Ryota Kajita: The States Project: Alaska

Alaskan Guest Editor Ben Huff share the work of Ryota Kajita

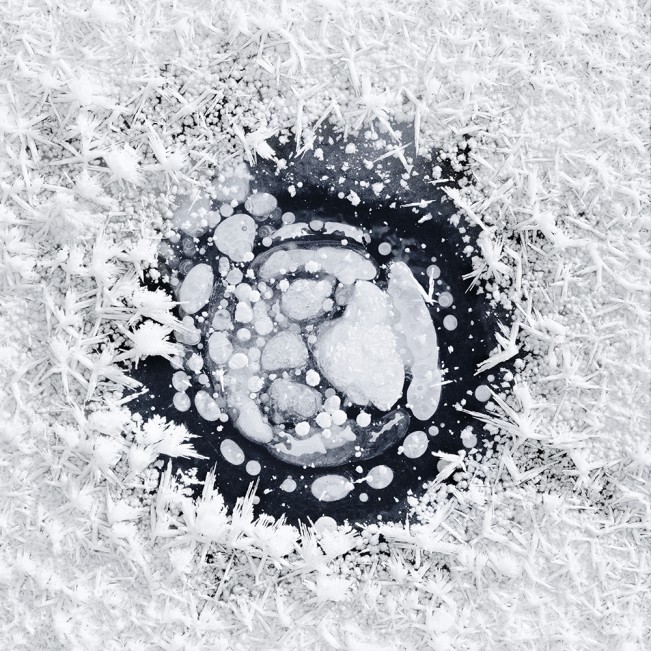

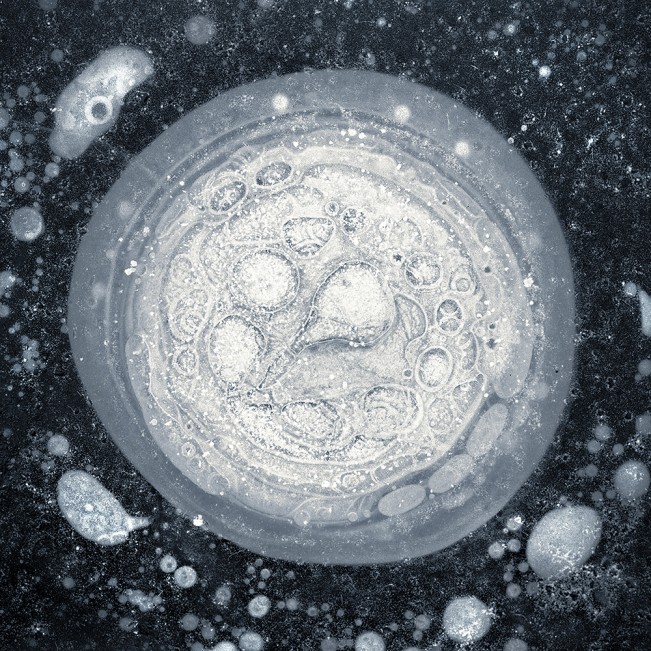

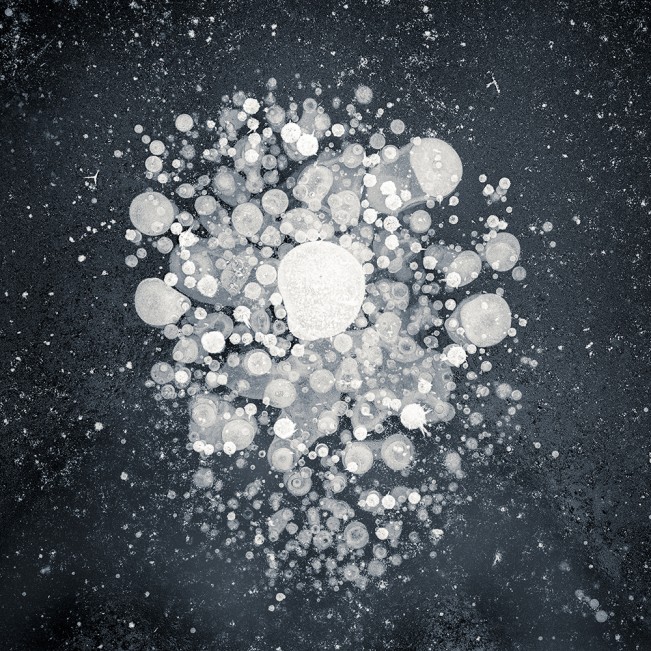

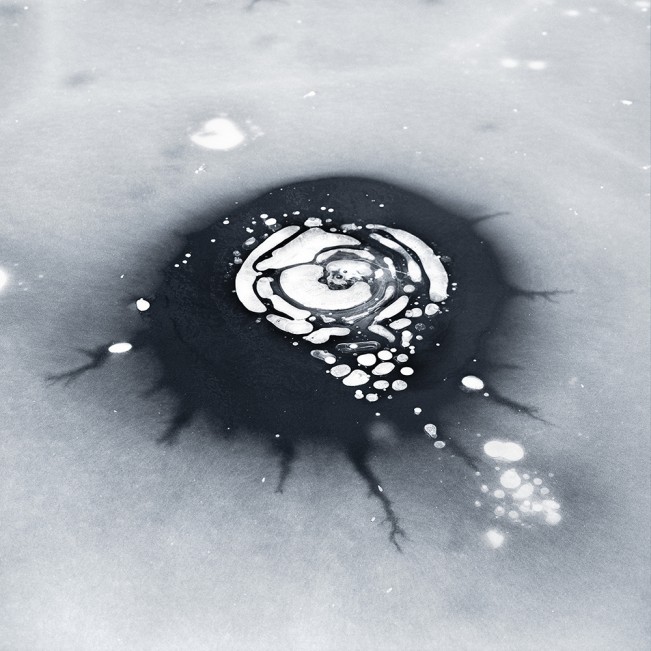

Kaji and I moved to Fairbanks around the same time, and it seemed to me then, that I often heard people talk about this great Japanese photographer who was quietly making good work in Fairbanks. It wouldn’t be until a couple years later that our paths would cross – at an exhibition maybe. The timeline is foggy. But, I’ll never forget the first time I saw his Ice Formation pictures. Sometimes, you see something so simple, so clear, and so devoid of any cynicism or self-consciousness, that you’re dumbstruck. I felt this way when I first saw these pictures. Winter in Fairbanks is harsh business, and even at it’s best (and there are many wonderful things about winter in the Interior) there are moments of great doubt. Kaji was playing with elements in a way that seemed fresh and timeless at the same time. And, he gave me something to think about, and look for, when we were in the grips of winter.

Kaji and I moved to Fairbanks around the same time, and it seemed to me then, that I often heard people talk about this great Japanese photographer who was quietly making good work in Fairbanks. It wouldn’t be until a couple years later that our paths would cross – at an exhibition maybe. The timeline is foggy. But, I’ll never forget the first time I saw his Ice Formation pictures. Sometimes, you see something so simple, so clear, and so devoid of any cynicism or self-consciousness, that you’re dumbstruck. I felt this way when I first saw these pictures. Winter in Fairbanks is harsh business, and