South Africa Week: Thandiwe Msebenzi

Two themes animate the work of Thandiwe Msebenzi: silence and the performance of gender in South Africa. Msebenzi’s two major bodies of work explore these themes through different subjects — the clothing worn by Xhosa men following initiation ceremonies and the ways women encounter and are normalized to patriarchy at home. Much of her work, she says, has “been about me trying to understand masculinity, me seeing myself in masculinity, me being the observer of masculinity, me being affected by masculinity.” Despite the gravity of her questions, a sense of quietude pervades Msebenzi’s photographs. Her photographs use a soft palette and natural lighting to create visual metaphors through dress that probe at issues of gender performance.

Msebenzi’s most recent series, Awundiboni – You Don’t See Me looks at ways patriarchal systems are normalized at home. The project grew in direct response to an incident in which she was harassed by a man while waiting for a bus in Cape Town. “This happened to me and has happened to many other women before,” she says, “and I wanted to speak about it.” Her series looks at collective silence — and tacit acceptance — surrounding such public violations against women’s bodies and how that silence is fostered first at home. “At home you’re told you cannot talk about your uncle in this way, you cannot talk about your father in this way. Before you even leave the outside world, you’re really silenced within your home.”

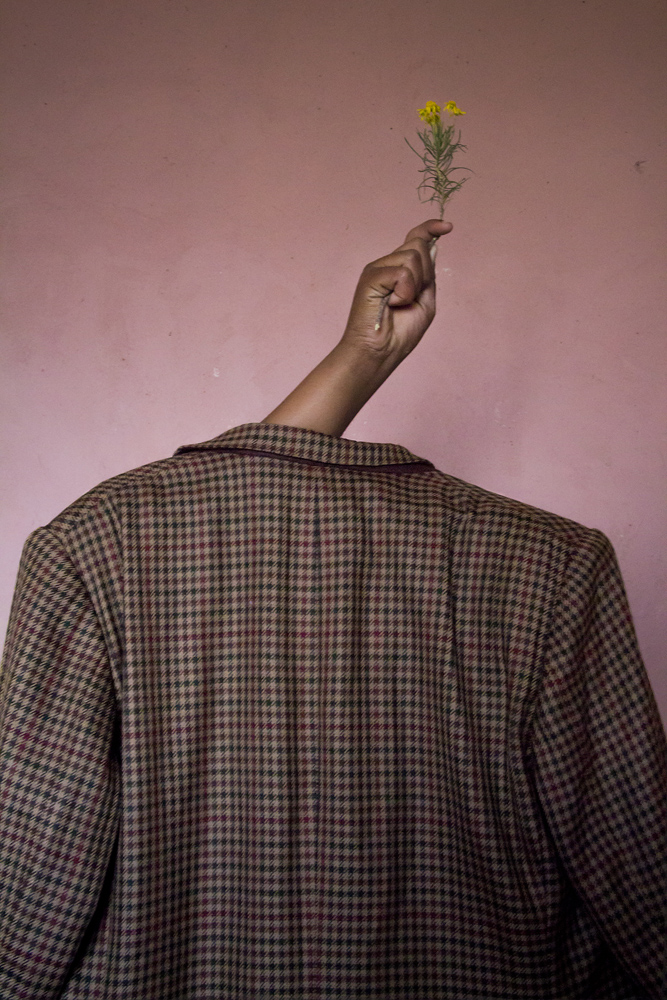

The collection of still lives, tableus, and self-portraits in the series quietly probe at the subtle ways women become normalized to a system of power that excludes and limits their voice. In images such as “Indawo yam” and “Ndivumele ndimemeze” Msebenzi covers her face and body with lace and embroidered cloth. By obscuring her identity and form she looks at how females can be physically present in a space but unable to speak about the issues affecting them. In other images, Msebenzi confronts a pervasive male gaze that preys on women — even at home. In “ she peers back through a window from the outside at an unseen observer: “I say what are you looking at — questioning the person that’s looking at me.”

