The Brian Taylor Mixtape

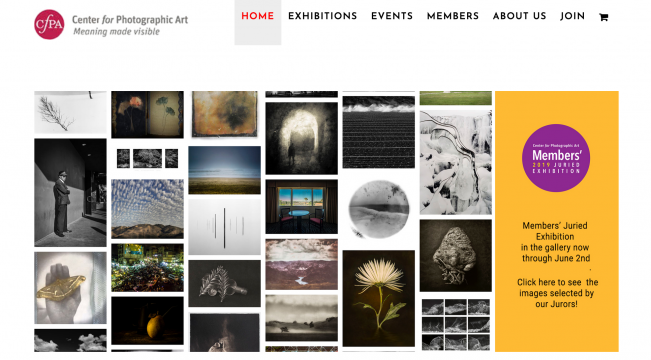

I remember the first time the name Brian Taylor came on my radar. It was an e-mail from someone I didn’t know in 2016–that someone was the Director of the Center for Photographic Art in Carmel, CA, inviting me to teach during their PIE Workshops. It was unlike any e-mail I had received in a business sense–warm, engaging, and very complimentary–it as if this stranger was reaching through the internet to give me a big hug, welcoming me into his world. Meeting Brian months later, he mirrored his e-mail exactly, welcoming me with a shit eating grin, joy, inclusiveness, and yes, a hug. Brian is truly one in a million and I feel so lucky to have circled around his orbit these past few years.

This Mixtape has unique timing as Brian has just stepped down from his Directorship and handed the reigns to the very capable Ann Jastrab, the former Director of the Rayko Photo Center in San Francisco.

