Southbound: Photographs of and about the New South

It is such a pleasure to introduce Southbound: Photographs of and about the New South. Over the next week, we will feature selections of images from each of the 56 artists included in the project, as well as accompanying essays, maps, and videos. This expansive, comprehensive, multimedia investigation into what it means to be of, from, by the American South in the first decades of the twenty-first century was co-curated by Mark Sloan director and chief curator of the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art, and Mark Long, professor of political science, both of whom are on the faculty of the College of Charleston, in South Carolina.

According to Mark Sloan and Mark Long, “Southbound embraces the conundrum of its name. To be southbound is to journey to a place in flux, radically transformed over recent decades, yet also to the place where the past resonates most insistently in the United States. To be southbound is also to confront the weight of preconceived notions about this place, thick with stereotypes, encoded in the artistic, literary, and media records. Southbound engages with and unsettles assumed narratives about this contested region by providing fresh perspectives for understanding the complex admixture of history, geography, and culture that constitutes today’s New South.”

In their multidisciplinary approach, the curators honor the complexity of the region and the many different perspectives that constitute the Southern identity. The project comprises fifty-six photographers’ visions of the South, complemented by a commissioned video, a digital mapping environment, extensive public programming, a two-hour Mixcloud playlist, an all-encompassing stand-alone website, and a comprehensive exhibition catalogue. A fuller picture of the project’s components and the associated events is available on the project website here. Southbound was recently exhibited in its entirety at the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Photography and the City Gallery in Charleston, and plans to travel to various locations across the South, first to Gregg Museum of Art & Design, NC State University + Power Plant Gallery, Duke University from September 5 – December 29, 2019, with other exhibitions planned into 2021.

The Rooster, 2013 Brown Fork, Kentucky © Shelby Lee Adams

Ally,PawPaw, Madison County, North Carolina, 2012 From the Staring series. PawPaw, Madison County, North Carolina © Rob Amberg

At Cricket’s Birthday Party, Big Pine, Madison County, North Carolina,201. From the Little Worlds series. Big Pine, Madison County, North Carolina ©Rob Amberg

Seeing the New South – Mark Sloan and Mark Long

Representing the largest exhibition of photographs of and about the American South in the twenty-first century, Southbound: Photographs of and about the New South presents multiple ways of visualizing the region. All are necessarily incomplete and imperfect, yet viewing the region through different lenses may bring into focus, however fleetingly, this newest New South. Representations of the world around us in the languages of fine arts and geography, embodied for Southbound in photography and digital mapping, are central to how we see our world.

The exhibition’s curators, one a museum director, curator, and photographer from the South, the other a transnational geographer and professor of political science, find common ground around the salience of place in the human condition. For all our fascination with our parallel digital existence, we are embedded in the world around us, dependent on it for our material and, for many, spiritual needs. A sense of place results, and the purpose of the selection and organization of the component pieces of Southbound is to explore this place we call the South.

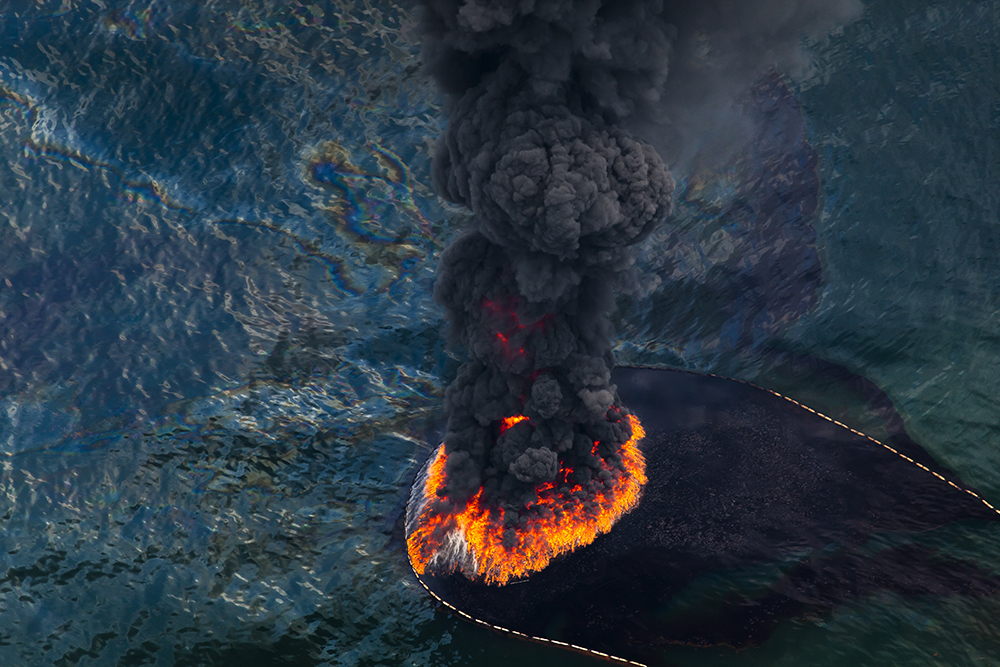

Oil Spill #4, 2010. From the Spill series, Gulf of Mexico © Daniel Beltrá

Nearly everywhere has a South, even though at the city scale we often talk about the Southside. South is, of course, a cardinal place. Perhaps nowhere is this more the case than in the United States, where the economics of slavery inscribed notions of a South writ large onto a national map that it would have rent asunder. That moment in history and its echoes in the region, which are carefully charted by the Southbound photographers, serve as a foil against which to burnish all that the United States purportedly represents. The South abides, in part, to incarnate shortcomings common across the country.[i] When read against that reductionist grain, however, the region emerges in all its complexity, certainly as pictured over recent decades.

