John Lusk Hathaway: The States Project: South Carolina

Although we have yet to meet in person, I feel in some ways I know John Lusk Hathaway by the kind of images he makes—down to earth and honest.

For five years now John Lusk Hathaway has been traversing the low country in South Carolina, making connections, driving back roads, taking his time with folks, sometimes with a camera and sometimes without. All the while gaining trust and listening to stories so he can make pictures. It is no wonder his perspective makes us feel we are both a part of while at the same time acknowledging we are not from.

John Lusk Hathaway was born in Memphis, Tennessee. He received his MFA from East Tennessee State University in May 2012. John was nominated for the 2014 Baum Award and was the recipient of the Individual Artist Fellowship Grant from the Tennessee Arts Commission the same year. He was a finalist in Review Santa Fe and a semi-finalist in the Duke Honickman First Book Prize in 2012. Hathaway is currently photographing the state of South Carolina and southeast at large for The American Guide Project. He is a lecturer of photography at The College of Charleston in South Carolina.

Archaeology Of Water

“Water has its own archaeology, not a layering but a leveling, and thus is truer to our sense of the past, because what is memory but near and far events spread and smoothed beneath the surface.” – Ron Rash from Nothing Gold Can Stay

Walker Evans pioneered the lyric documentary style nearly 80 years ago, and in doing so stated, “I’m sometimes called a ‘documentary photographer’ but… a man operating under that definition could take a sly pleasure in the disguise. Very often I’m doing one thing when I’m thought to be doing another.” This could be the most powerful thing a well-resolved photograph, one with a solid idea and structural elements, can accomplish. The viewer is inclined to believe what they are seeing to be true, especially when the photographer is astute at using a camera that is capable of resolving an incredible amount of detail.

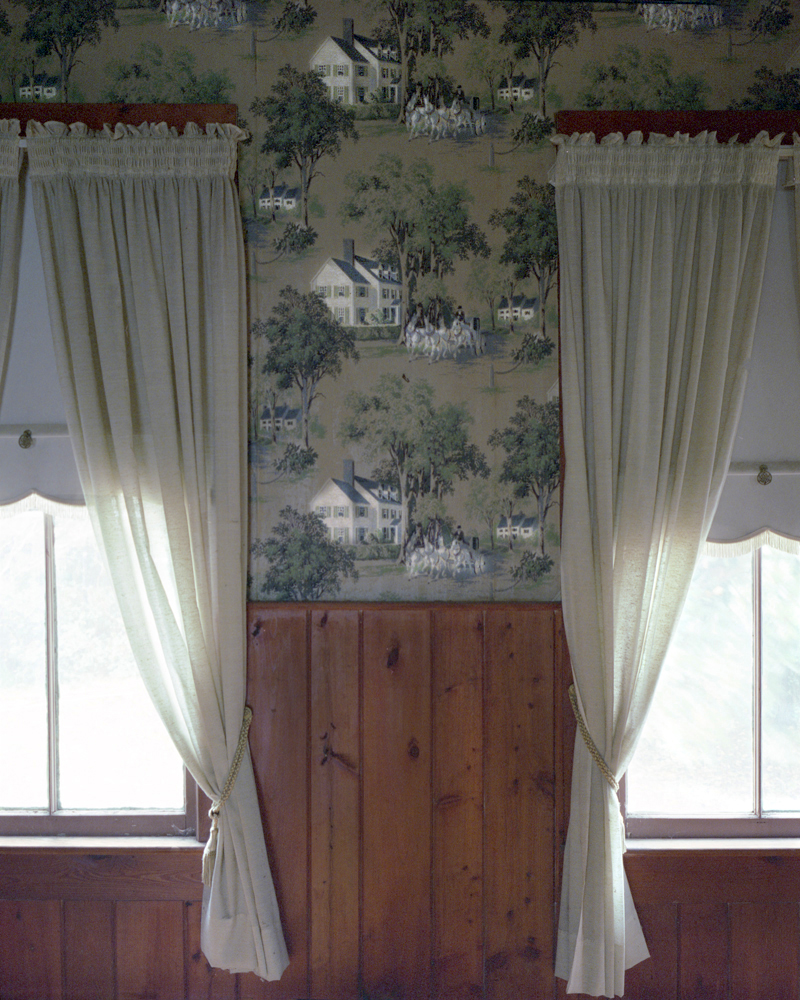

With this in mind I have been photographing the landscape and people of South Carolina’s barrier islands and salt marsh communities with an eye for the transparent and poetic. The constant ebbing and flowing of the mighty Atlantic and her tidal estuaries create some of the richest and most productive land on earth. So much so, that it even seems to dictate the pace and trajectory of human life in areas that are far enough removed from the distracting rhythms of the city to be receptive to it.

