Bill Adams

I met Bill Adams at the recent SPE conference, and was very disappointed to miss his lecture (which I heard was A-mazing). Bill approaches photography from a unique point of view – with a freedom, creative wackness, and sense of humor this community is so sorely lacking. I am sharing a few paragraphs from his must-read Wickipedia page:

What I DO know about Bill Adams is that he was born in Walnut Creek, California, in 1964, and grew up in Santa Cruz. He received a BA in Politics from Princeton University, and an MA and MFA in Photography from The University of New Mexico. He was selected a fellow of the American Photography Institute National Graduate Seminar in 1992. His work has been reproduced in Exploring Color Photography (Editions 2-5) as well as Light and Lens: Photography in the Digital Age. He was recently featured in the journals Exposure and Copper Nickel. He teaches photography at The University of Colorado Denver. Bill lives in Lakewood, Colorado, with his wife, Carol Golemboski, a Center Project Competition winner, and their two children. I can only imagine their creative household.

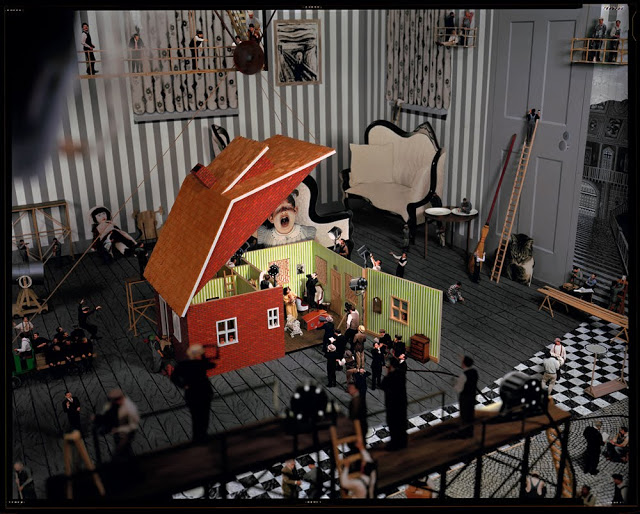

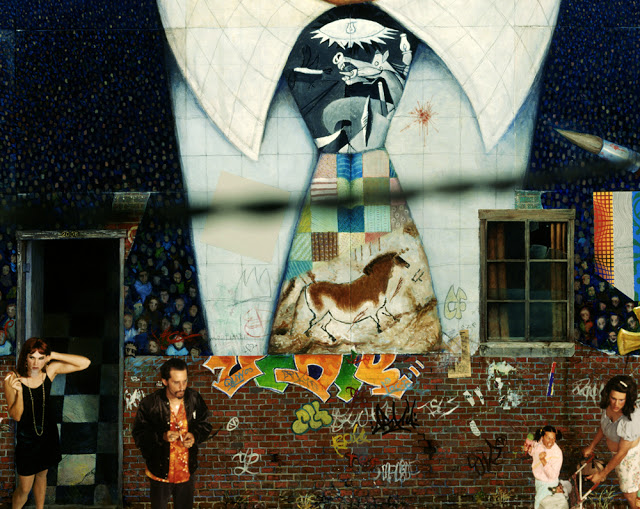

I make large, humorous color photographs of elaborately staged scenes in which I play numerous different characters. I typically work on these complex sets for several years, and make successive versions of the same image.

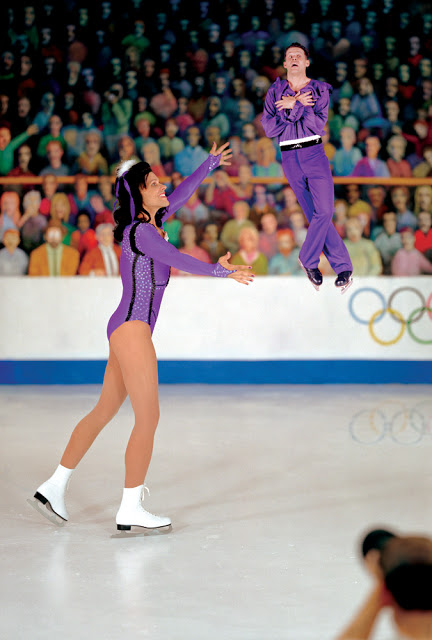

Most of the characters are actually photographs mounted on cardboard. In some images, like Pairs Throw Axel, there is one real person surrounded by life-sized photographs.

