Photographers on Photographers: Sydney Walsh in Conversation with Sofia Valiente

This month we feature our annual Photographers on Photographers interview series. For this effort, we asked the 2021 Top 25 to Watch to share an interview with a hero, mentor, or an artist who has inspired them. Thank you to all who participated. – Aline Smithson

I came across Sofia Valiente’s book Foreverglades when my friend showed it to me while I was beginning my own work within my home state of Florida. It’s a unique object, containing photographs from modern times, embedded within a historical book. I always like to see how text can be paired with photography. Two separate entities made for communicating and storytelling, joining together to recontextualize a narrative. That is exactly what Foreverglades does. Then I learned that Sofia exhibited the work in a boat that was specifically made to replicate a steamboat from the pioneer times. The way she combined the past and present history of Belle Glade was thoughtful, well-researched and nuanced. The photographs were also accessible. After following her work for a few years and seeing how dedicated she was, I chose to interview her. We both grew up in South Florida and decided to tell stories within the communities there. I wanted to learn how she placed herself somewhere that was geographically close to home, yet environmentally, politically and economically a world away from coastal South Florida. I saw a parallel in her efforts and my own to slowly create visual stories over time. I was excited to learn about the patience, trials and tribulations that brought Foreverglades into existence.

Sofia Valiente is a photographer and storyteller based in Fort Lauderdale, FL. She received her BFA in Art from Florida International University in Miami in 2012. Her book, Miracle Village, was published in 2014 by Fabrica, where she had the opportunity of a year-long residency at their photography department. In 2015, she received the World Press Photo award for Miracle Village (1st prize, portraits, stories) and she is also a recipient of the 2015 South Florida Cultural Consortium Artist Fellowship and Burn Magazine’s 2015 Young Talent Award.

Over the past six years Valiente developed Foreverglades, a photo book and public art exhibit. This work, which debuted in November 2019, was supported through the Knight Foundation and the State of Florida through an Individual Artist grant.

She is available for assignment in South Florida and beyond. Her work has been published in Time Lightbox, Bloomberg Businessweek, VICE, the Guardian, Internazionale, El Mundo, American Photo Mag, Financial Times, Oxford Magazine, the Marshall Project, Quartz, Business Insider, British Journal of Photography and several other outlets.

