Some months ago, I met Jenn (JT) Blatty when she sat down at my reviewing table at PhotoNOLA. I always like to look at a photographer’s website before we meet and in doing so I read that she had been a soldier in Afghanistan and Iraq. The work that Jenn brought to the review reflected some terrific documentary work about the fishing industry, The Fish Town Project and another fine art series, Parallel, but I couldn’t escape the nagging feeling that Jenn had quite a personal story to tell. With my urging, she went back to her journals and her photographs–not taken as fine art, but simply to capture places and people.

The Fish Town Project: The Bottled Bayou and Al

from Parallel

After graduating from West Point, Jenn had two Tours of Duty, the first in Afghanistan and the second in Iraq. She served six years as an active duty Army Officer and her passion for photography grew from her desire to capture the culture and people of places she had visited. In addition to her photographic pursuits, Jenn is a FEMA Disaster Reservist photographer, in fact, Hurricane Sandy pushed this post back a number of months. She recently created a new body of work, Rockaway Recovery, from her time spent in Sandy’s aftermath.

This is a two-day post, and today we focus on her first tour. I appreciate the effort Jenn has taken to re-examine her past and share excerpts from her diaries, and of course appreciate her service to our country…

Jenn’s story:

I was 23-years old when the twin towers crumbled to the ground: Only a year out of West Point and a year in with the 92ndEngineer Combat Battalion. I was a Platoon Leader of 35 men in a construction unit, most of them far older than myself and very well seasoned in the Army.

In January 2002, I was strapped to the sidewall in the belly of a C-17 cargo plane, my stomach twisting at the thought of breaking a promise to call my Mother before boarding a flight into Kandahar, Afghanistan.

Looking back through my old deployment scrapbooks now, it’s hard not to be my own worst critic. Why didn’t I shoot that like this? Or why didn’t I bring a good camera? Or my favorite, couldn’t I have gotten a little closer?

And I laugh to myself when following up with those thoughts, thinking about what could have happened if I even used the word “shoot” so freely then, or answer my own question: No, I couldn’t have gotten closer. Remember the land mines?

My life was the Army then, and I wasn’t a photographer. I was simply taking pictures, or snapping shots of my life–I wanted to share a world that was so far removed from the one I left behind with my loved ones. I wanted them to see through my eyes: The people, the landscapes, even the small beauties that could easily be taken for granted.

But isn’t that what we all innately do as photographers? Isn’t that what defines us, before we develop our skills and invest in fancy equipment? On a second look through my old scrapbooks, I realize that maybe I was just as much of a photographer back then as I am now.

Snapshots Sent Home: Kandahar/Bagram, Afghanistan 2002

We were the first rotation into Afghanistan: There was no one at home for our families to ask, “what’s it like there?” and telephones weren’t exactly an option. So every now and then, I would enclose exposed disposable cameras and rolls of film with the letters I wrote to home.

Day 1, Kandahar, Afghanistan

Pure adrenaline: The sound of my heart pounding against my chest and the C-17 jet screaming through the air. As I sat there strapped into the seat on the side of the aircraft, watching the other soldiers loading their magazines with ammunition, it all finally became a reality. We were out of our element; our only expectations were manifested by fear and what we had seen on television.

No windows for a sight tip of our future home. The back door of the C-17 dropped open like the mouth of a monster, opening the gateway into the unknown. We walked out in a single file, loaded down with our gear and weapons slung across our backs. This was the true definition of “pitch black;” stars illuminating like a billion suns, no technology for miles. I dug into my rucksack for a pair of gloves. They said Afghanistan was harsh in the winter, but I wouldn’t believe it until the bitter cold wind nipped at my hands.

Members of 1st Platoon breaking at a future mission sight where we would build a fence to prevent future soldiers from walking on minefields. Kandahar, Afghanistan

Our living area, Kandahar, Afghanistan

1st Platoon unpacking and inventorying tools, Kandahar, Afghanistan

View through the empty building from across our living area, Kandahar, Afghanistan

1st Platoon completing construction of a temporary detainee facility for captured Taliban, Kandahar, Afghanistan

Outside of the local quarry used by our unit for construction fill, Kandahar, Afghanistan

The Afghan locals worked on the base, but we couldn’t help to feel a bit wary of them swinging their AK-47s around like toys. And we couldn’t prohibit them either, unless we wanted to rock the political boat with the local warlords. Junkyards of blown up Soviet aircrafts and shot up vehicles lined the roads. I felt as if I were walking through a war museum. Often we would find old Soviet Kevlars and bayonets buried in the rubble. The Taliban only weeks before our arrival had made their last stand here against the Northern Alliance, and now I was working out of a building that was no doubt a tomb shortly before.

