addicted to knowing much more things. I utilize both cards and vintage images to make my work but all these skills and techniques could be applied to the other mediums. So this is the most important thing for me that I’m not a “photographer,” since I do not take any photographs. But someone once called me a “paper sculptor.” So it all depends on what medium I choose to use. Now I’m making some puzzles. It might not be apparently connected to the images that I am making but basically is always the same.

Su Ji is currently based in Brooklyn passionate about photography, installation, and puzzles. Starting the photographic journey in Seoul, South Korea, her works focus on sharing experiences regardless of their residential disparity by demonstrating a series of visual queries with familiar objects. The still lives are controlled in a constructed environment where embedded order in beings gets complexed by human interventions. Taking advantage of the innate factuality of the photographic medium, the images exist as a form of evidence of the fabricated portion of the visible world. With an equal gaze to human figures and still life, Su Ji reassembles anonymous yet effable cues into a flat miniature.

Su Ji studied Photography and Museum and Gallery Practices at Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, New York. As the recipient of the 2020 Feature Shoot Emerging Photography Awards, Lee’s works were featured at the Aperture Gallery, New York. She is also the recipient of the 2019 and 2021 Made in NYC Photography Fellowship.

Follow Su Ji Lee on Instagram: @izzysqzy

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Jason Lindsey in Conversation with Areca RoeApril 21st, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: J Wren Supak in Conversation with Ryan ParkerApril 20th, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Josh Hobson in Conversation with Kes EfstathiouApril 19th, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Leonor Jurado in Conversation with Jessica HaysApril 18th, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Sarah Knobel in Conversation with Jamie HouseApril 17th, 2024