Contemporary Approaches in Historical Processes: Brian James Culbertson

How does modern alternative process differ from traditional uses of historical process? This week, all of the artists that we are featuring use historical processes with very contemporary approaches. Some of the artists alter the chemistry. Others combine their chosen process with other techniques, not only breaking the rules but opening up more possibilities to define contemporary alternative process.

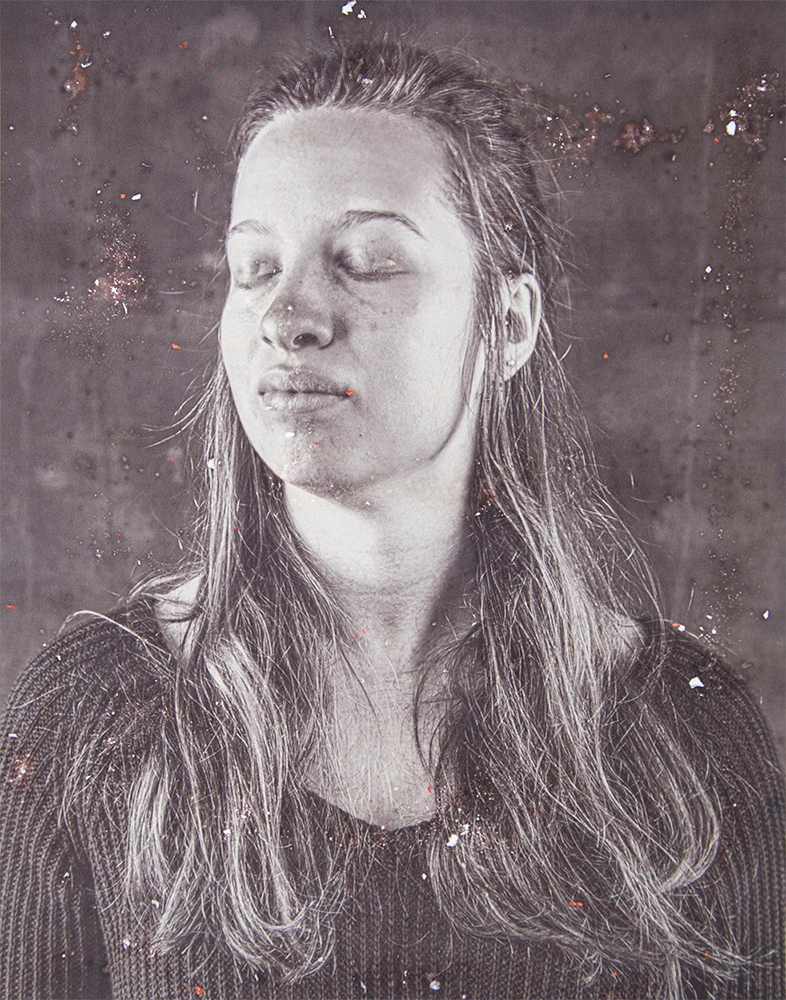

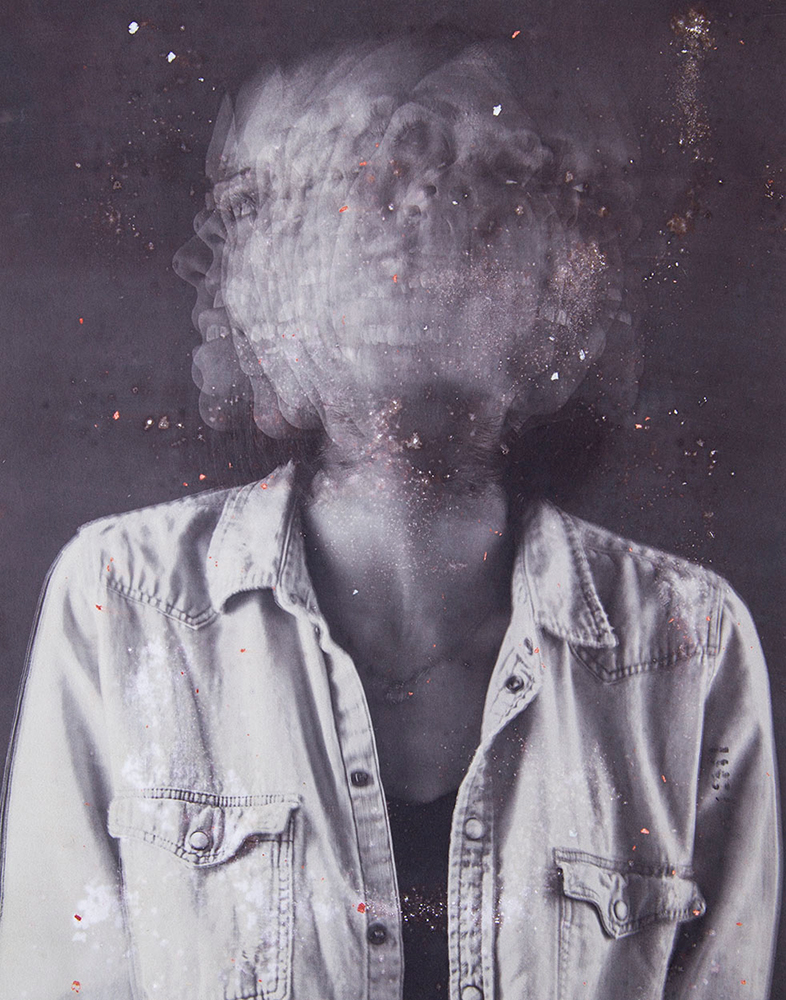

