SW Regional SPE: Brenda Biondo

Sharing photographers that I met at the SW Regional SPE Conference hosted by the Center of Fine Art Photography in Fort Collins, Colorado….

When I met Brenda Biondo and spent time with her terrific project, Once Upon a Playground, I realized that it had so much potential–as a teaching tool, as a museum exhibition, and as a book. As a teaching tool, it was a great reflection of how a project forms, from a few photographs and ideas, growing into significant research of a subject adding additional layers of insight and thought. As Brenda states, she discovered that no institution is documenting objects of play, and her project may one day, be an important historical record. Her museum options range from Children’s Museums, The Museum of Play, the Smithsonian, and a host of other options. Finally, the book dummy that she shared in Colorado is a thorough and fascinating look at the history of playgrounds. Publishers, where are you?

Brenda received B.A. degree in communication arts from James Madison University in Virginia. After working in corporate communications in Manhattan and Washington, DC for a decade, she left the corporate world to focus on freelance writing. As a writer, she had her work published in The Washington Post, The Denver Post, The Christian Science Monitor, USA Weekend magazine and many other publications. In 2004, she decided to discontinue writing in order to concentrate on fine art photography. Her work has appeared in group and solo shows throughout the country, including exhibits at the Center for Fine Art Photography in Fort Collins, CO; the Hubbard Museum for the American West in Ruidoso Downs, NM; the Dairy Center for the Arts in Boulder, CO; and the Torpedo Factory in Alexandria, VA. A native New Yorker, Brenda now lives in a small Colorado town at the base of Pikes Peak with her husband and two children.

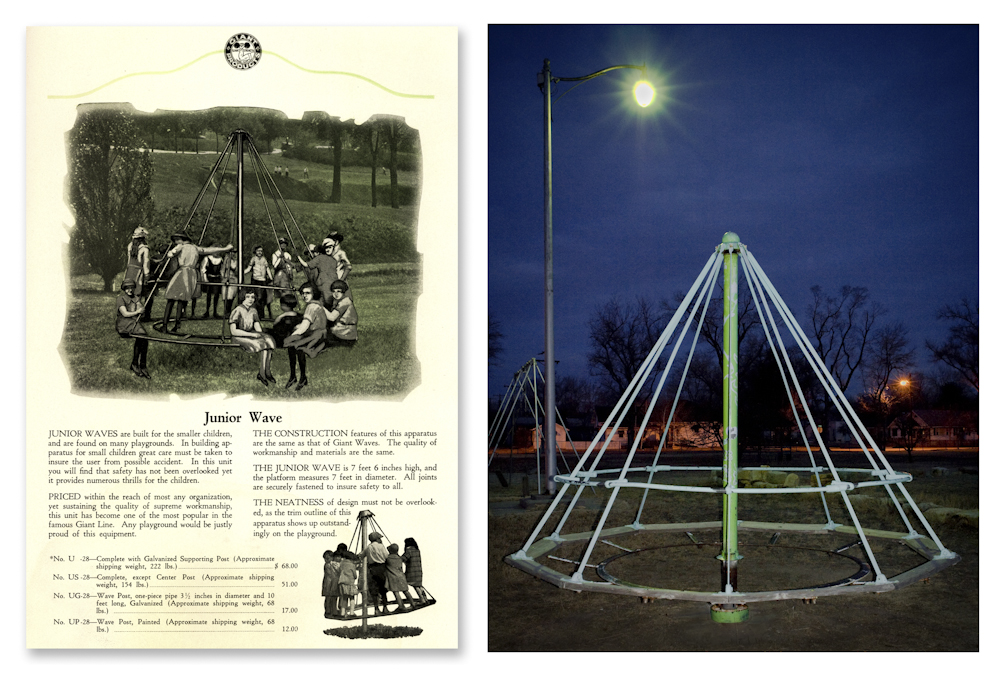

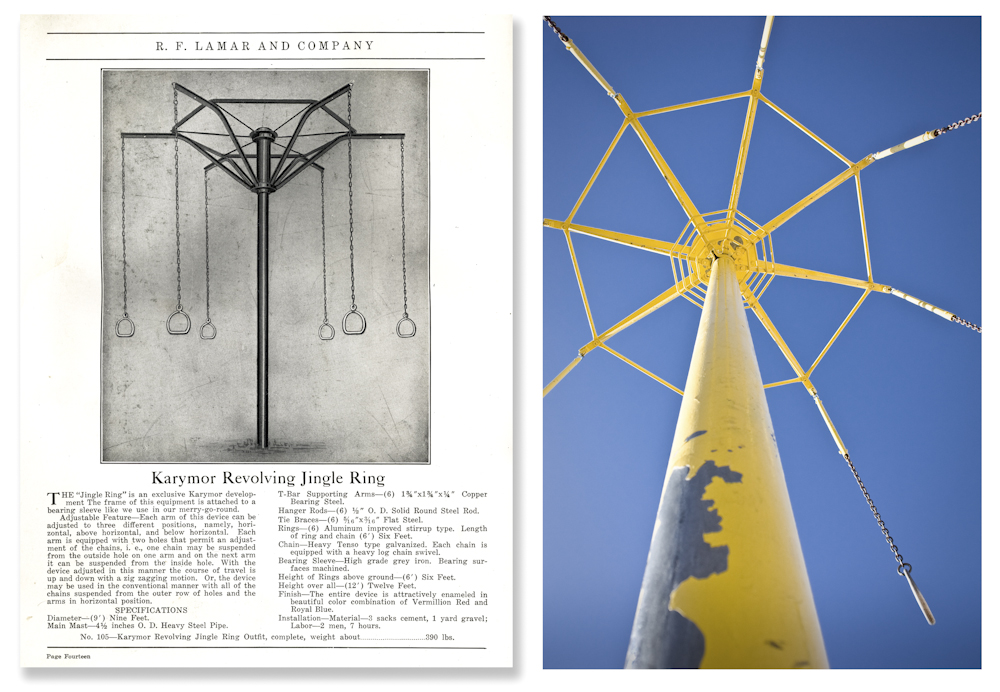

This was the first project I started after turning 40 and having my first kid. Even though I had been taking photographs for more than two decades, I had never pursued it seriously until then. As I was thinking about subjects I could shoot with a baby in tow, I began noticing that the local parks I visited with my young daughter hardly ever had the type of equipment I had grown up with.

Unfortunately, it gets harder to find this equipment with each passing year. When schools and towns renovate their playgrounds, the old equipment is almost always hauled away to the scrap yard. As far as I can tell, no institution — hello, Smithsonian — is collecting and preserving this equipment. I can’t remember how I stumbled across the first playground catalog on eBay, but I began buying them whenever one came up for auction, not really sure what I would do with them but knowing they provided historical context for my photographs.

After several years, I had nearly two dozen catalogs, published from 1920 through 1975, along with a growing pile of historical playground postcards. I’ve recently combined the historical documents with my photographs and created a book on Blurb to show to potential publishers. All the elements of the book are viewable on my website, www.onceuponaplayground.com.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026