Follow Sofia Valiente on Instagram: @valiente_sofia

Foreverglades

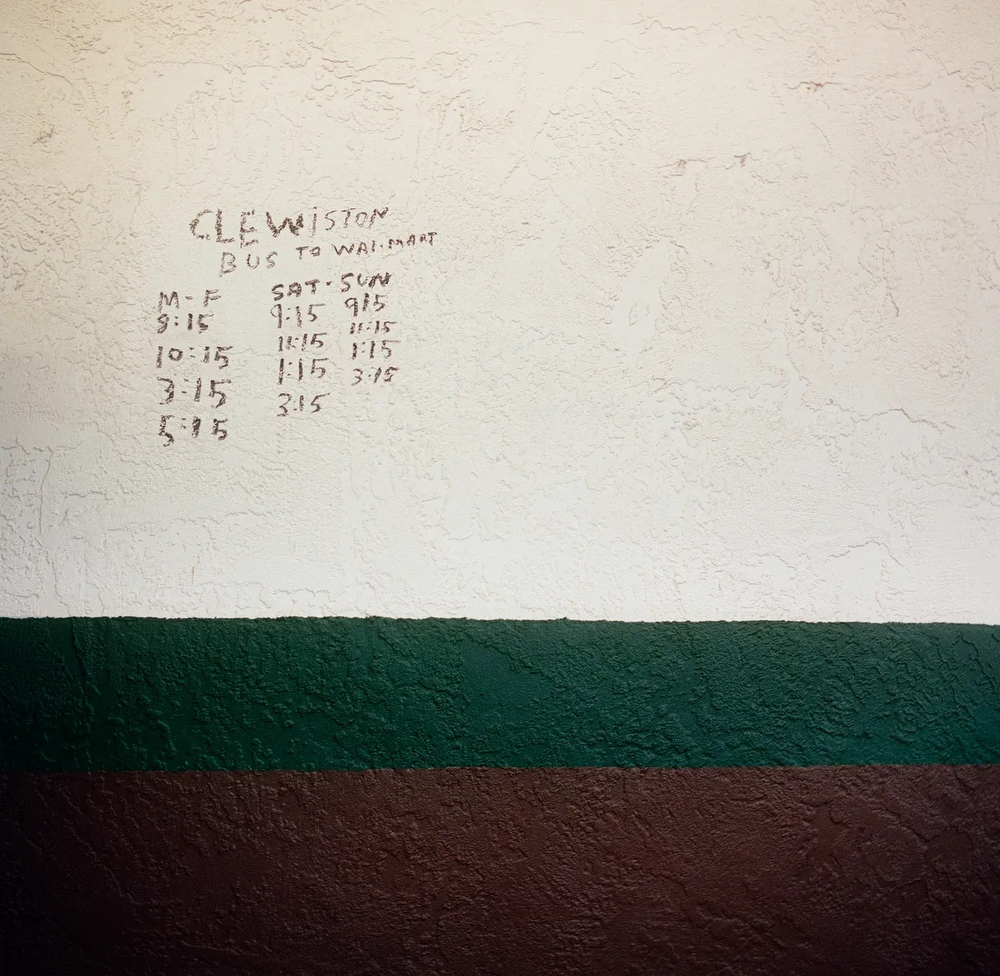

For decades after Western Expansion, South Florida was still a wilderness. Only once pioneers dredged canals and redirected the flow of Lake Okeechobee did this area become habitable. These once considered “useless” territories of marshes and swamps ultimately gave way to development and industry. On the southern tip of the lake lies Belle Glade, a small agricultural town that one might pass on a road trip today, just a couple of stoplights and it’s gone. It hides a rich history that leads to how we arrived here to Florida. In 2015, I moved to Belle Glade into a former rooming house apartment and soon after came across books by Lawrence E. Will and Zora Neale Hurston. Will painted a picture of the pioneers who developed the area through persistence and foresight, and for me, Hurston gave a voice to the workers who built the Glades with their bare hands. Their writing became my framework for exploring the past and looking at its contemporary parallels. In this time capsule, history is present. Roots run deep and the pioneer spirit can still be felt. -Sofia Valiente

Sydney Walsh: How did you come into photography?

Sofia Valiente: Let’s see. I was in community college in Broward and I originally wanted to go into film school, but I didn’t get into any schools. So I went to community college and I had just really wonderful professors who really empowered their students. And you know, I love the image for sure, I love movies, but I thought photography was just this thing that was really accessible. In school, that was basically my focus and I ended up getting a BFA. I love the community aspect of it I will say– but it wasn’t really until when I left school, after I graduated, that I started to seriously pursue work and devote myself to it. I think a part of that is also because in school you’re kind of limited, you’re stuck in a place, you know? I’m sure you know that. Which is fine because you’re learning in that space. You’re kind of being incubated there. I got the opportunity to assist some photographers while I was in undergrad and it really opened up my eyes. I think when you’re younger you put a lot of photographers on pedestals or whatnot, and you say, “Oh, my God, how can you be proud?” And you just realize how it’s very simple. You just kind of place yourself in a space and you just go for it really. Just the difference there is the commitment. How much are you willing to commit? And I was totally willing to go for it. Thinking back, I never thought I’d be making so much work about Florida if I were to ask myself when I was 20 years old or something. Because I had at one point run away to New York and wanted to drop out of school. But then I couldn’t, my senses and came back. Once I graduated, I was like, “Great. Let me go off, explore and see what I can find.” And really, literally, you know, an hour away from where I pretty much grew up most of my life there was this whole like– it’s incredibly rich, you know, with stories– this place, The Glades, the Western Palm Beach County area. I suppose I went on that road trip like “I’m gonna go explore” and then I just kind of totally stopped there. And then stayed there for seven, eight years.

SW: So what made you decide to focus on that area specifically? Why did you stop there and decide to stay there?

SV: Hm. Well, let’s see. I went up to this area, and it was a friend of mine that was doing movie stuff. He was like, “You should come see this area. It’s so cinematic.” And, you know, a lot of people actually go to that region. Have you been?

SW: Yeah, I’ve driven through. But I haven’t stayed.

