Focus on Portraiture: Colin Roberson: Taxi Dance

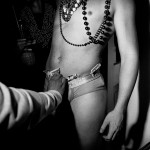

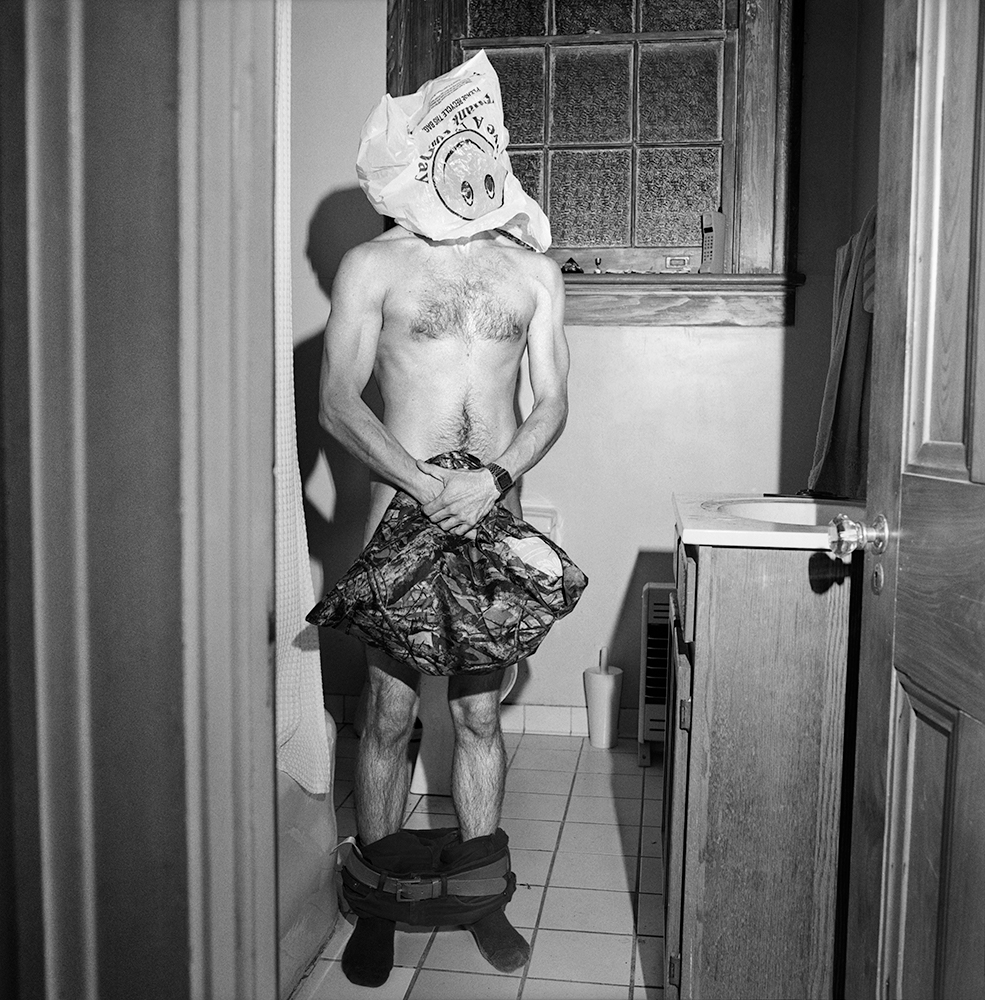

©Colin Roberson, Stuffing

Photographs of people are everywhere. As visual tools, they have many applications; faces are catalogued in identification databases. Bodies illustrate medical texts and pornographic magazines. Then there are those that seek to do more than simply record the physical characteristics of the person in front of the camera. These are what we think of as portraits- images of ourselves and those around us that function not only as visual records, but visual memories.

While the word “portrait” didn’t enter the lexicon until the 16th century, the impulse to memorialize ourselves and others can be traced back to the beginning of human history itself. Cave drawings and handprints left by our earliest ancestors seem to suggest that the desire to leave a record of one’s existence is an innate human instinct. It’s not surprising, then, that portraiture has been one of the most popular uses of photography since its inception in the 19th century.

Generally speaking, these early portraits were made in commercial portrait studios and follow a familiar format: the subject stands or sits in front of a nondescript background, their expressionless gazed fixed directly at the camera. This formulaic approach was one of necessity, not choice; the long exposure times required by early photographic emulsions limited subjects to poses they could hold for several minutes without moving. These early photographs were very expensive, and most people only had one portrait made of themselves in their lifetime- a single visual record of their existence.