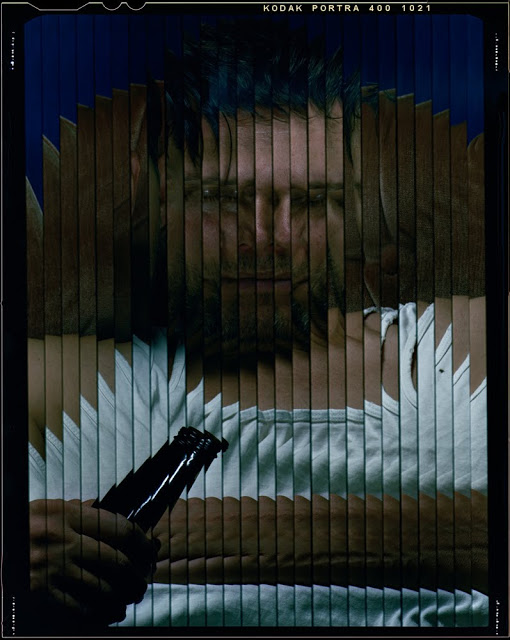

The figures in Dollhouse are about eight inches tall, those in Dead Eye about two feet. The final images are photographed with a 4×5” or 8×10” view camera, enlarged optically, and developed in a chromogenic processor.

While an initial inspection reveals that all of the characters are the same person, suggesting a digital composite, further examination indicates a straight photograph of a complex staged scene. There are often clues to the illusions, such as reflections of the back of cut-out figures lying around the set. The relationships of the different characters contrast with a single artist enacting a drama for his own pleasure or glorification—or for a self-conscious work of art.

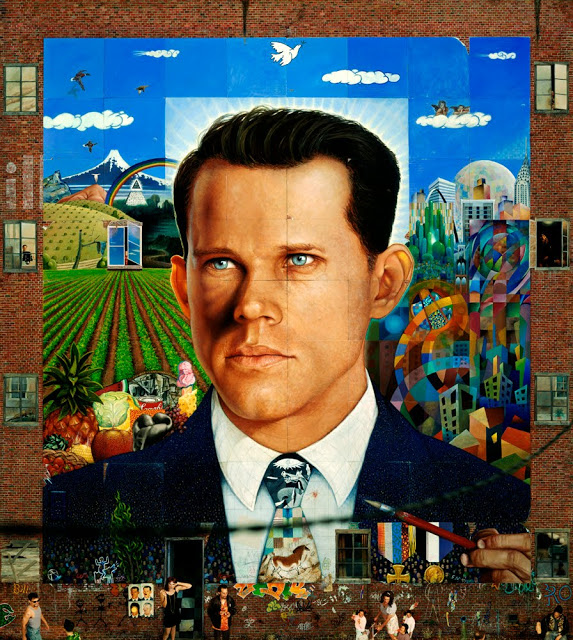

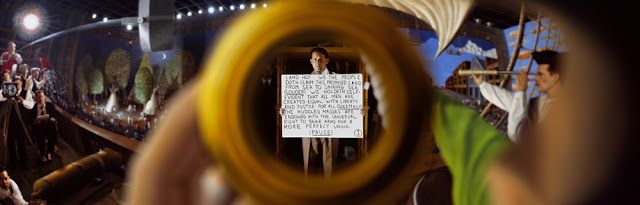

Many of the scenes depict film sets, premieres, and other spectacles. The shifting identifications and points of view revolve around issues of voyeurism, perspective, and power. Some of these illusory characters are staging their own simulations, which mimic my own. In Dead Eye, the film’s killer’s point-of-view shot mirrors the point of view of the victim through whose “dead” eye we are looking.