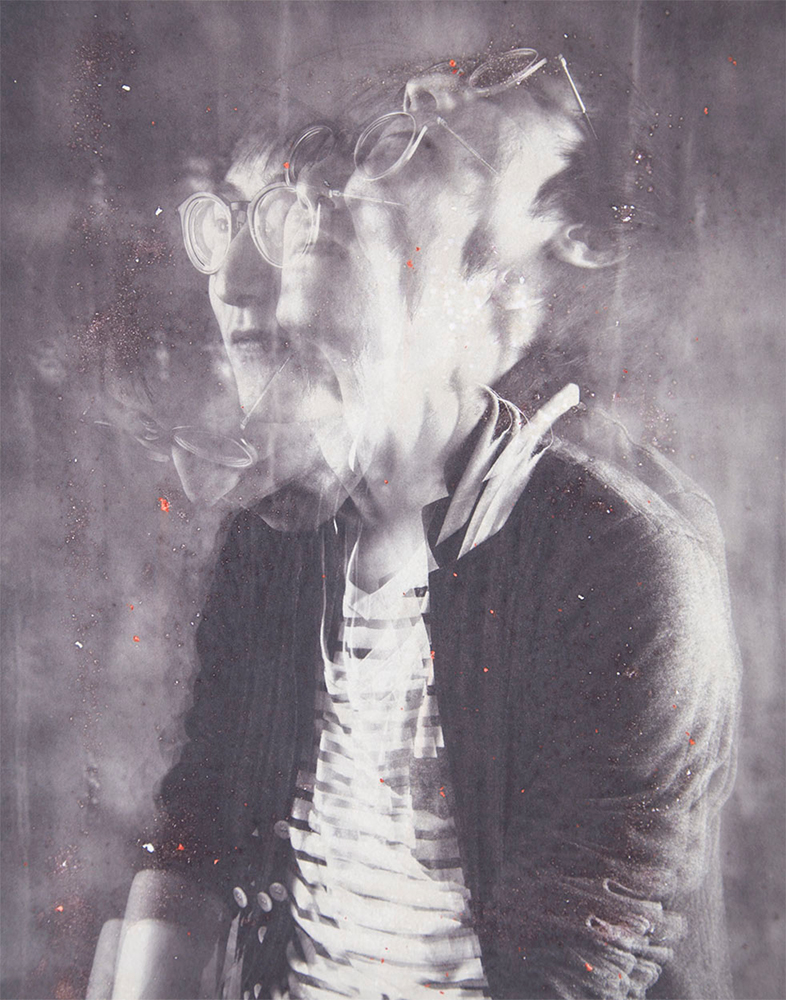

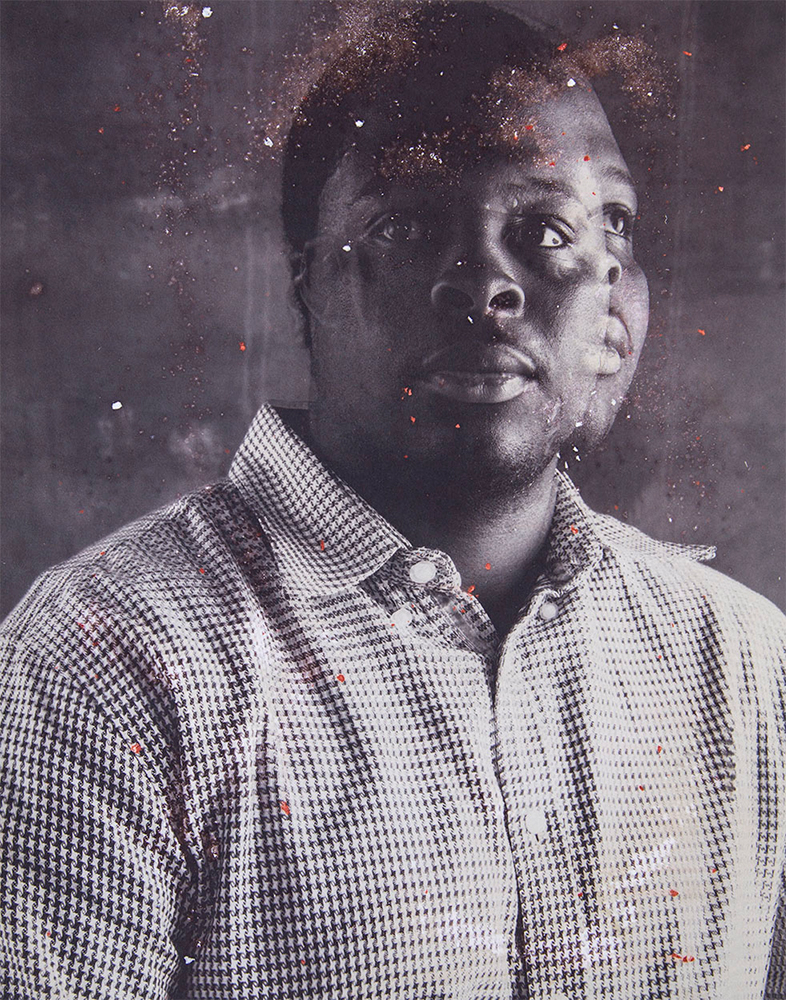

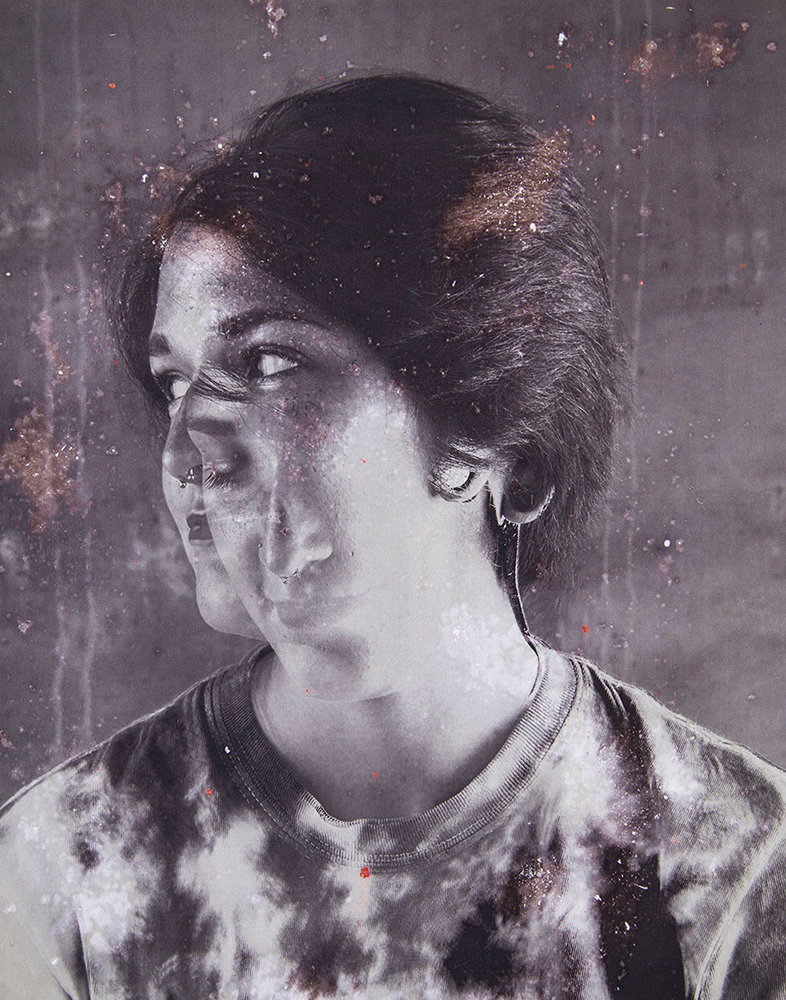

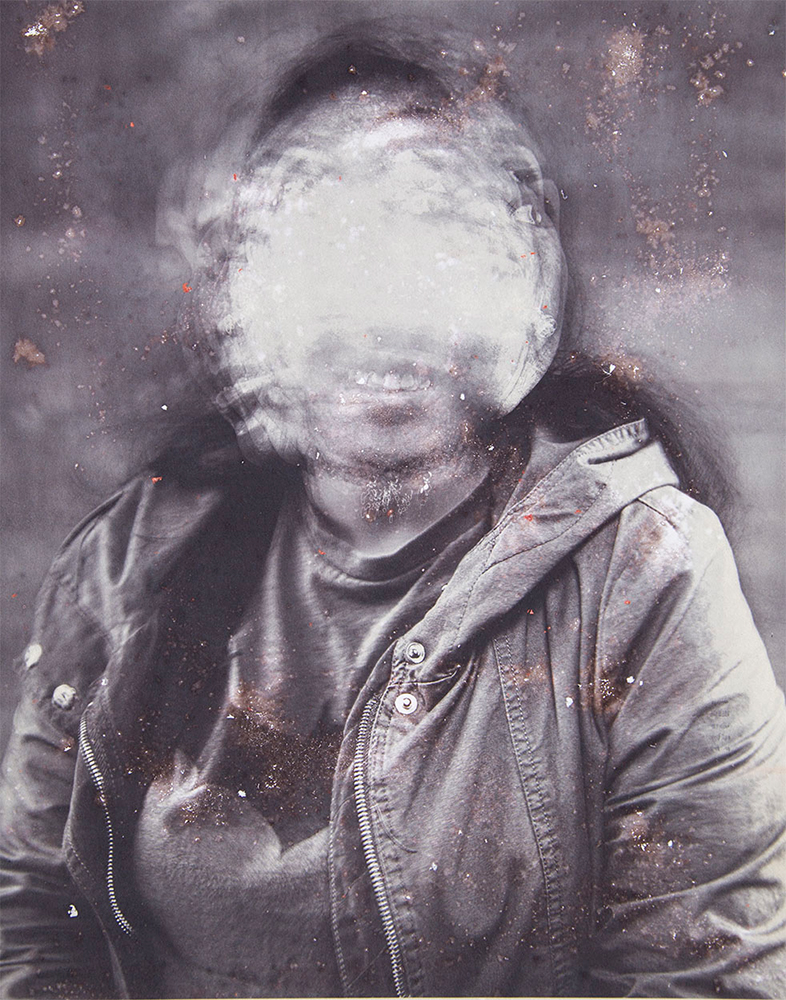

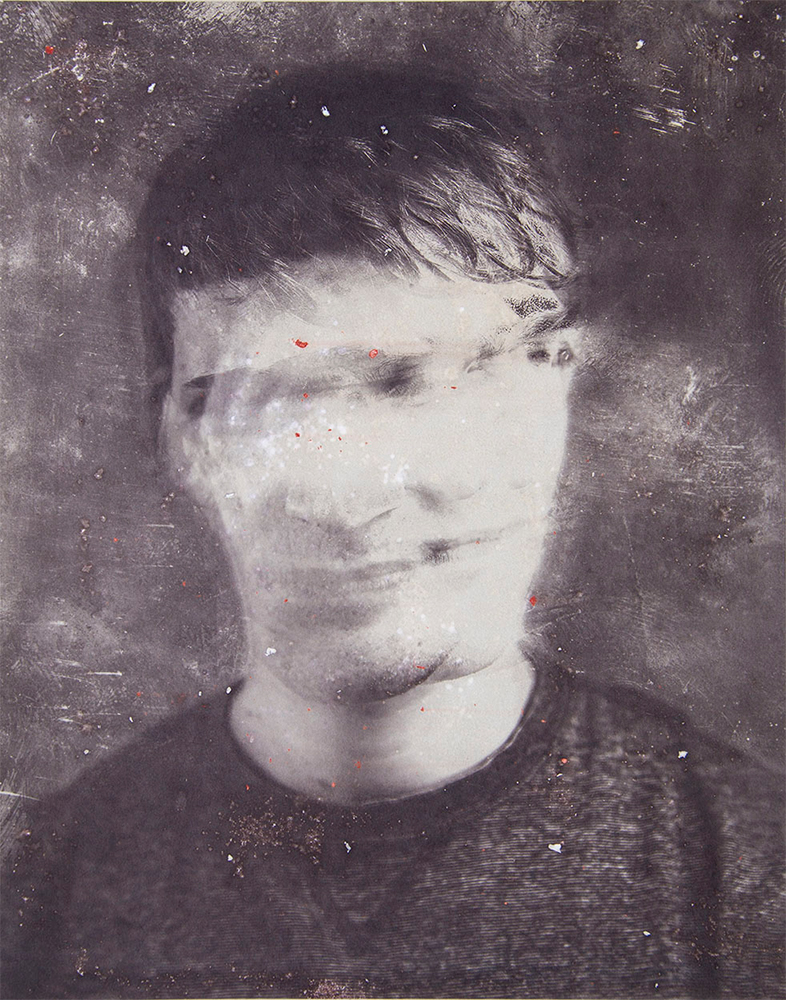

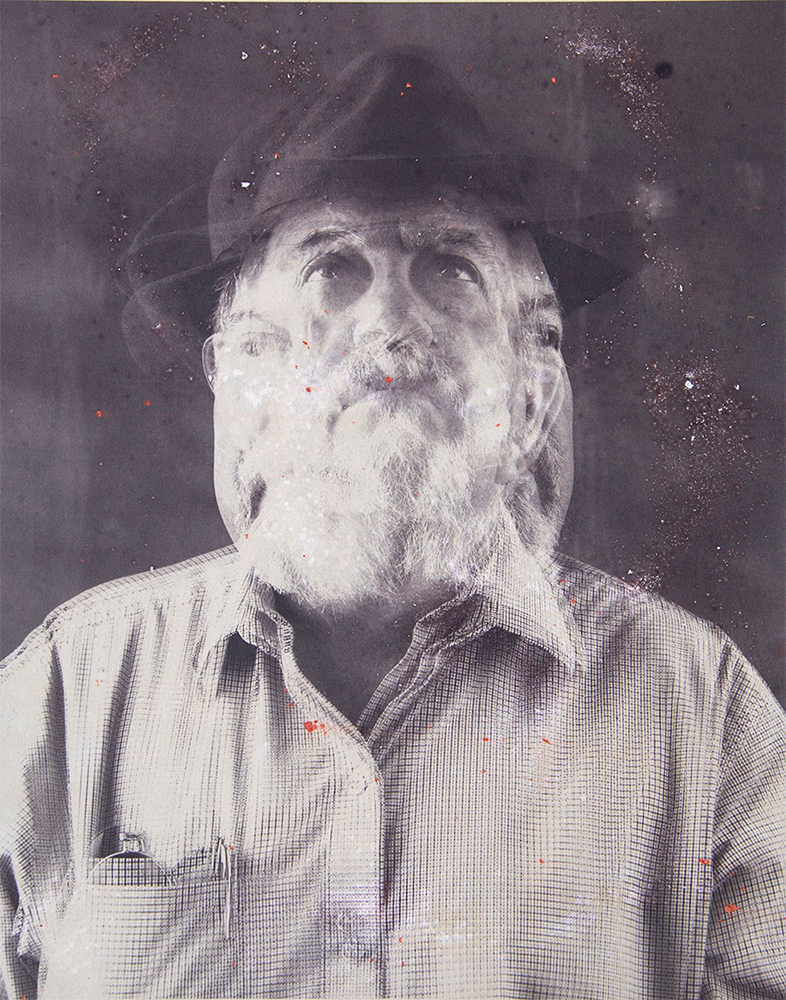

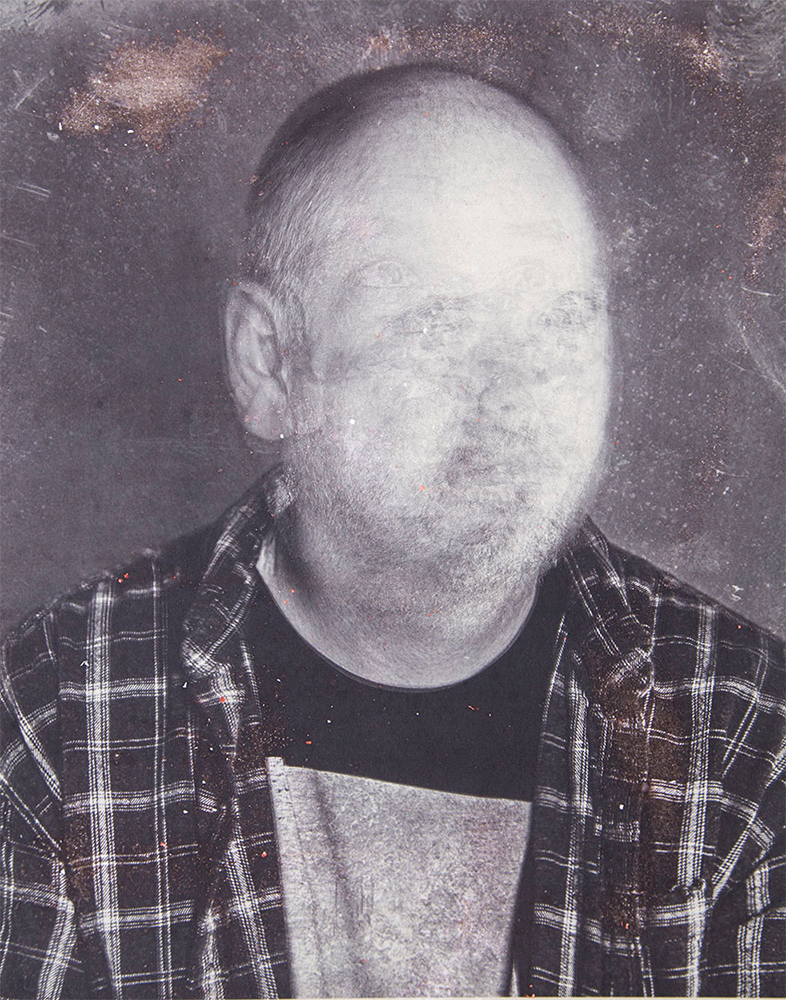

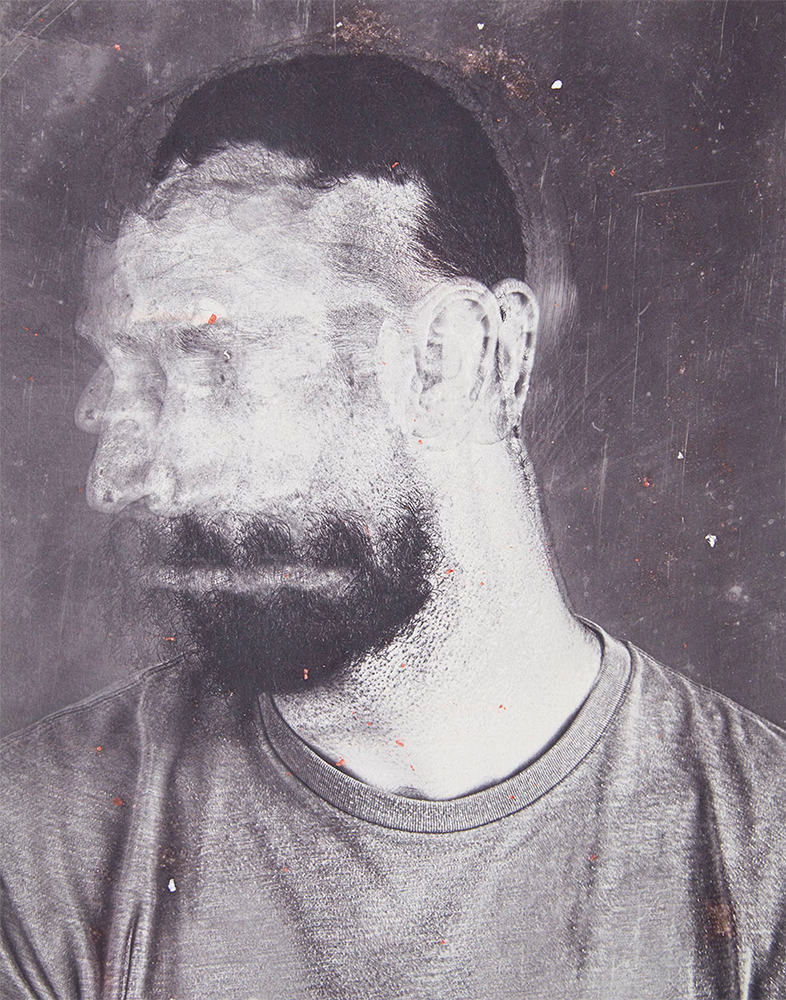

I met Brian James Culbertson my first year of grad school at East Carolina University. He, Addison Brown and I were the three who were typically in the alternative process room at the school until 4 am most nights. In his second year Brian told