The rural periphery of Charleston has been a rewarding place to make pictures; the storied landscape (part factual -part legend), continues to mystify and confound, ultimately shaping and driving the overriding poetic narrative in the work. This is my attempt to make photographs in a landscape that is informed, but not bound by history (American and photographic). Great works of art pertaining to the human condition and environment run a gamut of emotions, and I aspire that these photographs are no different, beauty, desire, loss, despair, and hope are all present, but in subtle and rewarding ways. Life is full of contradiction; here we see a historic landscape and culture fighting for autonomy and melding seamlessly with modernity in the same frame.

This work is not a documentary in the traditional sense of the word, but it does rely on similar tropes to visually relay ideas in a way that seems familiar and true to the viewer. The work occupies a gray area between fiction and non-fiction, art and documentary. The people and places I photograph are real, but the sequence and narrative I create are wholly subjective. I am motivated to make photographs that transcend what is actually photographed ultimately offering the observer a personal narrative of the extraordinary land and people of the tidal basin.

Both your projects One Foot in Eden and the Archaeology of Water are about man’s relationship to the environment, do you think your own personal relationship to the natural world has been transformed by these projects?

I am definitely more aware of certain aspects of our collective relationship to the land because of my work in Tennessee and South Carolina, but I don’t necessarily think my personal ties and exchanges to the environment have changed. Reconfirmed and enriched in some ways, but not changed.

I was born in Memphis, but at a young age my parents moved our family to be around relatives on the opposite side of the state. Upper East Tennessee was a vastly different place in terms of landscape, population and culture. One of the first significant things I noticed (when I was old enough to recognize larger ideas and themes of the world) was that the land in some form or another heavily influenced most people who grew up in Appalachia. The culture was bound to it. It is hard to speak of the region without in some way talking about the land — it is part of the collective identity. This held true for those I was closest to as well. My family would spend a significant amount of free time camping and hiking in Dennis Cove and what is now the Pond Mountain Wilderness tract (both of which were photographed extensively in the series One Foot in Eden). Out of this I developed an appreciation and respect for the beauty and solitude the temperamental ecosystem afforded, but I also began to see a larger picture emerge. I started to understand that we as humans are just a small piece in a large and spectacular ecosystem. It is sometimes easy to forget in the fast paced post — Internet egocentric world that we live in, but I feel it is imperative that we seek to understand, not only our place, but also the intrinsic and elemental pull we have toward our natural environs.

What is the most surprising thing you have unearthed while making either body of work?

Honestly there are many photos, ideas, and themes I have “dug” into but if I had to choose just one, I might turn things around and say that photography actually “unearthed” something in me. I was painfully shy throughout my adolescent and teenage years. As one can imagine I was very much an introvert, especially around large crowds, and even smaller groups when I did not know many people. Because of this I became an obsessive observer of both people and the general world around me.

Photography was a natural step for me to investigate my surroundings. It gave me a certain freedom to be places, places where I normally wasn’t comfortable. It was liberating. The camera served as a buffer for situations that would routinely give me anxiety. When I became serious about photography, serious enough to pursue an MFA and start the photographs that were to become One Foot in Eden, I came to the uneasy conclusion that to strengthen the work I needed to make portraits. With practice I was making a few nice landscapes, but when I would edit pictures, the only ones I would think about were the ones of people that I didn’t photograph. So the pictures I was obsessing over were the ones I didn’t have the courage to take – I knew this had to change.

I started making portraits. Anyone that was remotely interesting, I would ask to make his or her picture. I was shocked that most people said yes. I also realized that when someone grants you permission to make a portrait that is only the first, and easiest step in the process.