SV: It’s otherworldly. I mean, it’s basically like you’re going into this time capsule. And I think, you know, a lot of where we grow up on the coast there it’s just like so transient, it’s development, development, development. And we don’t really have a good sense of what the trajectory of that had been, you know, historically or anything. So, here it was. This place that very visually brought you there. The really old buildings from the 1920s, the old character, and you know, a lot of that, and I was just really enamored by that whole scenery. I mean, I think everybody that’s a creative that kind of goes there has that same feeling, it’s kind of a mutual feeling. And anyway, and then I met somebody that ended up being my partner for a while, and he actually ran the small newspapers around the lake. And, he basically, he kind of told me that there was this community, Miracle Village. And right away, just by the idea of it, I was just extremely curious and just went there and things developed. That project was something that developed out of definitely, like, you know, I wanted to see what that boundary was. Such a wide subject matter that I really had no personal contact with. And then really, what made me stay though is the fact that it was nothing that I, that I kind of..my preconceptions were wrong, you know. It’s one thing to be curious and go somewhere, but another thing to be like, “Okay, this story needs to be told. I need to be embedded in this. This is worth it.”

SW: How has living there and making work there, and like you said, being embedded with the community, changed your relationship within that community and your relationship with South Florida?

SV: Well, I mean, absolutely, living in that region of the Glades in general, not Miracle Village, has absolutely taught me what we came from. The roots. Our roots. I think that’s just a really invaluable experience. Because that’s kind of what you do in life in general, right? You want to understand where you’ve come from. You usually do that with your family. But to understand a region that you grew up in and how that region has formed and shaped you in these kinds of subconscious ways. I think that’s just extremely valuable to do. And I’m glad I did that at my age that I did do that. Because it’s very foundational. It’s a foundation for me that I always will have.

SW: So you say it’s kind of the foundation that you had beginning your career in photography. How has it shaped where you are now in your career? Do you think it’s given you any opportunities that you wouldn’t have come into otherwise?

SV: I form my own path with things. I build my own exhibit and make my own book, just in that sense. I look at it more, as you know, it’s given me the foundation to really just understand America. And that’s very general. But I think it’s the closest I will ever come to seeing what it was like in the, sort of, pioneer days. And, you know, capitalism really, and, in essence, colonialism, and these sorts of things. And to very physically see it. See where. Because history has been very frozen there. And it’s just, it’s given me this really invaluable experience that I think when you grow up in a coastal area, or an area that’s like not rural, and you don’t really understand. You know, especially with all the divided politics and stuff. You don’t really understand why. You know, especially as a young person, why this is happening. Why doesn’t everyone want the best for everyone? Then you see that there’s a lot of these cultural and social, these histories there. And my research is really on the ground level. It’s like discovery. It’s like going through all the archives. It was just the whole experience of this 6, 7, 8 years living there was the research. It’s given me this really invaluable experience that I carry with me. I mean, ethically as well, you know, in terms of like, how I approached, you know, shooting things. It’s much more to me than photography. I mean it’s absolutely, it’s the whole journey of it, you know?

SW: Why did you decide to exhibit the work Foreverglades on a boat? How did you come about that idea? And what were some challenges you had? And if you were to do something similar like that, again, is there anything that you would do differently?

SV: Um, okay, differently, I’d have more money. Because it was like, this massive, I mean, incredible what a journey that was honestly, on its own, to create. The idea came about with one of the people that I met. He would collect all these sorts of old engines. And we just got into this conversation. Like I always do, people show me their stuff, and I look and I’m always interested. But he had told me the story about that stuff, that pond where I put the boat that it was, it was basically an inland port in the 1920s. It was called the stub canal turning basin, it’s still called that. But that’s where basically steamboats from the Glades, which obviously the power hub agriculture area of the South, they would get the the goods once they harvested– vegetables, etc. And put them on the steamboats from the Glades, and travel back then, before major roads were built, was done by canal, because obviously Florida was sort of was like, Florida was pretty much underwater. So close to some coastal areas. So that was really interesting. An important part of my work to understand that history. But anyway, so I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be incredible to basically have a steamboat in the stub canal there?’ Which is like downtown modern West Palm Beach. That juxtaposition of this really modern thing and this really old historic artifact. Which is the experience I wanted to give also to the public, the same experience I had in the Glades. Which was finding these artifacts, diving into history. And so I wanted to give that to the public as well, this feeling of going back in time. Then the story fit perfectly because it was, it used to be, you know, Florida, we have all these retention ponds, like thousands of them, which are basically just like these ponds that are built by, you know, by code, basically, because when you build a community or we build a building, etc, you need something that you need to build drainage. So when it rains are over, you know, so I just thought it would be so incredible to like, kind of activate this pond, which is not where boats go at all. So I had to put it in with a crane and it was the whole thing. But just like to, you know, for us, I grew up in Florida, you know, there’s a tremendous history there. And then I definitely knew I wanted to give an experience that was a more multi sensory experience. And one that wasn’t a traditional white box, you know, like a gallery, etc. Once I heard that story, I was like, ‘That’s it.’ and then I just spent some years making that happen. The steamboat was actually a replica of one of the last steamboats operating on Lake Okeechobee. So it’s based on that.

