David Hilliard: Sum of Our Affections

The Provincetown Art Association and Museum (PAAM) has opened a mid-career exhibition celebrating the photographs of David Hilliard. David, well know for his multi-framed panorama technique, is a master in narrative and at giving life to the still image. His work, living in between his known truth and his projected fiction, is directed by events in his life, the people he has met, the people he has loved. Though the work comes from a personal place, David’s photographs allow the viewer to converse as if they were our own intimate conversations or chance encounters. We are able to access the photographs in terms of time and place, allowing for an enveloping viewing experience.

It was a pleasure to be able to speak with David about his life, his process, and his thoughts on his work since he began photographing.

David Hilliard: Sum of Our Affections, curated by Bill Arning, runs July 8th through August 28that The Provincetown Art Association and Museum.

David received his BFA from the Massachusetts College of Art & Design and MFA from the Yale University School of Art. He worked for many years as an assistant professor at Yale University where he also directed the undergraduate photo department. He is a regular visiting faculty at Harvard University, the School of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Massachusetts College of Art & Design and Lesley University College of Art & Design. David also leads a variety of summer photography workshops throughout the country.

Hilliard is represented at The Schoolhouse Gallery in Provincetown, Massachusetts, a producing partner in this exhibition.

Since the early 90’s you have been photographing lush and narrative fueled multi-framed pieces that have truly become a real signifier of you and your art practice. Since then you have had countless solo exhibitions and a monograph to your name. Throughout the entirety of your practice, what would you say you have learned from this work?

That’s a big Miss America question but I think I can answer it honestly. I think I’ve learned and/or confirmed that the act of photographing continues to be the clearest way to see and experience so much of what intrigues me, haunts me, angers me, and perhaps holds what is unobtainable within the realm of my daily life. The camera seems to be the best mediator of the way I see, feel and think. It’s a decadent tool; to stare with, possess that which I cannot have, say what I cannot speak, ponder that which confuses me and so on. It’s my visual petri dish. I’ve also learned that you never really run out of subject matter if you just stay open, present as they say. I’ve also learned that my projects never really end…I just keep adding to them. They’re linear but linear in a forward sense as well as a left to right. The stories, much like our lives, just keep plodding along. Does that make sense?

Yes, so what you are saying is that your practice directly parallels with your life in which you are photographing a singular indefinite body of work. Is there something that has led you away from the 15-20 image structure?

Yes, my work and my life, in general, run in tandem. I document ongoing relationships, themes (masculinity, sexual identity, working class lifestyle, father/son relationships, strangers and such) and the serendipitous nature within the quotidian. The bookended project has always just felt a bit too buttoned up for me. Don’t get me wrong…I love SO MANY projects but have never been able to work well within that model.

Picking up a camera as a kid must have come easy for you. Growing up with your father constantly photographing your childhood, and then in turn using a camera to document your very mobile upbringing. Are you able to pinpoint the moment in which the camera became less of a journal and more of a tool to make art?

Yes, the camera was a device that I grew up around (less common in the analog ages) and I saw it used in some very interesting ways. The most interesting and perhaps formative was my dad’s obsessive documentation of certain mundane family rituals, like coming through the door. “Through the door shots” were classics. My father, much like a hunter, would often be in wait for us to come home from school, in from playing and such, snapping our surprised expression as were arrived home. These images like everything else was catalogued, dated and given some sort of “field note”. Basically my entire life has been chronicled in images and journal entries from the day I was born. I could tell you what I was doing on June 9th 1987 at 3pm. No joke.

To answer your question, I think taking photographs became making photographs during my sophomore and junior years of college at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design in Boston when I became fully immersed as a photo major. Prior to that I had bounced around exploring lots of other mediums; theater, fashion design and film, all of which continue to feed my process. During my years as a photo major I worked with some AMAZING artists and educators at MassArt; Laura McPhee, Abelardo Morel, Barbara Bosworth, Nicholas Nixon, and Frank Gohlke among others. Each of them left such an impression on me regarding form, content, and ultimately what it meant to truly make photographs and live life as a fully formed artist. Some crazy great years. The best. Later, an MFA at Yale School of Art sealed the deal, but that’s another story.

You mainly speak about your work blurring the lines between truth and fiction – autobiographical, but not a memoir. Where does the desire in romanticizing fiction come from?

Well, there is for sure a balance within my work. The world as it is, people that I know (family, friends, lovers), strangers, landscapes that I traverse. And at the same time all of these “truths” if you will, are seen through my camera with varying degrees of staging, dramatic visual play, augmented qualities of light and so on and so on. Much of the fictive aspects are my wanting the world to look a certain way perhaps, or wanting you to notice (hence the exaggerated optical seduction) that you might not notice otherwise, wanting to change your mind, wanting you to see the beauty, pain, dignity, importance that I see in the world. Really, that could be said of any artist. I think with photography that isn’t “straight” photography often has to explain its subjective flourishes, in quite a different way that artists in other mediums do, or are not even asked to explain. Photography, all these years later, is still sometimes trying to push back against certain expectations.

Structurally, each piece functions as a multi-framed narrative, which perhaps can be attributed your film background. Film has a tendency to divulge more sensory information primarily because of its time-based structure, something that a photograph is limited to. How would you say your work functions as film?

It’s pretty simple actually. Many artists explore multiple images/the panorama, but in my case it truly is a dense hybrid of many of the influences within my life – a confluence of theater, history of painting, film, fiction writing, and art therapy – all mediated through the lens. So my high key performative/tableaux images live between the static still photo and a moving cinematic strip of film. Images shift in time, focus, and mood. Ultimately, in theory, I present a single moment but it’s actually comprised of multiple moments in time, a continuum, that as a whole present a scenario to the viewer. A scenario that lives between fact and fiction, the personal and the universal. I hope my images are open-ended enough that the viewer can project their desire, history, judgment and such into them…finishing the story.