Over the last 200 years, advances in technology and accessibility have made new kinds of pictures possible. Individual photographs no longer have to encapsulate entire lives. Instead, they are free to explore the intimate nuances of a singular moment in time. The portrait is no longer confined to the professional photographer’s studio; its territory is expansive. Every day, millions of people around the world are making portraits of each other- or themselves- in every setting imaginable. This liberated sense of authorship, access, and technology makes room for greater aesthetic freedom. Today, the “portrait” can be interpreted and executed in many different ways. This week, we’ll share the work of six contemporary photographers utilizing portraiture in their creative practice.

Artist Colin Roberson photographs through a lens he refers to as a participant-observer. Seeking to better understand the economy of desire, the images in Taxi Dance are visual notes from his self-reflexive investigation of the sex industry explored from the inside out.

©Colin Roberson, Jonas in My Bed

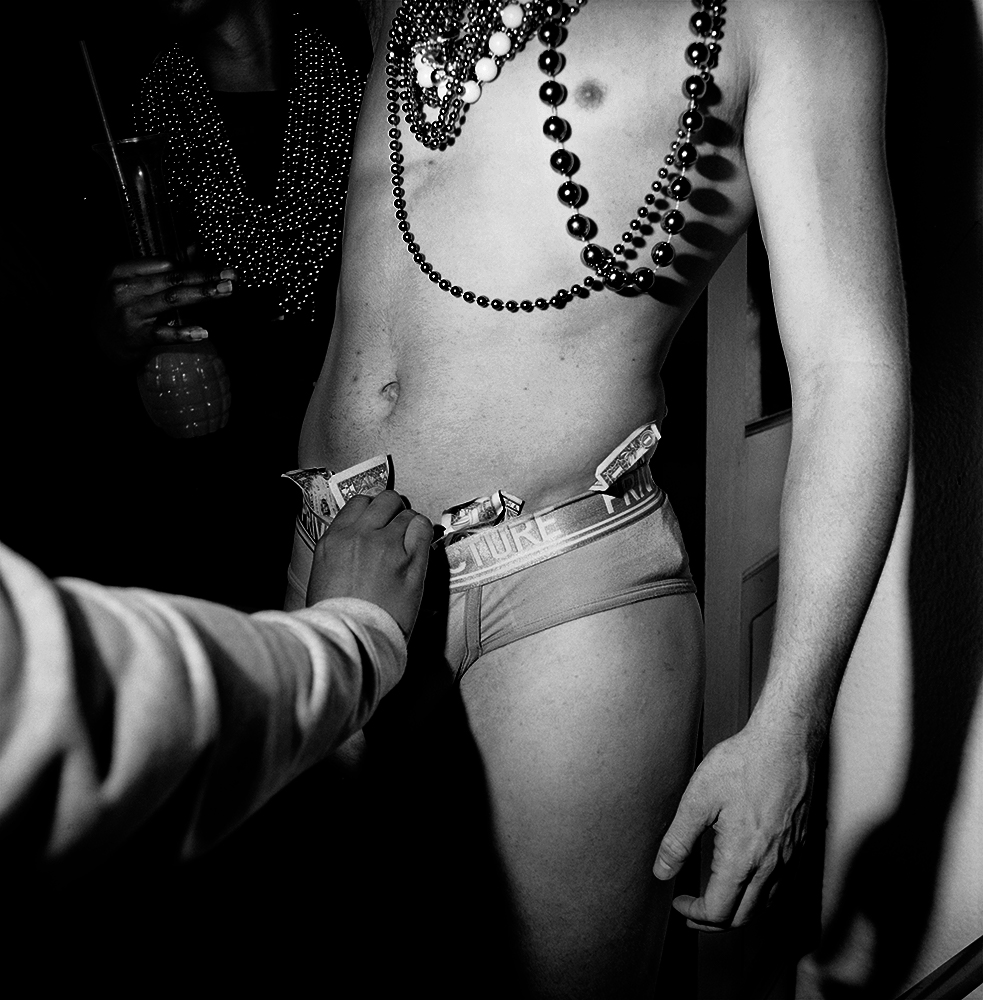

©Colin Roberson, Anonymous Locker Room

Taxi Dance

I hadn’t anticipated my first trick’s proposition. As the lights came up and the music died, he eagerly asked what it would cost to take me home. I laughed, then threw out the price of my monthly rent. After he agreed, I ran to the locker room to find out how much I should have asked. Someone said $1,000. A boy from St. Louis told me not to do it at all. Said once I’d made that much money, that quickly, dancing for $1’s would never seem enough. He said it was a door I couldn’t close from inside. I slept Uptown that night and made $400 cuddling. He wanted more, but neither he nor I could get him there.

