Stig Marlon Weston: Back to Nature

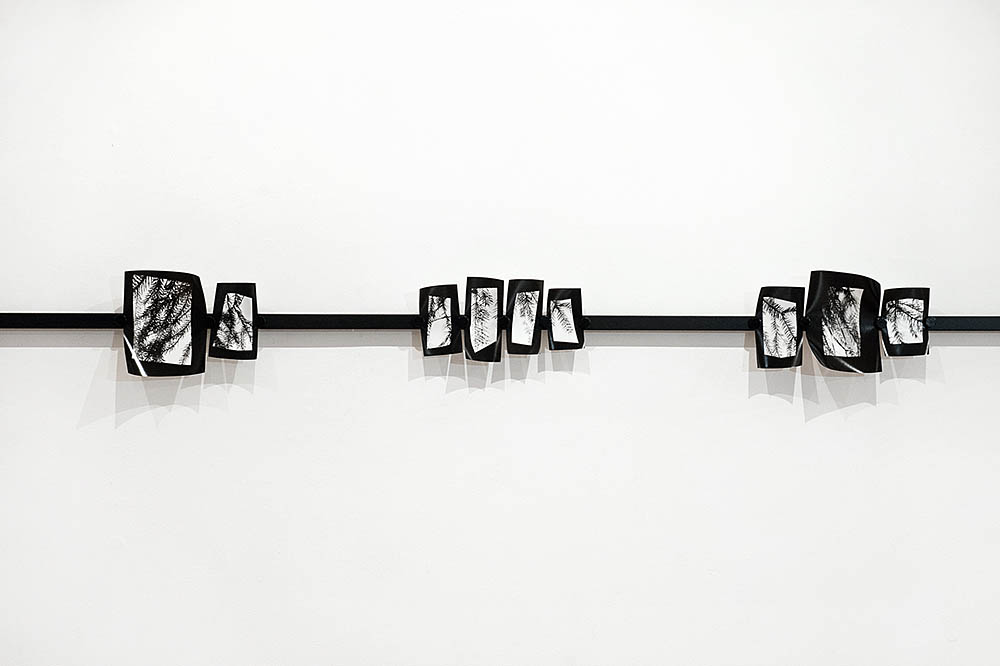

©Stig Marlon Weston, Trunk from Grove. Exhibition installation of “Grove” showing sets of medium sized “Trunk” prints.

‘In every walk in nature, one receives more than he seeks’. John Muir.

As photographers we are accustomed to controlling our camera, lighting and subject matter to determine our creative voice. Norwegian artist, Stig Marlon Weston turns this approach upside down. He believes that the camera can sometimes be limiting and instead chooses to let go and allow space for chance to play an early and significant role in his output.

An avid experimenter with alternative camera-less processes, Stig creates a different process for each of his projects designed to be in harmony with the subject and allow its qualities to flourish. Light sensitive film may be pinned to a tree for one minute or light sensitive paper propped up in a rock cairn for 24 hours. The former to reflect a child-like view of the landscape, the latter to create a more spiritual effect. Alternatively the soil may be sampled photographically to show a scientific perspective.

Throughout, Stig’s work displays a strong sense of the physical connection between the original subject matter and the final image, which made an impression at CENTER’s Review Santa Fe this past October.

©Stig MarlonWeston, -Exhibition installation of the “Cent Cims” series of photograms of rock cairns from the pilgrim paths on the Montserrat mountain.

Your work is highly unusual. For our readers, let’s take a step back and find out how and when this all began?

Like many other photographers, I started out in my school darkroom. I enjoyed the hands-on process and applied to do my second year of photography college at a school located on an island in Northern Norway. The school had special State funding which allowed it to offer both free use of materials and 24-hour access. I spent my time experimenting and discovering techniques that I would only later read about in books. Learning that I was only rediscovering the work of other people gave me a sense of being on the right track and inspired me to push forward. This soon became my modus operandi; I experiment and discover, and then I look to see what others have done that may be similar.

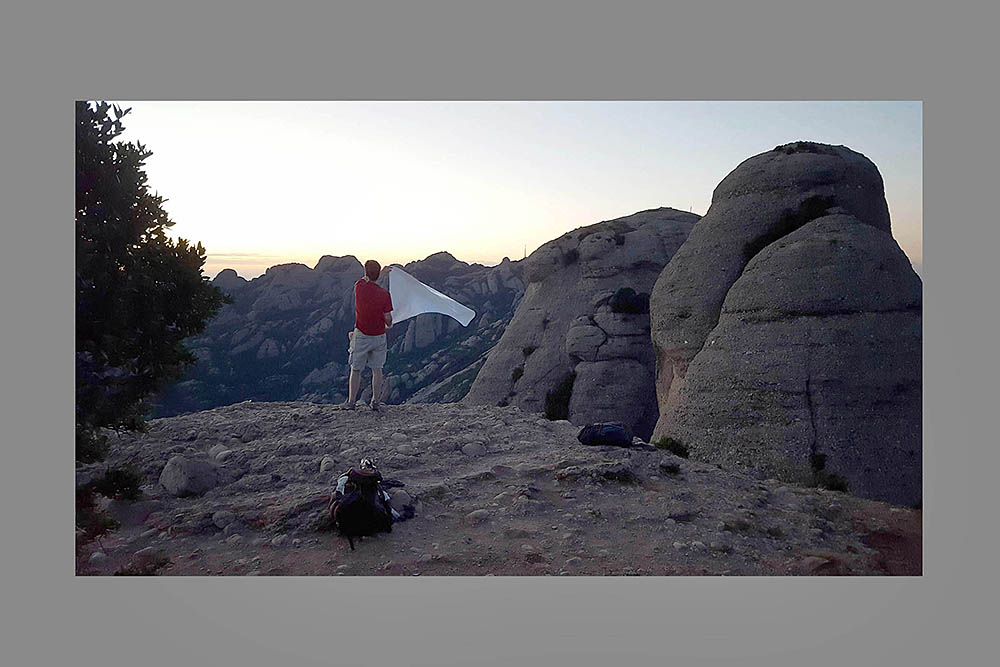

©Stig MarlonWeston, -Stig Marlon Weston exposing the photopaper in the sunset light on top of Montserrat Mountain, before making the “Landmark” chemigram imprint of the mountain peak St.Magdalena.