SW: How did you replicate that? Did you commission someone to build it?

SV: Oh, yeah. So I got grants. I mean, how do you build something like that? Right? I was really passionate about making it happen. I basically started researching boat builders. And obviously, it’s so expensive and just so many different people I would speak to, and I finally came up with the idea of how to build it. This is a very simplified version of all the trials and tribulations I went through. Anyway, I eventually finally got started working with a person named Mike Chapman. And he is amazing. He used to work in the cruise ship industry. And he would do project management stuff. He would build these incredible models. And he still does, like really intricate, really nice models. And basically he built me a really amazing model but large. And it’s super beautiful. It’s in Belle Glade right now, if you ever want to see it during the week, because we donated it to the city. So it’s there permanently. And the hours are kind of funky. If you go there’s a little museum there called the Lawrence E. Will Museum where City Hall is. And you’ll see the boat there.

SW: I’ll definitely have to check it out. That was gonna be my next question, where is the boat now?

SV: Yeah, yeah, it’s there.

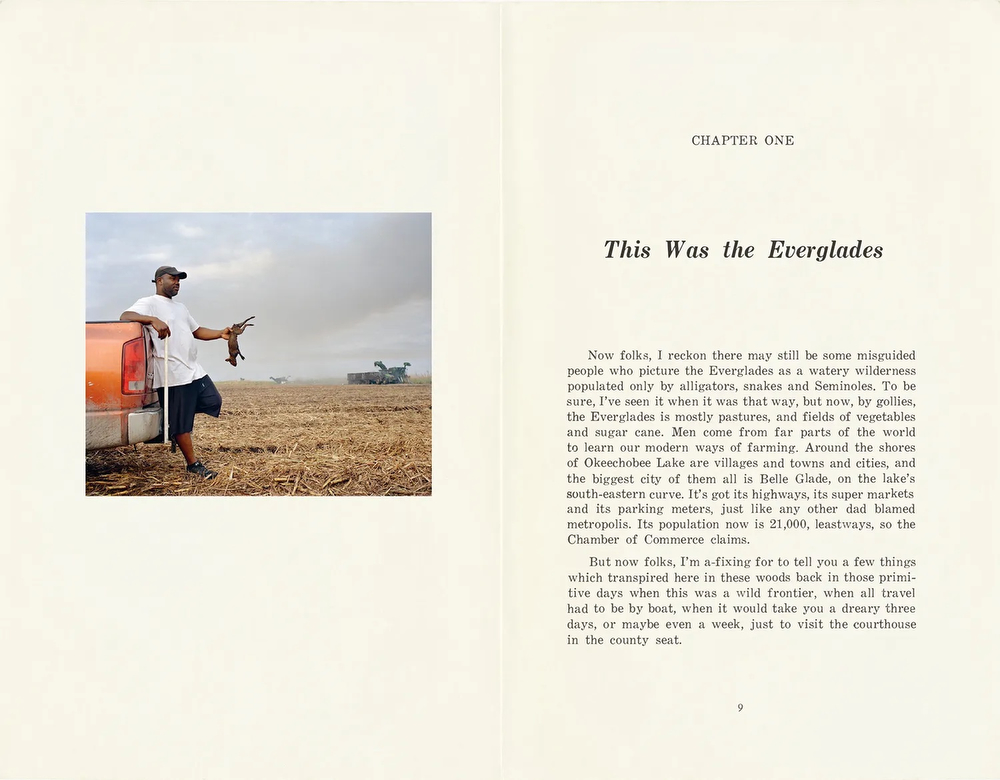

SW: So for the photo book, part of your work, how did you come up with that idea? Because I saw that it was kind of in a more traditional text-heavy book. Like a ‘normal’ non-photobook would be. And you put the photos in it. How did you come up with that idea? And what was that like making?