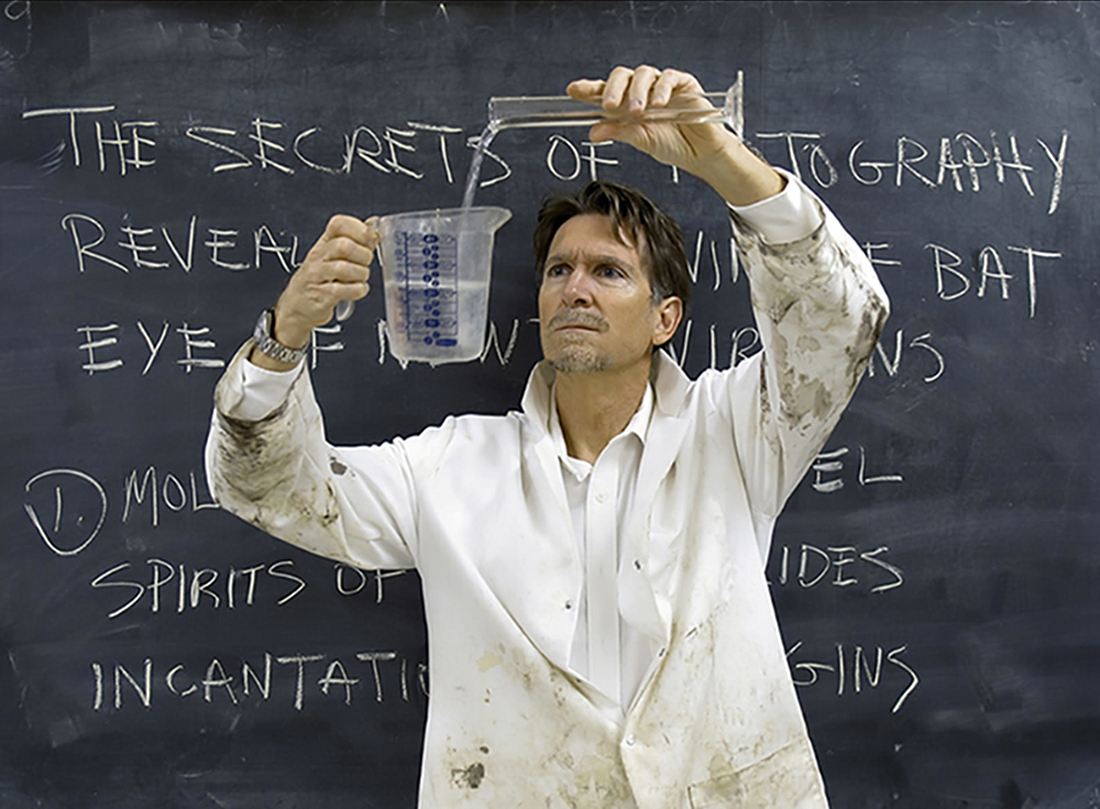

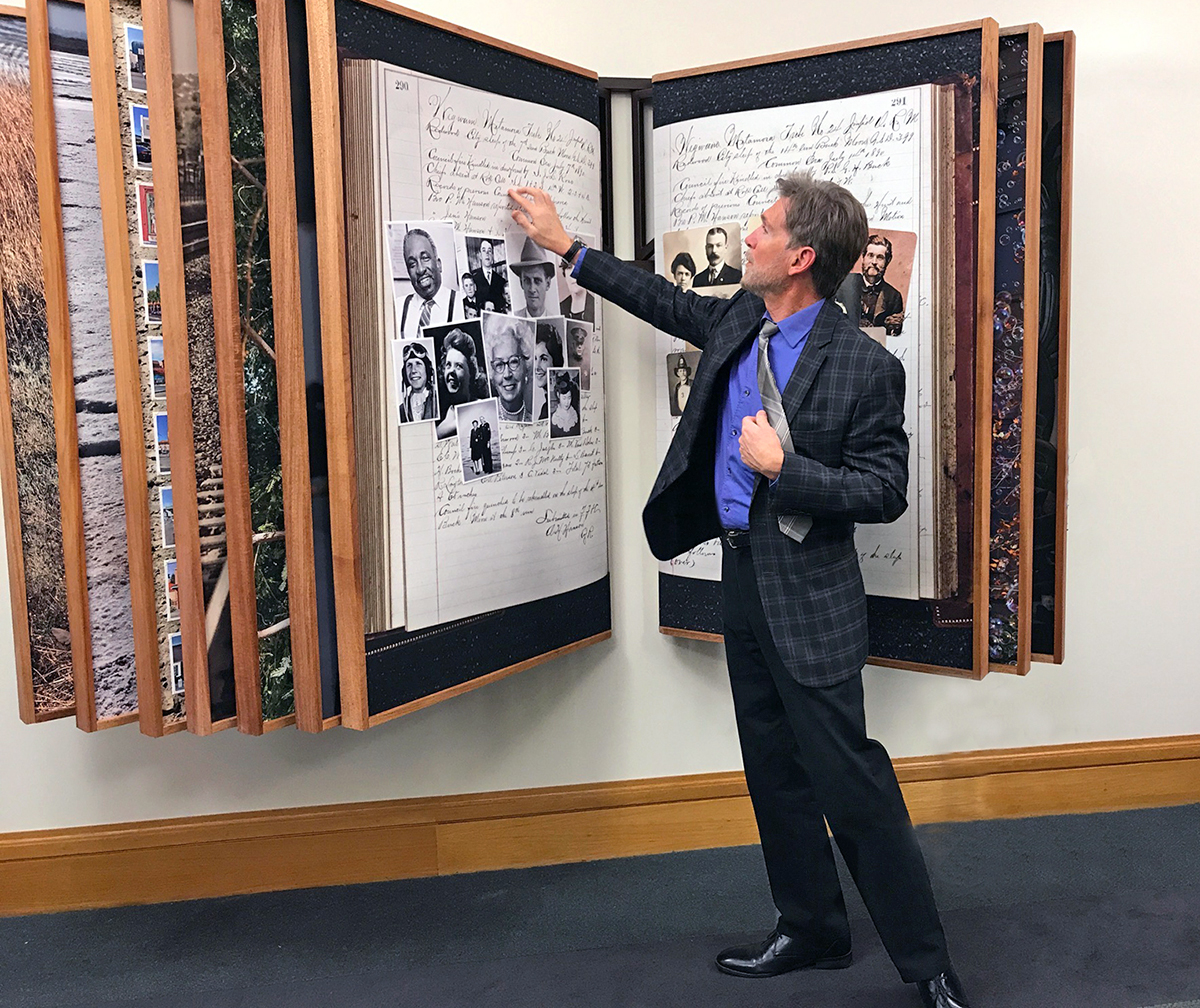

So I am using this post to share the story of this remarkable person, on a day which happens to be his birthday (Happy Birthday Brian!). After 40 years of giving to the photographic community as an educator and director, he is turning his focus back on to his own work and I couldn’t be happier for him. Brian is known for his innovative explorations of alternative photographic processes including historic 19th Century printing techniques, mixed media, and hand made books. He received his B.A. Degree in Visual Arts from the University of California at San Diego, an M.A. from Stanford University, and his M.F.A. from the University of New Mexico and served as a professor of Photography for over 30 years, and Chair of the Department of Art and Art History at San Jose State University. His work has been exhibited nationally and abroad in numerous solo and group shows and is included in the permanent collections of the Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris; the Victoria and Albert Museum, London; the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; and the International Museum of Photography at the George Eastman House, Rochester, NY.

Raising a toast to my friend and so happy to share The Brian Taylor Mixtape!

Tell us about your growing up and what brought you to photography.