Your choice of technique is intriguing. You refer to a Lumen print which typically is a solar photogram. How does your particular process work and where, if at all, does digital imaging feature in your work?

In the beginning I worked a lot with photograms, on paper and then film, exploring how to make prints that are not only abstract but actually show another side of the subject. When I decided to take my processes outside I had a hard time protecting the material from overexposure. I ended up letting go of all restrictions and learned how to work with overexposed material. When making my first outdoor paper photograms I realized the more exposure I gave the paper the better the results. It wasn’t until after I had made the work that I checked out the works of others, and learned what it was that I had created – lumen prints. Now my prints are usually exposed for at least a 24 hours. This allows the image to get all the daylight and opens up for weather, changing air humidity, and the movement of the light, to influence the paper as well.

Digital imaging doesn´t really feature much into the process, apart from testing ideas. I often rephotograph my photogram negatives to try out the look of different printing contrasts on a screen before I go into the darkroom to make my contact prints. What is important to me is the shared interaction with light and chemicals that allows me to keep a physical connection between the original subject and the final image. Digital processes insert a black box of uncertainty where you cannot any longer trace this connection back to the source.

How long have you worked with these processes? Do you see a time when you’ll reach an end point? When you need to move on to something different? Or, has working in this way shaped who you are now and you can flex the content almost infinitely?

I have been experimenting in the darkroom for more than 25 years – my whole adult life. So I don´t really believe there is an endpoint anymore. The trick is to keep playing around, and making sure that I keep more ideas in the drawer than are being used at any point. The goal for me is not to do something crazy or make weird looking photographs, but to use a process that makes sense of the subject matter I want to work with, and to save any other ideas for later use.

However, I would like to point out that my way of thinking about photography, has also opened up my mind for how I work with more traditional techniques as well. I do use a camera sometimes. However, I am more aware now, how the technique and equipment we choose to use can limit and steer our work, so much more than we should let it.

©Stig MarlonWeston, -Stig Marlon Weston developing the “Tears of St Lawrence” chemigram imprints outdoors at the Can Serrat art center by the foot of the Montserrat mountain.

Divinations

Made during two artist residencies in Spain, at the Can Serrat art center by the mountain of Montserrat. The mountain is regarded as holy and the spiritual center of one of Catalonia´s patron saints, la Moreneta – the Virgin of Montserrat.

I explored the mountain and the story of mystical lights that are said to be seen in the sky there. These cameraless photographs shows how a mountain can make it´s own portrait, telling a story that let´s us interpret the history of the place from a new vantage point.

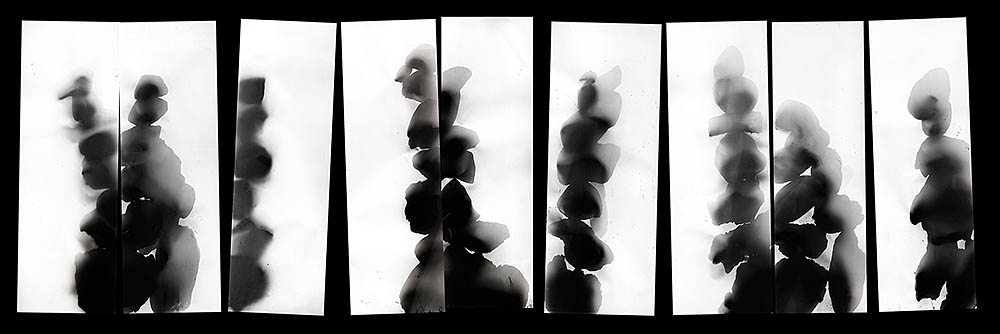

«Cent cims» is a series of heliograms made outside on the mountain. Montserrat is also called La muntanya dels cent cims in catalan, which translates as the mountain of a hundred peaks.

These are unique prints made directly on vintage photographic paper, depicting the imprint of stone cairns along the mountaintrails, guiding pilgrims and travellers along their way.

“Celestial” is a series of pinhole photographs showing the sunrise or sunset from the vantage point of different mountain peaks.