“In the old romance of the artist, any person who has the temerity to spend a season in hell risks not getting out alive or coming back psychically damaged . . . there is a large difference between the activity of a photographer, which is always willed, and the activity of a writer, which may not be. One has the right to, may feel compelled to, give voice to one’s own pain—which is, in any case, one’s own property. One volunteers to seek out the pain of others.” – Susan Sontag, On Photography

I was challenged to pinpoint the redemption in this work by a guy who felt it bleak. Luckily redemption means both the act of making something better or more acceptable, as well as the act of exchanging something for money, an award, etc.

When I asked my dad if I should entertain a man who was proffering big city gallery connections, my father echoed that other dancer’s warning. He assured me the right person will “see you” the way most everyone else cannot. To him, anything less than this sort of honest acceptance isn’t worth the time. He lives with his mother. – Colin Roberson

©Colin Roberson, 4 AM

©Colin Roberson, Self-Portrait with Him

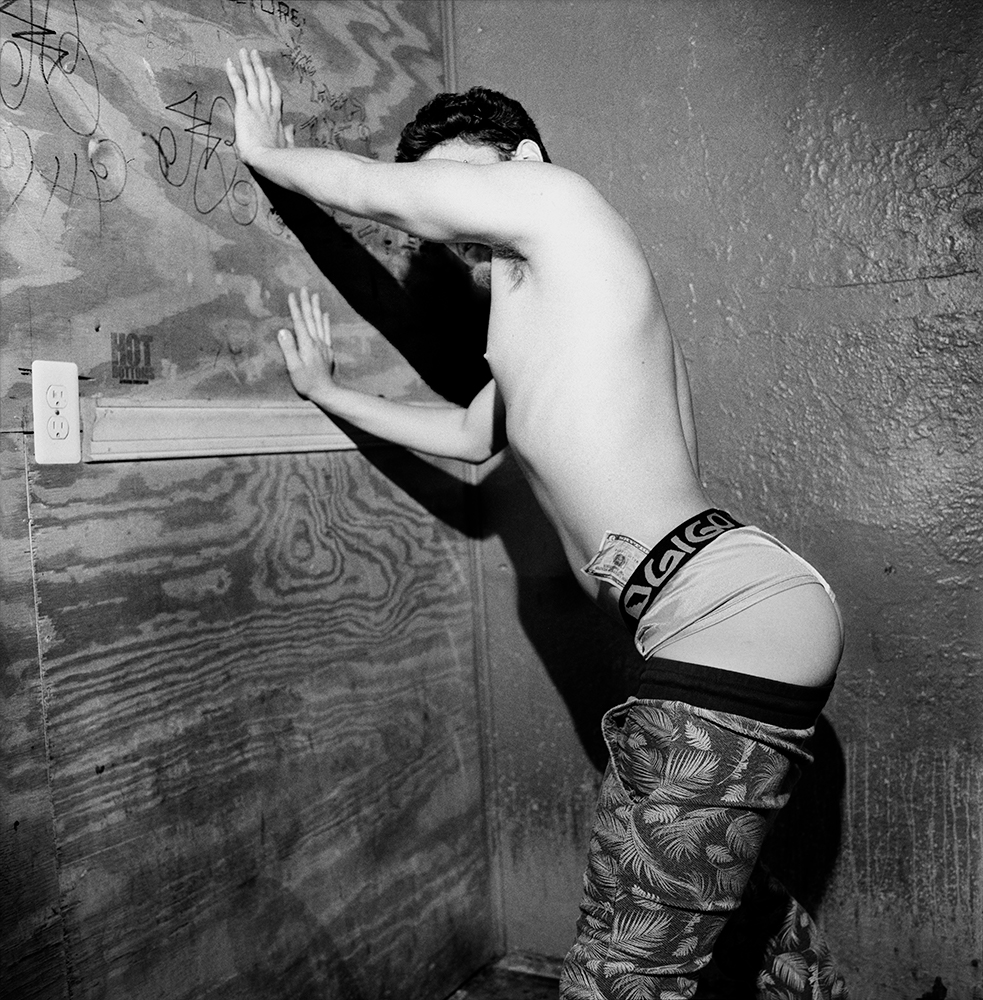

©Colin Roberson, Locker Room, 3 Graces

©Colin Roberson, Bella and Diamond

©Colin Roberson, Anonymous Friend

©Colin Roberson, Josh and Katt

©Colin Roberson, Jessica at Dawn

©Colin Roberson, Around Midnight on Rampart Near Tolouse

©Colin Roberson, Will, Mexico City

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026