The photographs in Awundiboni – You Don’t See Me form part of Msebenzi’s ongoing efforts to generate a visual narrative that challenges gendered representations of women. As an artist, Msebenzi is inspired by the work of Zanele Muholi, whose work she first encountered as a student. She remembers learning that Muholi — in Faces and Phases — wanted to create a body of work about the LGBTQI community that could reproduce and decolonize a narrative that was written by people who were outside of that culture. Muholi’s objective offered Msebenzi’s a new way to think about photography and her power as an image maker. Since that time she’s tried to use her photography to develop a new narrative about her own experience as a black South African. The challenge, for Msebenzi is to think about how to “rewrite a narrative that’s been so broken…how do we rewrite a culture or a history of people that have been dehumanized and have been criminalized throughout the history of photography?”

Each image in “Awundiboni” relates to Msbenzi’s personal experience or that of her family. A delicate arrangement of sticks and sharp objects against a blue bed cloth shows items women in her family keep ready to protect from male intruders. “uMakazi-Ndi mamele (Aunt, speak, I’m listening)” looks back to Msebenzi’s first experiments with observing and performing femininity. Msebenzi says that creating the series not only allowed her to confront a pervasive issue, but it created an opportunity for her to work through her own frustrations. As visual artists, Msebenzi says, “we’re able to make work about pain, but we make that pain beautiful. I think that’s what heals us. It’s the beauty that comes out of our pain and from that we heal.”

Thandiwe Msebenzi a artist born in 1991 in Nyanga, Cape Town. She studied Fine Art at Michaelis School of Fine Art at the University of Cape Town and earned BA in 2014. Msebenzi was awarded a Tierney fellowship that same year and since then has exhibited widely across South Africa. In 2016 she completed a residency at the Cape Town School of Photography. Having experienced first hand the Fees Must Fall protests, in 2017 she also joined the iQhiya collective of 11 black female South African artists exhibiting together at Cape Town’s AVA Gallery.

In 2015 she took part in THAT ART FAIR, Kasi2Kasi Art Expo in Gugulethu, the Returning to the Sender exhibition held at the CAS Gallery, and Turbine Art Fair under the emerging artist project Fresh Produce. In 2015 Msebenzi became part of IQhiya collective taking part in AVA IQhiya solo show, FNB Joburg Art Fair. In 2016 she was an ABSA L’Atelier Top Ten, participated in a group show By Way of Hand photography exhibition held at Cape Town School of Photography. She also completed a four months residency at the Cape Town School of Photography in 2016.

©Thandiwe Msebenzi, ToolsBlueSheet “Phansti kwe bhedi ka Ggogo”, 2016, German etching archival paper

Awundiboni- You Don’t See Me

This work tells the story of sexual violence against women through a personal prism. It finds its origins in my childhood memories of witnessing violations that always seemed obscured behind curtains. I grew up in a community where old men lurked in the streets looking for younger women to harass and violate. And as I became a young woman myself, I was constantly reminded that my body, and those of other young women, did not belong to us but were rather available for consumption by the eyes and hands surrounding us. The project was triggered when I experienced physical sexual harassment in a public setting. This got me thinking about how women’s bodies are interpreted in these spaces. And, through my daily witnessing and experiences, this body of work was born.

As I delved into this project, my work started to reflect not just public spaces, but increasingly private ones too, especially the home. The home is a space of safety and comfort, but for many women it can also be a space where we feel most vulnerable, afraid and silenced. I feel like the home is still a space that we view as private and so don’t sufficiently interrogate. In this way, it can become a shrouded space saturated by secrecy and violations in the shadows. Our bedrooms, for example, should offer us privacy and relaxation, but these spaces can also be sites of trauma and pain. Indeed, while you are sleeping you are arguably at your most vulnerable. This tension of trauma and comfort represented by the home, and specifically the bedroom, kept resurfacing for me during this project. For example, when I realised that my grandmother sleeps with weapons under her bed for protection in case she is attacked at night. My mother does the same. Will I too have to sleep with an arsenal under my bed one day?

As much as this project is driven by women’s fear of sexual violence in both public and private spaces, this work is also a celebration of resistance. It seeks to capture both the women’s pain and trauma, but also their immense strength in the face of the sexual violence epidemic that continues to grip South Africa. – Thandiwe Msebenzi

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Week: Aaron Huey: Wallpaper for the End of the WorldApril 26th, 2024

-

Earth Week: Casey Lance Brown: KudzillaApril 25th, 2024

-

Tara Sellios: Ask Now the BeastsApril 6th, 2024

-

ALEXIS MARTINO: The Collapsing Panorama April 4th, 2024

-

Emilio Rojas: On Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands: The New MestizaMarch 30th, 2024