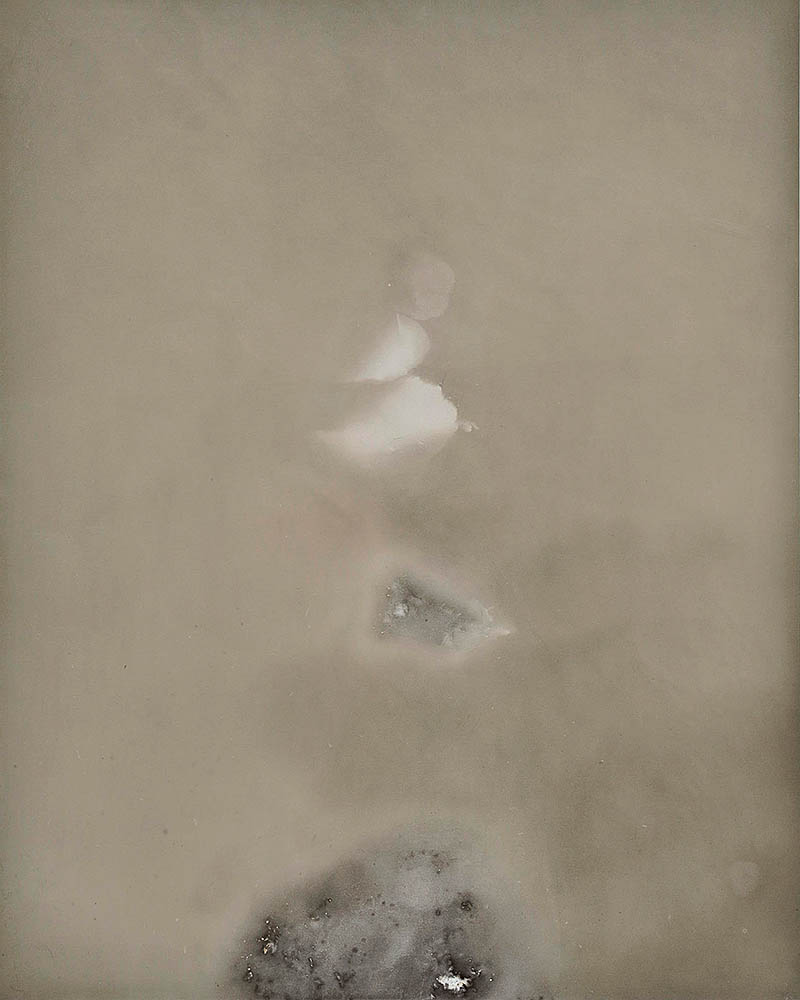

“Landmarks” is a set of chemigrams with imprints made of the physical mountainpeaks. These are unique prints made directly on vintage photographic paper, showing the rockface on the tip of seven different peaks.