me about an idea he had for his thesis project. His idea was to add medication to the photographic chemistry. He chose to use the salt printing process, which is a process that is difficult enough without altering the silver nitrate. I graduated a year before Brian’s exhibition, but I saw many of his experiments with the chemistry in our last year together. Many of the early prints looked like a salt print that had been put in a tray of bleach and pulled early, before the print completely faded away. It was easy to see why this result was frustrating. To learn more about his process, Brian went to a salt printing workshop with Mark Osterman. When I graduated the project still seemed unresolved, but when I returned to see the graduate exhibition in 2018 the images had a wide tonal range and were surreal portraits, some with capsules from the drugs melting on the print.

It was fun to be around Brian after he put his work out in the world because people would offer him their medication to use in his prints. I specifically remember going with Brian and Addison to the Photostock festival, where someone gave Brian drugs for a print. We had to drive from Michigan to North Carolina with a prescription that belonged to none of us.

Originally from Chesapeake, Virginia, photographer Brian James Culbertson currently lives in Greenville, North Carolina, where he is an instructor of art at East Carolina University. Brian has exhibited work internationally participating in exhibitions across the United States, Canada, China, and the United Arab Emirates. His work has been featured in publications such as The Hand Magazine, Don’t Take Pictures, Light Leaked, and Fraction Magazine. Brian creates images that investigate photography’s influence on cultural and social values. His most recent research and body of work Adverse is focused on the prevalence of prescription medications in contemporary treatment of mental illness and, photography’s role in the representation of those living with mental illness.

Follow Brian James Culbertson on Instagram: @brian_james_culbertson

Adverse

I use my photographs to raise questions about the depersonalization in modern medicine, where prescription drugs are given out to individuals based on symptoms, regardless of differences in their physical or chemical makeup. Adverse uses both the process and the end result to highlight the danger of this one-size-fits-all approach. I create multi-layered portraits which are printed using the salt print process with prescription medication incorporated into the salt solution. The incorporation of medications used to alter the chemistry of the mind into the salted print process yields unpredictable results with each print – just as it does with our own bodies.

Greg Banks: Talk about your transition from skateboarding to music and finally to photography?

