Mariana Vieira: The States Project: Colorado

I got to know Colorado photographer Mariana Vieira during the Center Forward Exhibition and Photo Camp that Hamidah Glasgow and I jurored and taught at the Center of Fine Art Photography in Colorado a couple of years ago. Mariana was and is passionate about her craft–her various projects are created with painstaking detail and deep consideration. She shared a piece from her, From P to R series, in the exhibition and I was mesmerized by her miniature masterpieces, work that was placed into the world for serendipitous discovery. Because Mariana is a committed photographer and educator with interest in a wide variety approaches to image making, I knew she would make a terrific Colorado States Project Editor. Today, we feature two of her projects and a short interview with the artist.

Mariana Vieira mines contemporary topics as raw material to construct her work. From an early age, she was aware of how socio-political factors can powerfully transform individual outcome and shape worldview. She was born in Brazil when the country was under a military dictatorship, and grew up among the residues of civil war and of foreign military involvement in Latin America. She uses the act of creating and making to transform material and experience. She has investigated transformation through reimagining optical devices like the praxinoscope and the mutoscope, through lenticular image animations, origami installations, and recently, through transforming an encyclopedia into a series of miniature books to give away to unsuspecting recipients.

Mariana Vieira was born in Brazil and grew up in Central America. She studied photography at Georgia Southern University, where the darkroom became her second home. She relocated to Boulder to study at the University of Colorado, and has called the Rocky Mountain state home since then. Mariana has been featured in exhibitions at Anderson Ranch Arts Center, the Center for Fine Art Photography, and the Colorado Photographic Arts Center, among others. She currently works at the University of Colorado.

From P to R

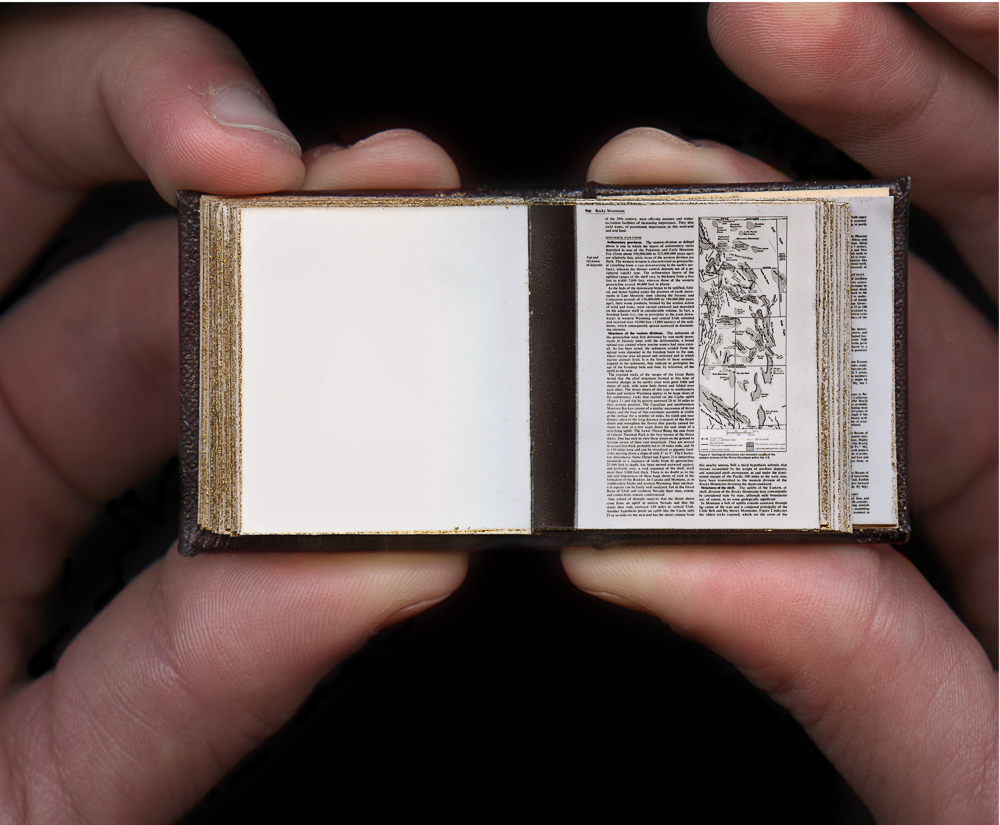

Most people remember leafing through the pages of an Encyclopedia with nostalgia, associating the experience of discovery with the physical act of turning a book page. The Encyclopedia was a source of information, and a catalyst for curiosity and discovery.