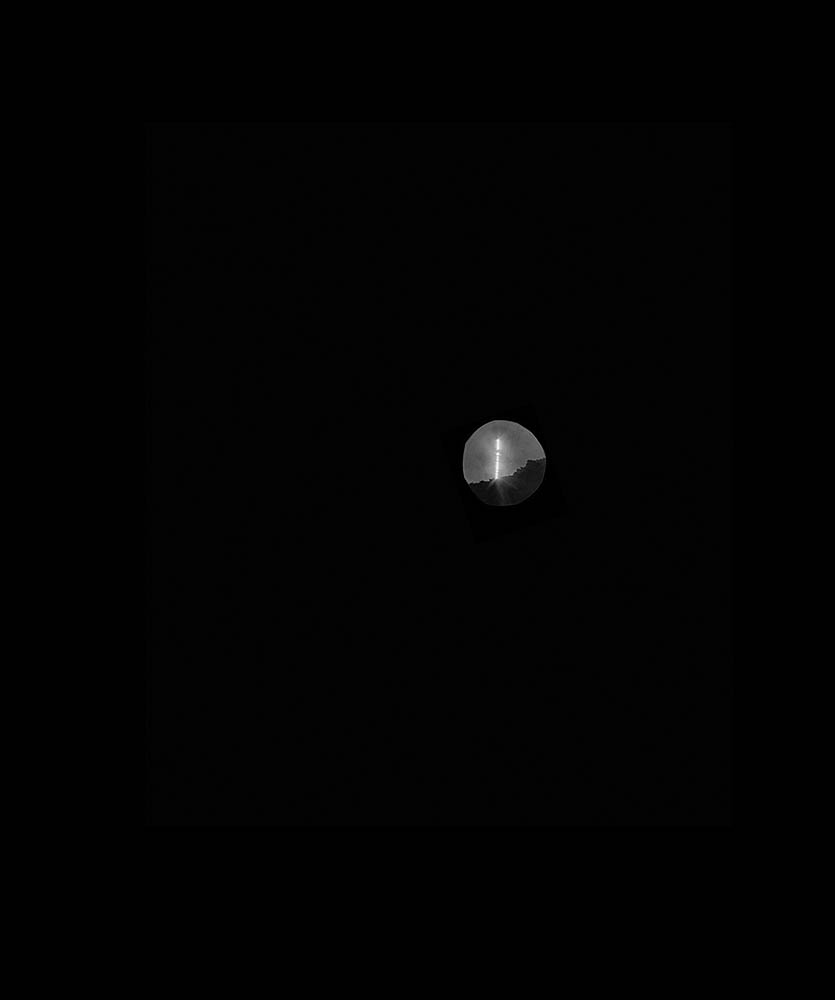

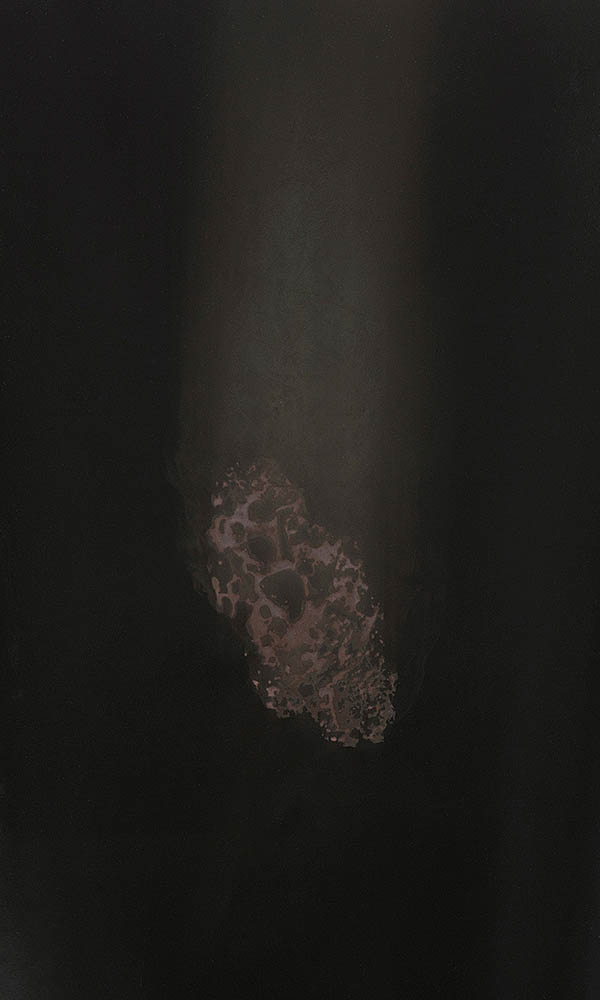

«Tears of St Lawrence» is a collection of chemigrams of pebbles taken from the top of the mountain. The title refers to the old popular name for the Perseides meteor shower, and the images shows how the rocks might have looked as meteorites when seen as lights in the sky.

These are unique prints made directly on vintage photographic paper that can be mounted as a wall installation.

“Perseides” are unique prints recreating mountain rocks as meteorites lighting up the night sky.

©Stig Marlon Weston, Exhibition installation of the “Landmark” series of chemigrams of mountain peaks from the Montserrat mountain.

©Stig Marlon Weston, Exhibition installation of the “Tears of St Lawrence” series of chemigrams of small rocks reimagined as meteorites from the Montserrat mountain.

©Stig Marlon Weston, LaPalomera sunrise from Divinations, A pinhole photograph of the sunrise over the mountain range Montserrat as seen from the peak of La Palomera mountaintop.

©Stig Marlon Weston, Cent Cims #8 from Divinations, A photogram of a rock cairns from the pilgrim paths on the Montserrat mountain.

©Stig Marlon Weston, Cent Cims #100 from Divinations, A collage of film photograms contacted printed together, showing rock cairns from the pilgrim paths on the Montserrat mountain.

©Stig Marlon Weston, Perseides #2 , from Divinations. A chemigram imprint of a rock reimagined as a meteor from the Montserrat mountain.

©Stig Marlon Weston, Tears of St Lawrence #45, from Dicinations, A chemigram imprint of a small rock reimagined as a meteorite from the Montserrat mountain.

It can’t have all been smooth sailing. Please tell us about some of your setbacks and your learnings. What is the hardest part of creating these projects?

The main difficulty for me has been the time it takes to make this kind of photography. There is a lot of experimenting and serious work with ideas and processes that turn out well, but not useful for anything yet.

Then again, in a while it might be really important and useful for something else and not a waste of time after all! What I have learned is to let go of total control and let chance and intuitiveness enter more of my processes. And I mean that on the most basic level. I find that I am more creatively focused when I decide to try and make something out of a setup that I don´t believe will work. When I go to a new place with no darkroom, equipment or known way of handling the materials I use, it forces me to build or create only exactly what I need. And then I improvise the rest. This gives more influence to the place I am in and its impact on how the pictures are made.

I think the hardest part in my work is keeping focused on the right goal. My aim is really not to make an interesting image the way I want to see it. But instead I try to create a process that will capture what my subject would find relevant and interesting and then I allow for this process to dictate as much as possible of how the image turns out. In a project like «Grove» this can play out with me looking for a forest tree that would make a good hiding place for an animal or a child playing hide and seek. I then hang my film behind the tree, hiding it from me when I am looking at the tree and exposing the film to light from the other side.

©Stig Marlon Weston, Grove Documentaition, Exhibition installation of “Grove” during an artist talk. Showing a set of three large “Grove” prints and a set of 9 medium sized “Trunks”.

