Photographers on Photographers: Julia Wilson and William Glaser Wilson

This month, we feature our annual August project, Photographers on Photographers, where visual artists interview colleagues they admire. Thank you to all who have participated for their time, energies and for efforts. Today we are happy to share this interview with Julia Wilson‘s interview with William Glaser Wilson. – Aline Smithson and Brennan Booker

“There is no answer, there’s only a voice crying out in the wilderness.” I said this to Will in a critique once, long before we were married. I was responding to a comment he had made about me, and my work: “You’ve just fallen way too far down the rabbit hole.”

As I sit here trying to tell you exactly who William Glaser Wilson is, this memory continues to resurface. After thinking over our many years of critiques and love letters, and work – made and failed – I believe this encounter illustrates my relationship to Will, and our artistic practices, better than I could explain. I think this task becomes so difficult because the people we know the most, are often the hardest to explicate – much like the relationship we have to the conception of ourselves and our art. So rather than hammering out a half-way decent and inevitably lacking explanation of an artist I love and have always respected, I’ll let it unfold to you in the following interview.

William Glaser Wilson is an artist whose photographic practice strives to portray the struggles and pleasures of the everyday through constructed environments and portraiture. He is currently working on a body of work, entitled, String Theory. William received his BFA from Savannah College of Art and Design and lives in New York City.