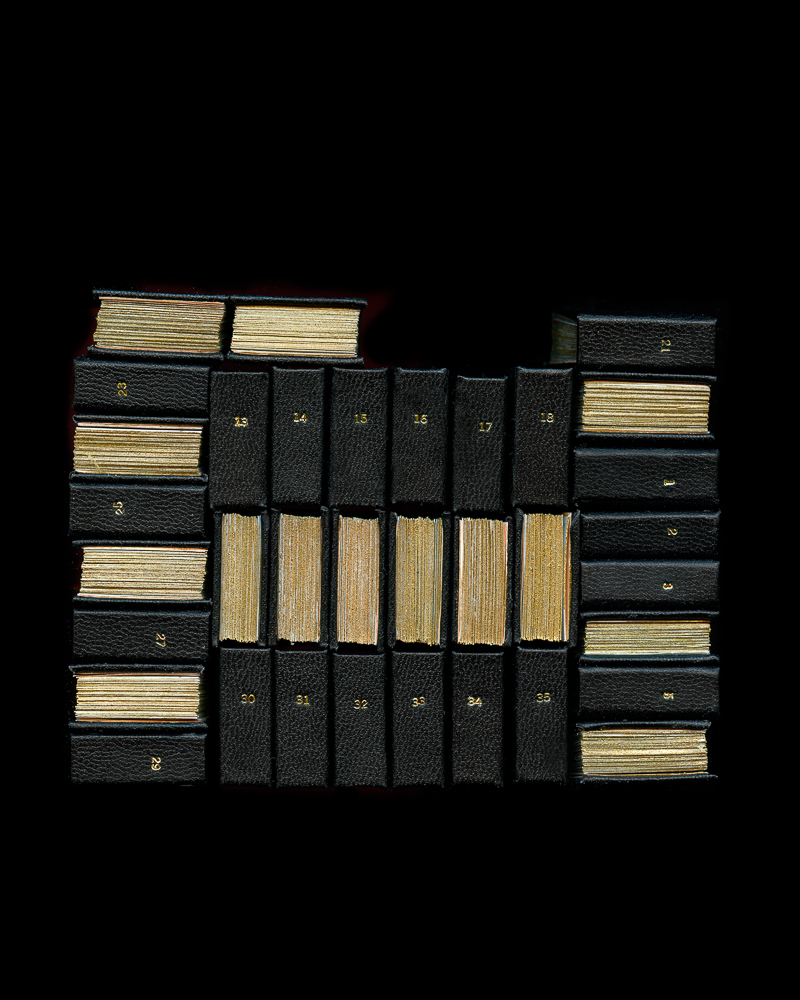

In 2012 I found a complete leather-bound set of the Encyclopedia Brittanica in mint condition in the landfill outside Aspen, CO. Unable to store 30 volumes, I rescued one book: #15, from P to R.