Brian Culbertson: My interest in skateboard culture ultimately led me to underground music and photography. In the mid 80’s the main source of skateboard culture available for consumption were magazines like Thrasher and Transworld. I was completely obsessed with the images of skaters in action that filled the pages.

As the media covering skateboard culture expanded into film/video I was introduced to underground music. This new interest in punk/indie music only led to more magazines. I found the grainy black and white images in Maximum Rock’n’roll magazine fascinating. Much like J. Grant Britain’s images in Transworld, the photographs that filled the pages of Maximum Rock’n’roll seemed to capture the subjects in such a peaceful way as they soared through the frame.

My friends and I would photograph each other skateboard with disposable 110 cameras with mostly disappointing results because we didn’t understand how to fill a frame properly. In my teens when I started to attend local concerts, I typically had a 35mm camera or a Hi8 Camcorder in hand. When I started to travel with my own bands, I would always have a camera with me to document the places we would travel to, but I still didn’t really know what I was doing with a camera beyond the few things I was shown along the way.

Once I decided to attend college, I knew I wanted to go for art, but I wasn’t completely sure what medium. I enrolled in a black and white photography course my first semester and I have never looked back.

GB: How did personal events lead to you making the series “Adverse”?

BC: My initial interest in making images that discuss prescription medications started in the summer of 2015. There were an alarming number of mass shootings that summer and with each incident the conversion quickly became about the shooters mental state and what medications they were on or perhaps not taking that they should have been. This felt like more of a way to push the conversation away from the larger problems of guns than a legitimate concern for anyone’s mental well-being.

At the same time, several people close to me were seeking treatment for anxiety and depression. Most of them felt that their doctors would write prescriptions for medications and if they had a negative reaction, they would simply try the next drug on the list until something works. While most had mostly manageable side effects, some experienced more severe side effects that were far worse than the symptoms they claimed to treat.

With friends sharing their experiences and news outlets suggesting that medications could possibly drive someone to commit such unthinkable acts, I certainly had a negative opinion of psychotropic drugs and their place in the treatment of mental illness.

GB: Almost immediately there was a relationship between what the medication was doing to the salt prints and the effects of the drugs on human beings. Talk about this and why you weren’t happy with that as a direction for your images?

BC: I certainly found the visible reaction between psychotropic medications and photo chemistry fascinating. There was an interesting parallel between the way people spoke of feeling “dull down” by these medications and the dullness of the prints I was making compared to a standard salt print but there was a lack of permanence that came with my experiments that I was not happy with at all. Even my most recent images shift over time but they do not entirely disappear like the first images did. While my images take on a bit a graphic quality through layering they still have at least hints of their original photographic qualities.

GB: Once you decided about the process, how did you decide on the imagery to go with the process?

CB: The initial images were very stereotypical portrayals of mental illness that I made without doing any real research into the history of images that portray mental illness in some capacity. They showed my subjects with their hands covering their faces, sitting alone in dark spaces, or showing some overly performative emotion. Once I started to research the history of this type of images, I realized that my images were only supporting this stereotypical view of mental illness and certainly not offering another perspective. The final images were inspired by a side effect that almost all the medications I work with shared as well as my own experiences with medications.

GB: Why did you decide to use the side effects for the titles of each piece? And was there something in each image that led to the title?

CB: From the start of this body of work I was drawn to the idea that these medications could come with such awful side effects. Side effects that sound far worse than what they were reported to help with. As I would get a new medication to work with, I would research all of the illnesses it was reported to help with and all the possible side effects of the drug.

Some of the titles were side effects the subject of that image reported to experience, while others were named after the side effects that I found most interesting/terrifying.

GB: What did you learn from your research about modern prescription medication?

CB: I was surprised to learn that so many medications prescribed today are used for so many different illnesses. It still puzzles me that a medication could be used for both anxiety and depression when they are very different illnesses. However, through conversations with those close to me and the subjects of my images, I realize how reactionary my initial feelings about prescription medications were and that while some people do struggle to find the right combination for their body, there are countless people that have experienced positive results and their medications allow them to manage their illnesses and still function throughout the day.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026

-

Carolina Baldomá: An Elemental PracticeJanuary 5th, 2026