even at it’s best (and there are many wonderful things about winter in the Interior) there are moments of great doubt. Kaji was playing with elements in a way that seemed fresh and timeless at the same time. And, he gave me something to think about, and look for, when we were in the grips of winter.

Ryota ‘Kaji’ Kajita was born and raised in Mizunami, Gifu, Japan and has lived in Fairbanks, Alaska since 2005. He completed his MFA degree in photography at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and works at the University of Alaska Museum of the North as a collection photographer. His photographs have been exhibited in the Japan Professional Photographers Society Exhibition (2011), Alaska’s Rarefied Light (2012 & 2013), The Aesthetica Art Prize (2012 & 2013), Aperture Summer Open (2014), Geo-Cosmos Content Contest (2014) of The National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation and other shows. His work became part of the Seattle Office of Arts & Cultural Affaires and The Alaska Contemporary Art Bank in 2013. He was also selected for Blue Sky 2013 Pacific Northwest Photography Viewing Drawers Program (“Drawers”) of the Oregon Center for the Photographic Arts and won the Grand Prize in ONWARD Compe ’13 International Photography Competition, the Student Abstract Category Award in 2013 American Aperture Awards (AX3) and Juror’s Selection / Director’s Honorable Mention / Livebooks Website Award in Natural World 2014 Nation Wide Juried Photography Competition.

His photography series of “Ice Formation” is featured in the magazine “Photo Technique” (November/December 2012) and is represented by Susan Spiritus Gallery in Newport Beach, California.

What is your history in Fairbanks? Did you initially come here to be a photographer?