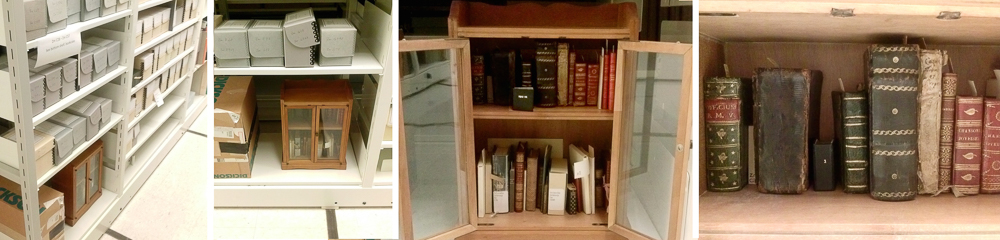

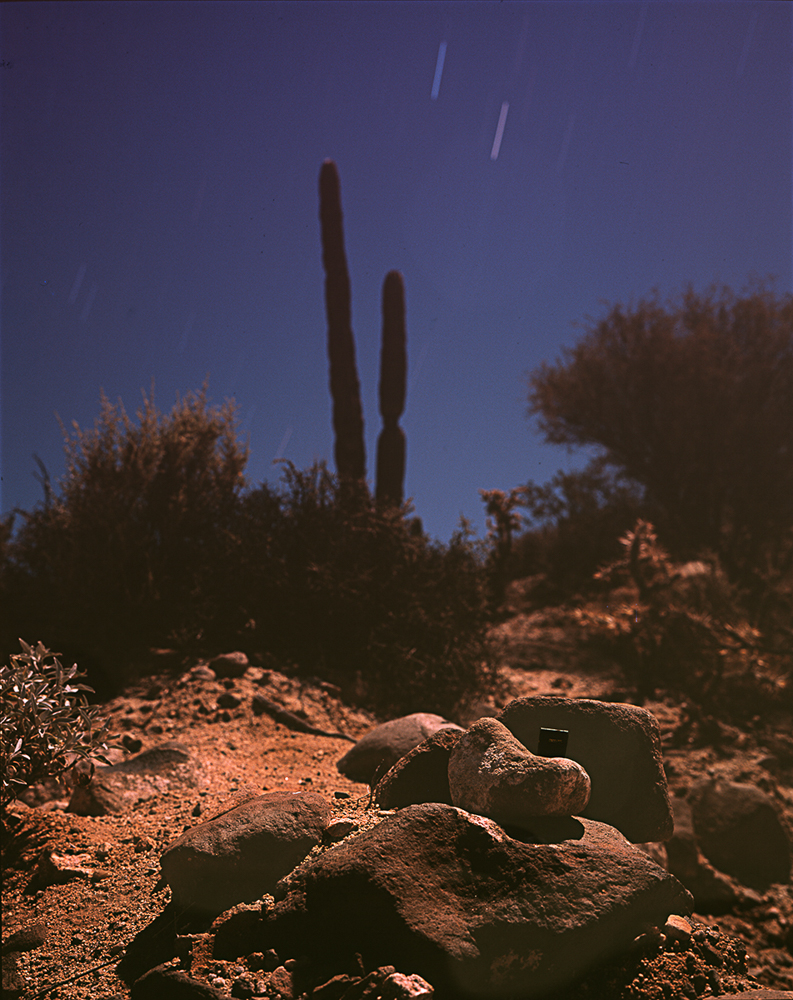

I photographed each page of the 1183 pages with a 35mm camera and printed the negatives in the darkroom. Each 35mm frame was bound into a miniature book yielding 35 continuous books. The text in each page is readable from beginning to end. The books were randomly distributed, the last known location documented in a photograph. To find the books and read the text requires effort. The finder must be aware of their environment and curious about what is inside to discover a small world of knowledge. The books reward curiosity and exploration – a surprise gift for the wondrous.

Tell us about your growing up and what brought you to photography?

I found photography as a teenager living in El Salvador. There was a powerful earthquake that destroyed much in the country, and it shut down my school for a month. My family lived there while my father was on assignment with the Food and Agriculture Organization, which is part of the United Nations. During my time off from school, I helped organize the local UN headquarters library. All the books had been knocked off the shelves and needed to be reorganized by catalog number. So doing this work, I found a yearly publication published by UNICEF called The Status of the World’s Children. Sebastião Salgado contributed his images to the report. Of course I had no idea who he was. All I saw was this one photograph of a young boy, maybe aged 5, standing in a giant landfill. The piles of garbage dwarfed him, but his expression was defiant, honorable, and courageous. I had never been moved by an image, or knew images were capable of provoking an emotional response. Being in a poor country destroyed by a natural disaster, that boy represented hope and evoked sympathy. When I discovered that both Salgado and the boy in the picture were Brazilian, I felt an immediate kinship. So in a way, I stumbled into photography, and I confess that I ripped that page with the picture and still have it in my studio.

Can you describe the photography community in Colorado?

In the front range, we have the Center for Fine Art Photography, the Colorado Photographic Arts Center, and Denver’s biennial Month of Photography, which are photo-specific venues that promote artists, events, and bring excellent programs to the area. Additionally, we have the Denver Art Museum, the Museum of Contemporary Art, and many galleries and independent spaces that often showcase photography through exhibitions and lectures. There are amazing artists working in the state. Financial support for artists and organizations, especially in light of Colorado’s high cost of living, is an important area of discussion to help make the community sustainable.

What defines a Colorado photographer?

Mountains at sunrise or sunset, bonus points for a blurred river or stream, and double bonus for some fall foliage and/or dramatic clouds. Use HDR and saturation at your own risk. Of course none of the artists featured in the States Project work like that. But I’m guilty of it too. I visited the Maroon Bells dozens of times, and never failed to make a picture. The landscape in Colorado is seductive. I’ll never stop making pictures of it.