SV: Yeah, so that pretty much right away. The first year I was living in Belle Glade, I found somebody on a bike, who is a really, really interesting guy. He came up to me and he started talking to me about, oh, you know, this book that had these burning bodies. This image of burning bodies inside of it. And said, “My grandfather passed it on.” Anyway, he brought me the book, but it’s kind of an unknown Lawrence E. Will. That’s what that little museum is named after, the one where my boat is. So he was one of the first pioneers to survive in the area. And he was the author of that book. He was one of the first pioneers to write about their area, right when there were just a handful of people. And then he started collecting everybody’s stories and artifacts, and just so many handwritten accounts of people and he wrote a series of books that was about the history of the lake. And that one book was specifically about Belle Glade. So I was kind of enamored by the idea of this guy, because well, he was like, my unofficial kind of ghost guide there. What I like about that book is that it’s, obviously, historic, but it’s written in a very informal, spoken way. Everything in that book, it’s there for a reason. I would spend time in that museum too looking at the archives. And I just thought, when I first saw that book, I thought, “This is perfect.” You know, “This is the text for the book.” I didn’t know how it was gonna work out. Obviously, it’s complicated once you go to design. It’s a small book. It was funny, because I was like, “Okay, I really sacrificed a lot.” But, you know, in the end, what’s more important was having that text in conjunction [with the photos]. So that’s really what a lot of the photobook project on its own is. It’s a book about the contemporary parallels of that book. People that he wrote about years ago, I have photographs of that generation today. There’s like two parts of the book, there’s that text heavy part. And I really redacted a lot of that book, and I just really picked what could best tell you the history of that region, and the stories and some of the attitudes and made parallels. But in the center of the book is the part where I lived in downtown Belle Glade, which was a pretty rough, dangerous area. It had a lot of issues. But the story of me living there, it’s kind of a wild one, too, like I couldn’t really find a house to live in, because there’s not a lot of housing there. And so I ended up living there and I was only gonna live there one month, and I just kept living there forever. Anyway, the center of the book is basically my neighbors. Pretty much everyone is my neighbor, because it’s a small town, you know. But, that center, that heart of the book, are those people that very much lived within my vicinity. The relationships are a big part of it. When you live somewhere, there’s a strong accountability of what you’re doing. You’re out and you take pictures. You also live there. So you’re playing the role of the photographer, but also a community member. It’s much more than the photography. I was extremely conscious about what I’m doing and who I was around. And there’s a whole kind of a subconscious sort of sign around that. I really maneuvered and specific parts of the community became my family.

SW: So did any of those community members that you’re friends with see the finished work? Or even just a photograph that you made? Or the book itself, or the boat too?

SV: Oh, totally, yeah. So it’s donated [the boat]. Where it is right now is like three blocks away from where I lived for six years in that little apartment. It’s very much right in the community. It’s so funny, because, well you know, shooting film, I would get pictures a lot of times when I’m photographing the parties. And I have more photos in the boat than in the book, because the book, obviously, is limited to what you can fit. But I would always give them all the pictures. And I was also shooting medium format film. And a lot of times they’d want a picture and I didn’t have a digital camera. And I’m like, “Alright.” It was just so much money. But I would always, always, always do it. Because I also felt like, of course, like I loved it you know. There was an emcee at the Jamaican parties and they’d always be like “the camera lady!”

SW: Hahaha, “the camera lady.”

SV: It’s such a small town. It was so tight knit. Everybody, whether you are a farmer or a farm worker, everybody is so intertwined. I love that about it. That’s something I deeply miss now. It was very much totally about, I mean, it’s so hard to explain. I’m like, “Yeah, I’m gonna do this project.” And I even showed them. I always wanted to do something that was kind of transformative. And also the idea to bring the boat there, the work over to West Palm Beach. So, you know, there’s a big separation even though we’re in the same county from West Palm. And there’s a lot of trash talk about the Glades and it’s not painted in a great light. And so I wanted to really just bring the stories and kind of counteract the stereotypes and bring the communities together essentially. That was really my hope, my biggest hope of that. And I think very much did. I mean, had all sorts of people go to that exhibit. I think it was amazing when it’s all said and done, everybody that was a part is so grateful. I think it’s like I made a new history book with them and they were in a boat and I had these great parties for when I opened the boat. And everyone came out and it was amazing. Amazing. I mean, in terms of like, you know, how do you build a community? How do you build that dialogue around work? You can publish work and, and okay, people see it and that’s great. And whoever subscribes to that publication sees that. And that was like my first major experimentation, like, how do you build that dialogue, and it was awesome, because it was in a park. And during the day, on the weekends. The vibe was like, come hang out. And everybody has a story that they want to contribute, and then, you know, everybody gains something different. And I think that’s just a win. I mean, there’s other ways you can build dialogue, and the book does that in one way. And then the boat does it in another way. And then, you know, if you publish a portion of it, it does it in another way. But I think the ultimate goal was, how do I build something authentic here with the communities in the end? I’m grateful for it. It will always kind of be there and as like, just for things that have come full circle like that.