To live in this vast wild land, Alaska, was the primary aim. There was no concrete vision to be a photographer or something else in my mind at that time. Simply, I had been absorbed in the idea to spend much time in Alaska since I visited an Alaskan native village called Shishmaref in 2002. I vaguely thought that it would be fantastic if I could work in visual mass media because I had worked in a TV station in Japan. However, it was not a critical factor. The easiest way to stay legally in U.S for a long span as an alien was to study in a university in the U.S., so I chose to become a student of the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Pure desire to live in Alaska made me move to Fairbanks.

Most Alaskans know the work, and story, of the great Japanese photographer Michio Hoshino – has he been a great influence of yours?

Absolutely. Hoshino’s work, especially his writings, urged me to visit Alaska. Hoshino has been famous for his wildlife photographs, but also, he left quite a few writings talking about his experiences in Alaska. They are filled with the joy of encounters with both wildlife and Alaskan people and were very touching and inspirational for me. Hoshino seems to have lived a full life and established his own view of life in Alaska. Although he was tragically killed by a brown bear in Russia in 1996, Hoshino’s stories told me that “Life is shorter than you think. Do what you want to do”. I longed for seeing and touching Alaska with my own eyes and hands and traveled to the remote native village of Shishmaref, on Alaska’s west coast in 2002. The Village was the first village Hoshino visited in Alaska and luckily enough, I was able to stay there for three months because Hoshino’s widow, Naoko, introduced me to the family Hoshino lived with. Michio Hoshino was one of the biggest inspirations to lead me to Alaska and also, I truly appreciate Naoko Hoshino’s generosity that enabled me to open the door to the native village in Alaska.

You’ve spent time in over fifty remote Alaskan villages, doing scientific research. These are parts of the world that so few people see, even other Alaskans. How has this experience shaped you as a photographer?

Traveling wilderness in Alaska by snowmobile and flying all over the Alaska by a small propeller airplane made me realize Alaska is huge. The awareness naturally leads me to think that our planet, the earth, is tremendously large. This realization sounds very simple, but it’s truly hard for us to recognize it in our daily life. At the same time, I feel that Alaska is too enormous for me to convey the vastness through photography. The prominent photographer Michio Hoshino succeeded to show the bountifulness and profundity of Alaska wilderness by depicting wild animals as his main subject. However, I feel that I have no capability to do like Hoshino. Furthermore, it is not very meaningful to follow Hoshino’s path and photograph as he did. There is no progress if you blindly follow your ancestors’ paths. So, I felt that I need to find my original way in the art of photography after traveling remote Alaskan places.