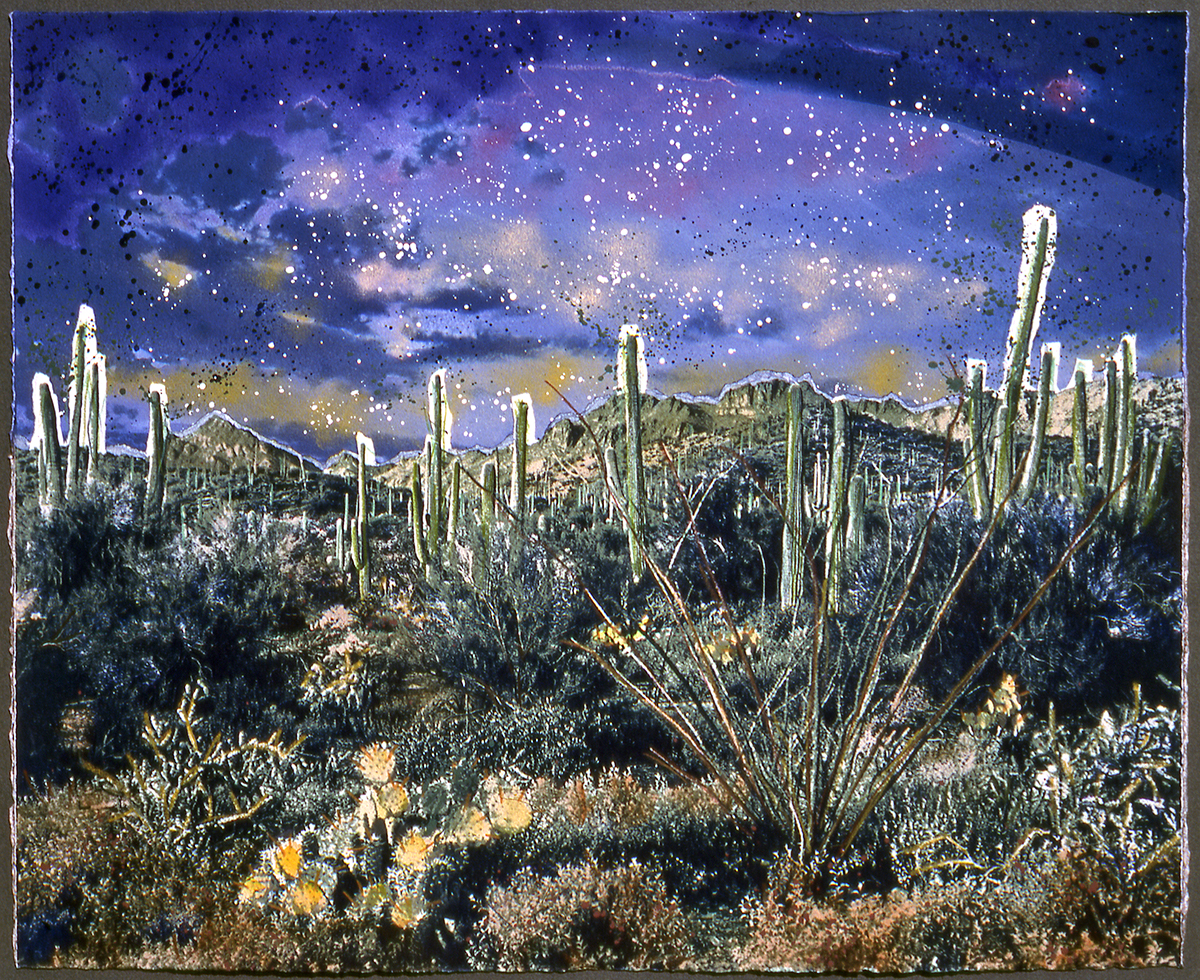

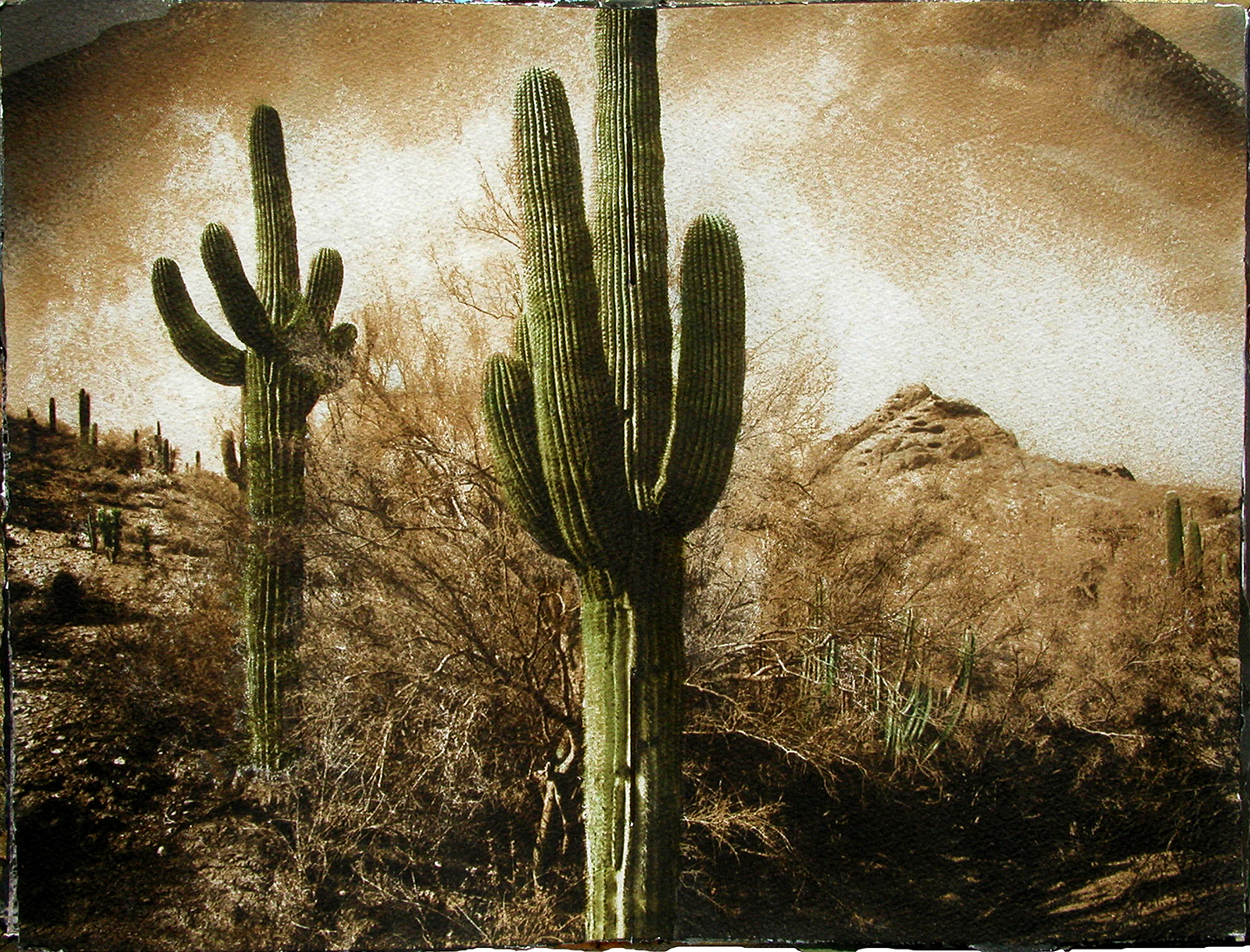

I was born in Tucson, Arizona, the land of Carlos Castaneda’s magical encounters with mystical desert shamans and talking coyotes. Spend any night alone in the enchanted and precarious Sonora Desert* and you’ll experience a glimpse of the surreal, dreamlike realities that inspired my attraction to voodoo alternative photo processes.

*Castaneda’s peyote optional

I believe that a work of art created by a human touch may contain a resonance of that touch, a lingering aura. My aesthetic has changed through the years, but my fascination with traces of the human hand has always remained. I’m drawn to photographic techniques that allow imperfections and texture, so I’m attracted to the unpredictable “gifts” of alternative processes and the ragged edges of handmade books. In this digital age of pixels and printers, many photographers still savor making art the hard way— by hand. For us, life’s usual heartbreaks, tragedies and bitter disappointments just aren’t enough!

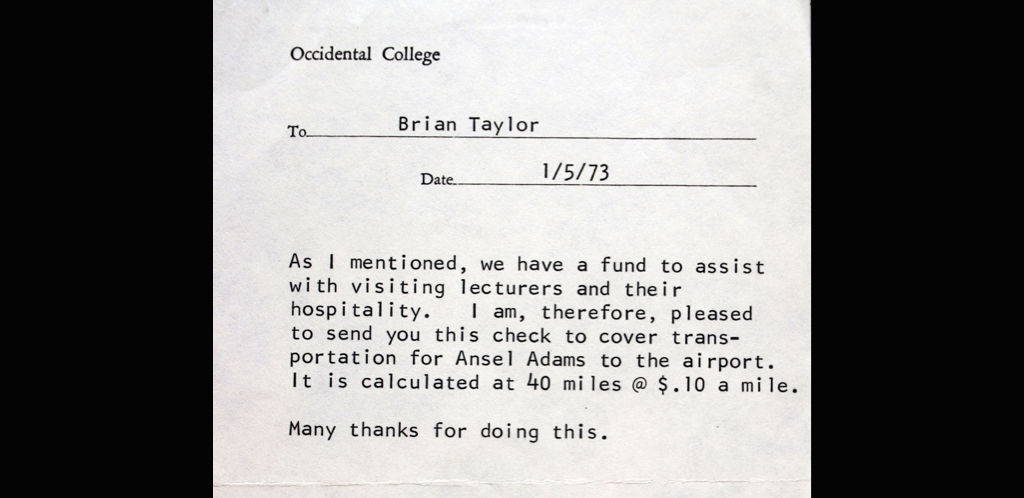

I fell in love with photography in high school and this early discovery helped me cover a lot of ground during my youth. In those days, every mother wanted her son to grow up to be a doctor or a lawyer— anything but a fine art photographer! I enrolled in Occidental College as a pre-med student, yet soon realized I wanted to dedicate myself to a life in the arts. Even as a freshman science major, my teachers could see that I was a young photo piranha, so when Ansel Adams was brought to campus for an honorary Doctorate degree celebrating his environmental activism, they invited me to be his guide. Eventually, I had Ansel trapped in my car for the hour long drive across LA to the airport and I spent the time relentlessly telling him all about his own life. (I always thought it was odd that he flung himself out of my moving car the minute we arrived at the airport…)

When I was 18, I was incredibly fortunate to find an inspiring role model and world class mentor in Oliver Gagliani— a classical purist and straight photographer extraordinaire, deeply committed to his art. Every summer during the next four years, I would speed straight toward the old silver mining town of Virginia City, Nevada and remain immersed in Oliver’s workshops where I ate, slept and breathed the Zone System. I couldn’t get enough– I’d eagerly volunteer to process Oliver’s long, N+7 film development tests for two or three hours in total darkness in an eerie, makeshift darkroom in the basement of the 150 year old former Saint Mary’s Hospital. The dusty brick building had a well-documented ghost, the White Nun, who would faintly, timidly visit me in the darkroom around the 3rd hour of developing sheet film in the dark!