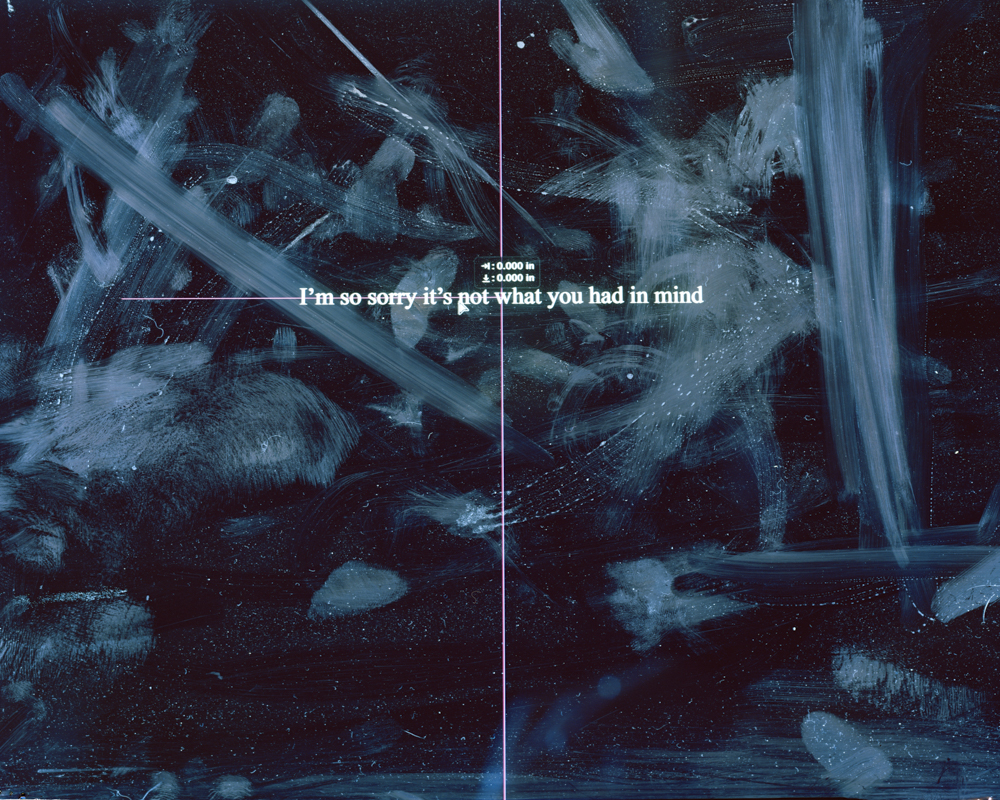

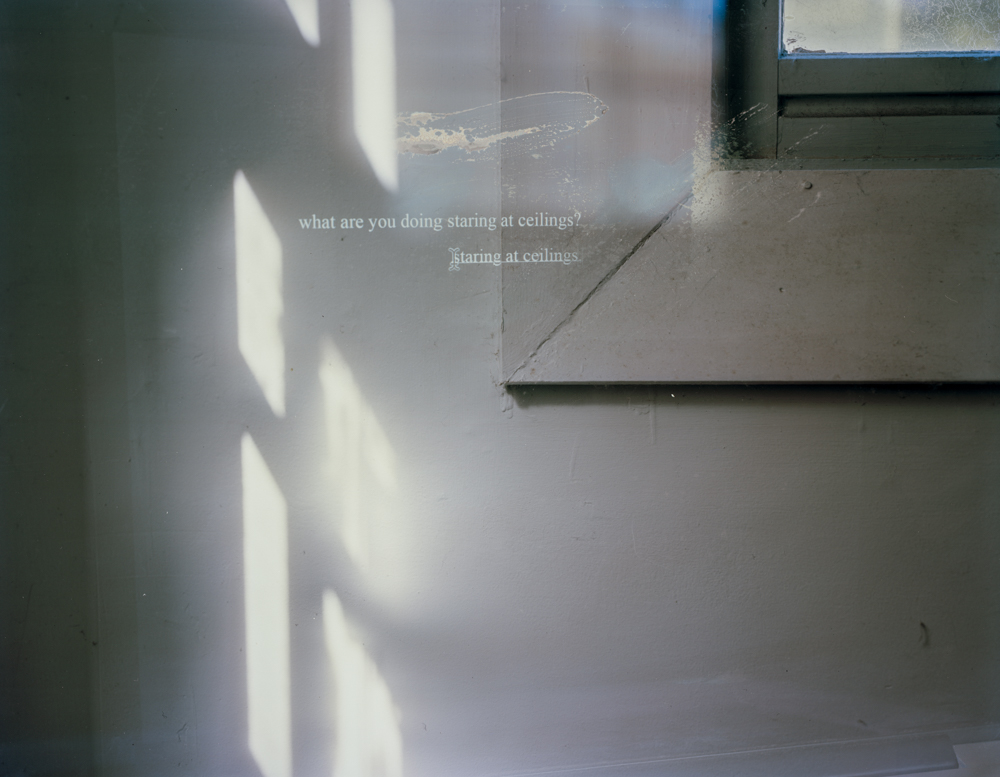

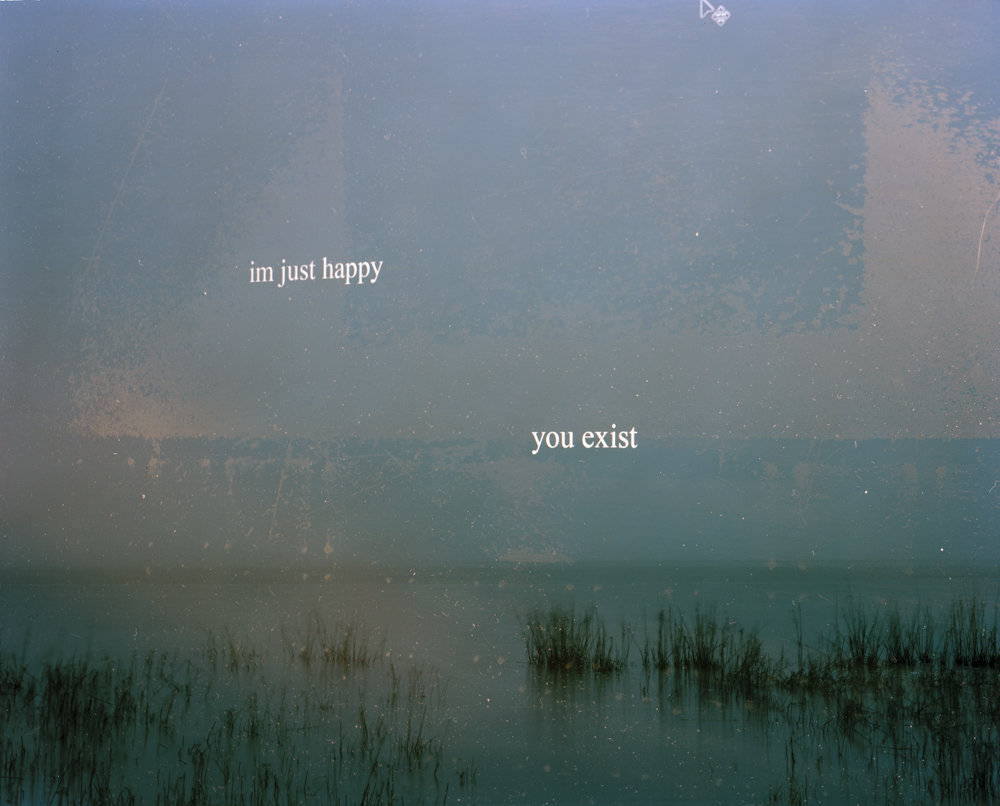

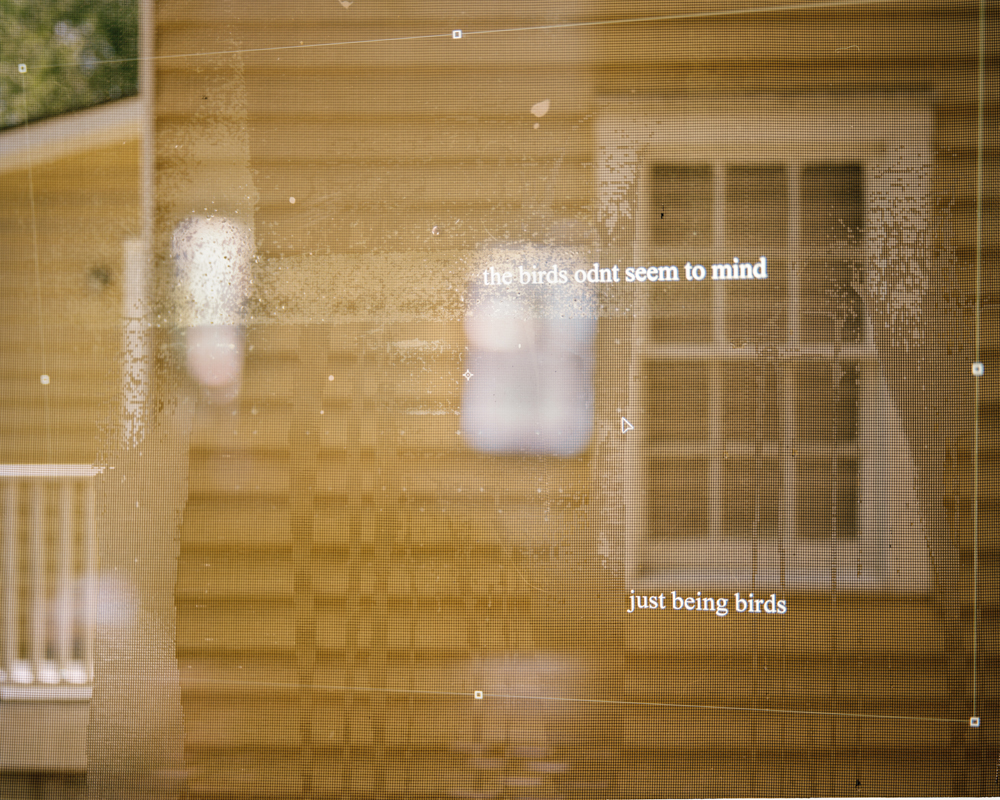

Julia Wilson is an artist whose work surrounds the relationship between text and image, and artistic interpretation in the modern world. Her on-going body of work, It is impossible to say just what I mean! has become less of a title and more of a declaration. Her practice involves photographing computer screens with the large format camera. Julia received a BA from the University of Virginia in Classical studies, concentrating in Latin and Ancient Greek translation, and an MFA in photography from the Savannah College of Art and Design. She is currently living and working in New York City.