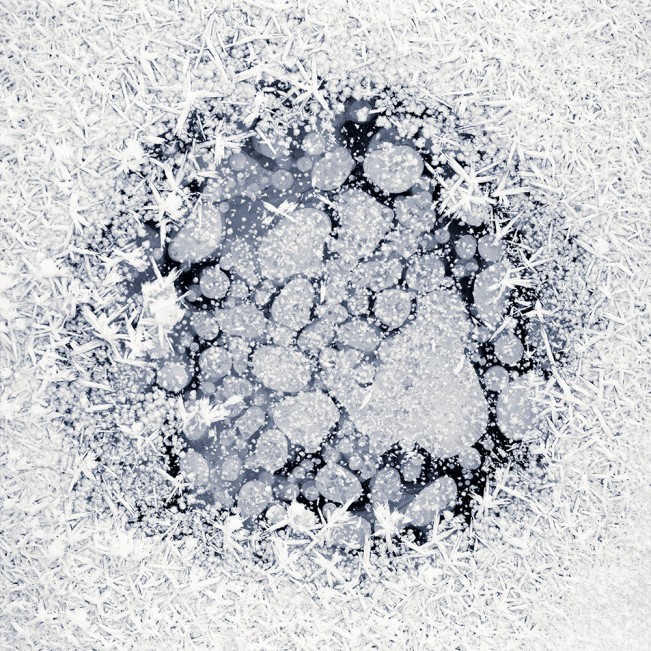

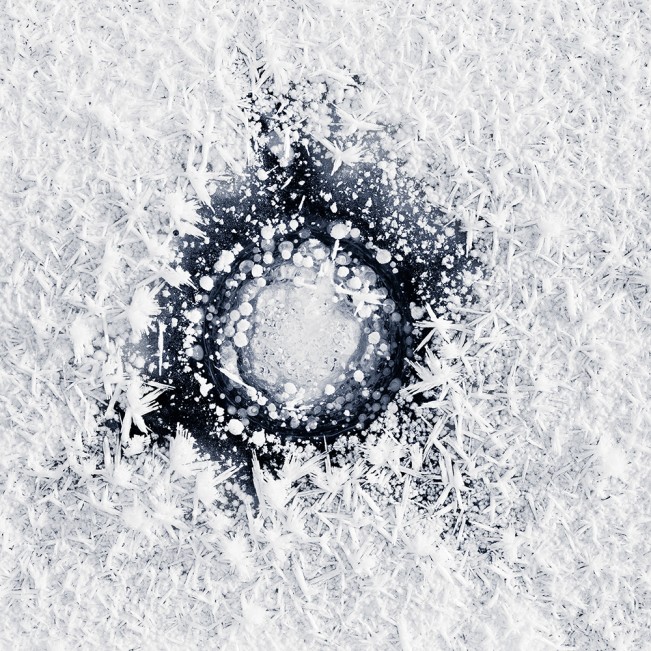

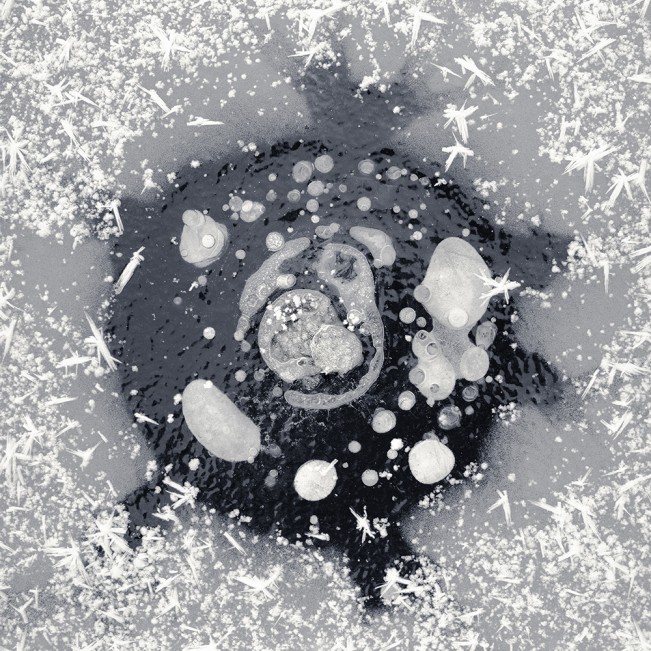

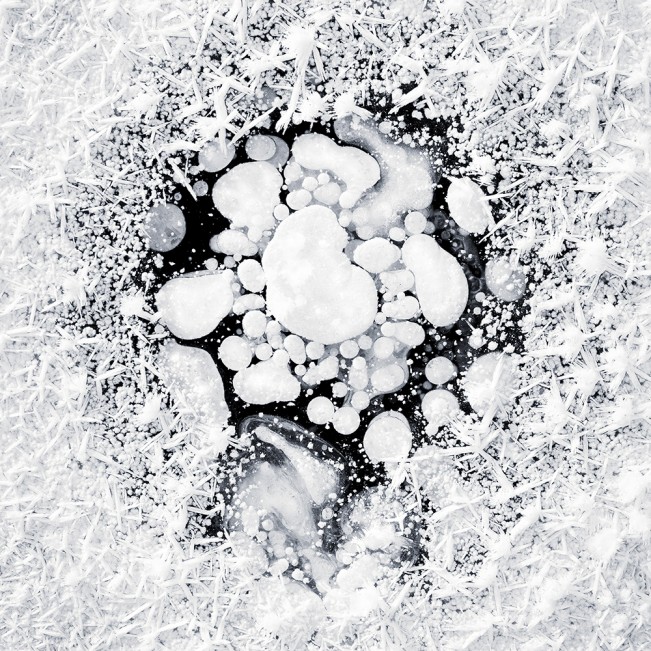

Can you speak about your Ice Formations work?

This series captured natural ice formations on ponds, lakes and rivers in Fairbanks, Alaska. These forms are frozen bubbles of gasses like methane or carbon dioxide trapped under ice. The diameter of the ice formations in these photos is about 10 to 30 inches. Because methane gas is considered as one of the fundamental causes of greenhouse effects, scientists in Alaska are researching these frozen bubbles in relation to the global climate change. We see various forms of water throughout the seasons in Alaska. The images of dynamic changes of water make viewers feel connected to nature. In our everyday life, there are beauty and wonders. However, many of those are subtle, ephemeral or too small to be noticed. If you pay attention to your surroundings, take more time to observe, and examine from different angles, nature reveals their secret beauty to us. I hope my images would inspire viewers to open their mind to new ways of seeing the world and to be aware of the precious harmony with human and nature.