Chinook supply delivery to Jalalabad, Afghanistan, bordering Pakistan.

First arrivals of U.S. troops to Kandahar are welcomed by the Northern Alliance and town leadership with a “feast.”

Bagram Air Base/Kabul, Afghanistan

One morning, my roommate brought it to my attention too perfectly: “I realized this morning, when I was walking across the street, that I didn’t notice the mountains anymore. I don’t want to be that way.”

I knew one day I’d look back on it all and remember only the good, and the good that came from the bad. Moments like my first night in theater, full of apprehension and confusion, sitting alone outside of my tent, and something drew my attention to the sky. At that exact moment I witnessed the most mysterious and bright shooting star I had ever seen, so unique in it’s own nature that I considered it to be some new discovery of life or science. I knew it was a sign, telling me no matter how ugly and cruel the world may seem, there’s always a beauty so powerful to make it all worth the suffering: Beauty like the snowcapped mountains surrounding us, or the wild flowers blossoming in the most ugly and awkward places. Or when the scorching sun went down in the evenings, and night after night, the weather was like that of the one perfect day when the summer and fall come to a compromise. Even beauties like the Afghan chanting and praying in the distance at night, and the wind would carry his voice in such a manner that we didn’t know if he was sitting right next to us, or 5 miles away.

Remains from Afghanistan’s wars.

Landmine. We were instructed only to walk on paved areas.

We’d wake up to tent shaking explosions echoing through the night. Go back to sleep, it’s just a flare; they’re checking the perimeter for enemies probing the line. Never mind that 300 Rocket Propelled Grenade threat that was predicted for tonight. Just fall asleep in your boots, flak jackets, and load-bearing equipment, and be ready to run for the trenches if you hear the air horn. I wrote letter after letter to home, ensuring I said everything I ever wanted to say, just in case.

Every once in a while, we would hear about an Afghan child, fellow soldier or international soldier setting off a mine and losing a limb or their life. It would take decades to remove even 50% of the unexploded ordinance from Afghanistan. Sometimes we’d ride with the contractors down to Kabul when supplies were hard to come by on post. The 3-foot interval piles of painted rocks used to mark the mines lining the sides of the road destroyed the beautiful scenery. And I mean they lined the sides of the road for miles; yet you’d see cattle herders and children leisurely running through the red danger signs as if they were going to pull them from the ground and fly them like kites.

Repairing the airfield in Bagram to allow landing of larger aircraft for future deploying soldiers.

Self-entertainment. 1st Sergeant Poulin, or “Top,” poses next to the mock McDonald’s sign on the Bagram Airfield.

The winding road from Bagram to Kabul where the countryside is rich with mountains, Poppy flowers and war wreckage.

Downtown Kabul

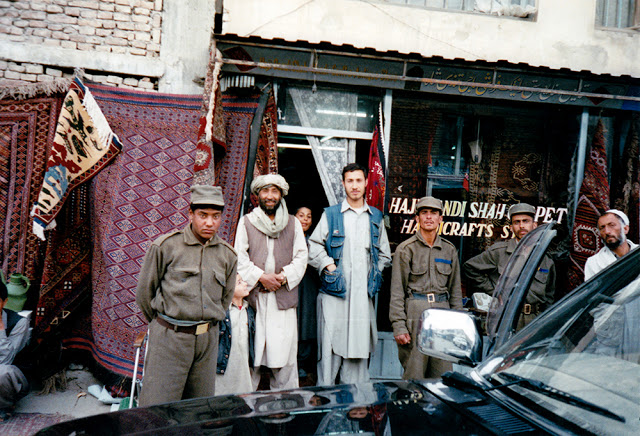

Chicken Street, Kabul

Chicken Street, Kabul

Chicken Street, Kabul

Chicken Street, Kabul

Chicken Street, Kabul

Myself with an Afghan girl on Chicken Street. When leaving base we were required to wear civilian clothes.

We didn’t sleep the actual night before our flight home. Instead we journeyed up to the flight line that evening, and waited for our plane to land and take us away at sunrise. I’ve never seen such a picture as I did of that C-17; nothing had ever looked so promising. This was all a dream. I never left in the first place. How did I deserve something such as this gift of going home?

Not hours before the plane flew over Savannah, my home, something strange happened. I didn’t know how to feel anymore. I didn’t know how I was supposed to feel. I wasn’t ecstatic, I wasn’t sad, I just was. And then I became afraid. I was afraid of the relationships I left behind. I was afraid of the customs, the cell phones, the routines people would expect me to fall back into. Because I was different, I was changed. For better or for worse, I didn’t know at that point. But the person on that plane was far different from the person who had left six months prior. And it terrified me so much that I couldn’t seize the prize we won for doing our time. But it would be all right. Everything would always be all right.