Julia Wilson: Can you give us a background on your practice, in relation to what’s at play in your new (and working) body of work, String Theory?

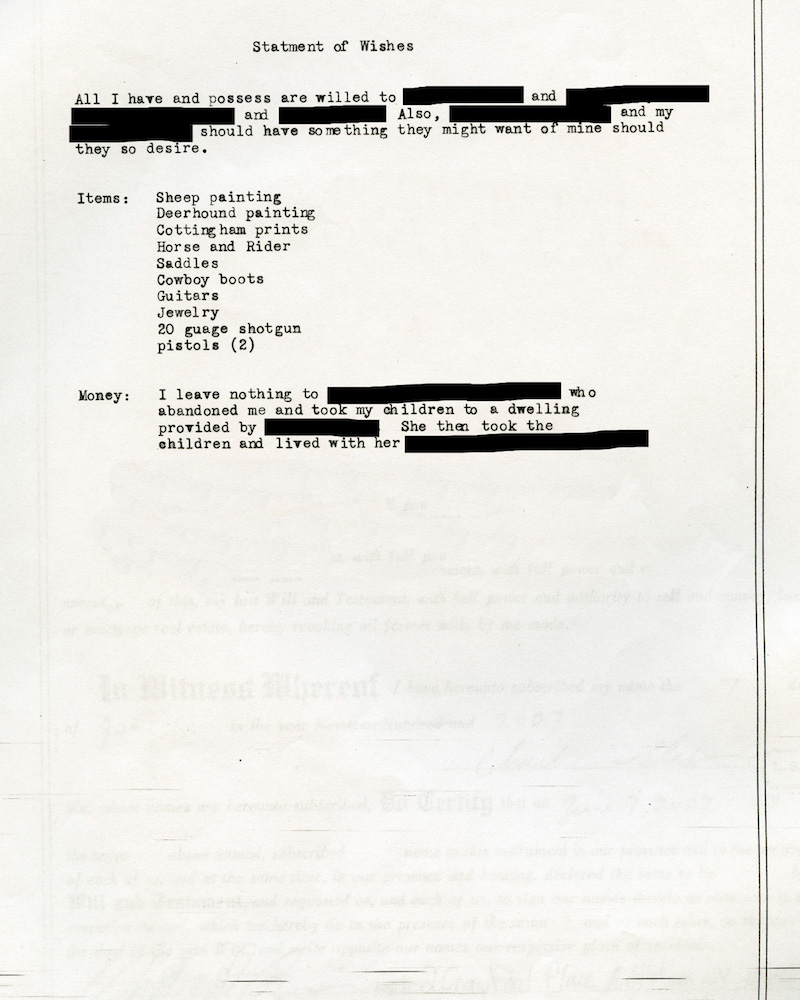

William Glaser Wilson: Ah! I can’t believe we’re doing this. Well, as you know, I would usually feel quite confident getting into the specifics of a project’s trajectory even when it would be early in the process of making the work. Previously, I would construct a thesis for a project (scripting a beginning, middle, end) and I’d execute it in its entirety, only occasionally making minor adjustments. However, if it strayed from my original parameters, I would (more or less) scrap it and write a whole new thesis. I was incredibly stubborn in what I thought a body of work had to look like, and in the end, I ended up with a mountain of false starts and half-baked ideas that never had the chance to mature. I was afraid I would have pictures that couldn’t live next to each other because of their “inconsistencies” in form, content. I’ve been thinking about photography’s place in the art world for some time, but it’s only been recently that I’ve thrown off the shackles of what I consider photography’s (and the photographer’s) greatest challenge in the art world; the ability to think beyond categorizing (or siloing) photographs based on loosely constructed (often predetermined) subject matter. While this isn’t a “new” discussion or process by any means (i.e. Roe Ethridge, Jeff Wall, Sophie Calle, et al.) it’s really a clouds-parting, heaven’s gates opening moment, when you realize a photograph is not a categorical statement, but an experiment in seeing under a specific set of circumstances.

In String Theory, I’ve allowed myself a degree of ‘openness’ that I never had before. I first became interested in the mysterious, truly enigmatic definition of String Theory. I’ll let everyone look up string theory on their own time since it’s truly an internet black hole, but just to give everyone an idea of its inception, Einstein wanted to make a single formula, or model, that would explain the fundamental interactions or mechanics of the universe. Just think about that for a moment. A math formula / model connoting the interconnectivity of all things that have been, and ever will be. After reading that, I gave myself permission to photograph whatever I wanted; as long as it moved me deeply in some way. So long story long, I have no artist statement or set plan! All I can say is I would consider the images tableaus, rather than a series of images related to one another based upon a set of characters or location. But of course, you’ve been working in this manner for some time- and I’m late to the party.

JW: It’s funny because I don’t think this working method comes out of left field in relation to your previous work. I feel like you’ve always taken artistic liberties within the storylines you create for yourself. Letting the work mutate, and take on a life of its own as you go. This just seems to be amplified version of your process.

It seems to me that you’ve cooked up a perfect storm to allow unconscious undercurrents within you to surface in order to allow the work to, in the end, speak itself to you, rather than you speak it. This might sound like bippity-boppity nonsense, but I think that is what has gotten lost on photography in the modern world. The unceasing search and rescue of an artwork’s meaning – this pressure weighing on both the viewer and the creator.