Oliver was in his sixties when I first met him, but he was always the first person up in the morning, leaving before sunrise to capture the early morning light. After each workshop ended, Oliver and I would set sail in my van and tour the back roads and ghost towns of Nevada. Even though my aesthetic eventually diverged from his, I’m absolutely beholden to Oliver for instilling in me a such a strict sense of self-discipline and a classical upbringing in straight photography. Oliver was an accomplished violinist, his friends Ansel Adams and Paul Caponigro were pianists, and Wynn Bullock was an opera singer, so it made perfect sense when he reminded me, “Every musician must learn to play their instrument before they compose their own piece.” These were rare and everlasting experiences during the formative years of my art.

I received my BA degree in Visual Art from UC San Diego and realized that, if one had to work, teaching was the best job in the world for an artist. So I went off to Stanford for an MA in Education and was then fortunate to be accepted into the MFA program at the University of New Mexico during its heyday. Those were grand times at UNM when it was a world class dynasty of photo education created by Van Deren Coke (having just been Director of the George Eastman House), as well as Beaumont Newhall (founder of MOMA’s Photography Department years earlier). Imagine sitting in a small classroom with Beaumont Newhall and a dozen other lucky grad students, hanging on

Beaumont’s every word as he recounted his days with dear friends like Alfred Stieglitz and Cartier Bresson, or sitting by the Carmel River with his pals Ansel Adams and Edward Weston!

The graduate photography program at UNM was intimidating and avant-garde at the time; I shared a darkroom with Joel Peter Witkin and other illustrious grad students. Professor Tom Barrow was scratching his negatives, which was unthinkable in traditional photography. I adored Betty Hahn, the professor whom Coke recruited to offer an organic, handmade, photographic aesthetic. Betty toppled my stiff Jenga Tower of the Zone System and redirected my approach towards a freer, more-liberated, anything-goes attitude. As much as I respected Oliver’s technique, it wasn’t my voice. I was younger than he and sassier, I needed a medium that was more liberating; I wanted to say different things. I took the science and predictability of the Zone System and applied it to the much more unpredictable, malleable world of non-silver processes.

When I graduated from UNM with my MFA, I returned to California at the age of 24 and began my teaching career at California State University San Jose, where I taught photography for almost 40 years and ended up as Chair of the Department of Art and Art History.

What is your title and job description and tell us about a typical day?

With fond memories of my time as a professor, I removed my academic cap five years ago and put on my nonprofit hat, currently as the Executive Director of the Center for Photographic Art in Carmel, California’— the Land of f/64. Tracing our roots back to the Friends of Photography founded by Ansel Adams, Cole Weston and other West Coast luminaries in 1967, our gallery remains the second oldest member photographer gallery space in America. (Nobody likes to come in second, but Alfred Stieglitz’s Camera Club of New York, founded in 1884 is still active).

A typical day in the gallery is filled with the joys and sorrows of being in a position of power in today’s art world. It’s always a delight to deliver good news and say Yes! to the hopes of an aspiring artist. And of course the job also entails being the messenger of sad tidings when we can’t offer an opportunity to those many talented artists who are always inquiring.

It’s never a dull moment running a nonprofit— from balancing a budget to balancing on a ladder. Some days I put on my Curator’s hat and work on an essay for an upcoming exhibition. Other days I stare at a grant proposal, or have my Fundraiser’s hat in hand and take a generous donor out to lunch to build friendships and keep the faith in our organization. At the end of the day, whispers of my own art creep cautiously back to mind, but an ED position entails enthusiastically promoting other people’s creativity. Fortunately, this is a creative act as well— we gallery directors, curators and others involved in the arts can proudly regard bringing talented artists’ work to light as a very imaginative, innovative accomplishment.

Working in the nonprofit world has given me a renewed appreciation for teaching. Over many decades, I would hand in my final student grades in late May and become free to direct my full attention and psychic energy towards my own art during the next precious three months. It’s a whole different mindset running a fragile nonprofit where one begins each new year starting at zero, then faces the daunting challenge of raising several hundred thousand dollars over the next 12 months. You never dare take your eyes off the road. My family has a rustic cabin near Lake Tahoe that has no cell reception (thank God). Yet each day, I find myself hiking up to the 7000 foot elevation until my cell phone pings to life and 20 emails come blinking in with their anxious little blue dots. I then sit, ironically, surrounded by nature putting out fires in a distant art gallery.

What are some of your proudest achievements?

I’ve always thought teaching was my true calling and I’m proud of my time in the classroom helping a few thousand people develop their own voice in photography. And now, leading the historic Center for Photographic Art is a true privilege and I’m proud to say the organization is in better shape than before I began my reign of terror. Thanks to our incredible staff, trustees and generous volunteers, our membership has doubled and our finances have risen 15 fold, putting us in good shape to continue a healthy future. I’ll retire (once again) this June and pass the torch to the incredibly capable Ann Jastrab, then put on my artist’s beret. I’m a Gemini and dearly wish I could leave one of me at the CPA gallery desk and put the other me to work in my art studio.