SW: When you initially started this work, were the people you photographed pretty receptive to, kind of, an outsider going in and photographing their community? How did you explain what you were doing?

SV: Nothing. I said, “I’m gonna be here. I’m your neighbor now. So you’re gonna have to put up with me.” You put in that time, you give all that to somebody, it’s like, eventually okay, well, this is not random. This is not a quick like, you know, this person is in for the long haul. So it’s kind of like, you’re not getting rid of me, you know. And I wasn’t like picture picture pictures all the time. And there were a lot of ethical questions every time I walked outside the door. I mean, this area, it’s an area that’s extremely troubled. There’s a lot of poverty in this one part where I was living. And that does hit you in the face every time you walk out the door. So a lot of constant ethical questions about what’s important, and why am I doing that? You know, how am I being a part– and I think that was really important for me, how can I be a part of this community? Because I think that’s in general, what I like. Obviously, the story is interesting, that’s the thing that guides you, but ultimately, what makes you stay is like, what are you building? And I don’t come from the time of when there were a lot of magazines always publishing your work. I think maybe that era is more of like, okay, go get photographic. And I’m like, okay, how do I build something that’s authentic? You know?

SW: So how do you sustain work like that in your career? It seems like you’re more interested and invested in doing longer term work, and really embedding yourself with communities and getting to actually know the people you’re making work about? How are you able to do that? Financially and also, mentally and emotionally too?

SV: I mean, you know, we need to figure out ways to fund work that’s not traditional anymore. And for me, definitely grants. Grants were very helpful. But not like the really highly competitive photograph grants. Because unfortunately, you know, those are great. But it’s hard. There are so many great projects out there. If you really want to make something happen, you have to find a way. I got some great grants and pretty big grants. Actually, there’s the Knight Foundation Grant. And they gave a significant amount of money for the book and, and then the boat. I got like $75,000 from them. And then I built off of that. I got grants from the state, the artists grants. But then also, because that’s not enough, we were building a boat, I started sort of like this thing of approaching people with money. When you’re making a project about a community, and you’re telling the community, there’s definitely business owners, there’s people that would want to contribute to that. Especially when you’re making a free exhibit. There were a lot of projects I had to raise money. One of the first ones I did was this sort of side project, that was this guide to the area. I did these portraits and interviews with certain community members that were pretty significant in the field of medicine and in different philanthropy efforts. And people that have published a book. I would pick these sorts of characters and I had a portrait and a photo, and then I sold sort of, kind of, ads, essentially. In that same format a magazine would do. I approached a lot of the local businesses and that was definitely work, but, you know, they supported me, and it was really wonderful. It was really neat because what I did is, you know, they had roots in the area and so I would tell little stories in the ads that were pretty neat. So these little storytelling mechanisms. And that was great because that was a wonderful little free publication I made that was distributed for free everywhere around the area. Everyone loved it. And it was in congruence with what I was doing for my own work. So, that was a great project to do, I think that helped. And then also, with the approaching other people, when it came time for the boat, I just knew in my heart that it was such a massive undertaking. And I thought definitely, there’s people that would [support it]. Why wouldn’t people want to support this? Because you don’t think about taking the initiative to do that. If there’s a grant you can definitely take an initiative. And don’t be shy, if this is something for the community, to say that you can’t do it alone. I’ve definitely worked a lot with different partners along the way. And I supported myself with the grants. You can allot some money to pay yourself. It was also a very inexpensive [place to live]. My rent was $350 a month. Which is just like the water bills. But I was shooting on film, I paid all this, you know. It was all paid through grants.

SW: What, or who, are your influences?