[i] David R. Jansson, “Internal orientalism in America: W. J. Cash’s The Mind of the South and the spatial construction of American national identity,” Political Geography 22, no. 3 (March 2003), 293–316.

In making the selections for Southbound, our basic criterion was that an artist had to have had some sort of sustained engagement with a Southern subject (or multiple subjects) over time, since the year 2000. Rather than casual travel or “drive-by” images, we were searching for a deeper involvement. For us the artists’ quests were as interesting as their imagery. We restricted ourselves to the universe of existing photographs made by artists working in the region and did not commission new work. At the mercy of the faces, places, and practices that interested the photographers, there were coveted images we never did find.

Geraldine at the Sharp Family Reunion in Pickett State Park, 2014. From the Silent Ballad series, Jamestown, Tennessee © Rachel Boillot

Overlaps and duplications across the work of photographers making pictures in the South made for difficult decisions. In the social-scientific tradition that was central to our efforts, we did much counting: of images depicting rural poverty, for example, to ensure that, powerful as any particular photographs might be, they would not weight the exhibition too heavily. Likewise, we were anxious to ensure that the influx of Hispanic and Latino populations to this New South would be reflected in the images chosen. Always, we were tallying—the number of photographers and who they were: women and men, artists of color, LGBTQ+ photographers, established and emerging artists; how many prints, and what they showed: landscapes and portraits, rural, urban, and suburban scenes; demographics such as race, age, and class; workplaces, pastimes, topographies, seasons, and a long etcetera. We constantly queried our selections: “Do we have enough photographs that speak to religion and religious diversity in the region? Are two photographs with tire swings one too many? Does our choice of images show that black lives matter?” All of these considerations were entered into our selection calculus, to be counted and balanced in turn. What emerges is one slice of a New South in transition, sufficiently complex, we trust, to capture something essential about the region in the early twenty-first century.

Max with Papaya, 2011. From the Bittersweet on Bostwick Lane series, Richmond, Virginia © Susan Worsham

Light Through Embalming Fluid, 2015. From the Bittersweet on Bostwick Lane series, Richmond, Virginia © Susan Worsham

Eno River, 2004. From the New Wilderness series, Durham, North Carolina © Jeff Whetstone

For all its ranging ambition and scope, Southbound is not intended as a comprehensive survey, an impossible task in a region as vast, dynamic, storied, and charged as the South. Instead, it reaffirms that today’s New South, subject to invention, construction, and interpretation (like all places), is the latest iteration of a place that resonates with populations near and far. Further, we understand that documentary and fine art photographers making images in the South are revealing of life in the region, the more so for the aggregate picture that emerges in a project such as Southbound. Always, any one image, individual or composite, coheres somewhere in the space between the objects pictured, the artists’ looking, and our own, and so there can never be but approximations of the fascinating place that is the American South.

Southbound, then, is one such approximation, guided, in part, by our curatorial goal of revisiting, rethinking, and expanding on the photographic iconography of the region, synonymous, for many, with Walker Evans’s Depression-era photographs, which have become emblematic of the poverty there.[i] Those images, and a few others from the Farm Security Administration era, act as a kind of shorthand for the deprivations the South has endured. Another set of damning images from the middle of the twentieth century, made by Gordon Parks and others, serve as signposts for white intolerance, in both dramatic and workaday settings.[ii] For all that they showcase the quiet dignity and indomitable determination of African Americans to triumph over injustice, those photographs evoke a benighted South.

Southbound is designed, in part, to move beyond such archetypal images of the region. To that end we were drawn to photographs that lent themselves to dialogue with—even to recasting or rebuffing—taken-for-granted understandings of the South, as well as to images that illuminate new facets of life there. Inevitably incomplete, Southbound presents a new vision of the New South in the new millennium through the eyes and minds of photographers working in the region.

[i] James Agee and Walker Evans, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1941).

[ii] Gordon Parks, Segregation Story (Göttingen: Steidl, 2015).

Jungle Slide, 2013. From the Beyond the Plantations: Images of the New South series, Mount Pleasant, South Carolina © Michelle Van Parys

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Paccarik Orue: El MuquiDecember 9th, 2025

-

Lauri Gaffin: Moving Still: A Cinematic Life Frame-by-FrameDecember 4th, 2025

-

Dani Tranchesi: Ordinary MiraclesNovember 30th, 2025

-

Art of Documentary Photography: Elliot RossOctober 30th, 2025

-

The Art of Documentary Photography: Carol GuzyOctober 29th, 2025