We are sharing two vastly different projects today, can you tell us the process of how you find your subjects and your approaches to making work?

I think my work is instinctively reactive: I react to news, to the environment around me, to what I’m reading, and the work surges from all that. The project with miniature books came from finding an encyclopedia in the landfill and sitting with it and thinking about what to make with this beautiful object. Interference came from needing to find a way to process anxiety and information. In both instances, I reacted to external stimuli that occurred outside of my control.

Although my work can look vastly different, it translates the same conversation about power. In using candy as a subject matter for example, I’m interested in the power of consumption and desire. With the miniature books in From P to R, the act of giving away the product I made is a way to negate the power of consuming art, and instead of making art for art’s sake, and of having agency as an artist. In Interference, the consumption of news and the power of information/misinformation are key elements to the work.

What nurtures and sustains your practice?

When things are good, everything nurtures my practice: a walk, a book, an exhibition, a conversation with a friend. I spend a lot of time commuting between jobs, and I love podcasts that inform and engage my brain during that “down” time. Finding time to make work is my biggest challenge, and sometimes it feels like my practice is supported by a toothpick. Those are the times I really seek nurture from a community of makers, and find just one thing to make in the studio with no consequence, just to break the ice. With other artists working in different media, we formed a critique group that meets once a month for a studio visit. It’s informal but serious, friendly but rigorous. And sometimes I just watch Benedict Cumberbatch reading Sol LeWitt’s letter to Eva Hesse on repeat.

What’s next?

I’m really excited to show Interference in the Members Exhibition at the Center for Fine Art Photography in Fort Collins. I’m still working on the display and pretty excited to be taking a risk. The piece consists of 100 images, so it is a big task, but luckily I enjoy repetitive work!

And finally, describe your perfect day…

Any day spent traveling with my husband Evan, and our dog Dersu, in our 86 VW Vanagon is a perfect day.

