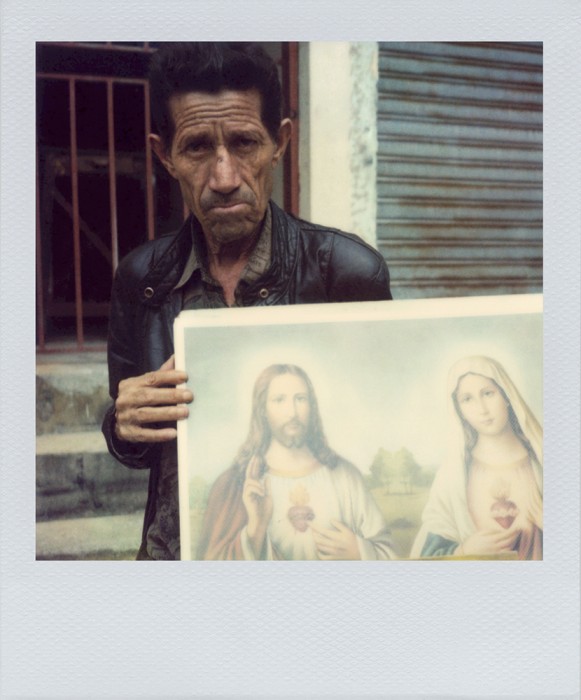

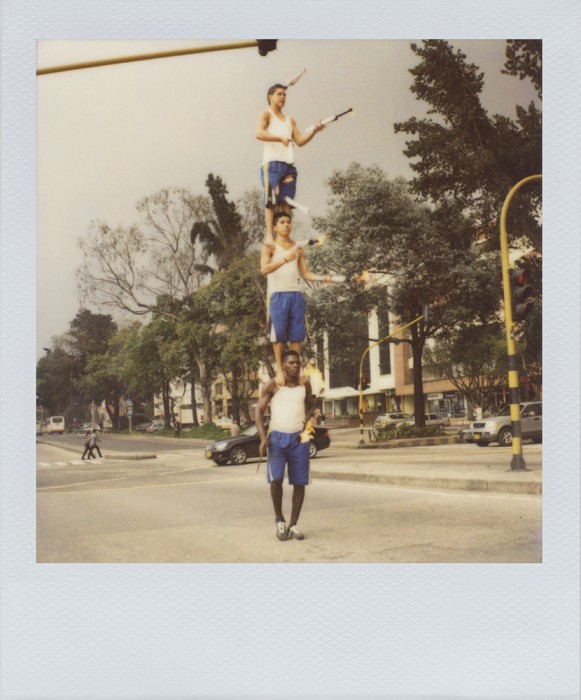

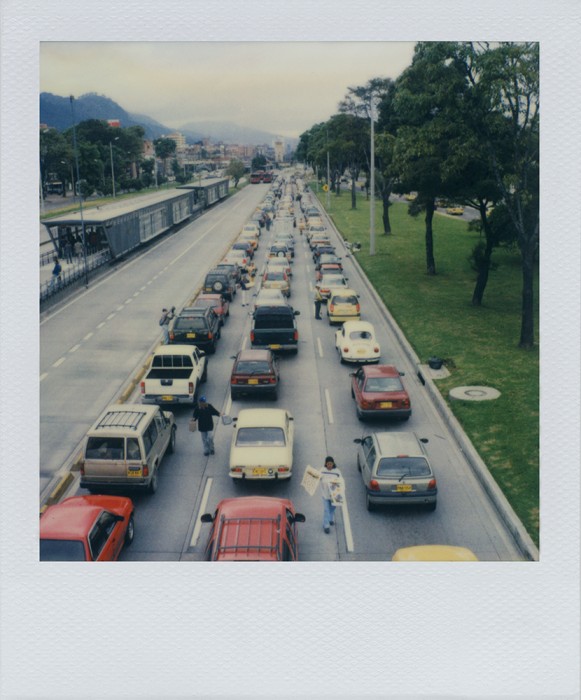

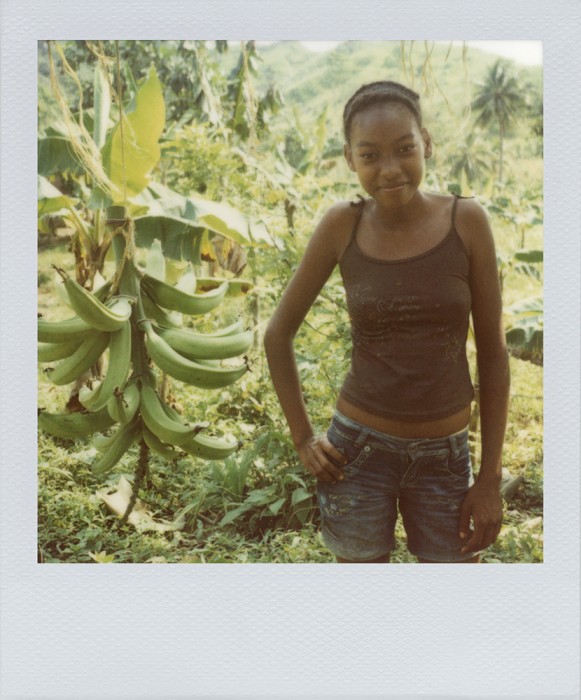

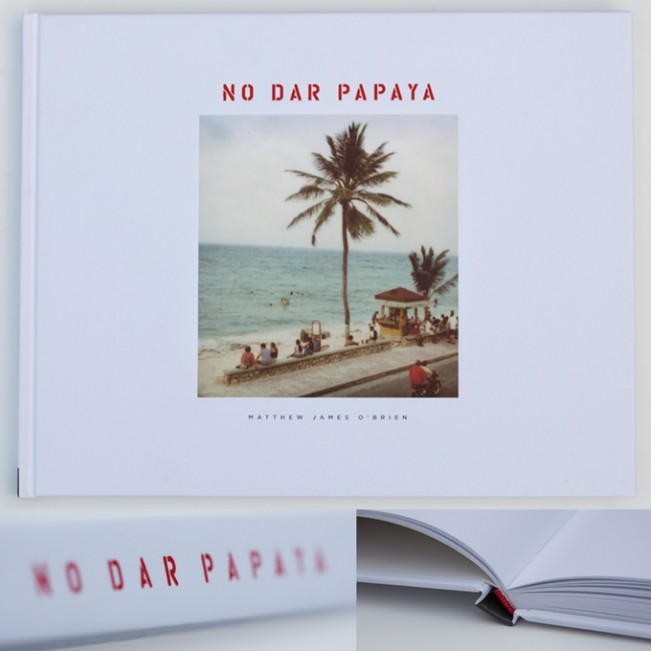

Matthew O’Brien: No Dar Papaya

Many of us have a vision of Colombia, and it’s not necessarily a positive one. Photographer Matthew O’Brien wants to change our perceptions through a series of Polaroid images titled No Dar Papaya. As Matthew states, “Colombia is a fascinating, beautiful country with tremendous geographic and cultural diversity. Internationally, however, that is not how the country is portrayed. Before first traveling to Colombia in 2003 to photograph, friends and family in the US were concerned for my safety. My mother cried because she thought she might never see me again.

To be sure, there is an armed conflict in Colombia, now in its fifty-first year, and the illicit drug trade has had far-reaching effects on Colombian society. Over those five decades, many thousands of people have been killed and displaced by violence. But, there’s so much more to Colombia than ubiquitous stories of violence, desperation, and misery might lead one to believe.”

Matthew’s project, No Dar Papaya offers a different vision of Colombia, one that recognizes the beauty in the everyday. He has also created a book with the same title and needs our help to realize the publication. He has a Kickstarter campaign worth checking out.

Matthew, who is based in San Francisco, has been making photographs that explore social issues and celebrate humanity and the natural world for over twenty years. His work has been exhibited and collected by a number of institutions, including The California Museum of Photography; the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; the Library of Congress; The Fries Museum, Netherlands; and the Museo de Arte Moderno de Cartagena. Among the awards he has received are a Fulbright Fellowship, a Mother Jones International Fund for Documentary Photography Award, and a Community Heritage Grant from the California Council for the Humanities.

Matthew, who is based in San Francisco, has been making photographs that explore social issues and celebrate humanity and the natural world for over twenty years. His work has been exhibited and collected by a number of institutions, including The California Museum of Photography; the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; the Library of Congress; The Fries Museum, Netherlands; and the Museo de Arte Moderno de Cartagena. Among the awards he has received are a Fulbright Fellowship, a Mother Jones International Fund for Documentary Photography Award, and a Community Heritage Grant from the California Council for the Humanities.