Having watched your Losing Ground short documentary, I can’t help but see climate issues at play in the Ice Formations work. I keep remembering scenes of a UAF researcher lighting methane on fire as it bubbled up from Smith Lake, in Fairbanks, a few years ago. Your typeology seems to be reacting to a similar state of things.

Wandering around looking for ice patterns stems from my innocent curiosity rather than from the view of the scientific approach. While I enjoyed walking with my wife, I found these ice formations and photographing them was fun activity like a treasure hunting. I believe that exploring the neighborhood and leaving your footprints is the first and important step to know a wider environment. Genuine curiosity toward your surrounding environments leads you to get involved in the place you live more actively. That vital dialogs between surroundings and you develops your thoughts how you live on the place, and might be end up to sincerely face bigger issues like global climate change. Everything, even if it looks a tiny thing, connects each other and is composed of our earth.

I wasn’t able to make it to your thesis exhibition at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, but I saw installation pictures and it looked like a really unique experience. What led you to displaying the Ice Formations work on the floor in the manner that you did?

The main reason was to mimic my actual experience of looking down and finding these wonderful ice patterns, at this size, in nature. Seeing pictures hanging on walls is a relatively passive activity, however, the framed images put on the floor forced viewers to bend their necks or knees to look the details. The framed images placed on the floor invited viewers to walk around the whole gallery space. These movements cause more active involvement between my images and viewers. I wanted to produce a dynamic space to explore my images, feel fun and excitement and wonder the beauty of nature as I discovered the ice patterns. Furthermore, it would be the greatest pleasure if my images would inspire viewers’ curiosity to natural phenomena and to admire geometric beauty in the details of the organic patterns.

How do you think living in Alaska has impacted your photography? Do you think you would be making different work had you stayed in Japan?

Living in Alaska totally changed my life. I met some great photographers/professors in the University, and the encounter made me decide to be a photographer. Living in the U.S., apart from my home country, made me to become more keen on expressing my Japanese view in the art of photography. Although it sounds ironic, it would be more difficult to pursue my distinctive esthetics, which I have been naturally inherited as a Japanese if I remained in Japan. Living as an outsider in a foreign country inevitably brings out your indigenous sensitivity whether you like or not. It is important to seek your root and inspirations in your own mind.

Do you feel that having a photographic community is important? What are your impressions of the community in Alaska?

I am an intrinsically shy person, so the cowardice has prevented me from having any connection to a photographic community except the professors at the university and very few others. Now that I graduated from the university, I need to connect with other photographers in Alaska and other states.

Do you and your family plan to stay in Fairbanks?

My daughter was born in Fairbanks two years ago, and my lifestyle has changed and every minute is controlled by her since then. So, I have to ask my daughter our future plan.

Do you ever have dreams of living, and making pictures, somewhere else?

Buy an RV, travel all around the United States, camp and hike in national parks and photograph what I see.

Finally, what’s next for you? Do you have anything new that you can share with us?

Keep photographing. This simple thing is important for my future as a photographer. We are living in the digital age and having a camera and taking photographs is not a hobby exclusively for rich people, nor an expertise job of skillful professionals anymore. You might be able to photograph a decisive moment in human history by your cell phone without any knowledge of the camera. Furthermore, you are able to relatively easily enjoy the historical photographic processes like tintype, wet collodion or other forms. The aid of computer makes the process more easily accessible. We enjoy receiving benefits from the technology advancements and are living in a pivot time in photography history. We are in a great epoch everybody can be a photographer. However, keeping to be a photographer is difficult. In this circumstances, to keep photographing, explore the medium and search for the better way to sublimate your personal feeling and esthetics into a universal appreciation is critical. In that way, I can call myself a photographer and live my own life.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Naohiro Maeda: Where the Wild Things AreDecember 26th, 2023

-

Adam Ottavi: The States Project: AlaskaMay 2nd, 2015

-

Ryota Kajita: The States Project: AlaskaMay 1st, 2015

-

Chris Miller: The States Project: AlaskaApril 30th, 2015

-

Brian Adams: The States Project: AlaskaApril 29th, 2015