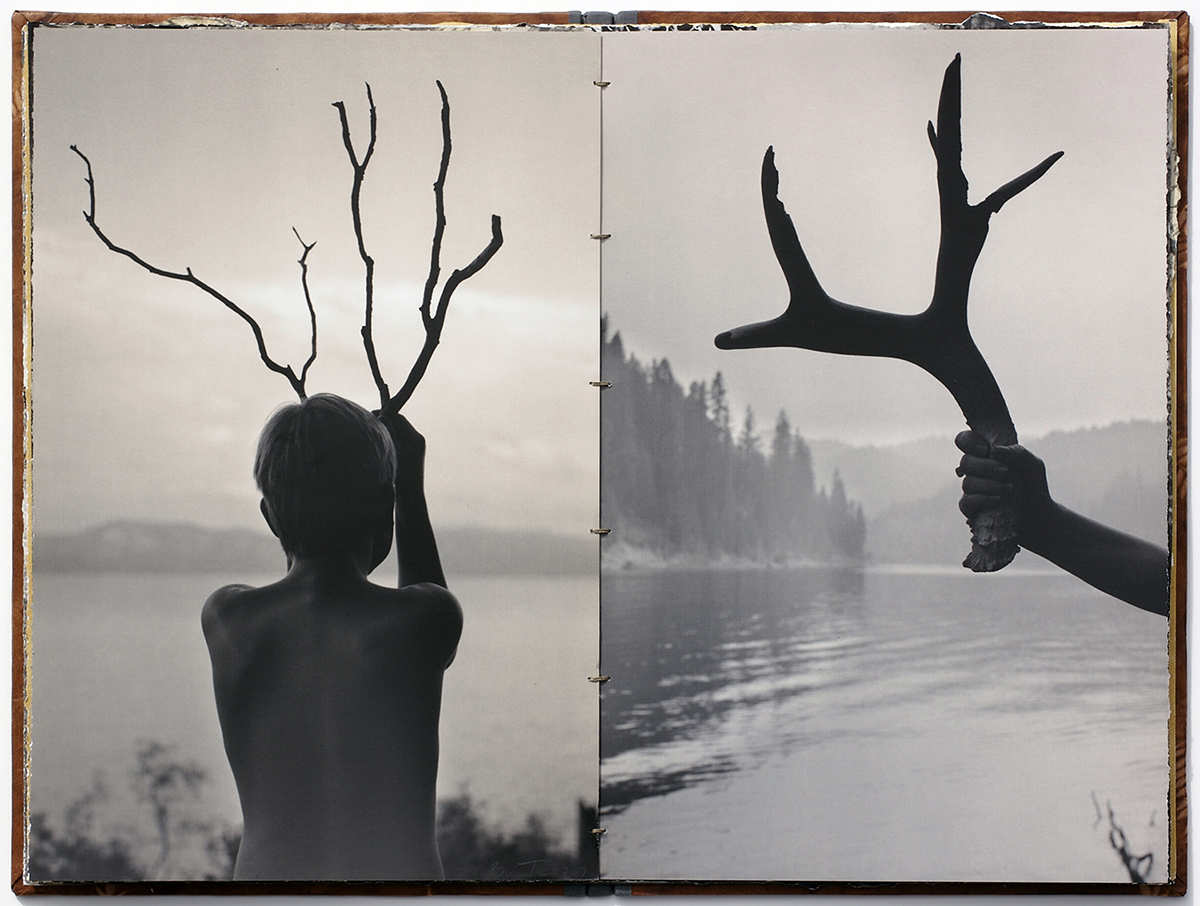

Beyond teaching and “nonprofiting,” I’m most proud of my patient and photogenic family. My talented wife is usually my model (just as Edward Hopper posed his wife Jo). I also have two incredible sons (who look like a perfect combination of my wife and the pool boy). We’ve had so many epic adventures together, and will again on the play at Burning Man later this summer.

How can photographers get involved with CPA?

The best way in the world to inspire people to get involved with the Center for Photographic Art would be for us to hire the amazing Ann Jastrab as our next Executive Director. Wait— we just did! As everyone knows, Ann rocked the house (and the City) during her ten year reign as the Gallery Director and overall Belle of the Ball at the powerhouse RayKo Photo Center in San Francisco. She’s one of the most popular and accomplished portfolio reviewers coast-to-coast, has curated dozens of exciting shows, presented numerous lectures, juried exhibitions, thrown art parties, taught workshops, and coordinated everything possible in the wide world of photography. CPA is incredibly fortunate to have her take the helm on June 1st. Brace yourself— Hurricane Ann is headed for Carmel this summer!

Any advice for photographers coming to a review event?

Try to create a consistent thread or theme in your portfolio. A consistent voice is a sign of maturity in an artist, rather than a scattered presentation of random “greatest hits.” Maturing as an artist and finding your own authentic voice takes time, years actually. Don’t seek fame and approval before the work is ready— you’ll be setting yourself up for a lukewarm reception and disappointment. Most importantly, never let anyone take the wind out of your sails. Listen with one ear open and one ear closed. You’ve gotta have thick-skin in the jungle of today’s art world! Always remember that each portfolio reviewer and every juror brings their own bias, baggage and perspective to your work; a single person can be wrong. Show your artwork to several people you trust and listen for a consistent observation that runs through all. Then you might begin to take such a common perspective to heart. In the end, take the path you must take, for as Henry Miller concluded, “Paint as you like and die happy.” Perhaps the best advice comes from Rilke writing in his Letters to a Young Poet: “Sit with yourself in the dark of the night and ask, must I?”

When I review a portfolio, I look for a sense of courage and curiosity in the work: I’m drawn to photographers who are obsessed and undaunted in their commitment to the work they’re showing me. I would be especially drawn to a photographer who is so committed, they would risk arguing with me—it’s a pleasure to encounter someone brave and confident enough to push back! And I’m especially looking for something ineffable but undeniable in the work—some sort of idiosyncratic alchemy the artist has conjured up—whether they’re conscious of it or not… A sort of brilliant/quirky, visible/invisible, hip/naïve, aware/unaware awareness!

Many participants at reviews studied photography in college, yet the statistics of how many art majors remain artists after graduation are chilling— something like only 15% three years after graduation. I highly recommend gathering your six most talented and trusted artist friends and forming a salon group. I’ve had the privilege of being part of an all-star salon group for the past couple decades. We meet at each other’s homes once every couple months and share our latest work in progress over dinner and gallons of margaritas. These gatherings of kindred spirits are immensely important— having a salon date a month away lights a fire to create art you might not have otherwise found time to do. Our group was incredibly fortunate to include the amazing David Bayles and Ted Orland, co authors of the best selling (and required reading): Art & Fear: Observations on the Perils (And Rewards) of Artmaking, so we were never at a loss for inspiration and fabulous conversation.

Salon group, back row: Chris Florkowski, Ted Orland, Saelon Renkes, Brigitte Carnochan; front row: Brian, David Bayles, Robin Robinson

What is something unexpected that we don’t know about you?

I began this interview by mentioning my fascination with Carlos Casteneda’s descriptions of “a separate reality” (the title of one of his books). I’m now curious about exploring roads to different aspects of our awareness. We humans are way too arrogant when we believe we can currently see everything that is visible, and know all that is knowable. Obvious examples abound— like the light on both sides of the visible spectrum— ultraviolet on one end and infrared on the other. Plenty of animals can see this light, but we humans are totally blind to it. This is true in so many aspects of experiencing our world. If there is something remarkable on the other side of the hill, I would very much like to see it before I die. So, I shook my snow globe, fastened my seatbelt and joined the Psychedelic Society of Monterey. (Stay tuned for further dispatches from the other side of the hill). It will be an understatement five years from now, that certain compounds (many of them purely organic plant matter) will be an incredibly valid aid to health and education (as they have been for many cultures worldwide, and before research in the US was shut down in the 1970s). If you think I’m already crazy, please read Michael Pollan’s life changing book, Change Your Mind.

And since this is a Mixtape, what is your favorite song, band, and do you dance?