What piece resonates over the others?

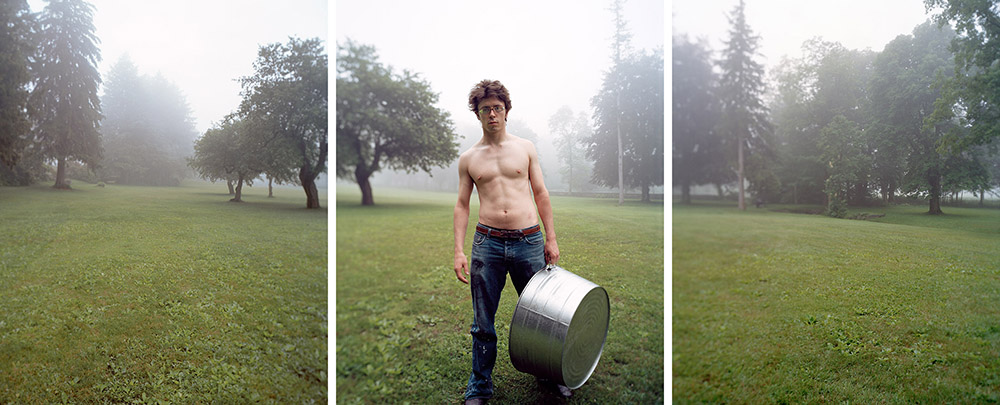

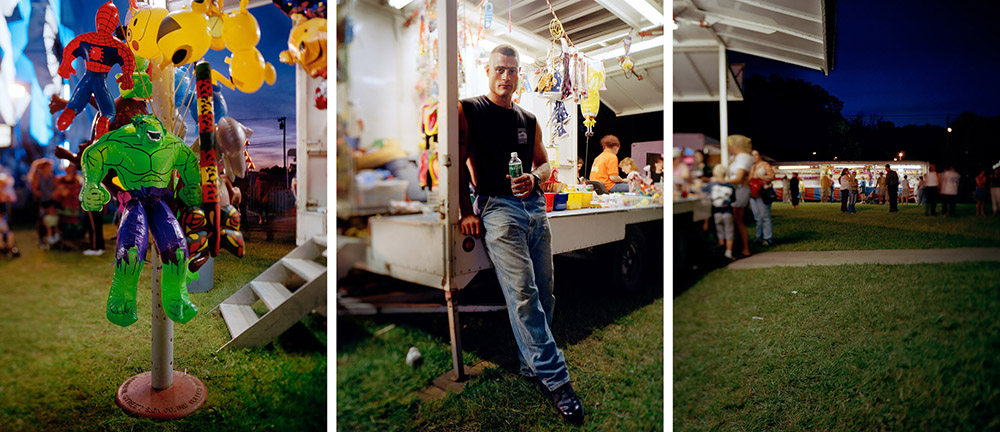

My favorite images tend to shift. Some of my personal favorites, ones that I’d hang on my wall (although I never hang my work in my home…to stressful), are in exhibition at PAAM; Hulk, Rock Bottom, Boys Tethered. They satisfy me in terms of their formal qualities as well as holding many of the conceptual aspects of my work that I’ve spoke to. I’ve also always loved an early image of my dad titled The Lone Wolf…a shot of my father reading Playboy at home in bed. A very simple image but one that holds up and remains the heart of so much of the work that I’ve made, and continue to make, with him.

You have spoken about coming out during the height of the AIDS epidemic within the gay community. Such an informative period, and finding oneself was probably never riskier. Would you say that all of this — the risk, the loss, even the comfort — finds a place among your work?

Regarding coming of age in the shadow of AIDS, yes, it was tough. I speak to it in depth in this recent interview (David Hilliard, A and U Magazine) where I speak to my formative years being filled with lots of loss, fear and shame due to the AIDS epidemic. I know that it’s impacted my work, and most certainly has impacted my identity. I do have some images that directly address the epidemic, others allude to it (fragility, references to blood, loss and longing). It’s so wonderful that we all can live with less fear around HIV/AIDS but I evolved in the years were you didn’t live with it. I lost many friends and much of my life is lived for those I lost. My work honors them and celebrates the preciousness of being alive.

Finally, I’d also like to say just how meaningfully it is to have this exhibition at PAAM. It’s very symbolic for me. Provincetown has been a place that I’ve returned to again and again throughout my life and has always been impactful. As a young boy I went there with my family. In the 80’s I came into my own as a gay man there, spending two summers running amok and finding myself. Those years are also a bigger conversation about HIV/AIDS, so much fear and loss mixed in which so much joy of coming into ones own. I was there (during my second summer living there) when I received my letter of acceptance to MassArt in Boston. I knew then that my life was changing is ways it needed to.

I later went on, years after undergrad, to an MFA at Yale, a Fulbright that kept me in Spain for three years, and then to work with the Schoolhouse Gallery where I continue to show today. I’ve also been teaching at the Fine Arts Work Center for many years (can’t believe I keep getting asked back…it’s dreamy) ,and last summer was invited to be an artist in residence with 20Summers and got to spend a week in the Hawthorne Barn making work (one of the images, Vapor, in the PAAM exhibit is from that week). It’s been decades of returning to a town that has continued to embrace me or just simple ALLOW me to be who I am. Go Ptown…you had me at hello.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: jessamyn lovell: How To Become InvisibleFebruary 9th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026