Amber Zora: Cold Coast

I was lucky to meet Amber Zora this past summer in Aberdeen, South Dakota at the opening of the Midwest Nice Art exhibition. Meeting other artists in South Dakota is always a peculiar experience, but especially when they focus on the same discipline as you: to reminisce about similar upbringings in rural southeast South Dakota, see similar visual aesthetics in our practices, and talk about all of the fun Midwest cliches, like our freezing winters. Amber’s series Cold Coast is particularly relevant not only for us upper-Midwesterners in this season but politically and socially as well. Cold Coast is a personal reflection of Amber’s military time and an environmental and political study of the region affected by the Cold War. The formal images explore the ways the military injects itself into everyday life.

Follow Amber on Instagram: @amber.zora

Amber Zora is an interdisciplinary artist and curator based in Rapid City, South Dakota. She holds a bachelor degree in Studio Art from the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and an MFA in Photography and Integrated Media from Ohio University. Zora was in the US Army for eight years and was deployed as an ammunition specialist. Her work looks at the trauma of war, the military’s impact on the environment and rural America’s dependence on the military economy. Zora has exhibited her work in local and national galleries including the San Francisco Arts Commission, Chicago Cultural Center and the National Veterans Art Museum, among other spaces.

Cold Coast

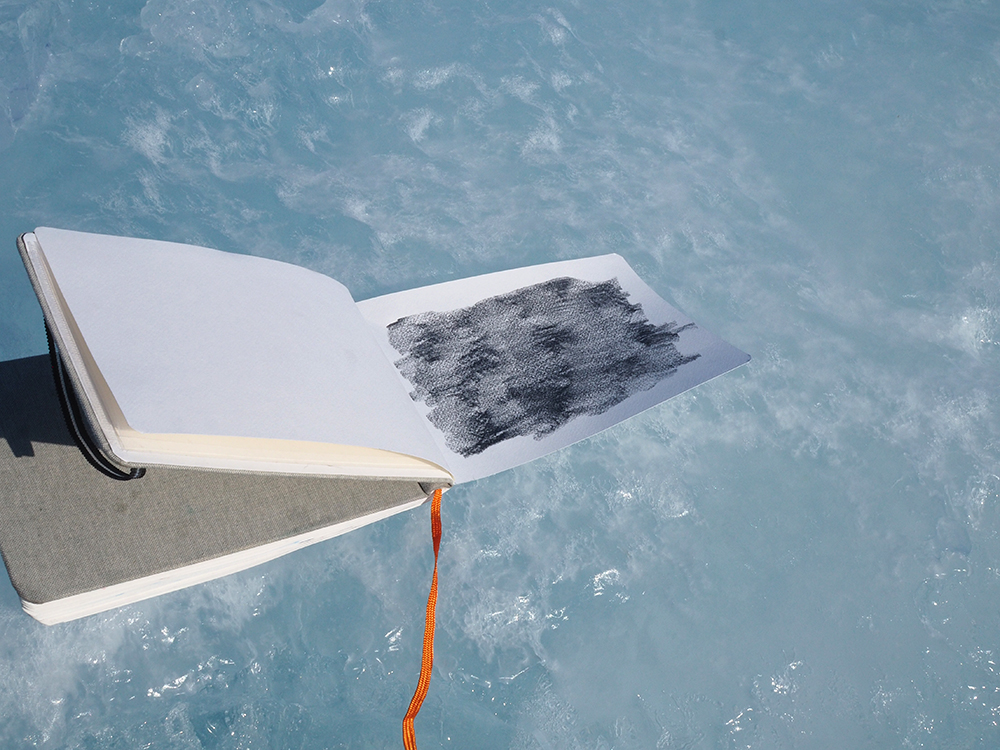

Cold Coast is an ongoing series about the Cold War, its relation to polar regions and climate change. These photos toggle between the 1947 – 1991 threat of a nuclear apocalypse and the current threat of a climate apocalypse. The Arctic has been and is a warning location for both of these manmade disasters. For instance, the Distant Early Warning Line, or DEW Line, was a series of radar stations across the arctic, from Alaska through Canada over Greenland to Iceland. It was set up to detect an invasion coming over the North Pole from the Soviet Union. Currently, we look to the Arctic for climate change predictions.