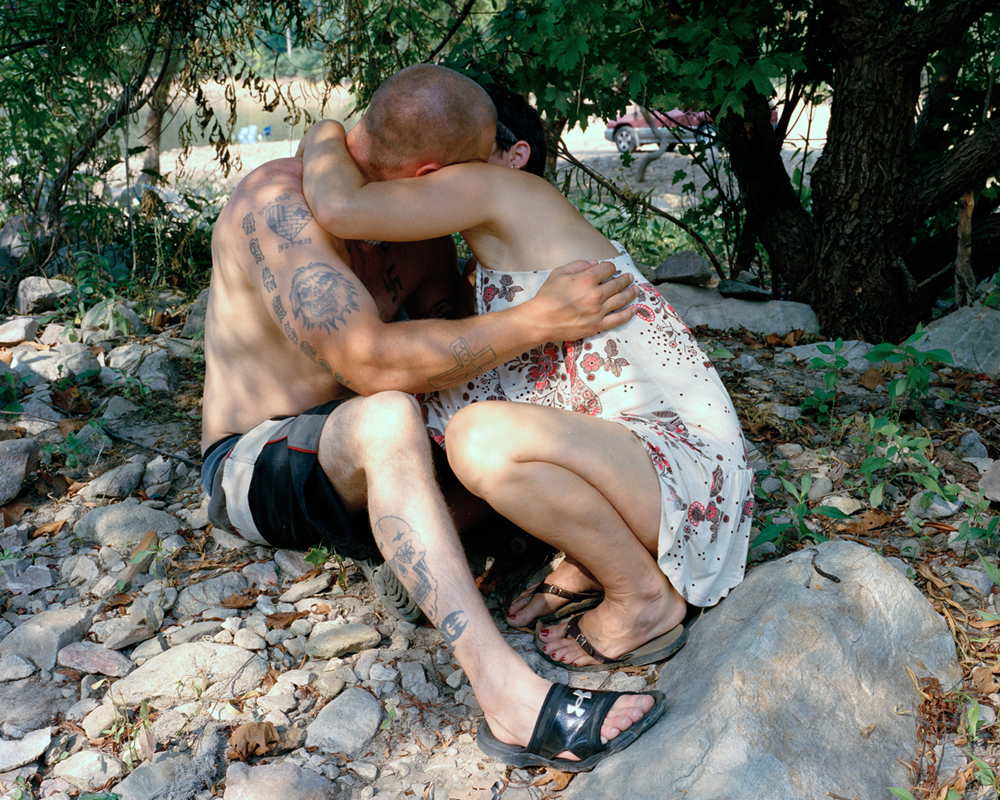

A strange dance occurs between the photographer and subject during a portrait. The photographer offers just enough presence not to be obtrusive and when combined with the right distillation of light, air and space, and a subject that is neither to forceful or reserved, magic can happen. This proved to be a rewarding time in my life. I was learning to make portraits, and as it were learning to interact with people, many times strangers in a meaningful way.

How do you go about finding your subjects?

I find my subjects a variety of ways, but a large part of the way I photographed One Foot in Eden and Archaeology of Water was to be out in the environment. Any day that I am free I try to make time to photograph. I don’t think there is a substitute for that kind of engagement. One can prepare and research for days (which I am a strong advocate for), but it doesn’t necessarily translate into pictures. As a photographer one has to be open, as Tod Papageorge eloquently states, “to the mad swirling possibilities that our dear common world kicks up at us on a regular basis.”

You mention that the work One Foot in Eden comments on, among many things, the relationship of “class in America” and the very unique role that the surrounding natural environment plays in these peoples lives, can you expound upon that?

It is hard, maybe impossible to photograph in Appalachia without commenting on class directly or indirectly. Most of the photographs contained in One Foot in Eden are taken in either Carter County or Johnson County. The Appalachian Regional Commission categorizes Carter County as “At-Risk” and Johnson County as “Distressed” in their 2015 Economic Status Report. This basically means that these two counties function well below the national average for three economic indicators: unemployment rates, per capita income and poverty rates.

I was sensitive to this when making photographs. I didn’t want to ignore the fact that these counties face economic hardships, nor did I want to the exploit those hardships. In literal terms of the photography, I didn’t want economic status to be front and center in the images. If it could be gleaned from the images, I wanted it to be on the periphery. I think this affords the viewer a more rewarding experience. It’s hard to navigate a photograph freely, or to let ones own thoughts and life experience pierce the veil of understanding if an idea is too heavy handed or used in an exploitative manner.