Pieces such as Universal Picture and Point and Shoot lay claim to being completely transparent, extending the notion that the lens pictures what the eye sees. Since it can only depict what one eye sees, these perspectives represent a single eye looking through a spyglass or sniper sight.

Some images simultaneously observe a parallel attempt to create a visual model, whose shortcomings undermine the premise of optical realism. In Trompe L’Oeil, the Victorian painter’s own blurry nose is a reminder that what we think we see is very different from what is present in our visual field. The image further suggests that a visual model is a function of an ideological perspective. Conceptions of realism are socially constructed, and inevitably reflect prevailing power relations. The subservient maid, sumptuous decor, and Romantic painting style express upper-class Victorian values, even as the painter attempts to objectively record optical experience.

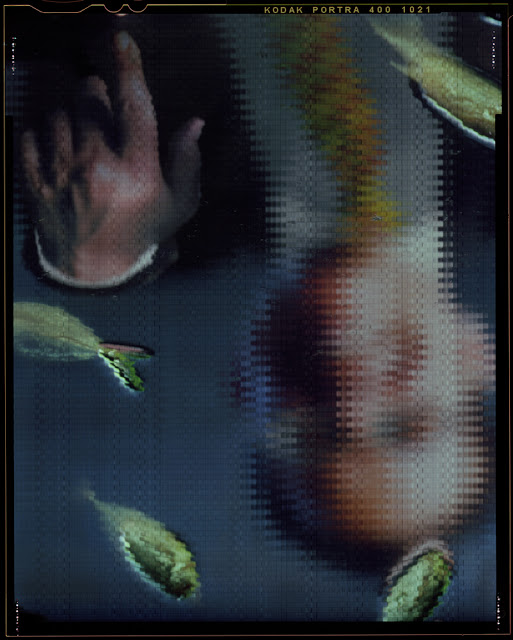

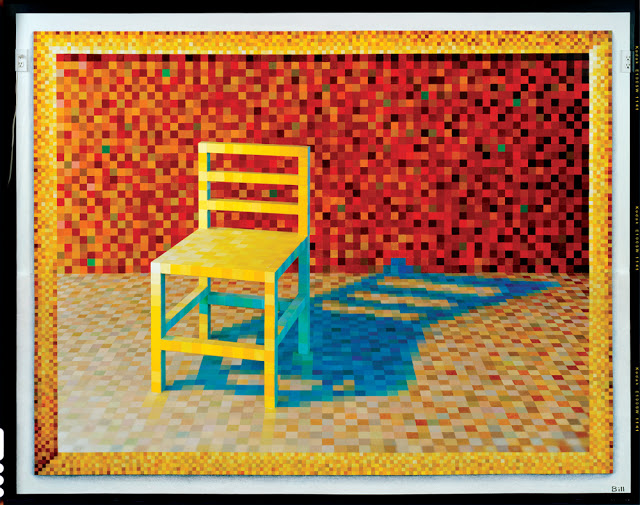

Recent photographs contain apparently digitized areas, which are actually painted floors, walls, tables, and suspended objects. In Bachelor Party, the thousands of squares are painted, while the stripper’s pixelated breast is a small board suspended between the camera and the figure. This simulated computer manipulation suggests that parts of the picture were not only photographed at different times, but perhaps were never present at all.

This digital fig leaf creates a kind of voyeuristic censorship, although what it purports to hide, it in fact supplies—and what it creates might itself be “enhanced.” Yet this elaborate artifice is itself a kind of authentic fraudulence, for it is not digital but a physical object, and it is not an augmented woman but a real man.

This digital fig leaf creates a kind of voyeuristic censorship, although what it purports to hide, it in fact supplies—and what it creates might itself be “enhanced.” Yet this elaborate artifice is itself a kind of authentic fraudulence, for it is not digital but a physical object, and it is not an augmented woman but a real man.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Salua Ares: Absense as FormNovember 29th, 2025

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025

-

KELIY ANDERSON-STALEY: Wilderness No longer at the Edge of ThingsNovember 19th, 2025

-

Jackie Mulder: Thought TrailsNovember 18th, 2025