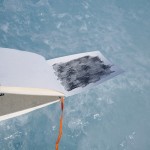

The images in this series are from the Svalbard archipelago located in the High Arctic and the Pyramid of North Dakota, which is a part of The Stanley R. Mickelsen Safeguard Complex. The complex was developed in the 1970s to detect and shoot down incoming Soviet Union intercontinental ballistic missiles. The pyramid has been described as a monument to the Cold War.

The Pyramid

I became interested in the Pyramid of North Dakota, when I learned that my great grandfather worked there and painted the inside of missile silos across North Dakota during the Cold War as a civilian contractor. Simultaneously, I met a small group of artists who were interested in the Pyramid as a catalysis for a series of monotypes and as a site for art. The more I learned about the Pyramid, the more interested I became in the military’s impact on the town and neighboring farms from an economic and environmental standpoint.

Back in the 70s, the neighboring town, Nekoma, was excited to have new industry that would bring in jobs and opportunity. The complex cost six billion dollars. From my perspective, the military came in, used up resources, and left. The facility was not open very long. Some people say it was only fully operational for a day, some say six months, others look at the building and development of facilities around the area as a part of a larger project. When the military packed out, they hired a contracting company to pull out any usable material. The generators were turned off and the silos filled with water. In 2012, the state health department issued a notice to the U.S. Army and Base Realignment and Closure Division that insisted the area must be cleansed of hazardous waste by removing about 420,000 gallons of groundwater that had seeped into the underground silos.