Our minds are capable of storing countless feelings, stories, images, and words, and it’s only until these fragments unite and materialize that something mysterious and magical happens – forming something altogether new; it’s never a sum of its parts, and it’s always distinct from the event.

I become especially troubled when I am asked where I come up with the words and phrases in my on-going body of work, It is impossible to say just what I mean! And not to say that this is a particularly bad question to ask, but often times I am left without words to explain – and it’s not for lack of trying.

I truly believe that art is not self expression, yet it feels most times like the dearest and most personal thing to me.

So although I used to think our photographs were situated on opposite ends of the universe – and aesthetically this might stand true – I’ve come to find that they are actually quite similar. I am not sure if that is a product of our geographical proximity (our studio apartment), and that fact that we force each other to read yet another article on language (me) or Jeff Wall (you), or if it’s in our shared attempt (and I emphasize attempt) to completely surrender ourselves to our work: our innermost feelings no longer gaining significance in our personal histories, but letting them create a life in the work itself.

As we know, this isn’t always easy, and sometimes it feels impossible, and many times we can’t.

WGW: I think the greatest challenge I’ve come across (as of yet) is trying to stop myself from inserting me into the work. We as artists, writers, musicians, performers, are well aware that the public will judge our work, so in order to distinguish ourselves, we feel as though we must individualize, almost scream out in each artwork that this [the work] is me, William Glaser Wilson, in 2019, etc. as opposed to this is us. While the optics of technology and fashion might date art, the human experience is a timeless endeavor that continues to evolve, yet key elements remain. The stories of the Bible and Shakespeare are just as relevant as they were then as they are now. This isn’t to say that we mustn’t have a point of view, rather, that our work shouldn’t begin as a statement of intent, but an attempt to connect through our common humanity. Lord knows how many photographs you’ve made me reconsider, because I was starting to proselytize or go down the road of concocting a Gregory Crewdson level production. And yet you toe that line of personal and universal so well. I remember during your MFA thesis show someone came up to you, saying, “I get it…your work is about being transgender.” I think that’s the most amazing compliment you could ever receive in your artist career! Even though that wasn’t how or why the work came about, someone was able to look into your photographs and lift a piece of themselves from your selection of text and image. Almost like a Rothko or a Twombly, you stare into the abyss and you come back with your own treasure of interpretation. Something like this isn’t possible when you start out thinking “I want people to….” But who knows! Maybe I’m being too esoteric.