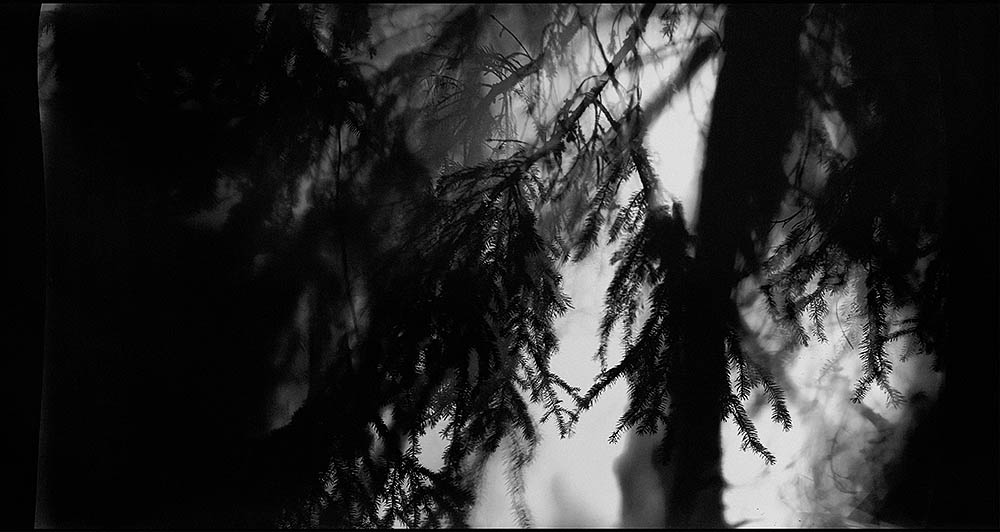

Grove

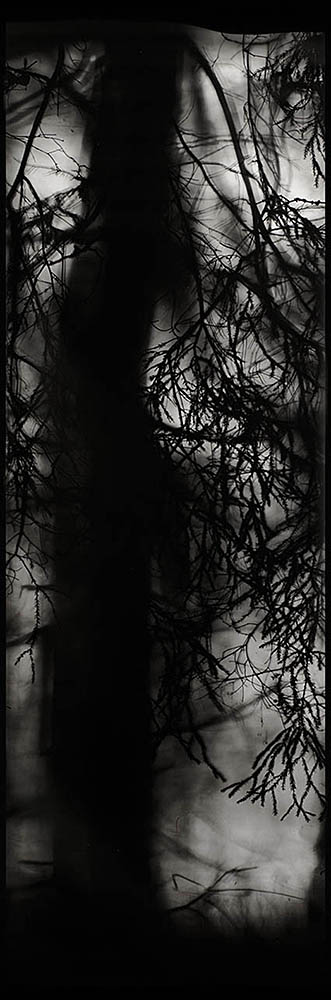

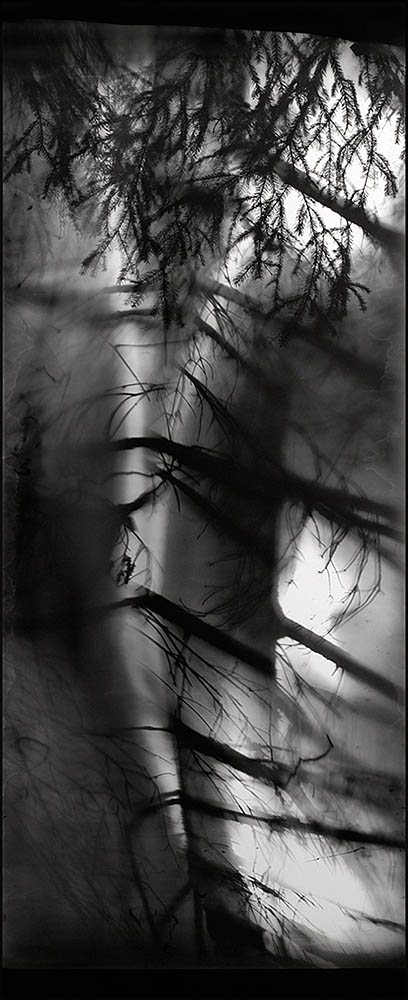

Going back along the forest paths where as child I used to hide and play and construct worlds of fantasy, I today carry with me huge rolls of film. By ditching the camera and letting the forest do it«s own dirty work I hope to catch a glimpse of that elusive primal feeling that only the innocent young and the wild beast have in common. In the middle of the night I give mother nature the means to expose herself on my canvas of chemicals. I use the film to make life size contact prints. The tears and scratches are just as much a part of the imprint of the trees as the shape and shadow they leave on the material. And looking through the places of memory, I can still find the tracks of trolls.

Prints are made as life-sized contactsheets, the largest ones measuring 106cm x 200cm-350cm. The thin stripes are from 20cm x 100cm and the smallest one shown here is 5cm x 15cm

©Stig Marlon Weston, Shoot from Grove. Exhibition installation of “Grove” showing sets of small “Shoot” prints.

There aren’t many people working with these processes that produce this breadth and depth of work. Broomberg & Chanarin come to mind. I see you as a kind of explorer. Sailing into uncharted territories. Who were your influencers/mentors and who on the current horizon excites you creatively?

Thank you for that comparison! And, yes, I do very much feel like an explorer, but more in thinking about the way I see and experience the world rather than about the technique that I am using to make my images. For me it all goes back to the idea of how to depict a mode of perception, and through that, achieve the understanding that there are very different ways of seeing, both physically and intellectually.

I haven’t been directly inspired, but I remember seeing Adam Fuss’ work early on, and being both impressed by the quality of his images and disappointed that someone else had already made many of the pictures I wanted to do. In a way I think this inspired me to press on and be more focused on knowing more about why, not only how, I do my projects.

What has worked well for me is sharing discussions and setting up collaborations with other artists. I had a loose and extremely productive collaboration with German artist Denise Winter that helped me develop my forest images that ended up in the project «Grove». Our discussions and final show helped me finally trust my instincts on how to push the limits of my ideas. Now I have an ongoing collaboration with U.S. photographer, Meggan Gould, that has been very inspiring for me in more theoretical ways. Our work is quite different visually, but our thought processes overlap a lot.

Now that experimental photographic practices have become more popular, there are many people showing this kind of work these days, But it is seldom that I recognize a sense of a deeper thought behind what is being shown. I enjoy the work of Klea Mc Kenna and Meghann Rippenhoff and am impressed with the serious way that they develop their projects. I also like the playfulness of Mike Jackson and Joanne Dugan. Norwegian experimental photographers that have impressed me recently are Aage Villy Skaaret, Federico Grandicelli, and Solveig Lonseth who are also all very focused on process.

©Stig Marlon Weston, Grove #8 from Grove. The “Grove” series is based around a series of black and white darkroom contact prints made from large film photograms of trees.

I notice that some of your work in ‘Grove’ is very expressive, almost raw. Whereas the typologies in Empirical are far more organised and quite beautiful, presumably because of your more scientific approach to the subject matter. How do you decide which techniques are most appropriate to the location?