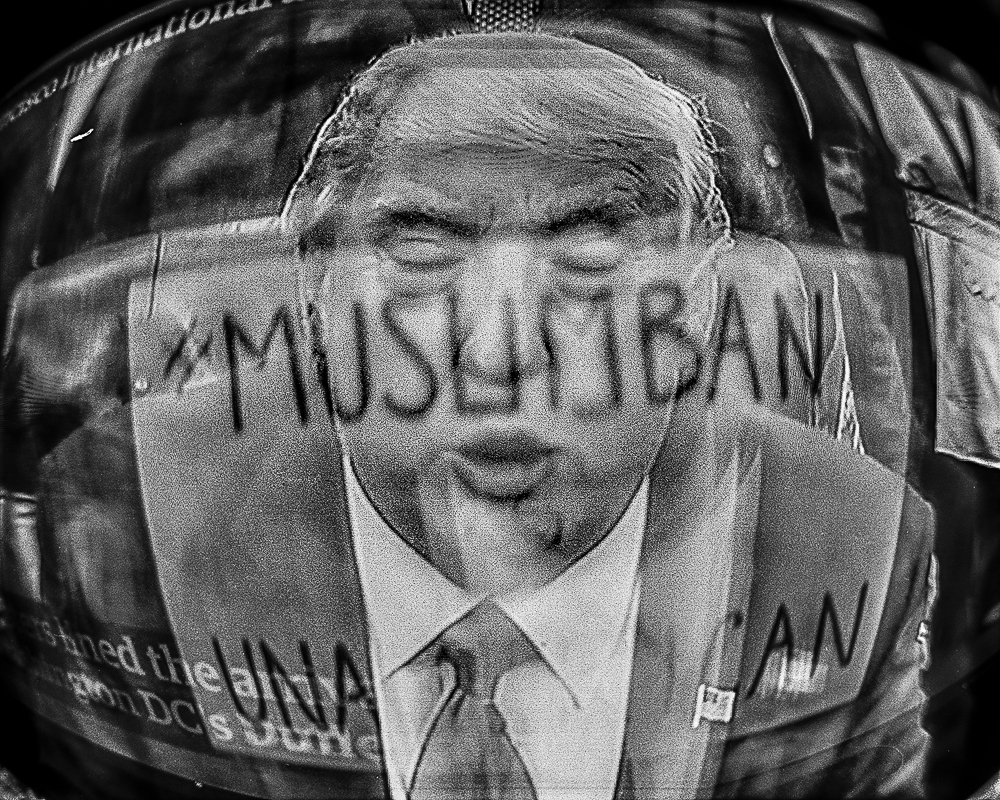

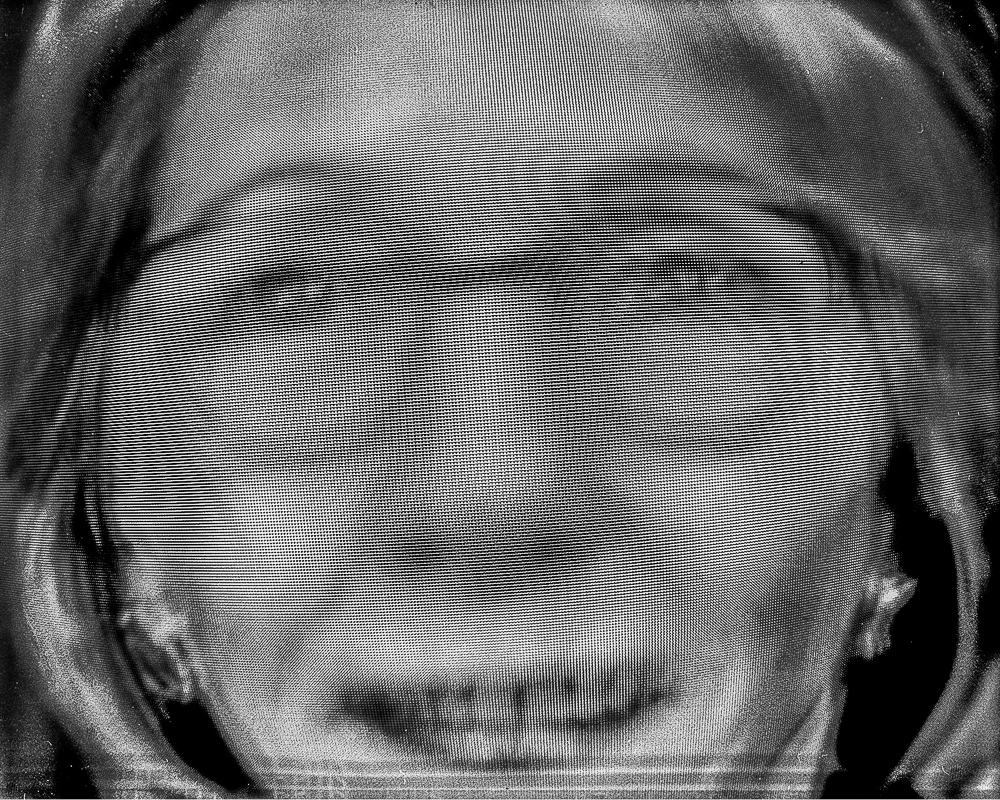

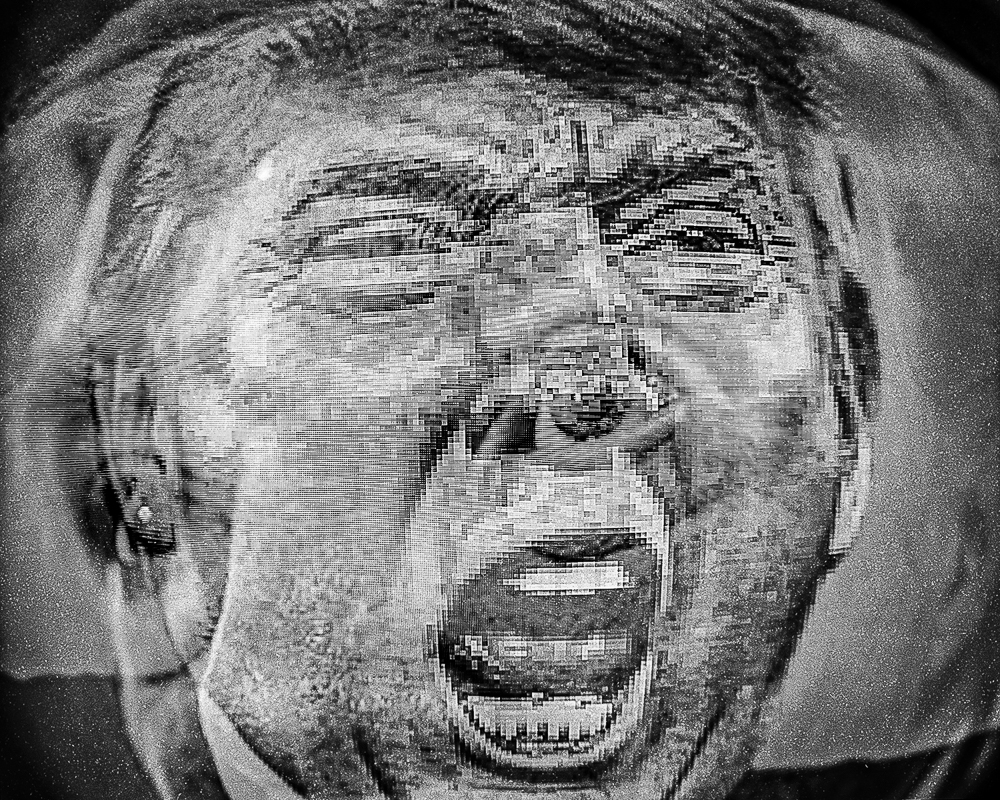

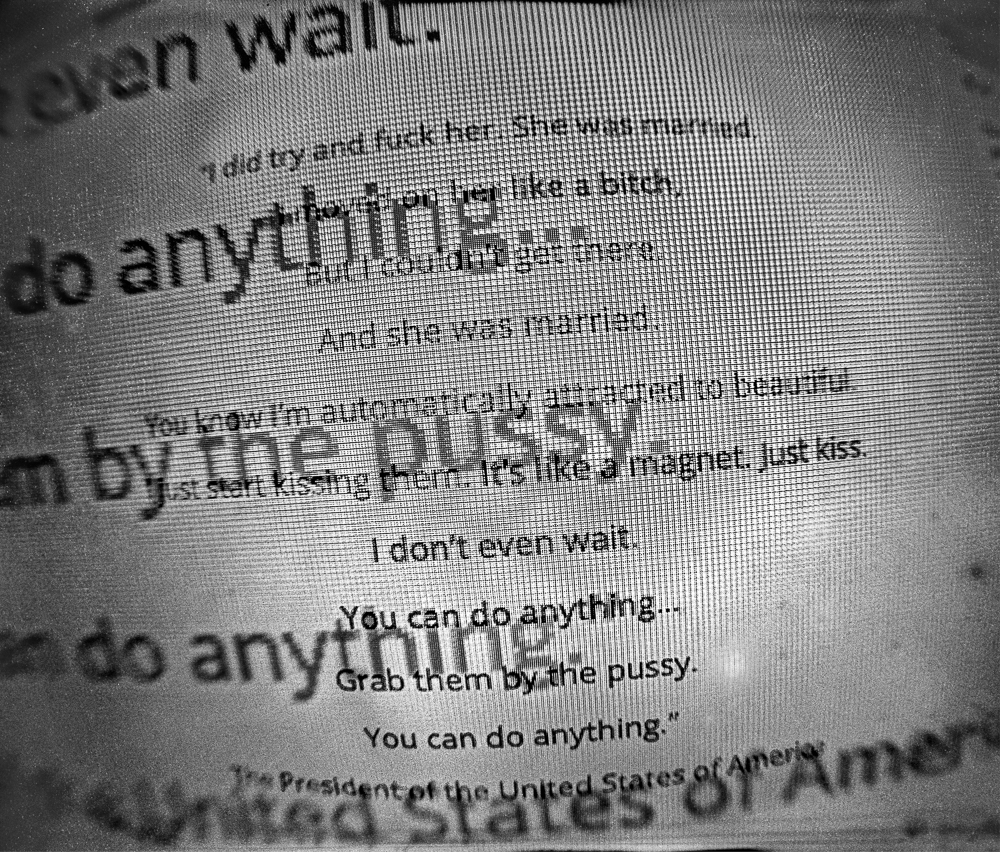

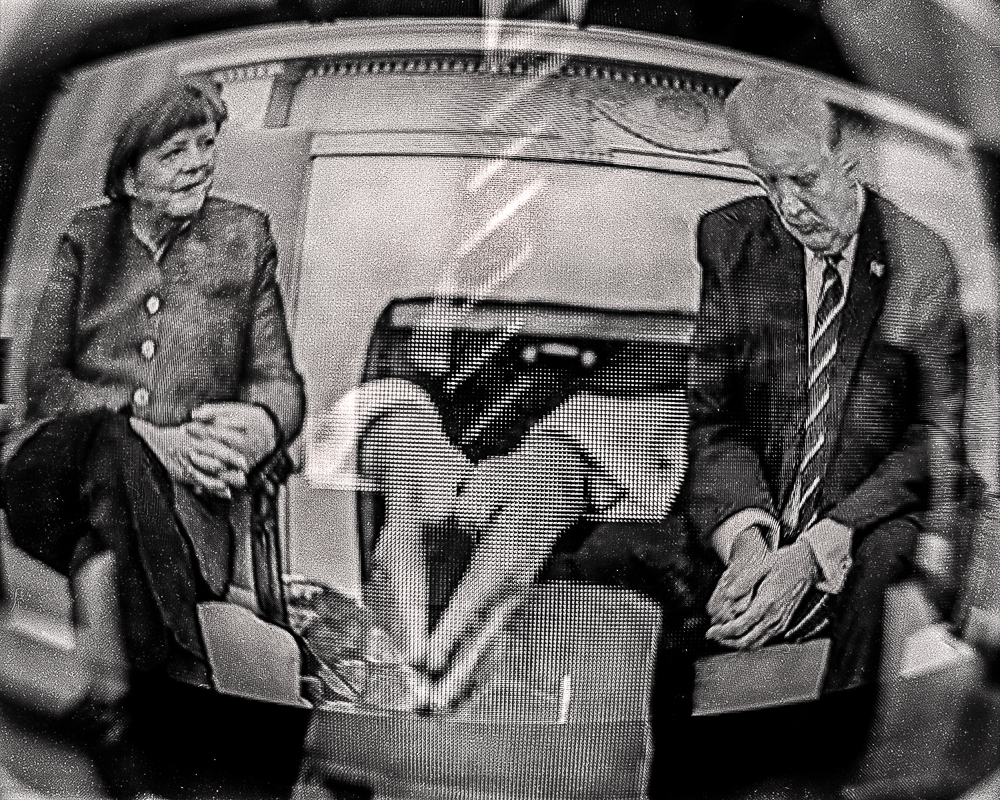

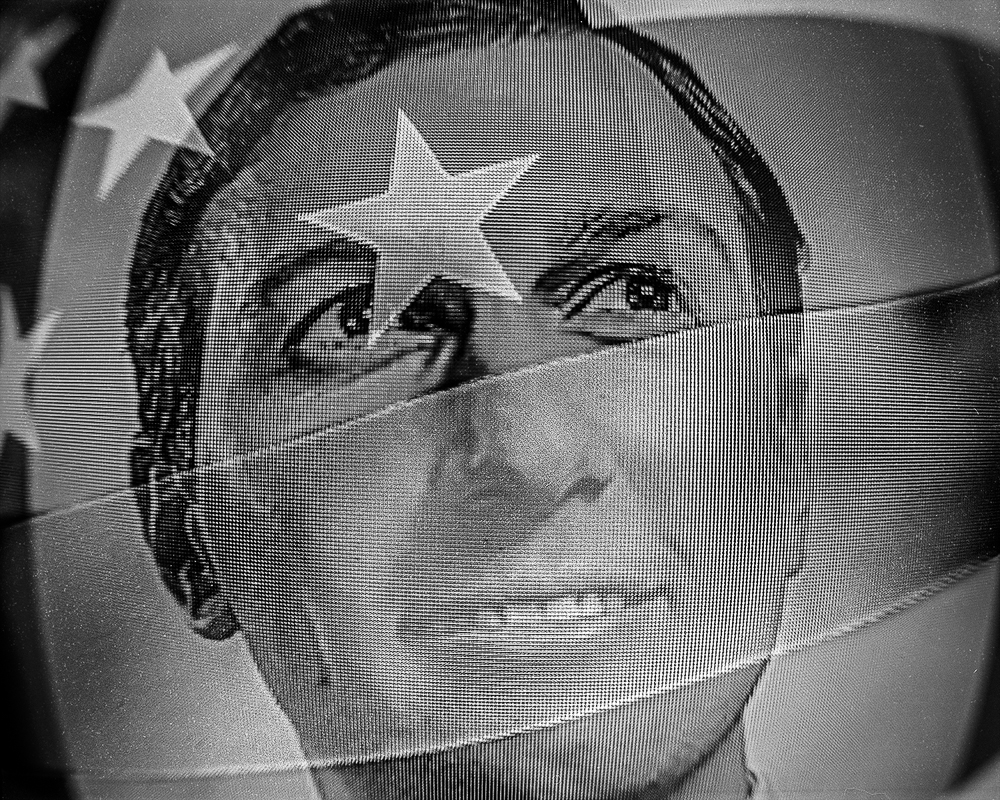

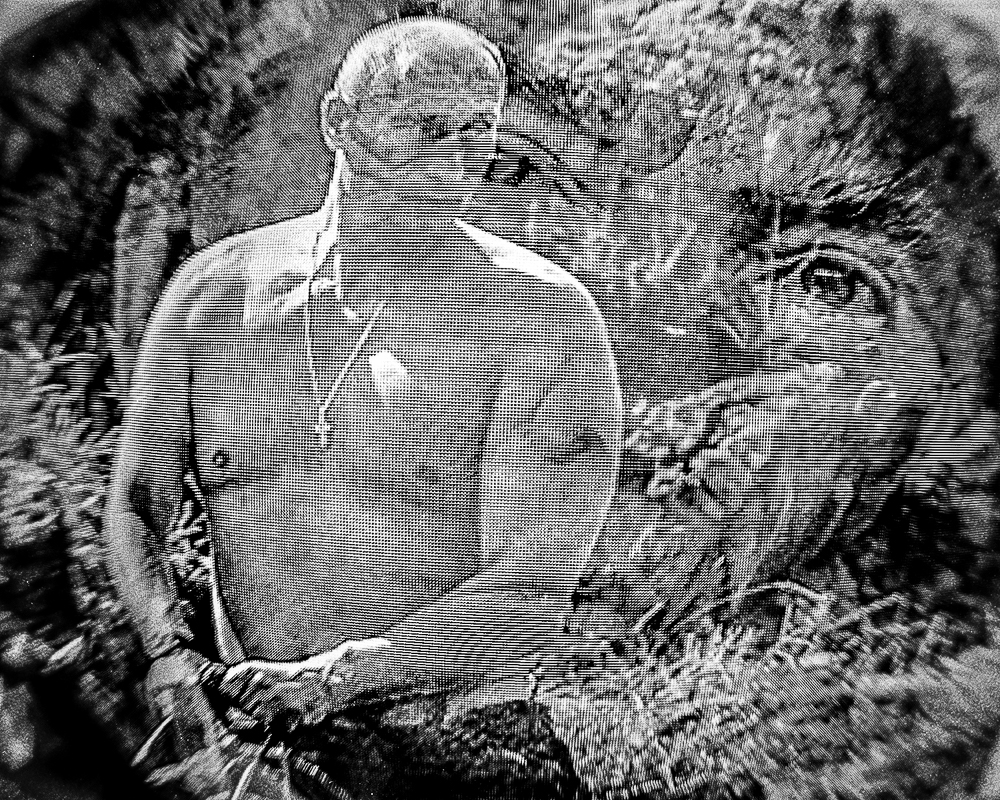

Interference

Interference documents the first 100 days of the administration of the 45th President of the United States through the medium of a television screen. The significance of the first 100 days of a presidency is debated, but historically has been used to gauge the future