Past projects include Back to the Ranch, his exploration of one of the oldest ranching communities in the United States, across the bay from San Francisco, and its demise due to urbanization, and Looking For Hope, his collaborative study (photos by him, texts by students) of growing up in the inner city and the public school experience in Oakland, where he taught for several years. In addition to creating photographs, he teaches photography in both English and Spanish.

No Dar Papaya

No Dar Papaya is my photographic exploration of Colombia created from 2003-2013 with a Polaroid camera and film. Though there are many challenges to working with this equipment, Polaroid film no longer manufactured being one of them, I use it because I like the softness and the distinctive color pallet of Polaroid; it works well with my experience of Colombia.

The work is an alternative vision of Colombia– alternative to the images of war, violence, and misery that dominate imagery from the country in the international media. That kind of imagery, known as pornomiseria in Colombia, is not what interests me as a photographer, and it doesn’t represent my experience of the country, where I find lots of beauty, warmth, and humanity. This work reflects my experience of Colombia and is my endeavor to convey some of the beauty, diversity, creativity, and otherworldliness that I find there.

The images come from all over Colombia, from the big cities to rural pueblos, to Caribbean islands, to remote forests, deserts, and high mountain peaks. They are part of a much larger series that includes a diversity of images, the idea being that together the variety of images provides a broader picture of Colombia. The series doesn’t pretend to give an overview of the country, but rather a personal collection of snippets, moments, individuals, and places that together speak of realities and possibilities in Colombia.

The title, No Dar Papaya, is a common expression unique to Colombia which means show no vulnerabilities and present no easy target. It speaks to the reality of life in Colombia, now in its 51st year of war. Tens of thousands have been killed and hundreds of thousands displaced from their homes. Unspeakable cruelties continue to happen. It has a rigid class structure and the greatest disparity between haves and have-nots in Latin America. There’s lots of crime in the cities. Amid this, people live their lives with lots of creativity, joy, humanity and beauty, and that is what interests me.

Last year I had the opportunity to share the work with the Colombian public through a series of exhibitions and the publication of a book. I am looking forward to the book being published in the United States this year.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: jessamyn lovell: How To Become InvisibleFebruary 9th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026