JW: Not at all. And yes, that was an extremely moving moment. I think we all just strive to touch even just one viewer with our work. But I don’t think you should ever fight off putting yourself in the work. It’s all an extremely delicate dance – the push and pull between the contemporary individual and our historical sense. As T.S. Eliot might pose: how to make work with more than our own generation in our bones – where the timeless and the temporal meet.

To experience art is different than any other experience we undergo in our day to day life, but at the same time art deals with our unique experience as human beings on earth: passion, joy, sorrow, love, imagination, consciousness…how do we recreate that?

I think to make meaningful contemporary work, we have to labor to learn what came before us. From the Iliad to the Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock to the paintings of Cy Twombly – the poets and artists, who gave their life’s work attempting to understand the human heart at odds with itself. Otherwise art is defamed to trend, fashion, and politics, and I refuse to accept this.

WGW: As someone who became interested in photography late in college, I toured quite a few academic departments before finally coming to art. I was originally interested in Philosophy because I felt (and still feel) that technology is never stable, and you’re only able to understand and utilize technological instruments up until a certain point. Think about it; you teach older folks how to attach images to emails, etc. and chances are one day, the roles will be reversed and you’ll be asking how something works [this has an interesting degree of intersection when it comes to film and digital photography, but that’s another discussion]. However, learning to think for yourself and becoming an individual (whether that be in the arts or developing a new marketing strategy for an advertising firm) is a timeless skill that doesn’t have planned obsolescence. Similar to yourself (or maybe I’m just projecting), I was quite often asked “what am I going to do with a degree in xxxx?” in a tone that was undoubtedly condescending. To me, being taught the history of ideas, and dissecting various philosophers writing, hearing them pondering what constitutes a “good” life was not only incredibly fun, but life changing. Allowing yourself to be open to other ways of looking, or thinking, can drastically alter what you find interesting and consider worth showcasing to others.

‘An Apology to Idlers’ by Robert Louis Stevenson is a book that had a great affect on my current photography process, and especially String Theory. In previous projects, I was interested in creating these low-budget cinematic photographs where it’d be posing people I’d find on the street (or through friends) to perform in front of the camera. While I may have considered them “dynamic”, I was asking people to do things that were clearly done with a camera “catching” them in an unnatural act. ‘An Apology to Idlers’ (indirectly) made me realize the most interesting moments (albeit, almost impossible to photograph) in your life are when you take a deep breath of fresh air in the morning, or walk in a deep part of the woods that was previously unknown to you. This all sounds commonplace, but there’s something to be said about photographing someone just doing a human act as opposed to performing in front of the camera. It took me a while to find this place, but through enough trial and error, here we are.

JW: I have such a weird relationship to trial and error – because I live in this state of experimentation. And while it’s brought me my best photographs – photographs I could never recreate- it’s also brought me numberless failures. But, hey, if I was efficient I would have been a banker.

So today, as you know, I scanned a few more negatives for my one and only project, It is impossible to say just what I mean! I am still working out the kinks, still getting a ton of failures, and as far as those deemed worthy, I am keeping the cards close to the vest. I know you are too, for the most part, so I am so happy I could convince you to share a few with us today.

I am going to leave us with a quotation by William Faulkner that’s stuck with me over time:

“All of us have failed to match our dream of perfection. I rate us on the basis of our splendid failure to do the impossible.”

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026