course of an administration. American exceptionalism has dominated the world stage for the last 70 years, backed by the world’s most advanced military. The course set by an American administration is closely watched in the global stage because its effects will ripple through every continent.

Photography has documented significant human events for almost two centuries, including scientific discoveries, distant galaxies, and human conflict. Photography is intrinsically linked to history, evidence, objectivity and truth – despite evidence to the contrary. How can photography be used to record events in the age of alternative facts and fake news?

In an effort to further abstract the news, a film camera with a distorting wide-angle lens recorded the daily news. The film was developed, scanned, and edited. The image metamorphoses from one medium into another – internet, tv screen, film, scanner, computer software. The technology interferes with each other, creating Moiré patterns: interference that appears when similar patterns are overlaid but slightly displaced. The images in Interference record distortions and unwanted artifacts that show the breakdown of information being translated through electronic devices. Each manipulation interferes with each other to distort any original meaning and confuse a final resolution.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Laura Shill: The States Project: ColoradoDecember 24th, 2017

-

Abbey Hepner: The States Project: ColoradoDecember 23rd, 2017

-

Teri Fullerton: The States Project: ColoradoDecember 22nd, 2017

-

Heather Oelklaus: The States Project: ColoradoDecember 21st, 2017

-

Ashlae Shepler: The States Project: ColoradoDecember 20th, 2017