SV: The whole history of photography dating till now. That for sure. And then also, movies too. Actually, movies a lot. I love old movies, classic films, those are inspiring to me. I remember for Miracle Village, I was really obsessed, I love this movie called “The Beauty and The Beast”. That was the 1930s or 1940s version. It was a black and white version of the movie. Shot incredibly, beautifully, by a surrealist filmmaker called Jean Cocteau. Just amazingly sharp, also very beautiful, with lighting, etc. But the themes of the movie were amazing, too, and very simple. Talking about being a monster and having this label. I really connected with that. And at one point in the movie the beast asks, “You’re not fearful of me?’ or whatnot, and the girl says, “I’ve known worse men, but they just don’t look like you.” I had to put that quote in my book. The surrealist films, I love a lot of classic cinema, anything on the Criterion Collection. I’m really interested now looking at video art and work that goes into the psychological space of the subject. I’m really interested in Khalik Allah, he’s great. He’s photographed in New York City in Harlem out on the street corner in the middle of the night with a really shallow depth of field. But he would record as well. He would video. And it was really so poetic and elevated the subjects. I’m always more interested in understanding how we can connect with the subject, on humanity. Not how that subject is the “other” sort of thing. “How are they not the other?” is something that I think more on and on and on. I lived in the community, that’s the “other”, but then I found a way to connect. So I think that’s central to me. But anyway, that was so great because it gets you into that mental space. I think I’m more interested in that and understanding the XYZ is of the story. I don’t have that kind of journalistic mind. I’m influenced a lot by the history of photography during the Great Depression, the FSA. So some of them came to Belle Glade. Marion Post Walcott, she photographed, and she actually photographed in clubs as well. And so it was really interesting. For a while I was so obsessed with making the modern image of that. Because it was very much like you were looking at those pictures, the scenes that you’d find in Belle Glade. People on the porch, farm workers, tattered clothes and coming home from work. Those scenes that were so symbolic of that time, the Great Depression, and this wonderful archive of photography that’s a national treasure. In the beginning I bought tons of books. And I was obsessively trying to understand what that was and photographs from that time. You know, the Dorothea Lange time. I was definitely influenced by that as well.

SW: Do you have any advice for younger photographers or people who are just starting their photo careers? Any important lessons that you’ve carried with you that you would want to share?

SV: If you want to have a career in photography, just do it. Do the thing. There’s not an easy kind of, I think in arts in general, it’s always been hard. But I think photography has always had maybe probably an easier time of getting inserted, because there’s a field and a need for media and imagery, etc. But I think you have to be definite that’s something you want to do. I think if you’re looking at it from a job perspective, it’s like, maybe you find a job. Like you, you’re working at an internship, that’s great. So it’s just kind of like, I don’t know, I work from a place that’s different. It’s like, my personal projects, it’s personal work. And so I can tell you, if you want to make personal work, my advice is there are resources out there that aren’t the typical ones that you can pursue to help support your project. Partnering with nonprofits, this is a huge thing that we should tap into. There’s a whole field around that in America and abroad as well. So there’s a lot of ways, and people that would want to support what you’re doing. Just kind of get out of the box and maybe not follow what you think you’ve been told because none of that matters. At the end of day, what you want is to make, give birth, to the work. If you just pursue. And you have to not worry about those kind of things that are signifiers of success. Just keep at what you believe in, because that’s your whole purpose in general. I think always following your own path. I’m a big champion of that. Because you’re going to be developing your vision as your own thing. So be influenced, but always keep in your own way.

Sydney Walsh (常娇) is a visual storyteller born in Changsha, China, who grew up in and is currently based in South Florida. She believes photography is a vital medium that removes language barriers and universally personalizes history. As a human being and photographer, her work strives to be representative of the people she collaborates with in the midst of a world overflowing with misrepresentation. She uses photography to create records of light and tangible memories that are honest and intimate. Her work explores how culture, history and place affect personal identity throughout time. Raised by two chefs, a dancer for ten years and a musician for eight years, she uses these experiences in her vision as a storyteller. She is currently a Photo/Video Intern for Miami Herald.

Follow Sydney Walsh on Instagram: @sydneywalshphoto

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Martin Stranka: All My StrangersDecember 14th, 2025

-

Interview with Maja Daniels: Gertrud, Natural Phenomena, and Alternative TimelinesNovember 16th, 2025

-

MG Vander Elst: SilencesOctober 21st, 2025

-

Photography Educator: Josh BirnbaumOctober 10th, 2025

-

Aiko Wakao Austin: What we inheritOctober 9th, 2025