The Arctic

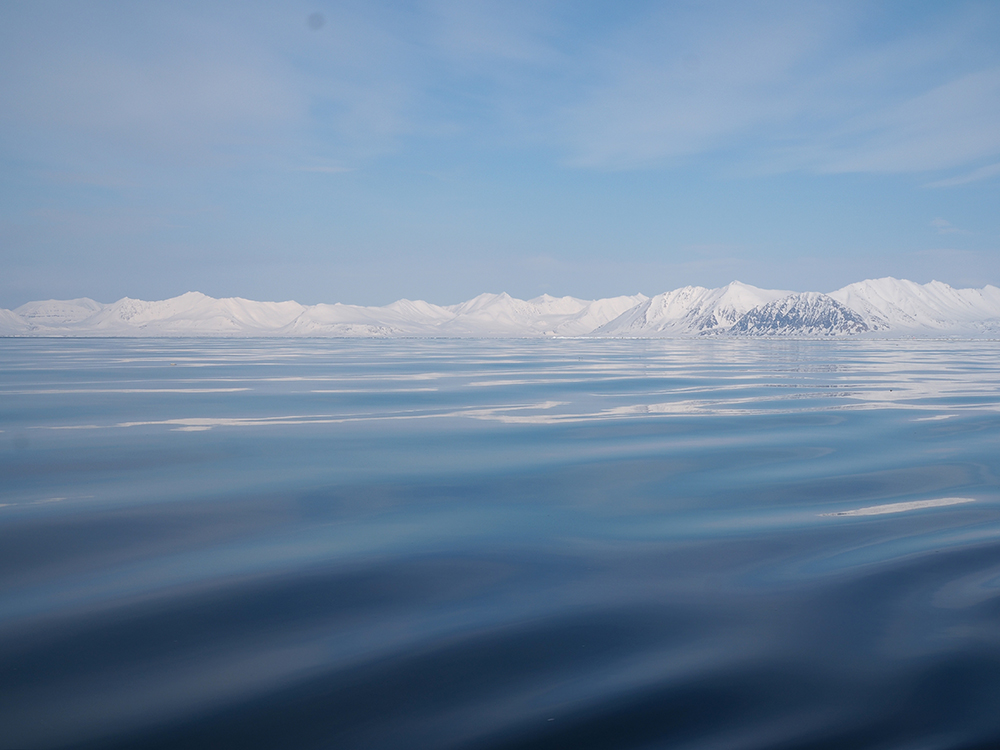

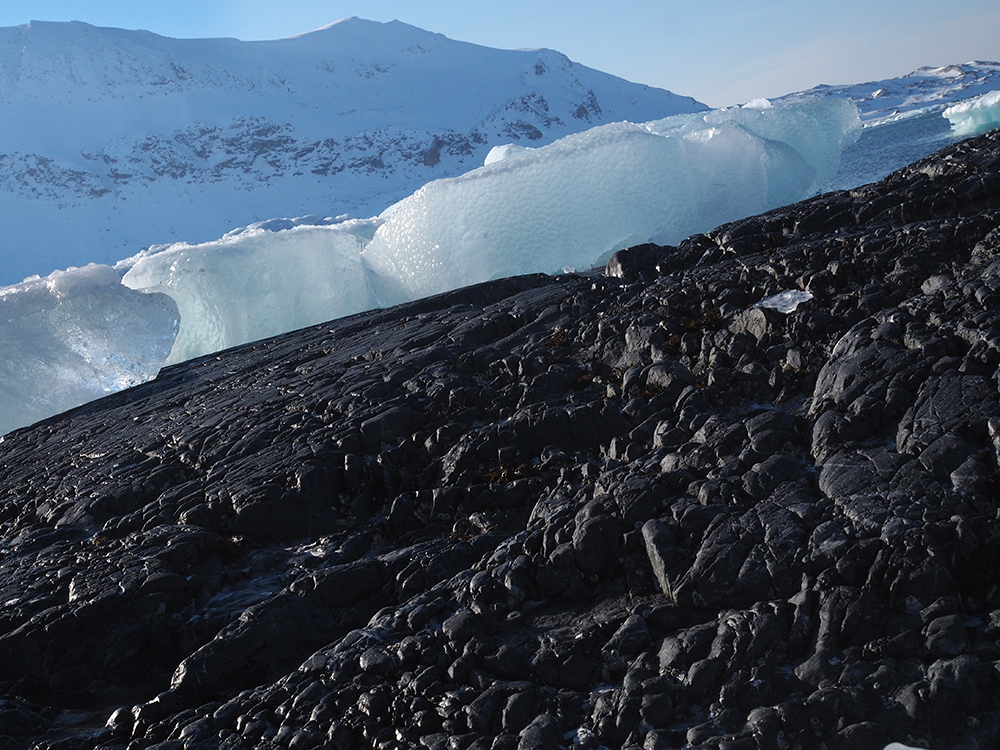

In April 2023, when I went to the Arctic, I thought about the Pyramid, the DEW Line and how in these secluded areas that we would not necessarily associate with the war are still touched by militarism. Svalbard is a demilitarized zone, but during WWII Nazis had weather stations there. This also led me to questions around demilitarized land: is land inherently militarized if it is not deemed demilitarized?

©Amber Zora, Signehamna, Svalbard. Relic from the weather station Knospe (1941-1942), then Nussbaum. Weather station built by German occupants during World War II.

In such a remote place, you can kind of imagine an apocalypse has already happened. While in front of glaciers, I would sway between the sadness of how humans have allowed this to happen to the planet, how the U.S. military is this huge contributor to climate change and how the happiest people I know are complacent to a lot of it. The United States Department of Defense is the single largest consumer of energy in the US, and the world’s single largest institutional consumer of petroleum.

In front of such old ice in a vast landscape with these thoughts and questions, I felt small. The Arctic is so brutal and beautiful, and at the same time very fragile. The brutality of the place, like most of nature, feels somewhat impersonal. Massive landscapes like that of the Dakotas and the Arctic can have a psychological effect. You can walk for miles and miles and seem to not move at all.

Learn more about Amber from her interview in Collateral Journal.

Epiphany Knedler is an interdisciplinary artist + educator exploring the ways we engage with history. Using Midwestern aesthetics, she creates images and installations exploring histories. She is based in Aberdeen, South Dakota serving as a Lecturer of Art and the co-curator for the art collective MidwestNice Art. Her work has been exhibited in the New York Times, Vermont Center for Photography, Lenscratch, Dek Unu Arts, and awarded through the Lucie Foundation, F-Stop Magazine, and Photolucida Critical Mass.

Follow Epiphany Knedler on Instagram: @epiphanysk

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Louise Amelie: What Does Migration Mean for those who Stay BehindMarch 12th, 2024

-

Janna Ireland: True Story IndexFebruary 17th, 2024

-

Krista Svalbonas: What Remains at the Marshall GalleryJanuary 26th, 2024

-

Amber Zora: Cold CoastDecember 28th, 2023

-

Naohiro Maeda: Where the Wild Things AreDecember 26th, 2023