Like everyone, I’ve gone through various phases and styles of music during each period of life. I wore out the grooves on Peter Gabriel’s CDs while I printed hour after hour in the darkroom aspiring to make art that looked like his surreal, hypnotic music. His live rendition of In Your Eyes is a masterpiece, as is Mercy Street influenced by an Ann Sexton poem (check out the video: a veritable Holga Camera dream sequence). For anyone about to give a presentation, listen to his Walk Through the Fire. And before you enter the crowded gallery reception of your solo show, play I’ve Got the Touch three times at max volume in your car on the way. More recently, I listen to jazz and recommend driving through Joshua Tree very slowly at twilight listening to Miles Davis’s Sketches of Spain when you’ll clearly hear the rattlesnakes in the music, the perfect soundtrack for the reptiles watching your headlights.

As for dancing, I’d only set foot on the dance floor after 12 private lessons with the ever-wondrous Lori Vrba.

And now we turn the turn-tables over to Brian who now after decades of giving back has return to his practice full time. In his words:

MY ART

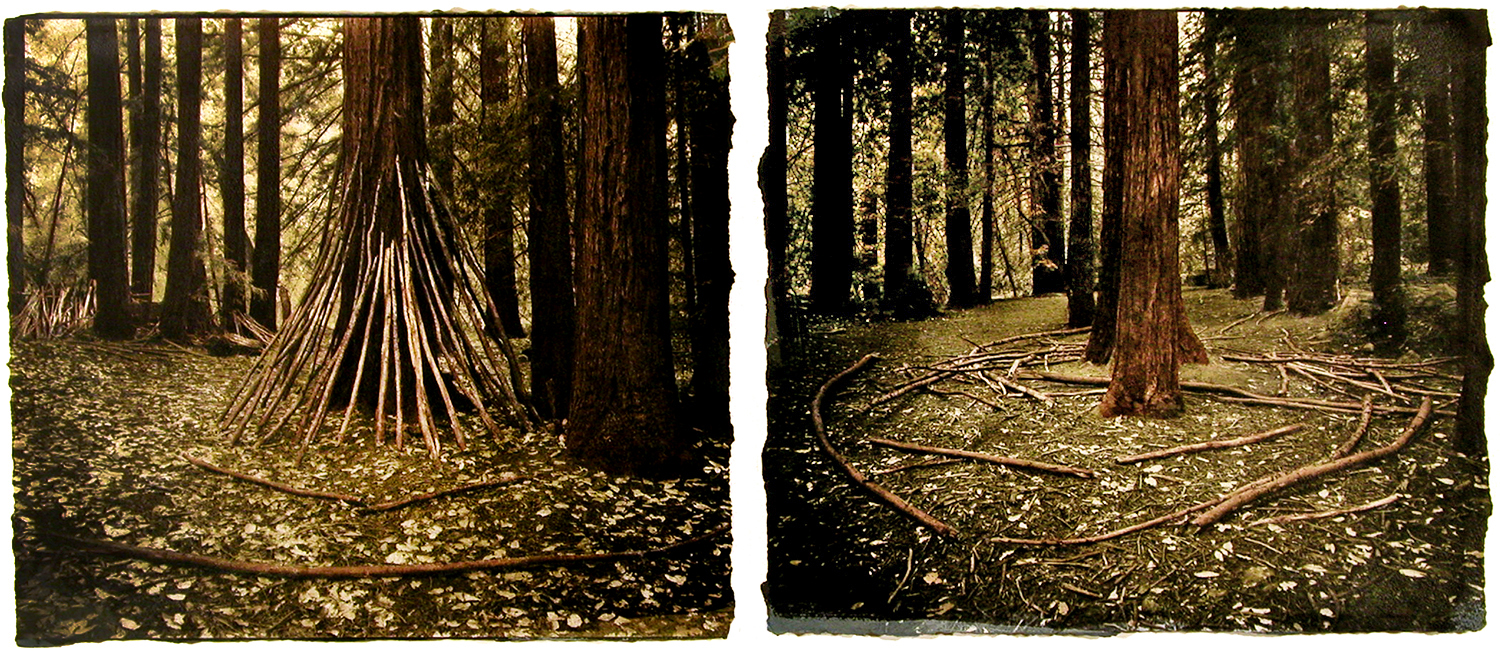

In her book, On Photography, Susan Sontag famously criticized photographers for always having to place a camera between themselves and the scene before them. Far from distancing me from my surroundings, I find that photography connects me even more closely with my subject; I never look so closely at the world as when I have a camera in my hand. And printing the images later in antiquated photo processes reengages me with the subject in an almost humorously intimate way: a gentle brushstroke here, a rub of my fingertip there, soft puffs of my breath on the print surface, rhythmic agitation, and of course changing the water as carefully as you would a cat’s bowl…

These treacherous 19th century processes afford the opportunity for serendipity, unplanned results, accidents and fortuitous mishaps. I think our viewers can sense when we have courage, when we walked a tightrope to achieve an image, and I think we’re rewarded for that determination— and good luck!

I’m a believer that people are either born tight or born loose, and it clearly shows in our art. I was born super tight, and that’s why I took so readily to the Zone System (about as tight as photography gets). I’ve spent my whole life trying to loosen up, trying to become freer in my art and give up any self-imposed restrictions. I now treat a photograph for what it really is: a piece of paper ready to be taken further, if necessary, to reach its most perfect and poetic resolution.

Living and teaching in California’s fast-paced Silicon Valley, daily life is filled with noise and chaos, so I began seeking peace and tranquility by walking alone in nature. Photographs I took during these solo journeys form the series, The Art of Getting Lost. These are my attempts to capture the essence of stillness that resides in the quiet surroundings of woods, mountains, and deserts. These are not the spotlighted grand landscapes of Ansel Adams filled with angels’ trumpets; instead, they are more intimate interpretations of the land. These images are produced using 19th Century cyanotype and gum bichromate printing processes. I savor the tactile pleasures of making art by hand: building images over time with multiple layers of brush-applied emulsions on rough watercolor paper.

While many artists feel the need to travel great distances to create art, like visiting Monet’s gardens or Versailles, I love nothing more then heading for the desert south of me in California, often with my dear friend Ted Orland. We bang around down dusty roads and discover the most surreal scenes. Out in the desert, truth is definitely stranger than fiction.