First, I decide what theme or mindset of perception is appropriate to the location, and then I try and to find a technique and process that reflects that mindset. The Grove series is all about understanding the primal viewpoint of the landscape and in what way we would process visual information without worded language. The idea came from me wanting to go back and photograph the forest area where I grew up. Oslo, as the capital of Norway, actually has more area covered by wild forest than buildings. Wolves have also been known to frequent the forest at times. So I wanted to look at the feeling of the forest landscape as seen through the eyes of a child without language, or a wild animal. This naturally needed a raw process where the material gets to feel the place rather than to be referenced in a knowing look. While the series, Empirical, is trying to show the opposite of this by looking at the world from a scientific viewpoint. The inspiration for this series came as I was staying at a scientific research station in the Amazon as part of an artist residency program. My choice was then to collect photographic samples of the landscape in a way that follows the rules of scientific data collection and makes my images into material appropriate for study.

©Stig Marlon Weston, Grove #9 from Grove. The “Grove” series show images of the shadows of trees from the artists childhood forest playground.

Is there an underlying core message in your work? Does your work tell a story or is it more about showing us all a different viewpoint on the familiar?

I follow two main lines of thought through my photography. I find it fascinating how we all have our separate viewpoints of the world, that all are simultaneously correct but each believing that our individual viewpoint is universal. And I am interested in the way we look at and interpret the medium of photography totally different from all other art forms. Although photographs are known to represent personal viewpoints, we still relate to them as being of this world, thus being universally truthful. These two thoughts come together for me in trying to make a picture that forces the viewer to become aware of how they interpret it as a photograph and that they actually always are choosing what they see. By using experimental techniques it is harder to instantly recognize and connect to preconceptions of the photographic subject. And I find that people look deeper and show more wonder about how the world as seen through my images.

©Stig Marlon Weston, Grove #25 from Grove. The “Grove” series is trying to depict how the forest landscape can be sees by a viewer with only direct sensory experience and no worded language, like a child or an animal.

Visual artists often have other artistic interests. For example a large number of photographers were also musicians. Do you have any interests which you feel help the way you see and think? Who are your favorite artists? (any discipline)

Growing up, I tried to teach myself to play the classical guitar. Learning how to read musical scores I ended up improvizing tunes rather than learning real songs, and I guess this has set a pattern for me. I enjoy learning the basic skills of something, then I disregard the set rules and allow myself to play freely. The last few years I have enjoyed brewing beer for my studio gallery openings. I play with combinations of ingredients that relate to the season or the exhibition theme of the latest show in the gallery. After returning home from the Amazon I made a brew with coffee and raw chocolate that I bought from an Eco-farmer in the rainforest. This month I am brewing with prickly pears that I picked in New Mexico when I was at the Santa Fe Photo Review this Autumn.

I have always enjoyed a variety of creative arts and have had a few stand out experiences. Meeting the works of Mark Rothko have had the most impact on me. I clearly remember seeing his works for the first time as a child visiting the Tate Gallery on a trip to London. A later visit to the Rothko Chapel in Houston TX as an adult reinforced my belief in art as a mover of souls.

©Stig Marlon Weston, Shoot #12 from Grove. The smaller images from the “Grove” series zoom in between the trees branches and shoots

©Stig Marlon Weston, Twig #1, from Grove. The smaller images from the “Grove” series zoom in between the trees branches and shoots

Thank you and finally, you are clearly on an exciting journey. Where do you go from here?

I am planning a trip back to the Amazon to finish the project I started there, having developed my ideas and plans after my first stay. And then I am considering several different possible locations for my next project that can challenge myself towards creating meaningful imagery in new ways. I really don’t want to go to a place where I know what I will do but I am looking forward to discovering new ways I can show myself how to see the world.

©Stig Marlon Weston, Flora Elevation Sample,from Empirical. A lumen print being exposed in the Amazon rainforest as part of a collection of flora samples made throughout the different levels of elevation of the forest floor.