In the first question I touched upon the roll the landscape plays in the lives of those in rural Appalachia. It is hard to separate everyday life from the environment. They are intertwined. Many from Appalachia are still providing for their families through subsistence agriculture. Much of the industry in the area photographed centers on agriculture, forestry and mineral extraction. Hunting and fishing for sport is popular in all corners of Appalachia, but in “At-risk” and “Distressed” counties residents rely on the meat as a large source of their daily caloric intake. Of course in One Foot in Eden the realities of those from rural Appalachia are juxtaposed with those of transplants and visitors seeking a beautiful vista and a recreational outlet for the angst post-internet society yields. The underlying themes, questions and concerns generated by the work are paramount in the process of learning about ourselves, and the tenuous relationship we have to the landscape. And again, class is not the central theme in the photographs, but one of many that I hope provide a springboard for further thought and contemplation on who we are as a people and how/why we recruit nature to be our comforting shoulder and adumbration of meaning pointing towards something greater than the singular self.

Are you a “shoot-to-know” or a “know-to-shoot” kind of photographer?

I think both ways have merit. It is more of a balance for me personally. Being open to pictures, or serendipitous moments, has always been important to the way I approach the medium as I stated earlier. Making two dimensional representations of a three dimensional world is a conceptual exercise. Diane Arbus stated, “I never have taken a picture I’ve intended. They’re always better or worse.” It’s just not possible to know how everything will look when you release the shutter. In regard to this I’m “shoot to know.” But then there are times when things align, and your instinct tells you to make an exposure.

In a recent Art21 documentary Robert Adams asserted, “The final strength in really great photographs is that they suggest more than just what they show literally.” This feeds into what I think may be more important than how one photographs. What is the photographers ability to read what their photographs say, and apply that knowledge to an idea or theme in their projects? I think most photographers, myself included, should spend more time editing. It is the only way to achieve crystalline clarity or on rare occasions a transformative vision in ones work.

One Foot In Eden

For as long as I can remember, I’ve been captivated by the tenuous relationship between humankind and the natural world. My early fascination with the ways we shape – and are shaped by – our interactions with natural environments informed and eventually became the focus of my photographic work. Most recently, I’ve explored these ideas by investigating the mechanics of our interactions with Tennessee’s largest tract of publicly held land – the Cherokee National Forest. I have dedicated three years to this inquiry, which has culminated in this body of work.

The federally managed Cherokee National Forest is set-aside for U.S. citizens to enjoy as a recreational outlet and to use as a commodity for the infrastructure of our consumerist nation. Evidence of the tension between commercial interests and the public’s statutory right to ‘enjoyment’ of the land can be found throughout the area. For me, the uneasy relationships between private and commercial notions of land ‘use’ emphasize the complexity of man’s broader impacts on the forest’s ancient and temperamental ecosystem. Amidst these relationships, I see comments on recreation, class in America and the unique role this natural setting plays in the communities of rural Appalachia, an area that has been misunderstood and maligned for generations. I want to describe this tense balance, and in doing so create a catalyst for thoughtful conversation around the expansive and elemental narrative between man and nature.

When elements align, the photographs create a complex stage where the landscape and cast of characters coalesce and vie for attention within the landscape of the Cherokee National Forest. The forest becomes a backdrop where human life is acting out a poetic form of wild living. The photographs continually show the dichotomous interaction we have with this wild space. Exchanges range from mediated and flawed to real and felt, and provide a springboard for further thought and contemplation on who we are as a people and the role of these environs in our complex society. Ultimately I hope they convey my sense that we should seek to better understand this mysterious relationship, and mend our tattered and egocentric affiliation with the wild.

©John Lusk Hathaway from One Foot In Eden

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jen Ervin: The States Project: South CarolinaJuly 22nd, 2017

-

Michelle Van Parys: The States Project: South CarolinaJuly 21st, 2017

-

John Lusk Hathaway: The States Project: South CarolinaJuly 20th, 2017

-

Ashley Kauschinger: The States Project: South CarolinaJuly 19th, 2017

-

Tracy Fish: The States Project: South CarolinaJuly 18th, 2017