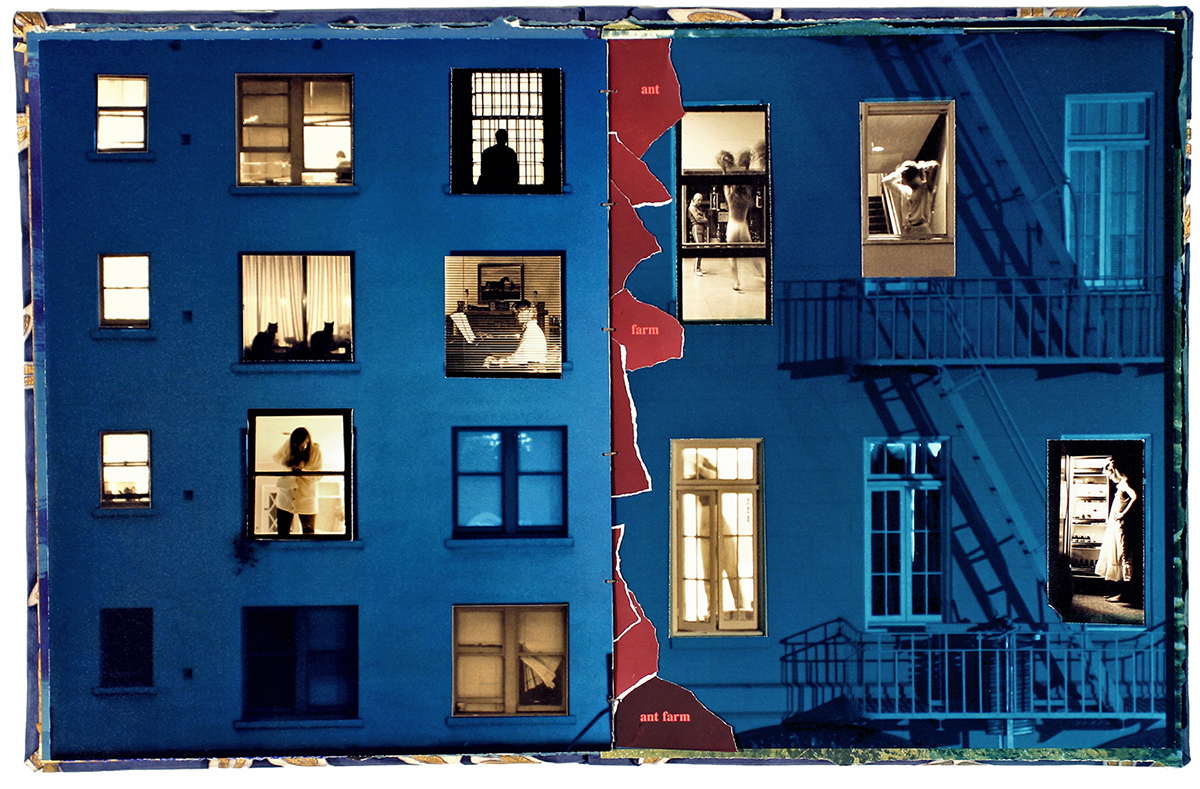

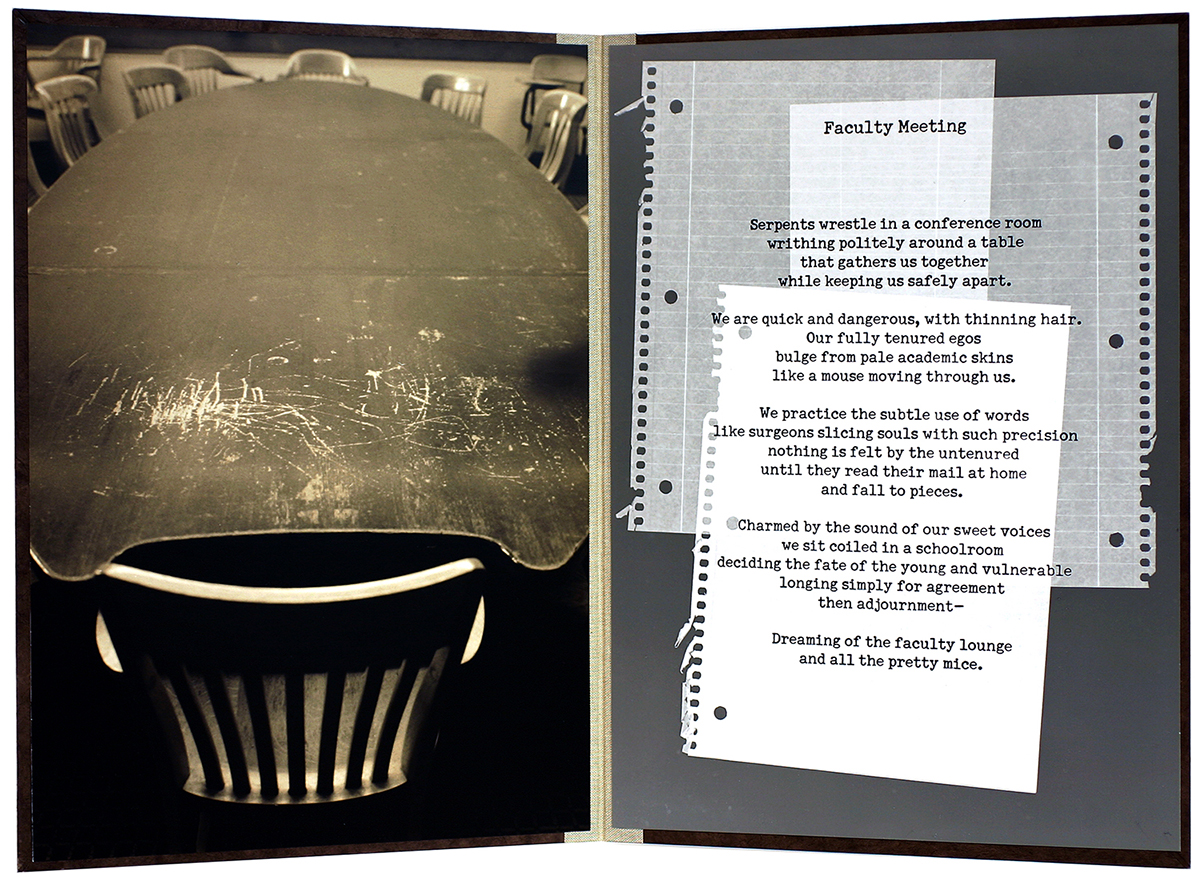

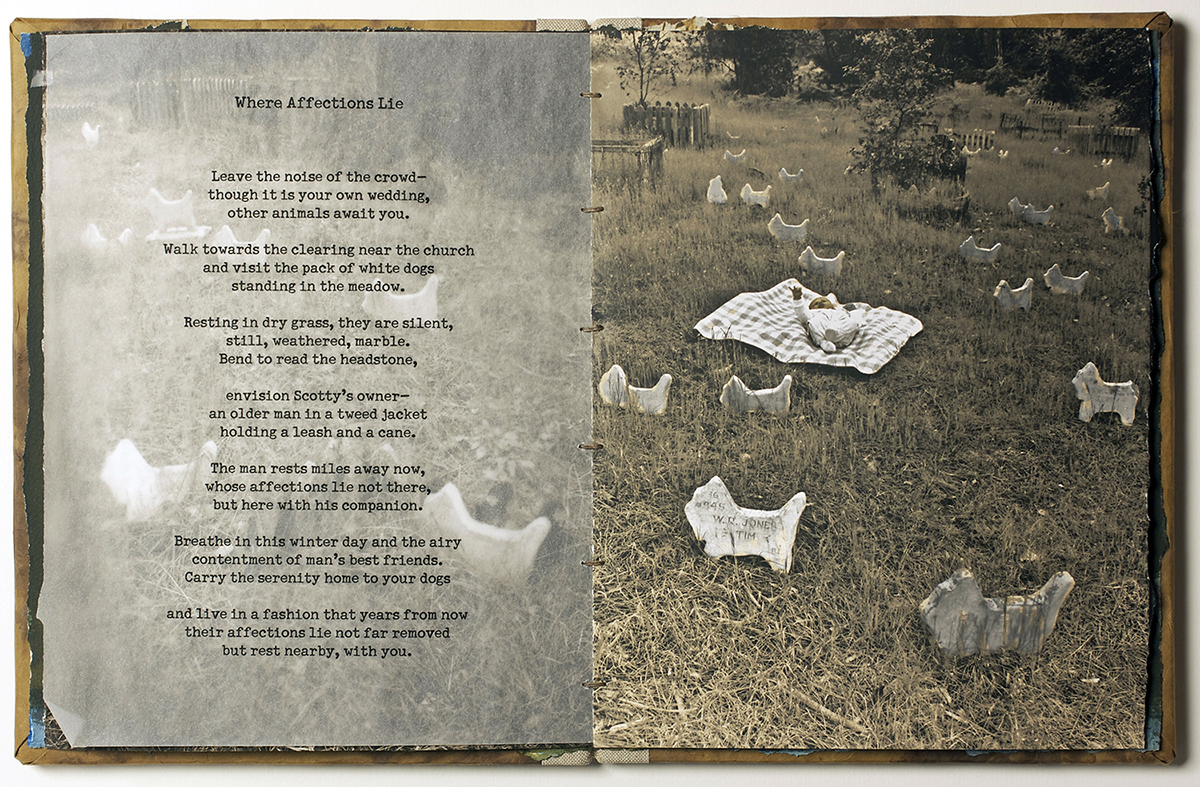

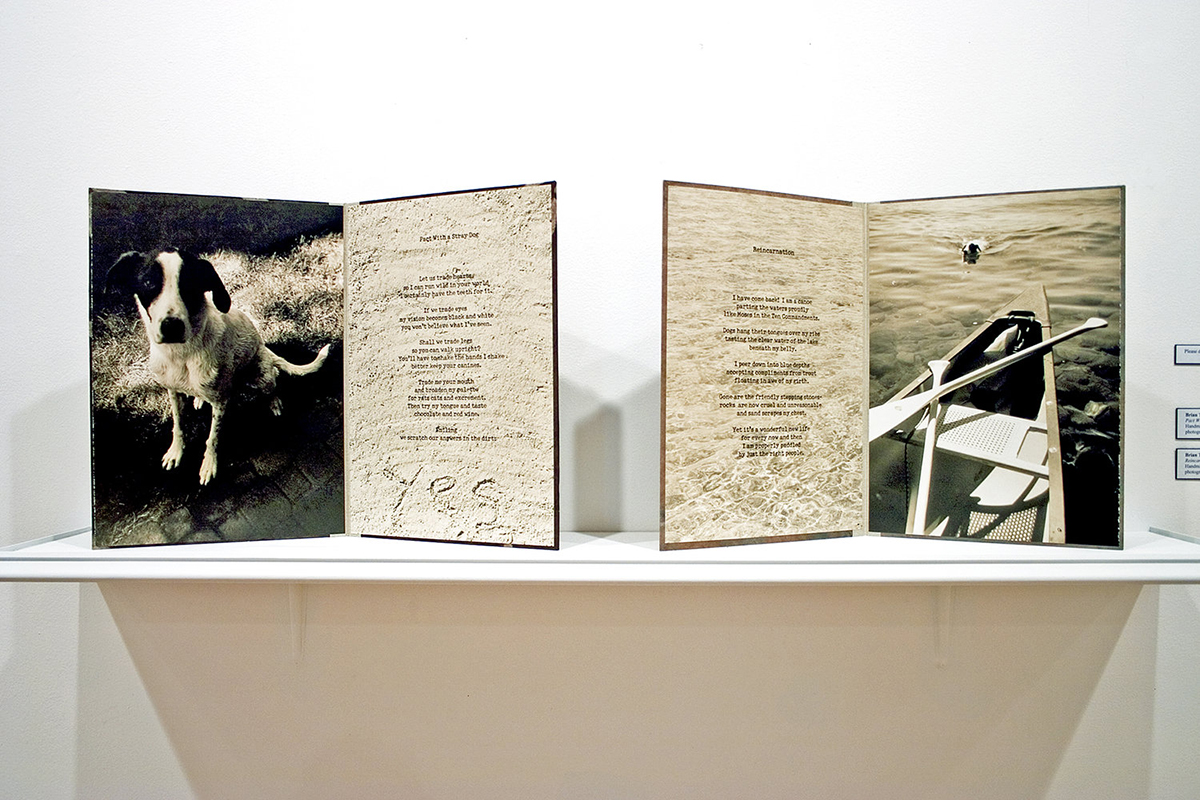

I often feel that a single photograph just isn’t enough— and search for ways to create a broader, more open-ended narrative. Through much experimentation, I began making open handmade books in the early 1990s and still find it wonderfully liberating. By juxtaposing one photograph next to another, a relationship is created, forming a marriage of imagery that is greater than the sum of its parts. This often brings a fresh, unexpected narrative. Sometimes I’ll tear pages in the gutter of my open books to include just a few words between the images, like Haiku, further expanding the work’s narrative possibilities.

And how important is narrative? Beyond the trillions of images that have been taken since the birth of photography— and now that Google Earth has photographed the entire surface of the world, one can safely say virtually everything on our planet has been photographed. Why make another copy? What people have to offer is their own perspective, the story of what matters to them in this world. Narrative is more important than ever.

I’ve poured over my photographs for years, coaxing each image to say more. A few years ago, I began exploring poetry as a way to break free of photography’s reliance upon realism; the luxury of words grants me the freedom to travel anywhere and convey whatever I imagine, without the need to stand before an actual subject.

Thank you Brian, for all you do for photography!

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Binh Danh: Belonging in the National ParkMarch 4th, 2026

-

Vaune Trachman: Now IS AlwaysMarch 3rd, 2026

-

Amy Friend: FirelightFebruary 25th, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026