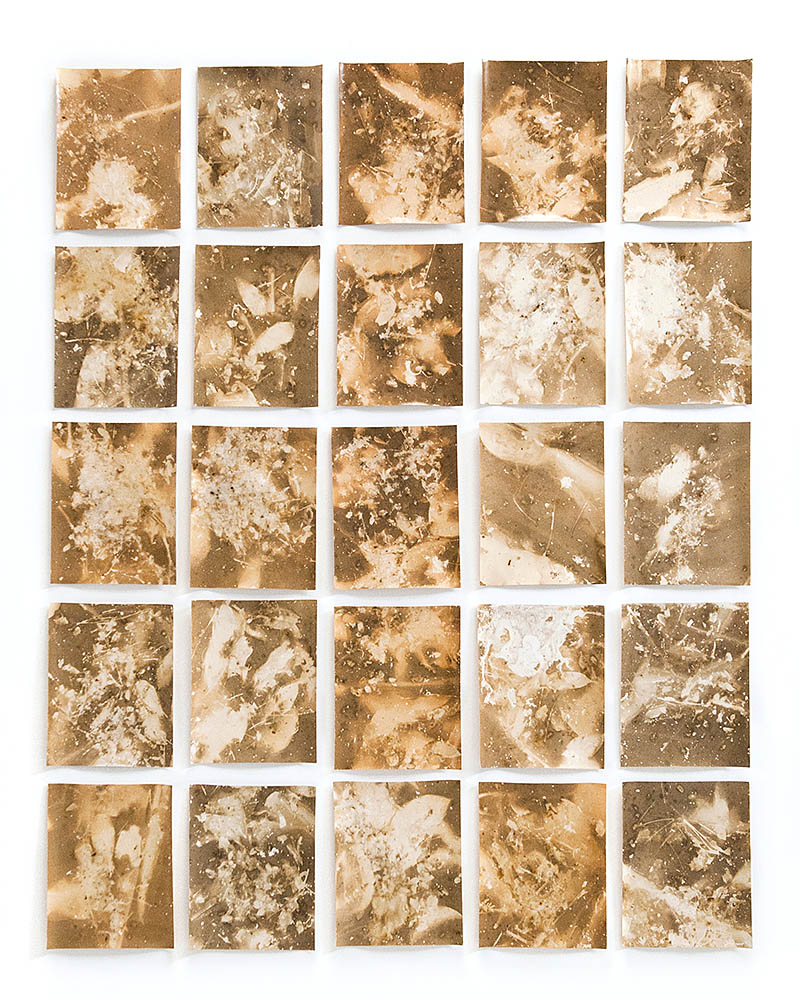

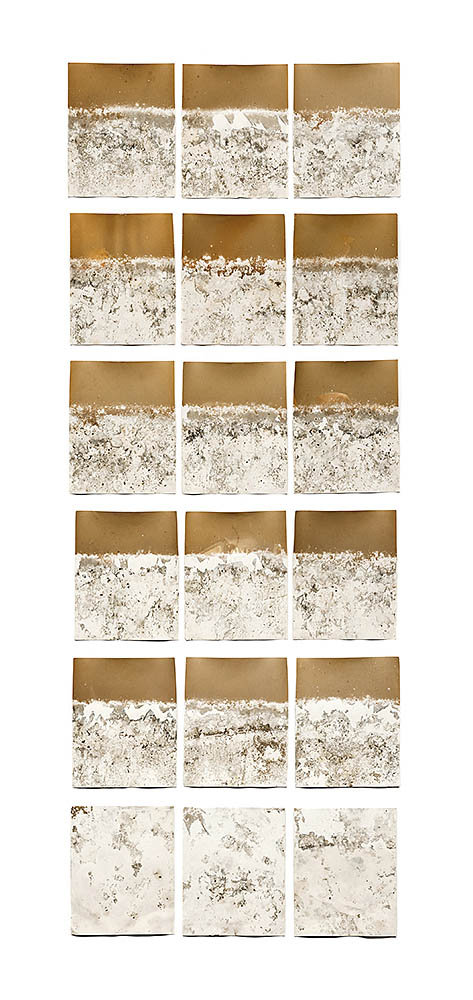

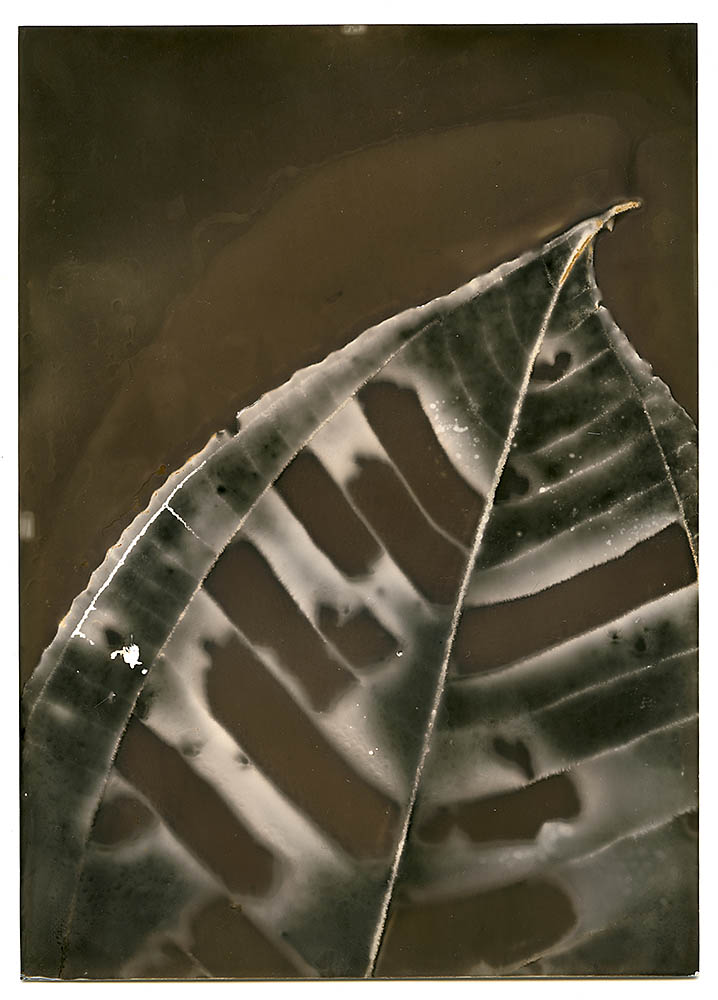

Empirical

This project was initiated during an artist residency with Labverde, at a scientific research station in the Brazilian Amazon rainforest, and will be finished during my next trips to South America. I was inspired to do work looking at the scientific view of the world, and try and catch this experience in my photographic material.

By utilizing scientifically inspired methods of collecting randomized samples and imprints of the landscape I make collages and collections of images that give a basis for new interpretations and understanding of the biodynamics at work in the rainforest.

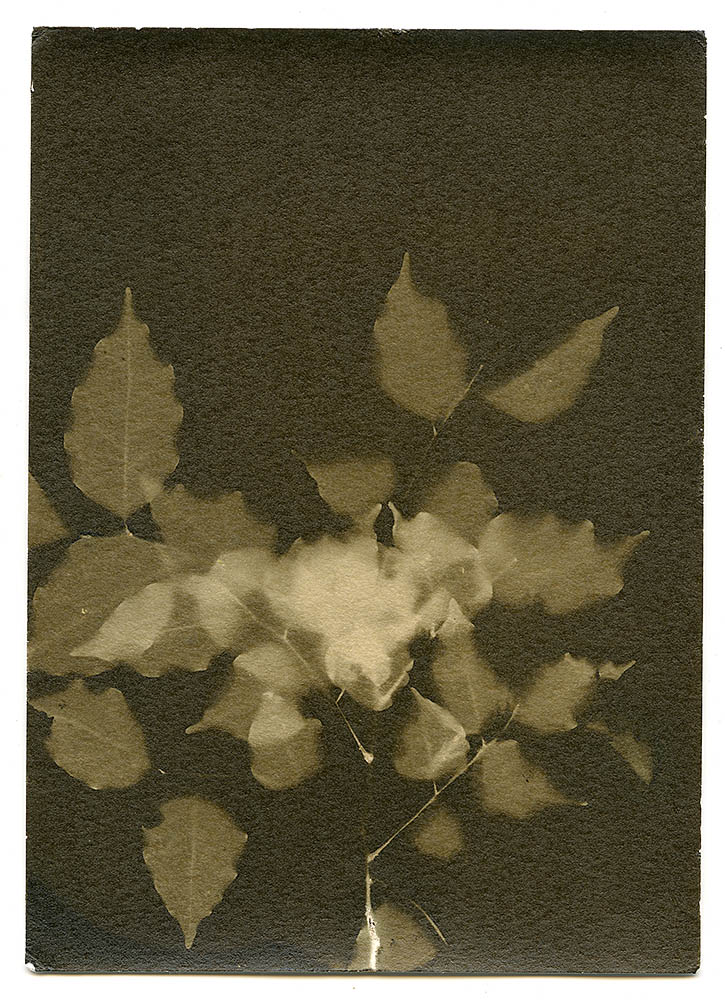

A collection of on site photographic imprints of jungle leaves makes up a herbarium that not only show what plants grow on the different elevations in the rainforest, but also gives an impression of the humidity and amount of light on site.

Photographic soil samples display signs of the even levels of humidity in the ground while river water marks show differences in water quality in the different river deltas.

All the photographs are made on site as original and unique imprints of the rainforest landscape.e

©Stig Marlon Weston, Flora Sample from Empirical. A collection of lumen prints of flora samples sorted by where they are taken from the different levels of elevation of the forest floor in the Amazon rainforest.

©Stig Marlon Weston, Microclimate fro, Empirical, A collection of lumen prints of topsoil samples made in a grid at a microclimate site on the forest floor in the Amazon rainforest.

©Stig Marlon Westomn, Soil Sample from Empirical. A collection of lumen prints of topsoil samples made at the different levels of elevation of the forest floor in the Amazon rainforest, from the water level to the platou.

©Stig Marlon Weston, Flora Sample #3 from Empirical. A lumen prints flora sample made in a scientific research nature reserve in the Amazon rainforest.

©Stig Marlon Weston, Flora Sample #1 from Empirical. A lumen prints flora sample made in a scientific research nature reserve in the Amazon rainforest.

©Stig Marlon Weston, Foliage Density #1 from Empirical. A collage of film photograms contacted printed together, showing the amount of light let through by the seemingly dense jungle foliage growing in the Amazon forest.

©Stig Marlon Weston, Tapajos, River Sample from Empirical. A lumen prints water sample made at one of the three main rivers that make up the Amazon river.

©Stig Marlon Weston, Soil Sample #13 from Empirical. A lumen prints topsoil sample made in the forest floor in the Amazon rainforest.

Stig Marlon Weston lives and works in Oslo, Norway, dividing his time between personal projects and commissioned photographic work. He studied photography in vocational college on a remote island in the north of Norway. Seduced by the magic of the darkroom, and given the opportunity to work outside of school hours, he explored ideas and invented processes he would later read about in the school library. Today he has run one of Norway’s central studio collectives for more than 20 years, also curating exhibitions and organizing photography events for the emerging photography scene in Norway. Weston exhibits broadly and has been represented at the annual national and regional exhibitions, taken part in curated group shows in Europe, the US, and Asia, and was awarded the Grand Prize in a competition at See.Me, exhibiting in NYC. The last years he has focused on doing artist residencies abroad to challenge himself into making site specific work in unfamiliar places and develop new context based processes.

Olaf Willoughby is a photographer, writer and researcher living in London, UK. His work involves everything from advocacy to collaboration with other artists. From interviewing to combining abstracts with haiku poetry.

Olaf has a life long fascination with creativity. Exploring new and different ways in which we can take our work as artists to new levels. As Robert Frost said, “No surprise for the writer, no surprise for the reader’.

His work has been; featured in UK fine art and photo magazines, exhibited in UK, US and European venues and used by The World Wildlife Fund who distributed 5,000 ebook copies of Olafs’ book, ‘Antarctica, A Sense of Place’ to help raise money for environmental causes.

His interest in storytelling also extends beyond photography. He has spoken on the art of using storytelling to improve business communications on various platforms in London, Basel, Amsterdam, Shanghai, Athens and Chicago.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Carolina Baldomá: An Elemental PracticeJanuary 5th, 2026

-

Time Travelers: Photographs from the Gayle Greenhill Collection at MOMADecember 28th, 2025

-

Suzette Dushi: Presences UnseenDecember 27th, 2025

-

Ragne Kristine Sigmond: Portraits of Painterly LightDecember 2nd, 2025